Schools were dotted across Aberdeen City Centre during the densely-populated Victorian era, but nowadays, there’s hardly a trace of many of them left — unless you know where to look.

Prior to the Education (Scotland) Act 1872, attending school was largely voluntary and they were often parish schools run by churches.

But when legislation made education compulsory up to the age of 13 in 1872, more schools were built in Aberdeen to cope with the increasing rolls.

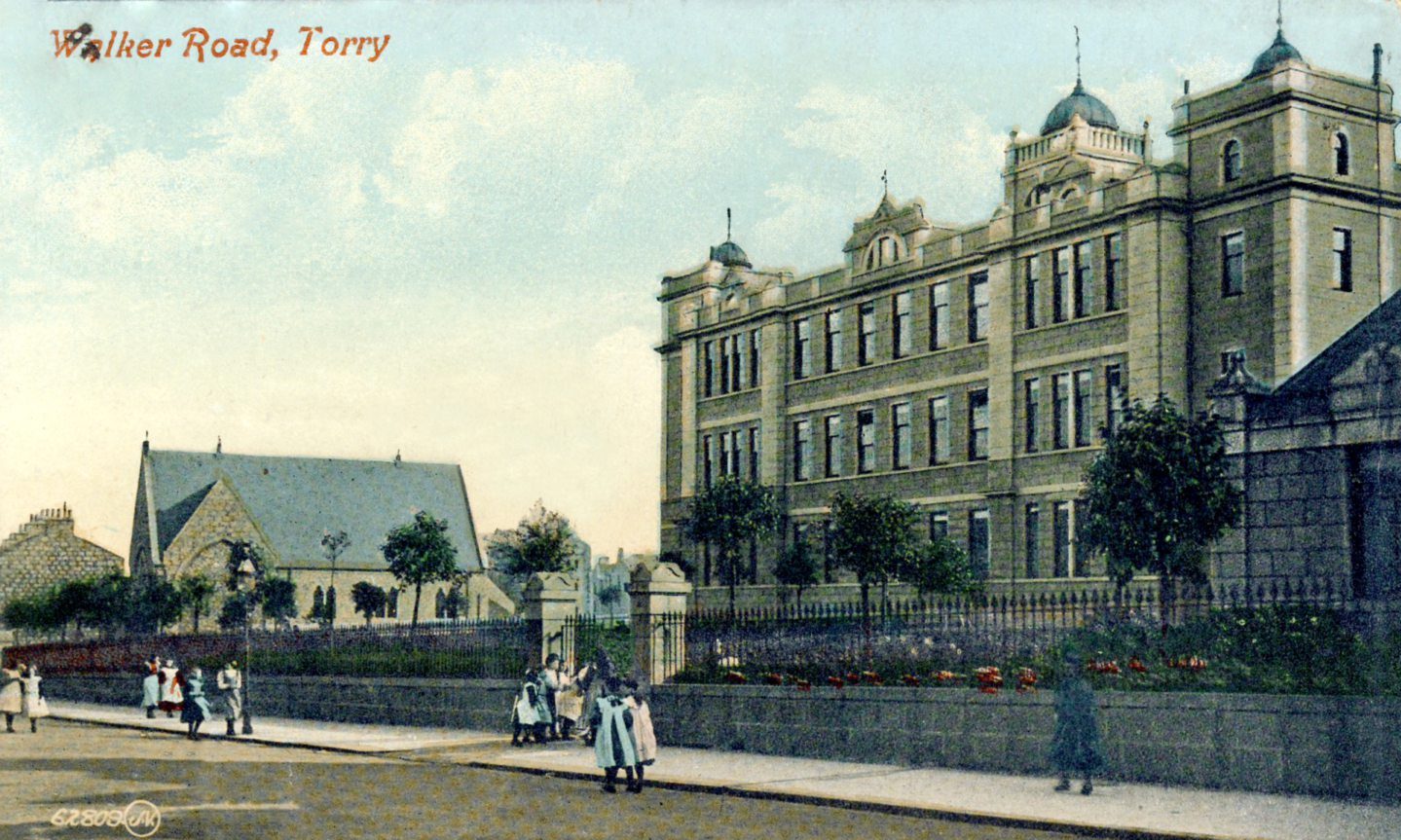

A remarkable programme of school infrastructure at that time produced some of the city’s most attractive Victorian buildings, like Broomhill, Walker Road School and Causewayend.

All still standing (if not still inhabited in the case of Walker Road), these schools were built to last, no expense was spared.

The city’s education board was not only investing in buildings, but its future citizens.

The school board had its own master architect, John Alexander Ogg Allan, who designed much of Aberdeen’s school estate around the turn of the last century.

Some of these historic Aberdeen schools outlived the changing curricula and exam systems over the last 150 years.

But many more are long-gone, only remembered through memories and the nameless faces peering out of historic class photos.

