From the doldrums of 1969 to the boom times of 1973, oil reversed the fortunes of Union Street in the early 1970s and turned it into the ‘Golden Mile’.

When Union Street was built in 1817, it bankrupted Aberdeen leaving the city with a debt of £220,000.

But come 1973, £220,000 wouldn’t buy a single site on the Granite Mile.

The irony was not lost on investors who were desperate to find any foothold on Union Street and capitalise on the Seventies success.

It was Scotland’s third busiest shopping street behind Princes Street and Sauchiehall Street. Neither of those is in great shape today either.

At the time, china and glass shop owner John Whitehead said: “The bad old days of 1969 with empty properties lining Union Street are passed. We’re over the hump now.”

The only reason independent, family retailers weren’t priced out of rising rents was because most owned their premises.

It was not merely Aberdeen’s shopping mecca, but now a commodity to be bought, sold, knocked down and built up.

The traditional frontages weren’t being removed to make way for new shops, but offices.

But as we know now, when the good times are gone, the offices are left empty.

You could argue the bust was already beginning in the 1970s with the loss of the traditional buildings that gave Union Street some of its unique identity.

Join us as we take a deeper look at different aspects of Union Street during every year of the 1970s – and discover some of our contemporary complaints are nothing new….

1970: Street fighting men

On their 1970s hit Street Fighting Man, The Rolling Stones sang: “Cause summer’s here and the time is right//For fighting in the street, boy”.

While Aberdeen didn’t have notorious factions of youth gangs like other parts of the country, Saturday night was definitely alright for fighting on Union Street.

In July 1970, Union Street was in the local headlines because groups of youths were causing trouble after the dance halls closed for the night.

Aberdeen police were “keeping a close watch for trouble” among youngsters fighting in the Granite Mile after nightfall.

Embarrassingly, a group of French children staying in the city had been pre-warned to “scatter” if approached by teens on Union Street. Zut alors!

Not the PR the city’s tourism board was hoping for.

But then-Assistant Chief Constable John Nicol sought to bring reassurance.

He said: “We have always had a problem of groups of people gathering in Union Street.

“At the moment there is more trouble from them and we have special patrols at night to prevent any further outbreaks.”

In a surprising stance, he came out on the side of skinheads and said they weren’t the problem.

He added: “Just because someone wears his hair cropped short and braces over his shirt, it does not mean he causes more trouble than anyone else”.

1971: A gey scunner, did it always rain in summer?

