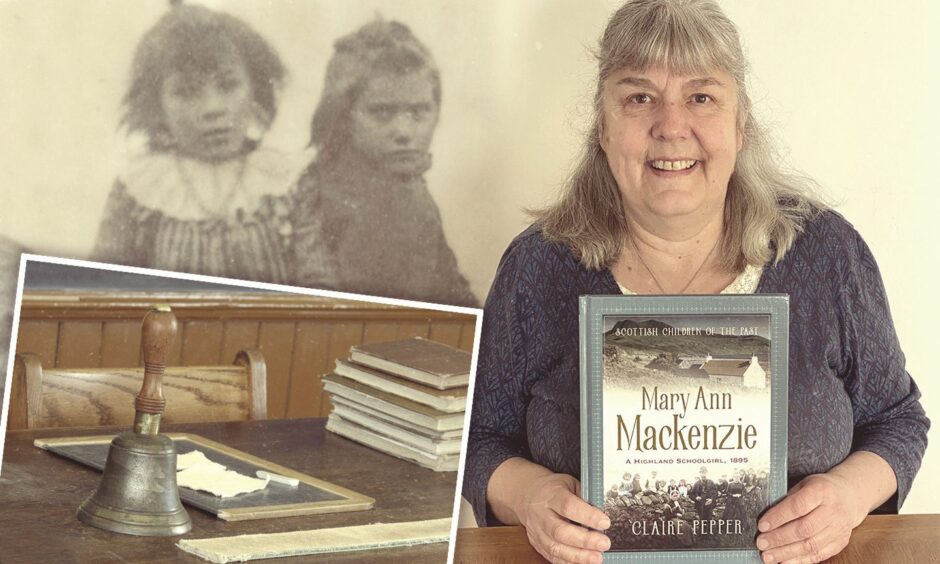

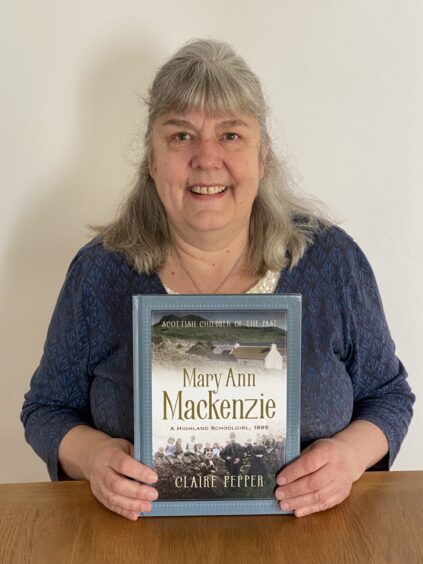

A former teacher at Scoraig school, nearest town Ullapool, was so inspired by her experience there that she has written a book about the life of Mary Ann Mackenzie, a real pupil at the school in 1895.

Claire Pepper, of Gatehouse of Fleet, taught at Scoraig in 2014/15, and found that despite more than a century of a time difference, some things had remained uncannily the same in that remote spot across Loch Broom.

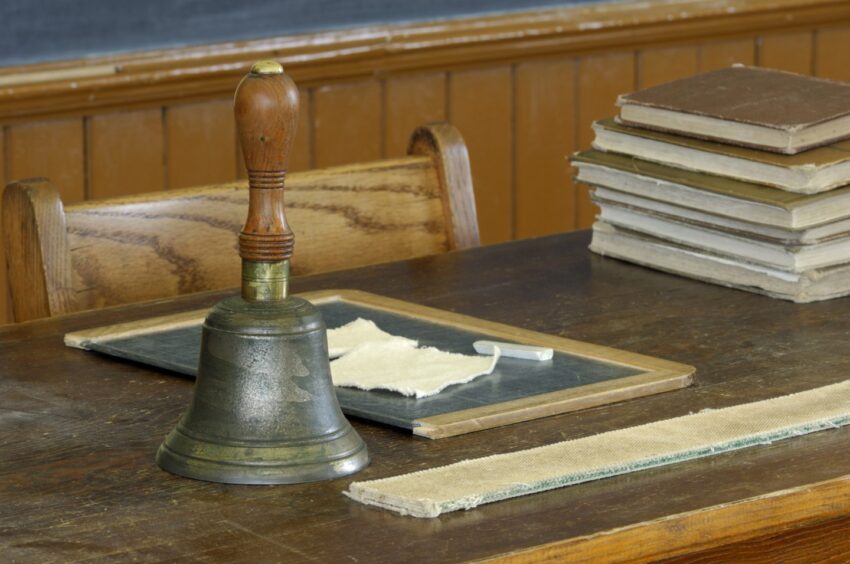

The school building, so familiar to Mary Ann and her four siblings and still in use in Claire’s time, was built in 1860 and still had its high windows, open fireplace and unmistakable signs of mice.