Join us as we go through the archives to find out about these long-lost schools, what life was like at them, and their ultimate fates…

1. St Clement Street School, nestled among Aberdeen’s shipyards

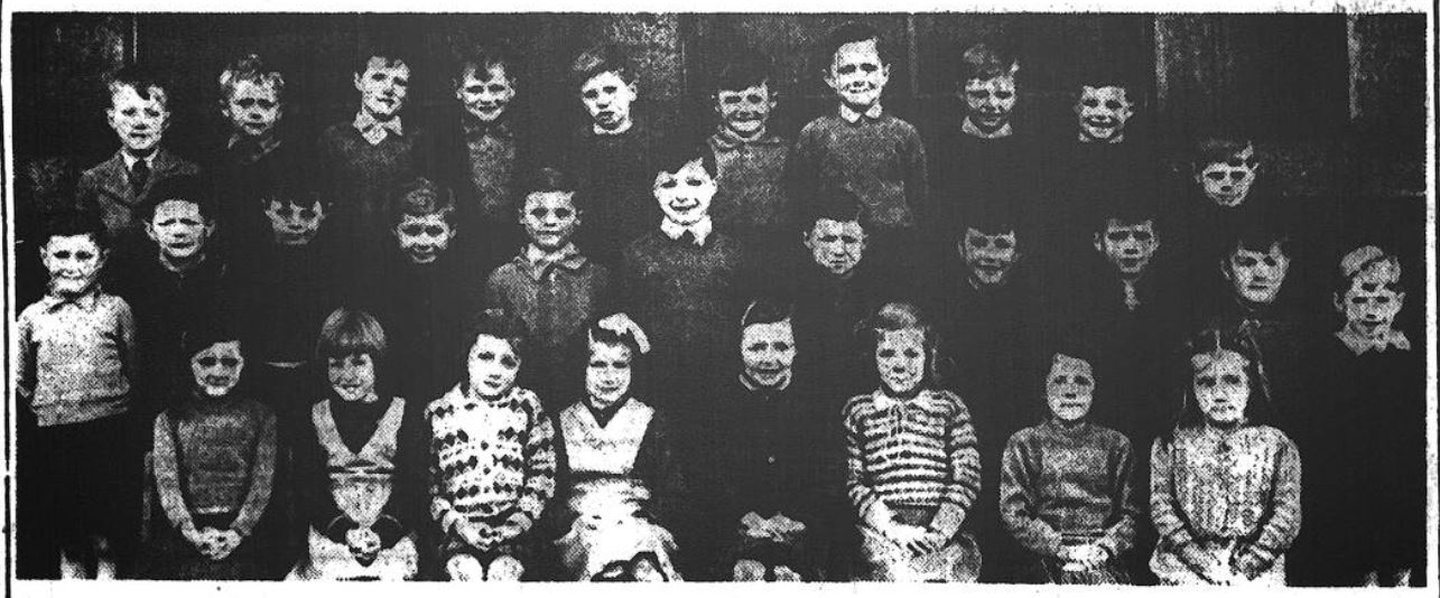

These cheery souls were pupils at St Clement Street School in Fittie in 1957, but the following year the school would close forever.

The original school was Footdee Public School, a small building which opened circa 1870.

One of Aberdeen’s east end schools, nestled among shipyards, it was considered to be among the poorest. Appeals were regularly made for food and clothes.

But with many pupils coming from a sea-faring background, one remarkable tale recalled how pupils manned the Fittie lifeboat to save a stricken trawler one stormy night.

Headmaster Mr Ogilvie was so proud of the boys’ bravery a model lifeboat was made with their names around it. The model was displayed in the school for many years.

In 1874, Aberdeen School Board took over the school and renamed it St Clement Street School.

By the turn of the century it was bursting at the seams and a new building was proposed.

Aberdeen school board’s master architect John Alexander Ogg Allan designed the new purpose-built school.

The Press and Journal described how Mr Allan had “admirably” taken care “to utilise the space to the greatest possible advantage for the benefit of the scholars and the convenience of the teachers”.

Opening in March 1906, St Clement Street School was a one-class-per-standard structure – effectively one class per year group.

It could accommodate 600 pupils with 195 spaces for infants, and 405 for junior and senior scholars.

This was when no expense was spared – classrooms were spacious and the layout was well thought out.

The total cost of the building, including furnishings, was about £7500 (approximately £755,000 in today’s money).

Classrooms were arranged around a 37ft-square central hall on the ground floor.

The entrance to the three infant classrooms was from the playground, while the infants’ headmistress’s office was next to the main entrance.

A further two classrooms for younger scholars completed the ground-floor along with headmaster Mr Lothian’s office, painted in “deep crimson”.

There were separate boys’ and girls’ stairs leading to the first floor where there was five classrooms, a cookery room and scullery, a technical workshop and woodstore, and a library.

The central hall rose up through both storeys of the building with a gallery around the first floor.

The P&J reported how “on entering the school, the visitor finds himself in the spacious hall, abundantly lit from the roof during the day and pendant electric lights in the evening”.

In a forward-thinking decision, there was a sliding glass partition in one of the infants’ rooms allowing more or less space depending on the lesson.

The interior was typically Edwardian. Woodwork was stained pine and walls were shades of green, complemented by cream and white glazed tile dados.

The school excelled in music, regularly receiving praise and prizes for its choir, which competed annually in Aberdeen’s Music Festival.

Later, in 1923, St Clement School amalgamated with nearby York Street School, with the infants transferring to the York Street premises.

