As the Tillydrone scheme was built, it was said the rising skyscrapers would lift a community out of squalor and away from social stigma.

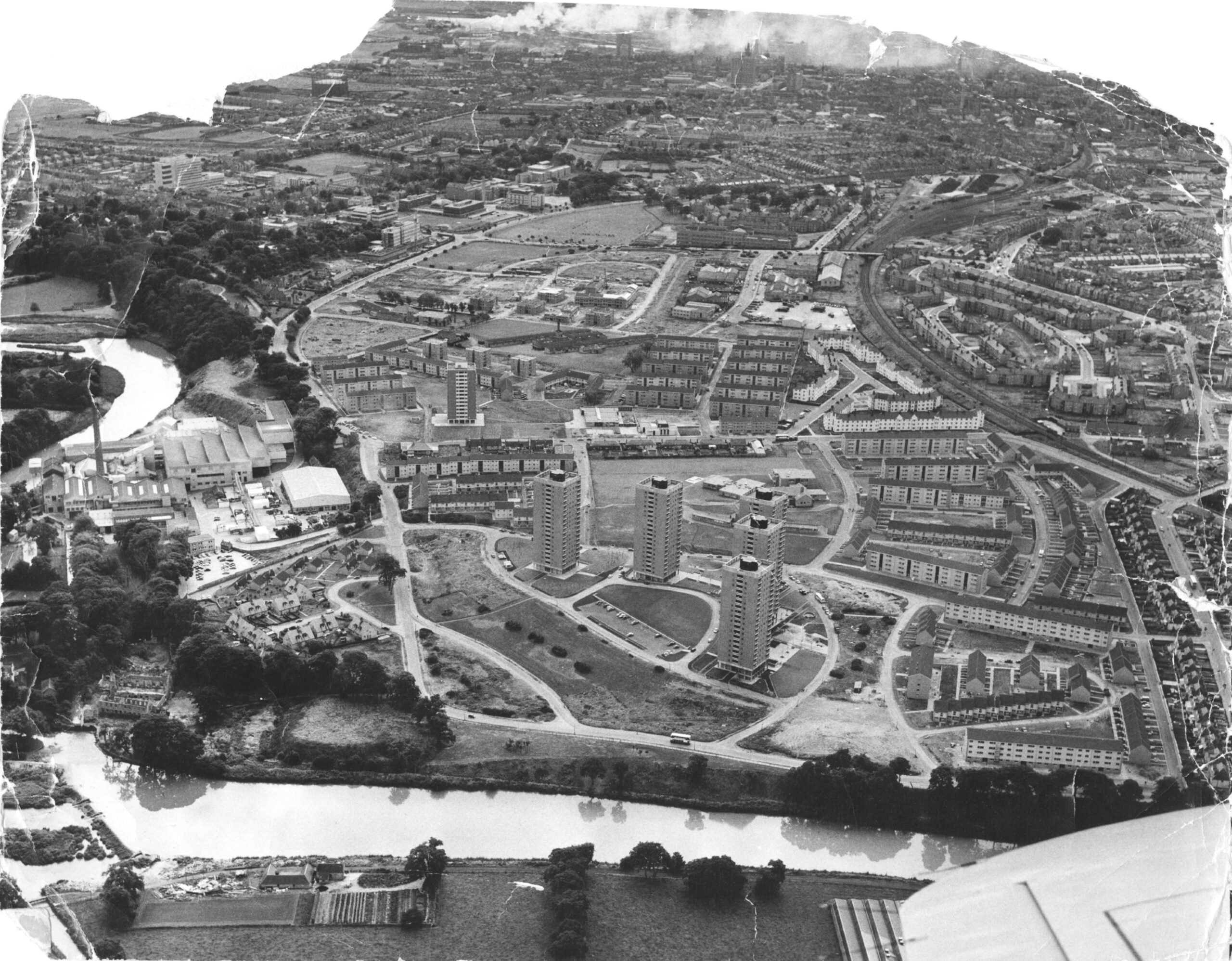

The ambitious development to create a new township in Aberdeen, around the same size of Brechin, began to take shape in the 1960s.

This was a time of rampant, post-war housebuilding throughout Scotland.

Slums, tenements and the bad old days were swept away for modern, sanitary housing – building hopes and dreams, as well as communities.

In the eight years leading up to 1954, 258 new streets had been built in Aberdeen alone.

