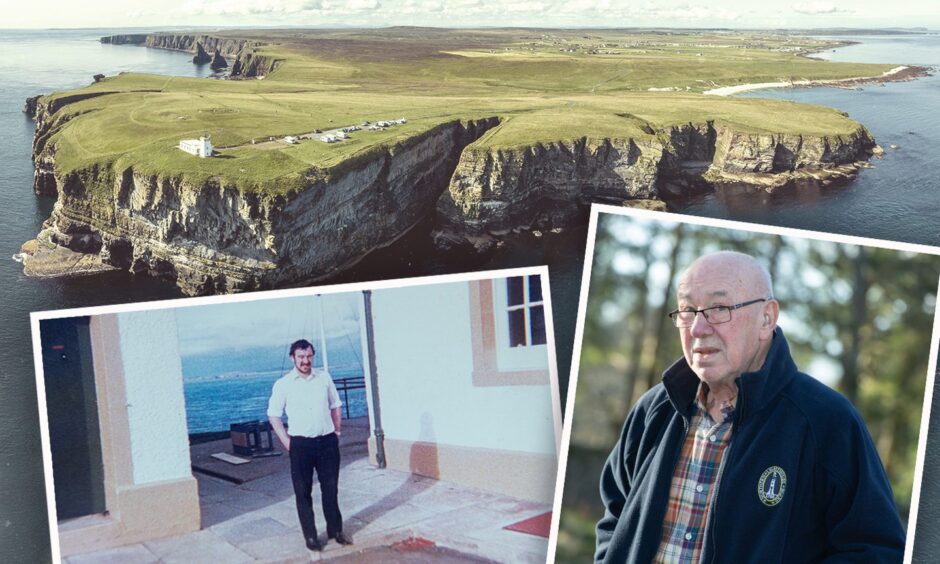

Duncansby Head lighthouse is situated on the most north-easterly headland in the UK, commanding some of the country’s most dangerous waters.

Many a ship has foundered there, caught up in the confluence of currents colliding from the Pentland Firth and North Sea with the Atlantic in the south.

The Stevenson lighthouse on the remote headland turns 100 tomorrow, amid days of community celebrations.