But as far as Aberdeen’s schools go, the new St Clement Street School’s existence was fairly short.

Just 52 years after the celebrated building opened, the education board reluctantly closed it for good.

The school roll fell as the Fittie population shrank, but the board was divided, voting just 13 to 12 in favour of closure.

Lieutenant Colonel Butchart led the opposition, arguing the large classrooms with smaller classes would improve education.

He was overruled, and pupils transferred to nearby Hanover Street School.

The school sat empty for nearly 20 years, targeted by vandals and thieves, before it was demolished along with neighbouring tenements in the late 1970s.

2. Holburn Street School, where pupils cheered when it burned down

Holburn Street School was originally Ross’s School when it opened on October 14 1864.

It was one of Aberdeen’s old parish schools, before it was taken over by Aberdeen School Board in 1890.

As well as educating pupils during the day, it was also used for evening classes in the Holburn district.

The old school building was modernised and extended in 1911 to cope with increasing numbers of pupils.

There were complaints that Ferryhill School was practically being used as an annexe for Holburn Street.

School board architect Mr Allan designed a new classroom block, as well as a central hall and gymnasium, which would serve both buildings.

There were five infants’ classrooms to accommodate 50 pupils each, with a further 12 classrooms for junior and senior pupils accommodating up to 60 pupils each.