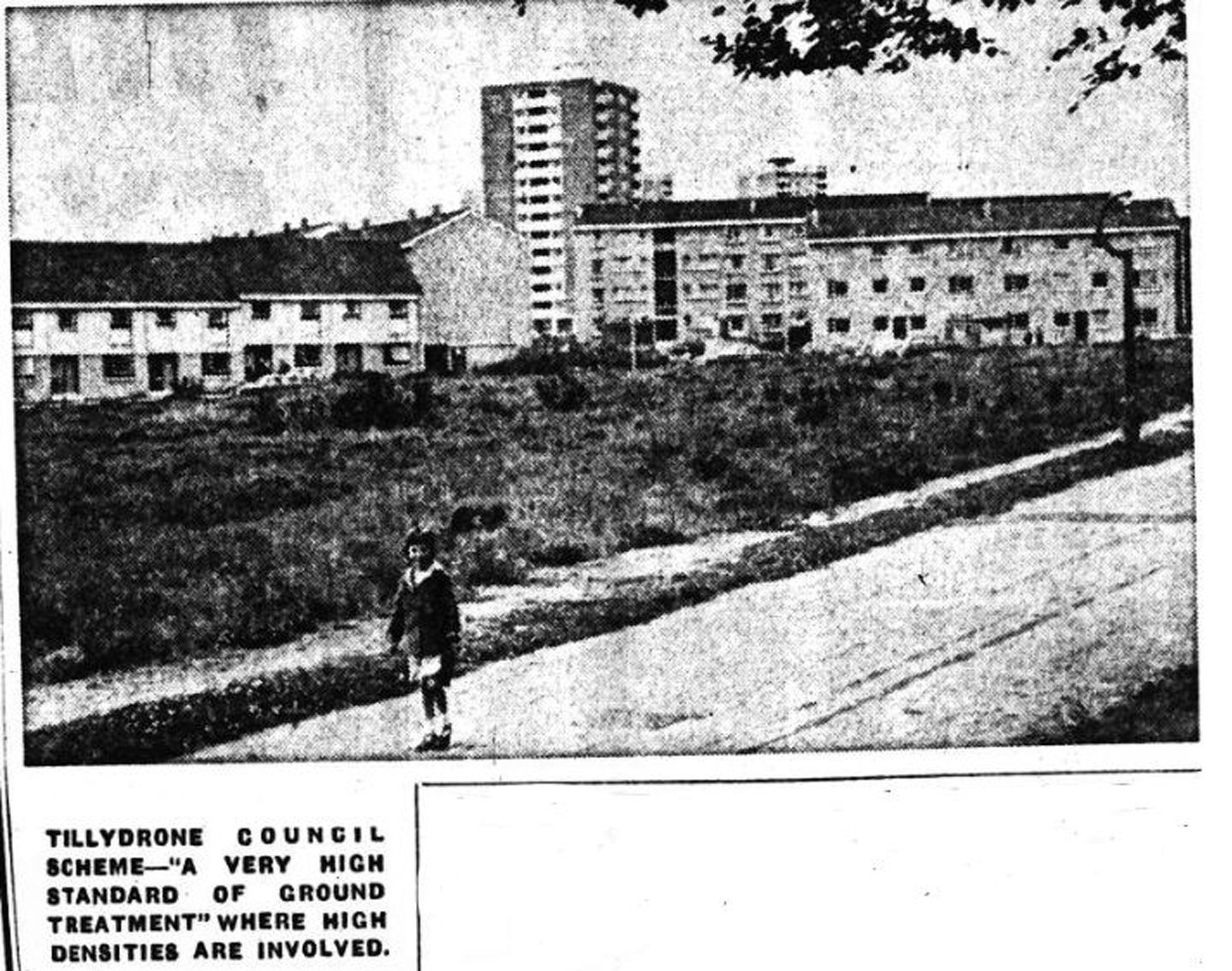

And Tillydrone was meant to be “colourful, different and revolutionary”.

Join us for a trip through the history of Tillydrone, from the post-war 40s, all the way through to the late 60s and beyond…

1946: Homeless Aberdonians sent to live in army huts at Hayton

One of the first areas developed was Hayton, it had been an army camp during the Second World War.

Initially built to train soldiers, it became an Italian Prisoner of War camp.

After the war, Aberdeen City Council became the first in the country to utilise military huts for emergency accommodation.

Housing, or lack of it, was a real problem in Aberdeen after the war, with many families homeless.

Squatting was rife; 23 families squatted in the Balmoral Hotel for six months in 1947 before they were turfed out and into the old army Nissen huts.

But the huts weren’t much better.

1947: Hayton ‘jungle’ was neglected and attracted trouble

Families shared a single room with only a curtain around each bed for privacy, and toilet facilities were shared with other families.

City folk evicted from urban accommodation were “cooped up” in the countryside and felt cut off from the bustle of city life.

They were used to shops on their doorsteps, and were given gardens they didn’t know how to cultivate.

The area became neglected, overgrown and provided cover for “a mindless minority” of criminals, earning the unsavoury nickname ‘the jungle’.