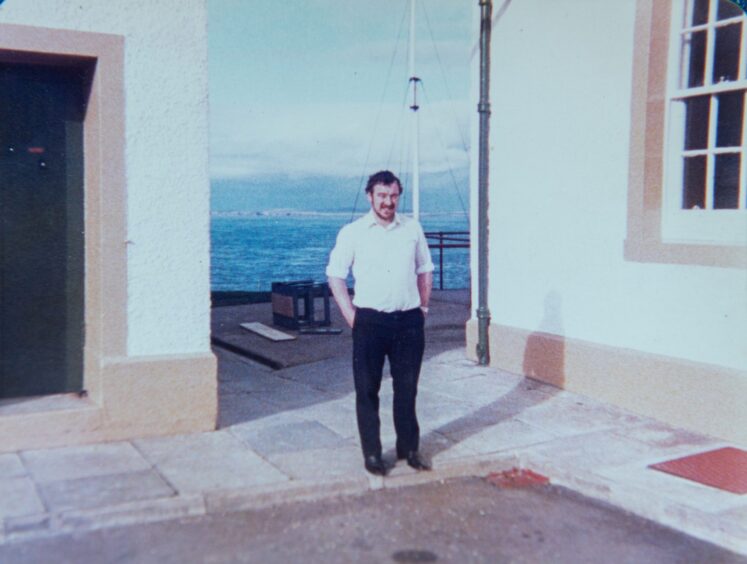

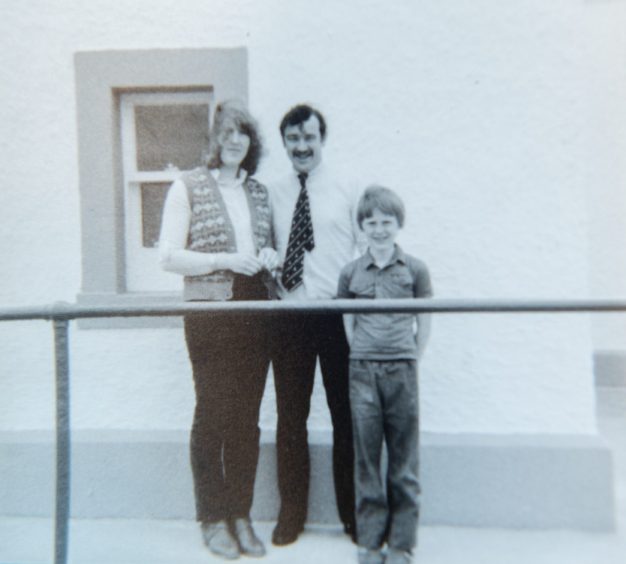

Retired lighthouse keeper Ian Duff spent five windy years at Duncansby Head with his wife and young son, from 1980 to 1985.

It may be remote, but Duncansby Head lighthouse station was as busy as it got, Ian says.

“It was classed as a control station.

“We had radio communication with the rock lighthouses in the Orkney islands, Stroma, Pentland Skerries, Suleskerry, Copinsay and North Ronaldsay.

“We spoke to them three times a day to check they were all right.

“Any problems they had, they relayed them to us, and we phoned Edinburgh headquarters on their behalf as they had no direct communications.

“They put in their grocery orders to Thurso or Stromness through us, so we acted like a mini telephone exchange.”

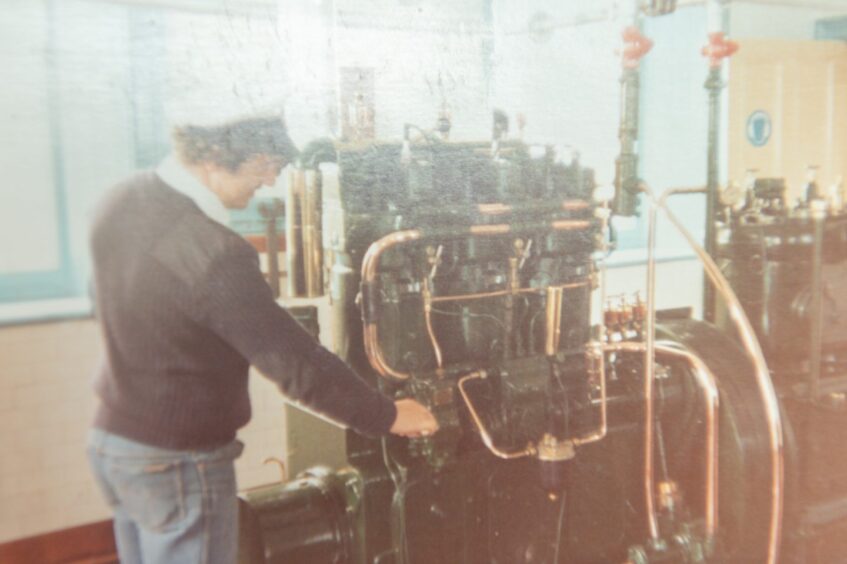

The keepers—there were four full-timers at the time—had to wind the lens machine every two hours.

The fog horn was demanding

They were also kept busy working the fog horn.

This was powered by three engines, two at a time, making the compressed air for the signal.

In winter, the water required for the process would freeze, meaning the engines had to run 24/7 at a low speed, requiring constant monitoring by the busy keepers.

A busy site

There were plenty of people on site at that time too, what with the keepers’ families, a manned look out post and the Royal Observer Corps bunker nearby.

Ian said: “It was so windy. I can only recall seeing my wife sitting outside for a cup of tea with the other wives once or twice during our time there.

“In those days we had garages, and I remember in one storm remembering that my garage door wouldn’t shut properly.

The wind could be terrifying

“I was afraid the wind would get in and lift not just my roof off but the whole lot and send the garages over the cliff.

“My wife and I tried to drive wedges in the door and on the way back we were both picked up clean off our feet and thrown against a wall.

“We ended up laughing from fright.”

Power cuts were a bit of a nightmare at Duncansby Head lighthouse.

“We had a standby generator for light in the houses,” Ian said, “but we had to share the standby gas cooker.

“The senior keeper would go first, followed by the second senior and so on.”

Sunday nights would be particularly hectic at the lighthouse.

“Calls would come in from the fishing boats thinking of heading through the Pentland Firth to see what the weather was like. We acted as look-out.”