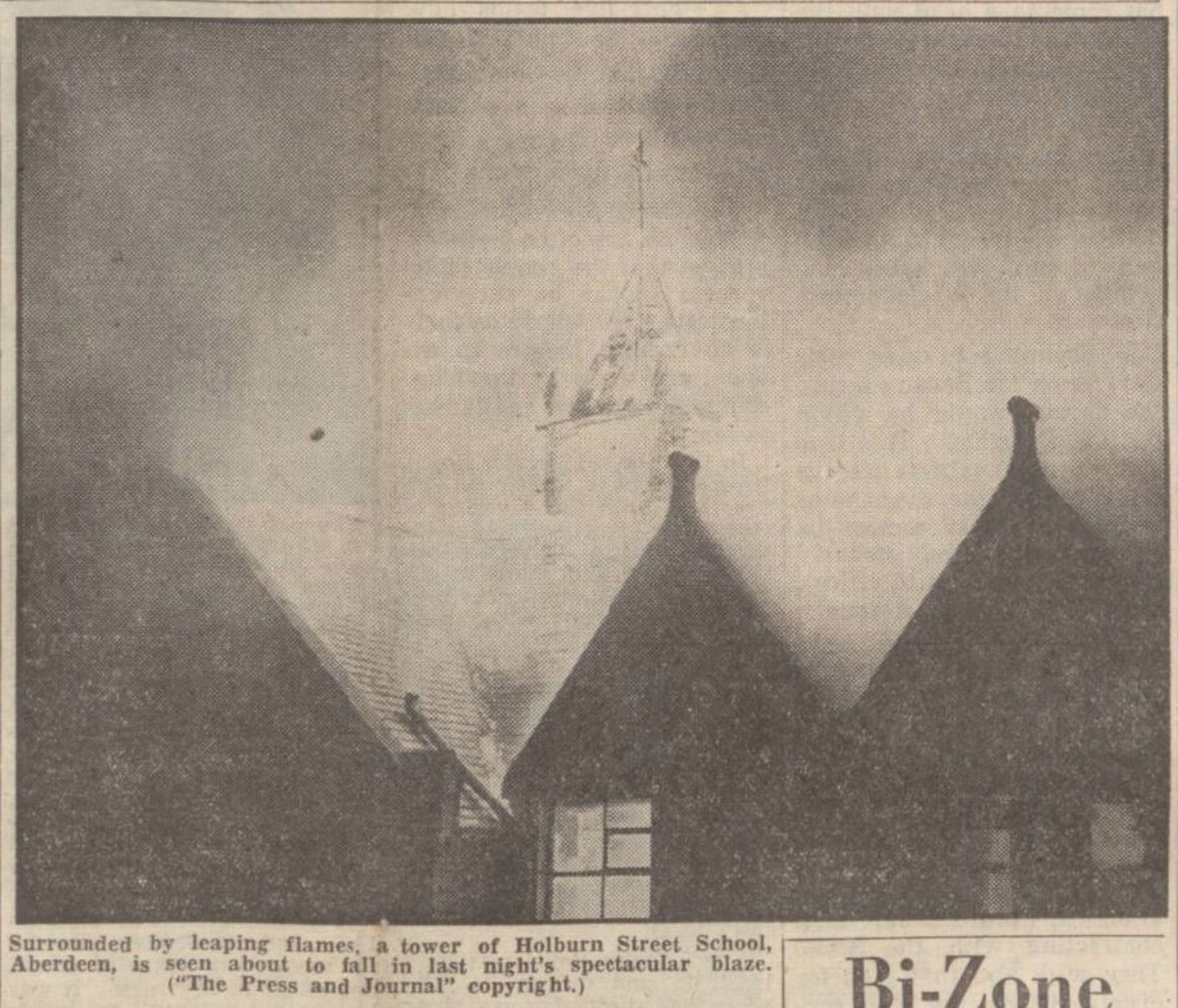

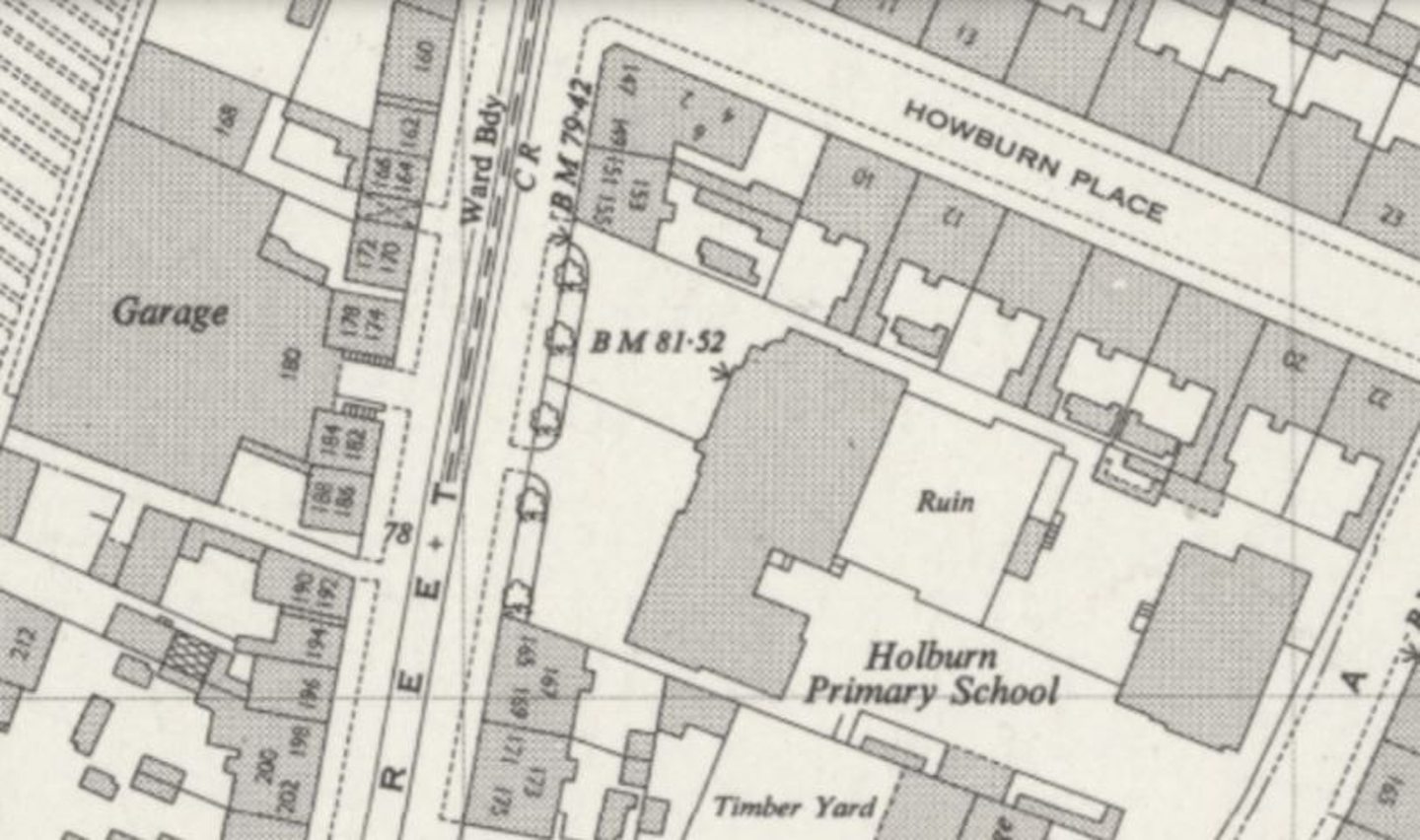

Disaster struck on January 9 1947, however, when the old part of the school went up in flames.

A mysterious explosion took place just an hour before evening classes were supposed to start.

It was described as one of Aberdeen’s “most spectacular fires in recent years”.

While neighbours in nearby Howburn Place said their house rocked “as it used to do when the bombs fell”.

The fire gutted the old eight-classroom two-storey block, and “tongues of fire and clouds of burning embers shot 60ft above the school”.

The inferno engulfed the roof and three of the four ornamental towers came crashing down in succession.

Firefighters fought the blaze from the roof of the newer school, saving the 1911 extension.

Pupils were among the thousands of spectators, and chanted in chorus “let her burn, let her burn”, punctuated with cheers at the prospect of extra school holidays.

Their prayers were answered as director of education Frank Scorgie announced the school would be closed until further notice.

But much to pupils’ disappointment, lessons commenced again from the following Wednesday in the undamaged modern block.

Within six weeks of the fire, plans were drawn up for its reconstruction, but it never happened. Another 10 years and the school would be closed for good.

Holburn Street was one of many city schools highlighted in 1953 as being “half empty” and “utilising teachers” that could have been used elsewhere.

It had capacity for 560 pupils, but ‘only’ had 324.