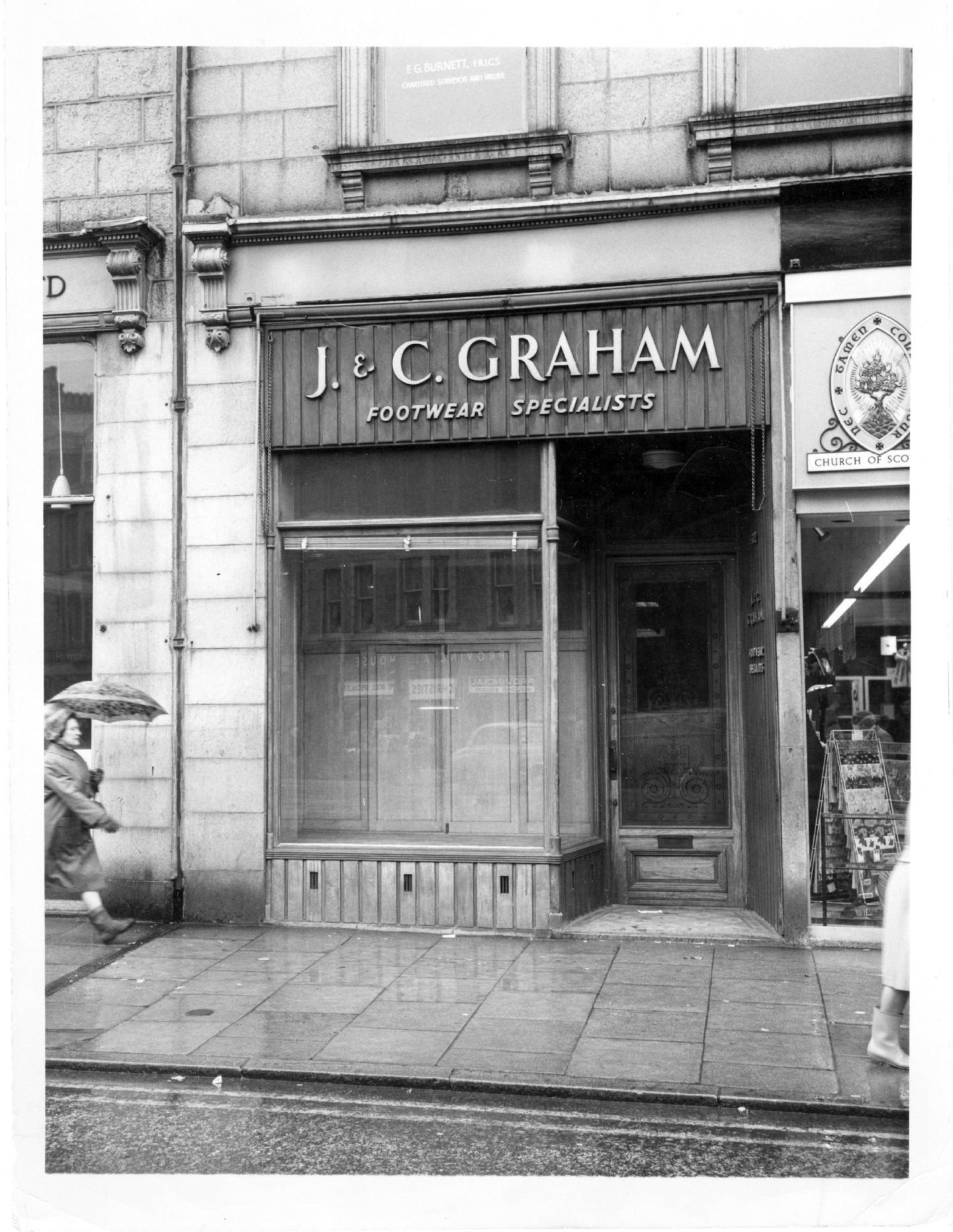

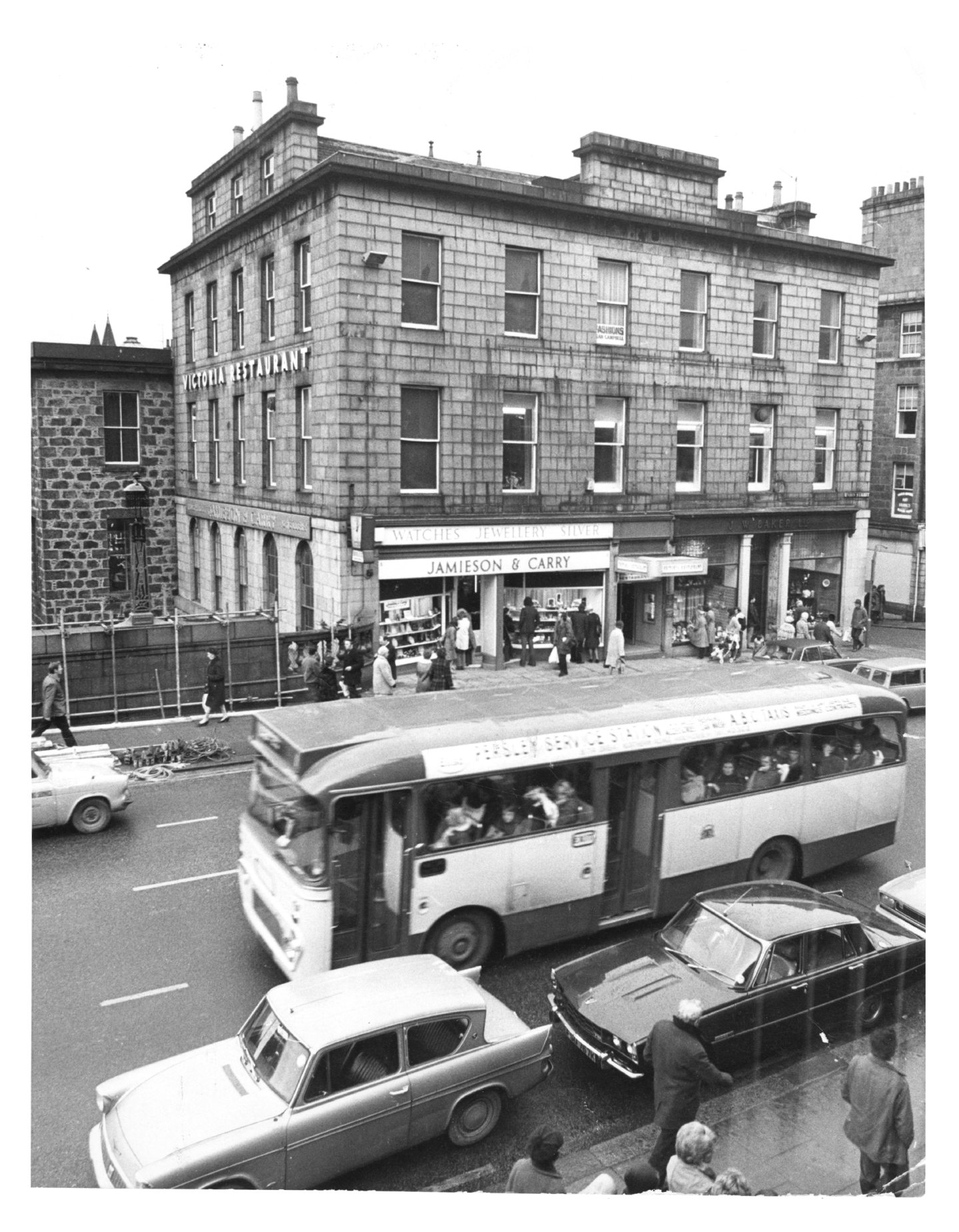

Another summer and another downpour, but who remembers these fabulous shop fronts from 1970s Aberdeen?

With our rose-tinted spectacles on, perhaps we can think of the early 1970s as Union Street’s swan song.

This was Aberdeen just before the arrival of that modern phenomenon – and the death knell of many a high street – shopping malls.

Even on the wettest days, Union Street was busy.

People could always duck into the Gloucester Hotel, the Victoria Restaurant or Littlewoods’ canteen for shelter and scran.

As well as being busy, the common theme of Aberdeen’s central thoroughfare in the 1970s is a clean street.

The unique mixture of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian architecture still dominated, with the odd 1960s block here and there.

Although old, the buildings and pavements outside them were well-kept, the period windows, signs and doors well maintained.

The only trees to be seen are those in St Nicholas Kirkyard, not poking out of chimneys.

1972: When is a building not a building?

The far end, or as some might say the top end, of Union Street has always been a little quieter than the thronging crowds between Bridge Street and Broad Street.

But our photo still shows passing trade at those little independent shops from 50 years ago.

Here you can see the opticians David Beck, the British School of Motoring at number 474 and under that fantastic old lantern was Gordon & Smith, the wedding cake maker and confectioner.

That lantern is, sadly, long gone as are all of the shops in this 1972 photo.

More recently they’ve been occupied by Everest Nepalese restaurant, Aberdeen Whisky Shop and the dry cleaners.

But what of that curious, tall building next door? Its frontage is unlike any other on Union Street.

Numbers 478-484 Union Street was not originally shops or flats, but a huge cistern called the Waterhouse.

It was effectively a gigantic, four-storey water tank disguised as a tenement.

Designed by Aberdeen architect John Smith, it dates from 1829 and was part of the expansion of the water supply scheme in the west of the city.

Two 50hp steam engines in a fountain house at Garthdee pumped water at a rate of 1000 gallons per minute to the cistern in Union Street.

In 1900 the Waterhouse was converted into the British Linen Bank, then later, shops with accommodation above. The quirky building is now category C-listed.