At least there weren’t too many stairs…

The low, square design of the lighthouse was something of a blessing for the keepers at Duncansby Head.

It only took them 30 seconds to shin up the three ladders to the light room, whereas in Ian’s next posting at Pladda lighthouse off Arran he had to allow an extra five minutes to climb 120 steps every time he went up.

Lighthouse not built until 1924, despite vital position

It seems extraordinary that in such a commanding position Duncansby Head lighthouse wasn’t built until 1924.

There wasn’t even a rush to build it after an inquiry in 1911 in the House of Commons deploring the loss of so many shipping casualties in the Pentland Firth.

A suggestion that it might be to do with insufficient lighting at Duncansby Head was dismissed, and the Northern Lighthouse Board at the time said they had never been approached about a light at Duncansby Head.

Duncansby was not a priority

They had more important priorities for their funds, they said.

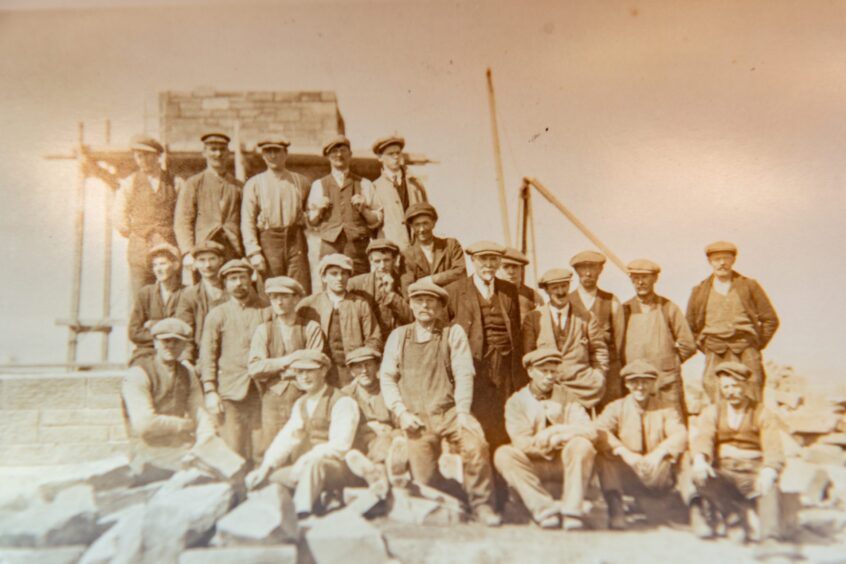

But something gave, and by 1921 tenders were invited for the construction of ‘Duncansby Head Fog Signal Station’.

There were to be a small tower, three dwelling houses, an engine room and store houses.

The task fell to David Alan Stevenson from the famous Stevenson family of lighthouse engineers.

He was grandson of the founder of the dynasty, Robert Stevenson, and cousin to the author Robert Louis Stevenson. His brother Charles and uncle Thomas were also lighthouse engineers.

First to be attacked during the war

Duncansby Head was the first lighthouse to be attacked in the Second World War.

On April 6 1940, a Nazi plane strafed the lighthouse with bullets, but fortunately no-one was injured.

The plane hurtled on to attack Stroma lighthouse, three and a half miles to the north-west of Duncansby Head.

Again the rattle of bullets was heard, but no-one was injured.

Message home from the high seas

There was also the charming tale in 1948 of how the principal keeper James Campbell’s son sent as message home as he was passing.

Robert Campbell was aboard Narva, bound for Gothenburg from Belfast.

When he caught a glimpse of home over a mile away, he semaphored a brief greeting to his folks.

James picked up the message through a telescope.

It must have been a touching moment, given the lack of means of communication, compared to now.

Automation eventually reached Duncansby Head

The costs of manning lighthouses had led the Northern Lighthouse Board to investigate automation from as early as 1894.

A big push came in 1960-1980, installing gas-operated lights in 25 lighthouses.

Further technological advances saw the remaining 65 lighthouses automated between 1980 and 1998, Duncansby Head in 1997 being one of the last.

The very last lighthouse to be automated was Fair Isle South, in 1998.

More articles on lighthouses:

12 spectacular lighthouses across the north and north-east – from Covesea to Dunnet Head

The modern-day lighthouse keepers safeguarding Scotland’s seas, from Shetland to Aberdeen

Conversation