Headmaster Mr Roberston had been in the post just three weeks when it was announced in November 1958 that the school would close the following year.

Pupils living east of Holburn Street School would transfer to Ferryhill, while those living west would go to Broomhill.

It closed on July 3 1959 and was demolished in 1963. The site was then used for the ill-fated college of Commerce building.

The building was declared unsafe less than 20 years later and became a blot on the landscape until it was also demolished.

Talisman House now occupies the site, the only remnant of the school is the old playground wall.

3. The Middle School, where Aberdonians learned to swim

Generations of Aberdonians learned to swim at the Middle School ‘pond’ in the city centre, in the shadow of Marischal College.

The large school opened on November 19 1877 on the corner of Gallowgate and Littlejohn Street, opposite one of Aberdeen’s most historic education institutions.

Long before shopping malls and the college, the area was densely populated.

Although there was no shortage of schools in the vicinity, many were overcrowded.

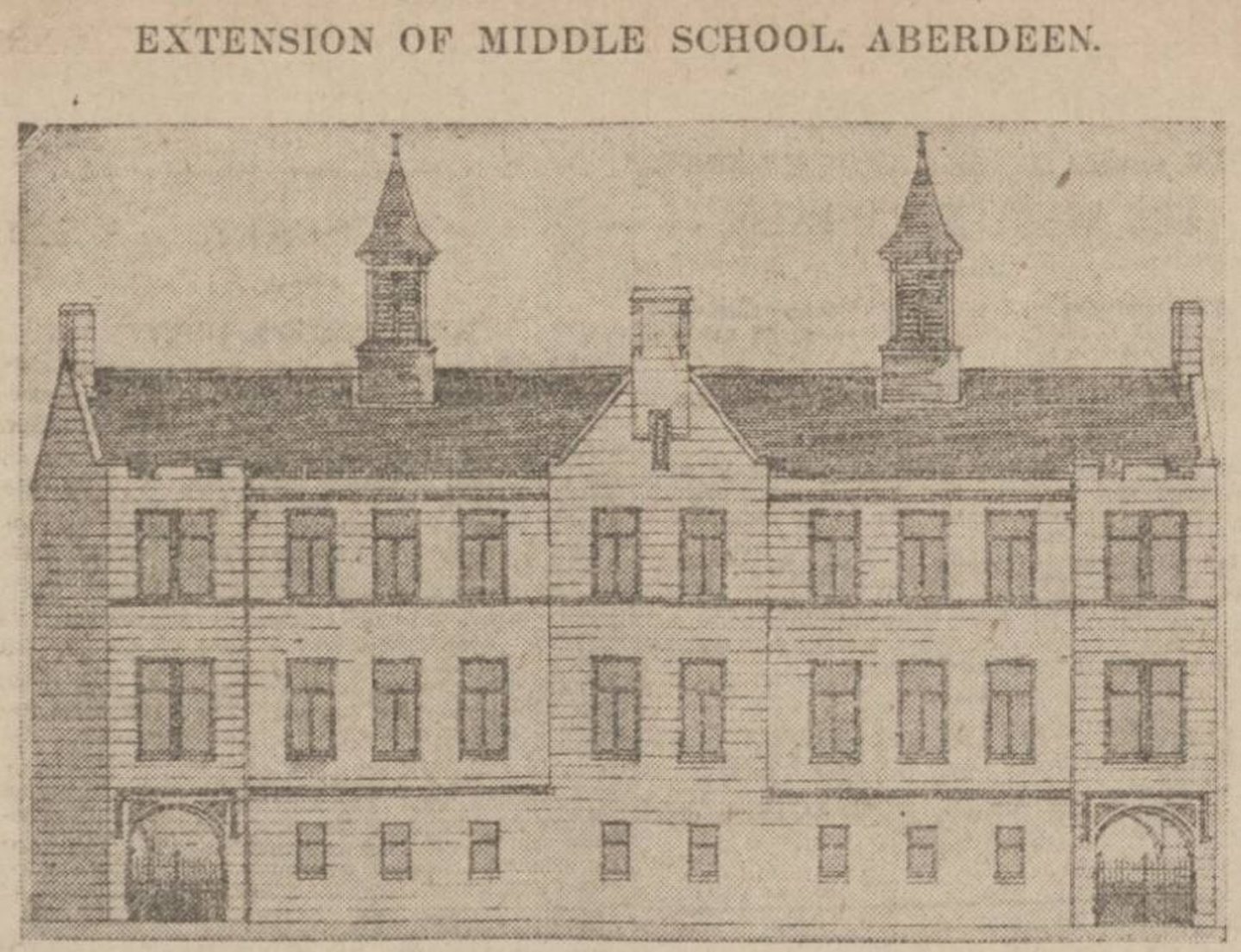

The Middle’s opening roll was 597, but by 1890 the school needed to expand again.

The new block housed cookery, laundry and manual instruction (technical) departments on the top floor, a huge gymnasium on the middle floor, and a large swimming pool in the basement.

A fairly modern concept for the late 1880s, neighbouring schools – St Paul Street and Porthill – were also to benefit from the extracurricular facilities.