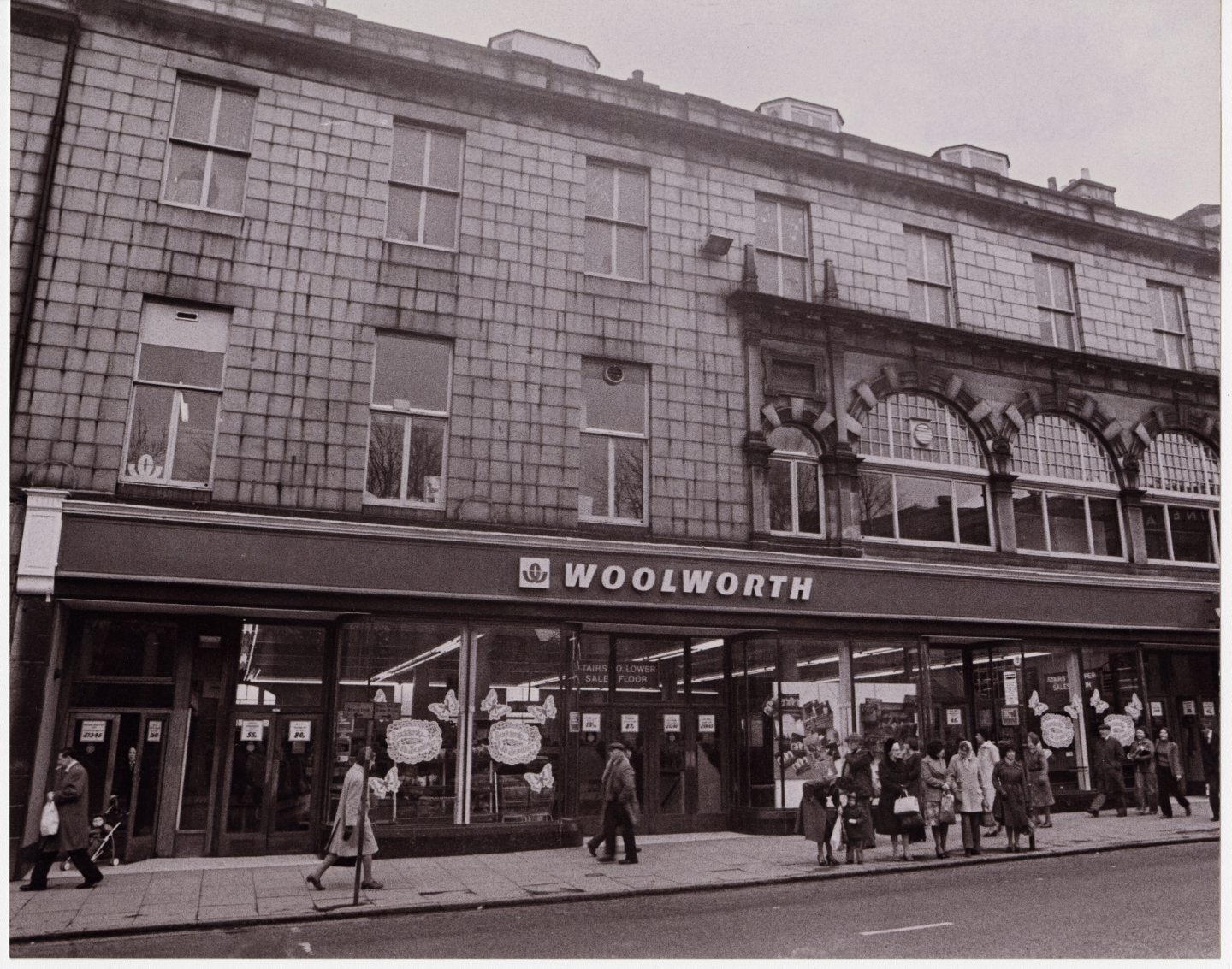

1973: From the Granite Mile to the Golden Mile

In 1973, the Press and Journal reported how Union Street, “Aberdeen’s street of enterprise”, was “in the throes of a property boom more golden than the city’s famous sands”.

The discovery of oil and the city’s new flush of wealth was ringing in the tills up and down Union Street.

And the Granite Mile was now nicknamed the Golden Mile.

Any retailer worth its salt was vying to stake a claim on Union Street, and the city’s reputation was “right up the investment ladder”.