‘When you first enter Scoraig school, it’s like stepping back in time’

Claire said: “There was a bookcase on the wall in the classroom with a glass front, and when I opened it, I found that there were old encyclopedias in there.

“When I looked in the school logbook, I found they were donated to the school by the Coats family of Paisley in 1908.

“When you first enter the school, you enter through a cloakroom built at the beginning of the 20th century and it was like taking a step back in time, the original pegs were still on the wall, the wrought iron stands still in the cloakroom.”

To the cold and draughty classroom, nine-year-old Mary Ann would have made her way daily with her siblings to join 26 other local children, obliged to attend school by the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act, regardless of where they lived and the income of their parents.

A heavy price for education

Education didn’t come cheap if you were grindingly poor, like Mary Ann’s family.

Her father had died at sea when she was only four, and her mother had to work night and day on an unfavoured croft to earn enough to keep the family afloat.

Like all parents, as part payment for her children’s schooling, she had to supply each of them with a clod of peat every day for the school fire.

That must have made quite a dent in the family’s own peat stack.

Weekly fee

Before 1892, the weekly fee for each pupil was one penny per pupil, payable to the teacher at the start of the week.

That’s around £1.60 today, so with multiple children, the burden on poor families was heavy.

Claire writes: “If any child forgot their school penny, they were sent home to collect it as fast as they could run, the teacher’s reprimand still ringing in their ears.

“The children’s school fees were part of the teacher’s salary.”

And running home was no joke for the Mackenzie children.

Barefoot was the norm

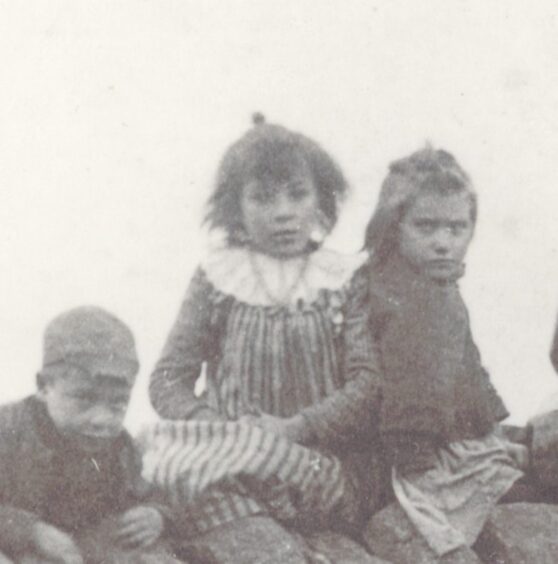

Like many others of their time, they had no shoes or boots, and had to make their way along a rough, muddy drove road following Little Loch Broom, a sea loch.

Claire said: “The maintenance of this path is an ongoing issue, even as far back as 1883 when it was in such poor condition that the crofters living on Scoraig complained they had no communication by road, ‘only by a dangerous rocky mountain which is a hazardous way of travelling, even in daylight’.”

Many children had nothing to protect them from the wild elements and would arrive at school so wet and cold that lessons had to be abandoned for the day.

Claire’s book, aimed at confident readers in P6/7, pulls no punches about the harsh conditions and discipline the children had to endure.

She includes a photograph of barefooted boys from not far away in Poolewe, two of them from families so poor that they were clothed in skirts made from hessian sacks.

Sanitation was a challenge

In Mary Ann’s day, the school toilets were earth closets, located in a small stone building near the main school.

By the time Claire arrived to teach there more than a century later, there was a boy’s toilet and a girl’s toilet, just the one each, the teacher having to share with the girls.

Even in her day, most of the children came from homes with no inside toilet.

Miss Tullo, Mary Ann’s teacher, at least had accommodation in the schoolhouse, but when Claire arrived, where she would stay wasn’t so clear cut as the schoolhouse had been turned into an office/nursery.

Claire turned down an offer of a croft house with an outside drop toilet, a plank with two holes and two buckets, and was ‘relieved’ when the community offered her the use of their wooden bothy, a community facility for running courses and holding events.

There she stayed for the duration of her year-long contract, loving every moment of her time on the peninsula.

Every day practicalities were tough

She soon realised the logistics of getting to and from Scoraig were the reason why everyday practicalities remained almost frozen in time.

She said: “You have to cross Loch Broom, a sea loch, in an open boat and then walk for half an hour along the track. If the weather is too stormy, there’s a five mile track instead.

“I remember someone arriving to fix something at the school with a heavy tool kit. The boatmen offered him a wheelbarrow to carry it to the school.

“The photocopier repair man arrived with his mountain bike though, and was thrilled to bits with the adventure.”