Again, school board architect Mr Allan stepped up to design a building that he felt would be sympathetic to the grand Marischal College next door.

The Middle was in the city’s poverty-stricken east end. Even in 1909, headmasters made pleas for basic clothing for “bairns in the poorer districts”.

The most seriously affected schools where “distressed pupils” attended were Porthill, the Middle, St Paul Street, Frederick Street and Hanover Street.

An appeal in the Evening Express resulted in six pairs of boots and stockings being sent in anonymously.

While the Ladies Clothing Association donated 43 pairs of boots, but headteacher Mr Barnett said he had 200 applicants, meaning 157 bairns were disappointed.

He said: ” Some of the very worst of the cases are not seen, as the children are unable to attend school owing to want of boots and clothing.”

On his list of absentees, opposite many of the names sadly read “no boots”, while others “shuffled to school in their mother’s boots”.

The curriculum at the Middle in the early years was fairly innovative and reflected the poverty around it.

Aberdeen school board was particularly interested in the welfare of female, working class pupils.

It was felt cookery lessons were too extravagant and featured lavish ingredients.

An experiment was launched in 1910 when a housewifery flat was opened, where girls learned “practical housewifery based on the principle of a model home for a workingman”.

Girls took charge of the model home, learning skills like running a household, along with “all the other hundred and one things that usually fall to the lot of the ordinary working man’s wife”.

In 1924, the school became an intermediate for children aged 12 to 14 only, and a further extension in 1958 saw the addition of science rooms.

Later in the 1960s and ’70s, domestic skills were still as important as the three Rs at the Middle.

The school hosted an annual ‘parentcraft’ exhibition, attended by thousands of pupils across Aberdeen.

In 1972, Hazlehead rector Alexander Goldie said: “The task of bringing up baby should not just be the responsibility of the mother in a family, but shared by the father.”

The forward-thinking exhibition entitled ‘Living and Knowing’ taught teens about everything from hygiene, to community service and bringing up baby.

Middle School closed in 1975 when it was replaced by Linksfield Academy.

It was at the centre of planning wrangles in the 1980s, being bought and sold several times when planning applications failed.

The Middle was finally demolished in the 1990s, and the site was extensively excavated by archaeologists who unearthed 12th Century boots, before housing was built on the site.