It was said Union Street was becoming to businessmen to what Harley Street was to doctors in London. Lucrative.

It was no surprise, then, in 1973 that plans were afoot to demolish another Union Street cinema to free up real estate.

This time it was The Playhouse being targeted, along with shop premises next door belonging to James Scott & Son.

In its place, James Scott & Son wanted to create a supermarket with a lounge bar and restaurant above, and offices above that.

But three years later, the Playhouse was clinging on, the council wouldn’t allow the demolition without a guaranteed developer.

Erring on the side of heritage, Councillor Frank Magee said: “Simply, to tear down this building and wait for a developer would be disastrous.”

The Playhouse was described as “a very dignified cinema which with a thick crimson carpet which led upstairs to a delightful cafe”.

However, it was eventually flattened and now in its place stands – you guessed it – empty shops and offices, just along from the Tesco at the junction with Holburn Street.

1974: Union Street a victim of ‘ghastly society dominated by shallow values’

By 1974, the council was beginning to dig its heels in against developers.

It pushed back against wholescale demolitions, seeking to retain historic buildings like the Clydesdale Bank on the corner of Union Street and Union Row.

Ultimately that bank was swept away, along with the Majestic Cinema, and replaced with shops and offices (the office space is vacant today).

But in May ’74, the city’s planning committee announced a “get tough policy to preserve some of the unique character in Union Street”.

The council was facing a tsunami of applications to rip apart or redevelop properties.

One of Union Street’s newest buildings in 1974 was the BHS building which replaced an entrance to the old Victorian market.

Committee convener Councillor Raffan said: “We are very concerned. People think that the planning committee is half asleep, but I can assure them it’s very much the reverse.”

He explained the committee was not happy with how Union Street was looking.

The Evening Express said Aberdonians felt what was the former “showplace of Aberdeen was dying the death of a thousand cuts”.

Aberdeen Civic Society agreed, saying developers were “hovering around like vultures waiting to strike”.

Outgoing chairman of the civic society, Colin Thoms, said the changing face of Union Street in his opinion was “a sign of a pretty ghastly society dominated by shallow commercial values”.

In particular, the civic society was pushing back against the proposed demolition of 252 Union Street, the Amicable Building.

On this occasion, the council and civic society were victorious – the building still stands in all its Art Deco glory.

However, it too contains 3,532 square metres of empty office space today.

1975: ‘Howls of protest’ over old Trinity Hall demolition plans

By 1975, the Evening Express was weighing in on Aberdeen’s heritage, backing public calls to have buildings saved.

Particularly as 1975 was European Architectural Heritage Year.

Aberdonians wanted the spire at Triple Kirks, old buildings at 31-39 Don Street, and the Trinity Hall on Union Street preserved.

The historic building had been the former home of the Seven Incorporated Trades, but by 1975 was owned by Littlewoods.

Littlewoods had its shop next door and mooted plans to demolish the unique 1846 building for an extension.

However the plans were met with “howls of protest”.

Reader Joan Macleod, of Fonthill Road, told the EE she feared it would be handed over to the “sledgehammers of the property developers who have turned our main street into the sham it is today”.

Meanwhile, lecturer at the Scott Sutherland School of Architecture Dr William Brogden had organised a petition among staff and students.

He explained it was “the only Gothic building in the whole of Union Street”.

Although the old Trinity Hall wasn’t flattened in 1975, Littlewoods did get its way in 1979 and the majority of the building was demolished.

The Gothic facade was retained, now the Trinity Centre, but the internals and plaster murals painted by the city’s art students in the 1930s were lost forever.

1976: More Union Street shops becoming offices

Come 1976, retailers were also unimpressed with the changing face of Union Street.

Shopkeepers were concerned at the number of stores being allowed to be converted into office accommodation.

They felt there were too many banks and financial businesses between the Huntly Street and Chapel Street junctions alone.

When national knitwear brand Roderick Tweedie closed its Union Street premises to focus on wholesale orders, neighbouring shops were anxious.

They had seen other shops turn into offices.