Modern children would be in disbelief

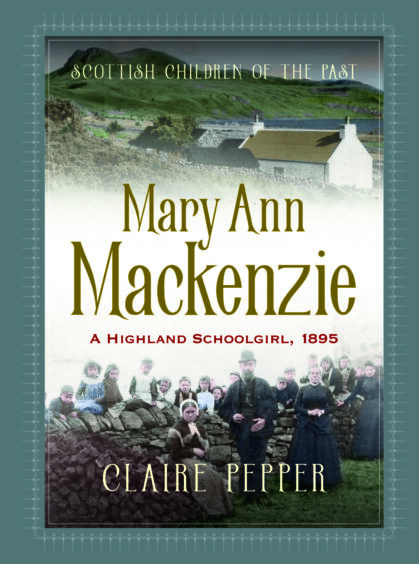

21st century children would find many of the details in Claire’s book, ‘Mary Ann Mackenzie: A Highland Schoolgirl, 1895’, utterly unbelievable, leaving aside the lack of internet and mobile phones.

Prayers at home twice a day, and catechism in school.

Harsh discipline, with the threat of a whack from the tawse for any misdemeanour.

A diet largely of oats, potatoes and herring, limpets and the seaweed dulse. Going hungry wasn’t unheard of.

Sharing three, or more, to a bed.

Working hard on the croft before and after school to help put food on the table.

Learning by rote and copying lines.

One reading book per age group, with no-one allowed to move on until every child had mastered it. This could take weeks.

Using slates and slate pencils, with nothing to clean them with except your own spit. Some children even licked their slates clean, until eventually schools were provided with cloths for the job.

Walking everywhere, usually barefoot. Mary Ann didn’t get her first pair of shoes until she was 13 years old.

Cold, wet, hungry — and facing deadly diseases like diphtheria which often carried children off very young.

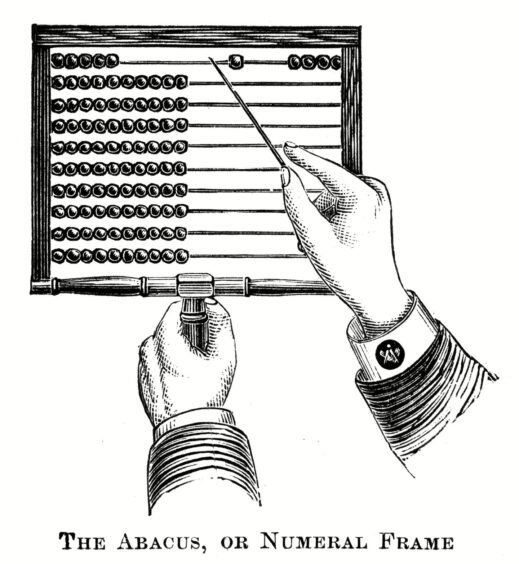

Claire has interwoven Mary Ann’s story with photographs and explanations for the young reader about things they would find incomprehensible, such as the school’s twice-daily written register; the abacus, wooden finger stocks for fidgeting children and how Scoraig children, natural Gaelic speakers were forced to speak a foreign language, English, at school.

What happened to the Mackenzie children?

Claire has managed to track down what happened to Mary Ann and her four siblings.

Sadly, the youngest John, who features as a mischievous five-year-old in the book, died in New York of typhoid aged 22.

Stornoway connections

Her other brother Donald went to work as a shop assistant in Stornoway at 14 and ended up with his own drapery business there. He died in 1953, aged 69.

Her sister Alexina married Donald MacIver, whose father owned the shop on Scoraig. They stayed on the peninsula, helping their mother and rearing their family of three.

Sister Jeannie left home to work in Donald’s drapery shop in Stornoway, returning home often to help her mother. She died in Stornoway in 1936.

As for Mary Ann, she left Scoraig at 13 to work as a nursemaid on the Isle of Ewe. Later she too moved to Stornoway to work in Donald’s shop. She married in 1932 but had no children.

The hardships and privations of her childhood didn’t affect her longevity for she died in Ullapool aged 90.

Book released on May 1

‘Mary Ann Mackenzie: A Highland Schoolgirl, 1895’ will be released on May 1 and available from independent bookshops and museums.

It’s the first book in Claire’s series Scottish Children of the Past which will explore the home life, school experience and employment of real children in Scotland during the 19th century.

The second book ‘Jimmy and Ann: A Boy Miner and a Schoolgirl, Leadhills, 1841’ will be published in November 2024 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Museum of Lead Mining in Wanlockhead.

More like this:

Tilleys, Rayburns and dipping ink: Memories of a 1950s childhood in Sutherland

Treasured way of life: Do you remember mobile shops in the Highlands?

Conversation