4. The Central School (Aberdeen Academy), requisitioned in wartime

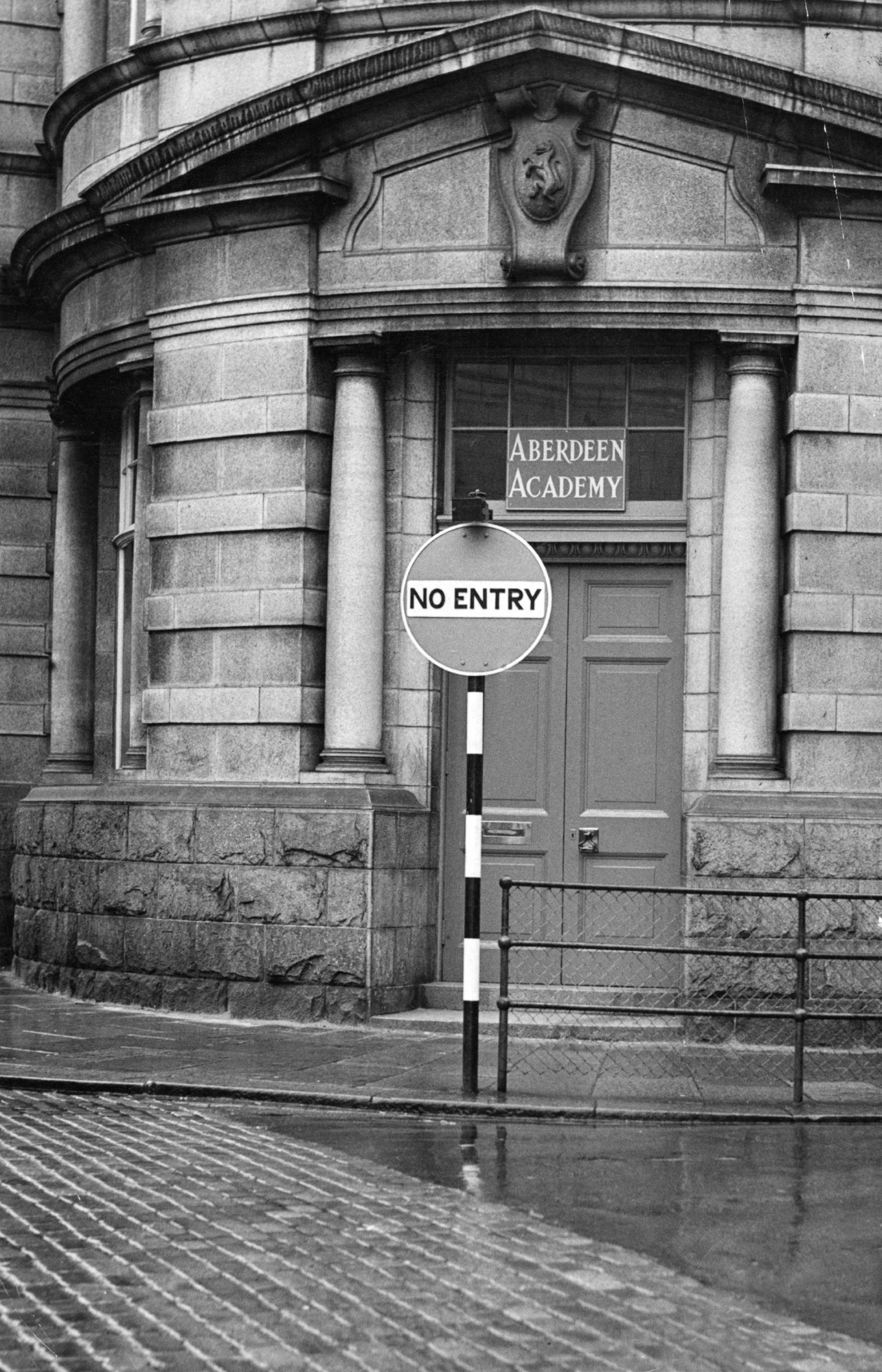

The old Central School on the corner of Belmont Street and Schoolhill is one of the city centre’s most striking buildings.

Although its been decades since anybody sat in classrooms there, its name lives on in the nearby Academy Shopping Centre.

The original Central School opened in 1894 on Little Belmont Street, now The Old Schoolhouse pub.

In 1901, the school board decided to build a higher grade school on the corner of Belmont Street and Schoolhill.

It was designed by their architect Mr Allan in the renaissance style, to complement the art gallery and nearby Robert Gordon’s College.

Opened in 1905, the new Central Higher Grade Public School linked to the old school via a corridor, and could accommodate 600 pupils.

Great care was taken in the design. The space underneath the dome was to be a museum, while every classroom was designed to maximalise natural light.

Vast classrooms were generously proportioned with ceiling 14ft high.

Art and science rooms faced the north light of Schoolhill, while the first floor had 11 classrooms for ordinary lessons each accommodating 40 pupils.

The corridors and stairwells had beautiful, Edwardian tiled dados while railed galleries encircled the tower.

It catered for pupils aged 12-15 from the city’s elementary schools and opened with a roll of around 1000.

But when the First World War broke out, the school was one of several in the city requisitioned for the war effort.

It became The Central Military Hospital as part of the 1st Scottish General Hospital, providing beds for 34 officers and 1,385 other ranks.

After the war, it returned to schooling and the town council took ownership of the Central School in 1929.

When the Second World War broke out, the Central School once again stepped up to for war service.

This time, it was taken over by public health authorities in 1939 for the sick and poor, when the military took over Oldmill Hospital (Woodend).

It was a controversial decision at the time, forcing the Central School to shared premises with Aberdeen Grammar.

By 1943, the council and health authority came to an agreement to have the sick moved to the old infirmary, and the poor to institutions in Dundee and Perth.

Firmly back in the business of education, the Central School was renamed ‘Aberdeen Academy’ in 1954 and its intake changed to pupils who passed their 11+ exams.

New school buildings were opened in 1970 and became Hazlehead Academy.

But the old Central School was still used for many years for some classes by Torry Academy pupils, then as an educational resources centre.

In recent years, the school has been part of the Academy Shopping Centre, utilised by Jack Wills, and now it is James Dun Salon.

5. Ruthrieston School, the pioneering secondary school

The original Ruthrieston School was a church school run from a small house on Holburn Street.

It was replaced by a purpose-built school in 1875 – the building still stands today, virtually unchanged, as Ruthrieston Community Centre.

Ruthrieston Public School could accommodate 180 scholars across two classrooms and a schoolroom.

Aberdeen School Board took on the school 10 years later, amid acute overcrowding in the district’s schools.

When Broomhill School opened in 1895, it was surrounded by open countryside and critics ridiculed the council saying it would never be filled.

But within five years, Broomhill was overcrowded, having also taken pupils from the old Ruthrieston School.

Meanwhile, neighbouring Holburn Street, Marywell Street and St John’s schools were also considered inadequate.

By 1902, the situation was critical, with some Broomhill pupils redistributed to Ferryhill.

The following year, a site by the River Dee was earmarked, but it was 1905 before architects even put pen to paper.

Again, Mr Allan stepped up to design the building.

After waiting for six years, the “handsome” buildings of Ruthrieston School opened on June 20 1908.

A Union Jack was unfurled on a flagstaff which had been sent to Ruthrieston by children of Aberdeen in New South Wales, Australia.

The “bright, airy and attractive” building on a large plot between Holburn Street and Riverside Drive cost £17,500, and could accommodate 1138 pupils.

The ground floor was occupied by an assembly hall, and the infants’ gymnasium and classrooms.

On the floor above there was a similar gym for junior and senior scholars, and classrooms above that.

Cloakrooms, technical rooms, cookery and laundry rooms were also on the ground floor, which the school board chairman said “should be particularly interesting to mothers”.

Holburn district schools underwent changes in 1922, and after the summer holidays Ruthrieston became an intermediate school.

It was effectively a junior secondary and considered such a success the model was adopted at schools across the city.