Jack Leith, manager of clothes shop Caird and Son, said: “I fear that the more offices there are, the less attractive the area becomes to shoppers, and if shoppers don’t visit this part of Union Street our trade is bound to suffer.”

The council said it was facing a dilemma: while it would prefer “live shops” it couldn’t force retailers to move in.

Even the outgoing business Roderick Tweedie said it wished for the shopfront to remain retail.

All of these shops are long gone, and ironically two of them are now filled with a financial services provider and a credit union.

1977: Stark warning over future of Union Street

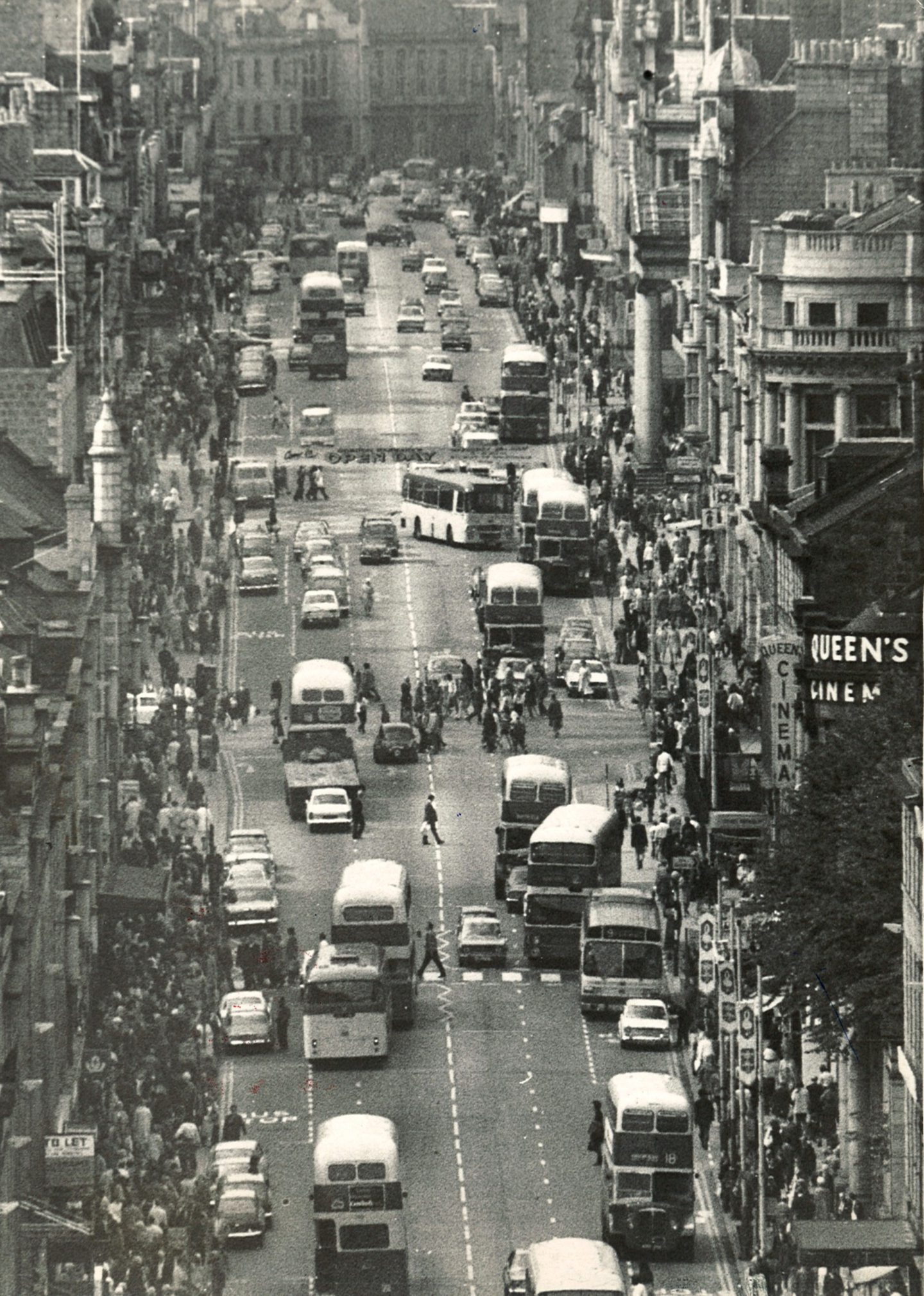

Attention turned to the road and not the buildings in 1977 when councillors looked to pedestrianise part of Union Street.