A pioneering institution, it was the first school solely for post-primary pupils at the time.

By 1939 the school roll was healthy and an extension was proposed, although it wasn’t constructed until after the war.

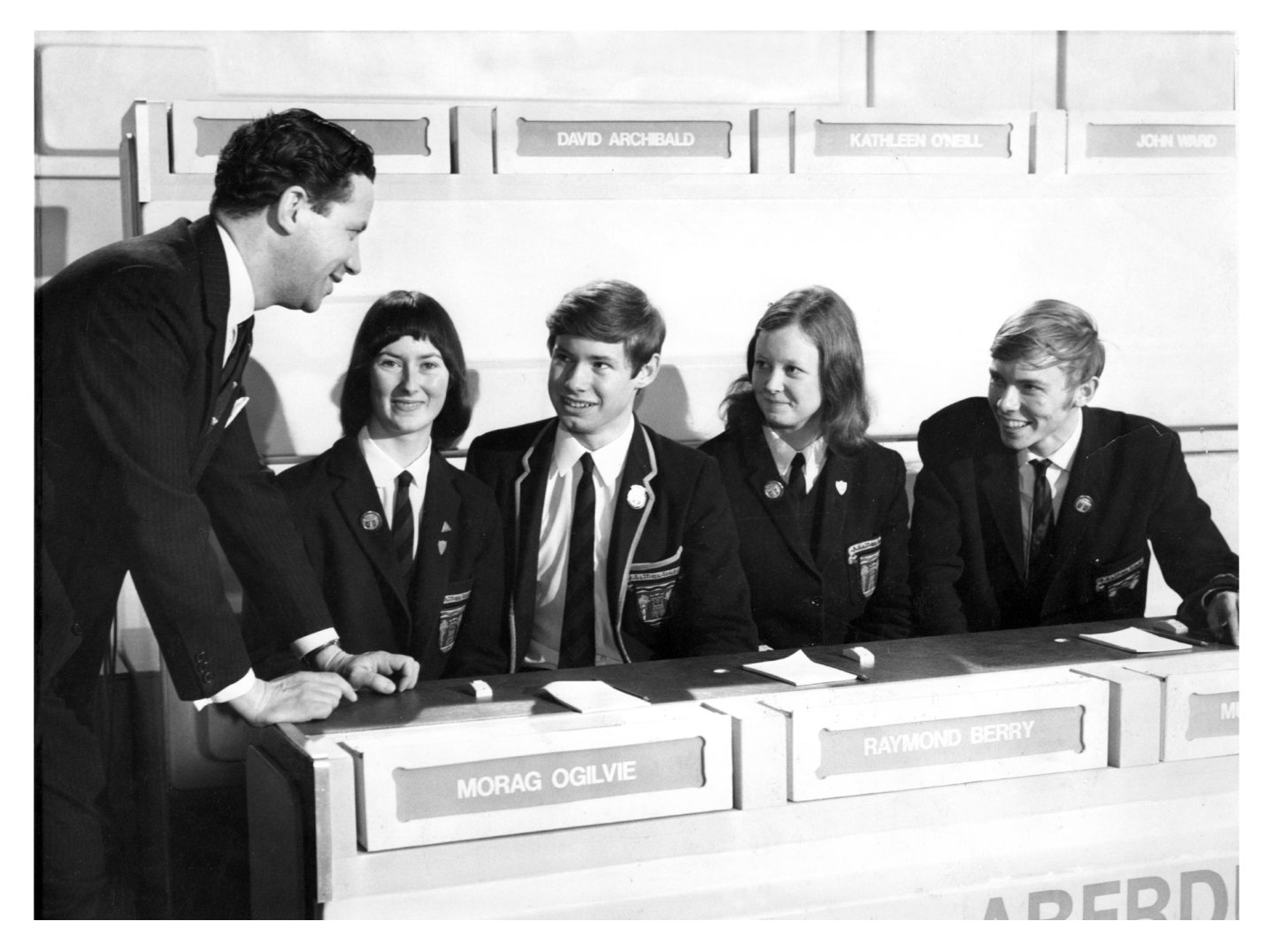

From 1954 it became Ruthrieston Secondary School, going on to become the biggest in Aberdeen with a 1750-pupil roll.

But in 1972, the year of its silver jubilee marking 50 years of secondary schooling, Ruthrieston was to close.

It shut on the introduction of comprehensive education, and merged as an annexe to Harlaw Academy.

Upon its closure, a P&J editorial described Ruthrieston as “pioneering a family of schools which were to become a keystone of the state schooling system in the city”.

The greatest achievement in its last half century was the number of pupils going on to higher education.

In 1962, 22 fourth-year pupils were put forward to sit O-Grade exams, by 1972 that number increased to 104.

Ruthrieston’s legacy continued in the youngsters who went on to universities as a result of its trailblazing secondary system.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

- The school experiment: Linksfield Academy was a bold new era for education in Aberdeen

- Gallery: Summerhill Academy, the trailblazing and controversial Aberdeen school in 90 photos

- The final chapter: Looking back at the history of Walker Road School in Aberdeen

- Balmoral in the East End: Remembering Causewayend Primary School

Conversation