Proposals were put forward to the council to remove cars from the stretch between Bridge Street and Market Street.

Turnover in this section of Union Street alone ran into “tens of millions of pounds annually”.

It was felt such measures would enhance the shopping environment in the days when folk were practically elbow to elbow walking up busy Union Street pavements.

Councillor Norman Bonney heartily agreed saying he felt the council had been backward in the matter.

But councillors raised concerns over the cost and disruption of rerouting traffic.

Mr Clemens, a spokesman from retail consultancy firm Drivers Jonas, pointed out an emerging trend for superstores on the outskirts of towns and cities.

In addition to foodstuffs, they were stocking “durables” – household goods like electronics, clothes and furniture.

Mr Clemens said Union Street should be doing all it could to retain these shops rather than see them lost to retail parks – and part of that was improving the shopping environment.

He warned there was “a danger that Union Street would no longer be the city’s shopping centre”.

Pedestrianisation did not happen, although nearby St Nicholas Street was demolished in 1982 and turned into a pedestrian zone with a shopping mall.

Later in 1977, Littlewoods began developing the area behind its store as part of multi-million-pound expansion.

1978: ‘The biggest shopping development ever’

Early in 1978, details emerged of phase two – “a luxury shopping mall and car park development” for Union Street.

The complex would be built over disused railway lines at Aberdeen Railway Station below adjacent to the Inverness-Aberdeen line.

The mall was to have 27 shop units and parking for 240 cars.

And crucially, the development would come as no cost to the council.

By March, the plans were approved in principle for what was billed as “the biggest shopping development ever for Aberdeen”.

However, the old Trinity Hall would largely be demolished to facilitate the development, although the frontage would be retained.

At that time, it was also proposed that in the future a covered walkway would be built under Guild Street, directly linking the railway and bus stations to Union Street.

Access would also be gained to the mall through Littlewoods (now Primark) and C&As (now the Travelodge).

Aberdeen Chamber of Commerce wanted 1500 parking spaces; members were concerned over the influx of cars to the city centre.

When the plans came to fruition the following year, a 400-berth car park had been agreed with 26 shops.

1979: Offices on Union Street stagnated during recession

At the end of 1979, work began on creating the ambitious five-storey building with a projected opening date of 1983.

Initially, it was to be called the ‘Atholl Centre’ after the property developers Atholl Investments.

The vast site was bounded by Union Street, College Street and Bridge Street.

A large portion of the work was ground surveys at railway level – as well as demolishing Trinity Hall.

But within months of work beginning, a severe economic recession hit the UK.

It was considered the worst since the Second World War, until 2007.

And there were already concerns about the property market in Aberdeen.

The additional proposed 183,000 square feet of retail space at the Trinity Mall was arriving while national retailer House of Fraser shut two of its three Aberdeen stores.

David Young, senior partner at commercial property agent FG Burnett, said although the oil industry cushioned Aberdeen slightly, the property market showed the recession was “biting hard”.

Office properties which had been so in demand were now stagnating on the market.

But it was hoped that when the market did regenerate vacant offices in the West End would be populated again.

Mr Young said: “The west end of Union Street has seen less dramatic rental growth in recent years and a number of existing retail traders have closed.

“These have gradually been replaced by non-retail users such as banks, building societies and specialist retailers.”

He added that pattern of retailing was likely to change for the foreseeable future in Aberdeen.

And he was not wrong. Union Street continued to be Aberdeen’s main shopping thoroughfare until the ’90s, but in reality, one could argue the rot set in in the 1970s.

More Past Times stories

Gallery: A short history of Cults Academy, Aberdeen’s high-achieving school, in 110 photos

Lost Aberdeen: Did St Nicholas Street demolition ‘break the heart of the Granite City?’

Photo gallery: Flagship Marks & Spencer has been at the heart of Aberdeen for 80 years

Conversation