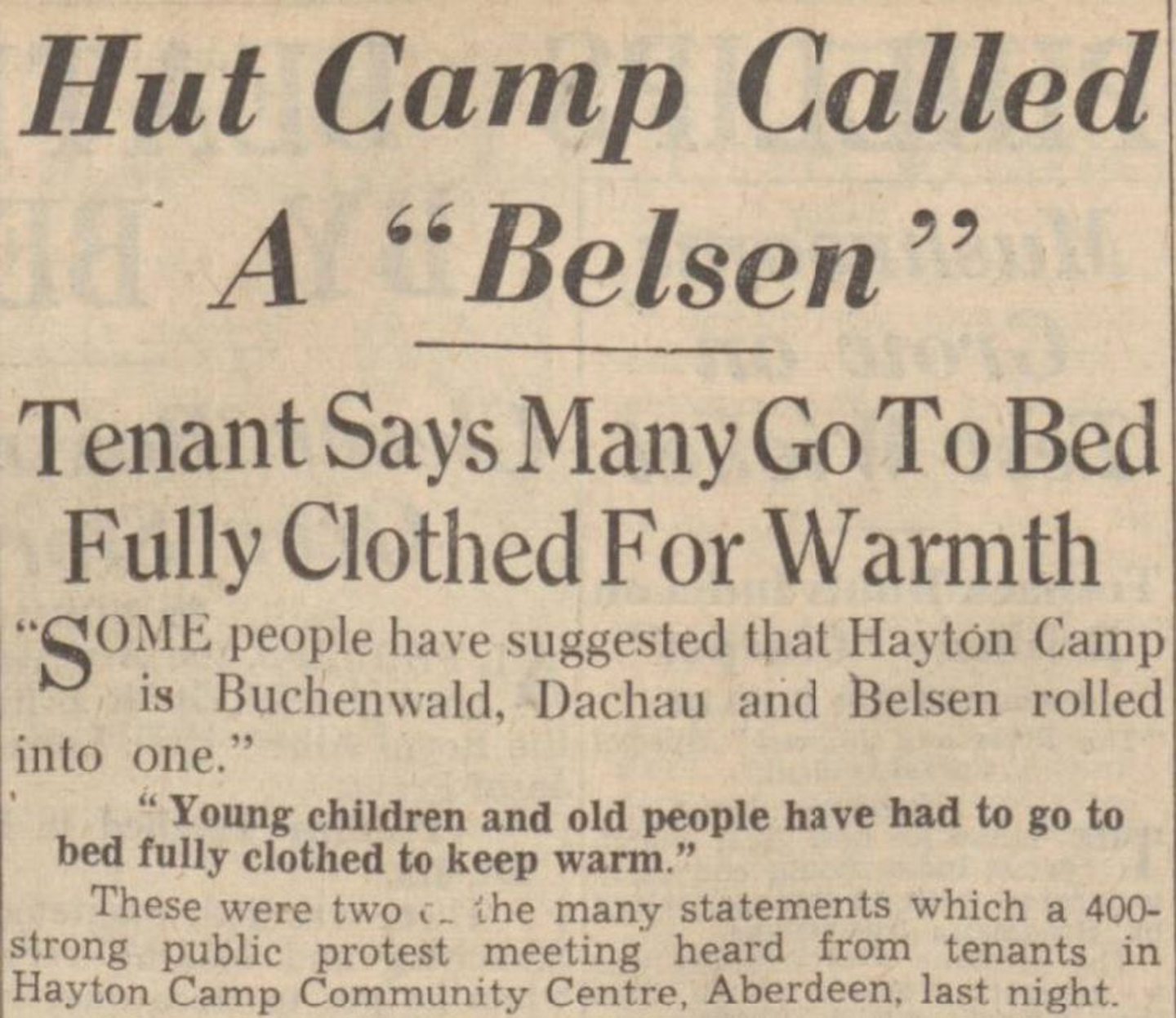

Appalled at the dire conditions, residents formed Hayton Camp Tenants’ Association in 1947 to protest their grim circumstances.

Through shared adversity, residents forged strong bonds.

A public meeting attracted 400 Hayton hut residents who compared the conditions to concentration camps.

Residents were living among rodents, huts leaked, illness and disease was rife, and people were so cold they went to bed fully clothed.

This wasn’t the bright, new post-war world people were promised.

1950s: Community formed in Tillydrone’s post-war pre-fabs

Soon, 600 prefabricated homes were built in Tillydrone, these were a vast improvement on slum tenements and old huts.

For those moving into prefabs, it was the first time many had had an indoor toilet and the space to live without being hemmed in by other families living above, below and through the walls.

As one of the first post-war housing schemes, the streets were named after famous wartime men like field marshals Montgomery and Alexander.

It was by no means luxurious, people still struggled to make ends meet, but a close-knit neighbourhood formed.

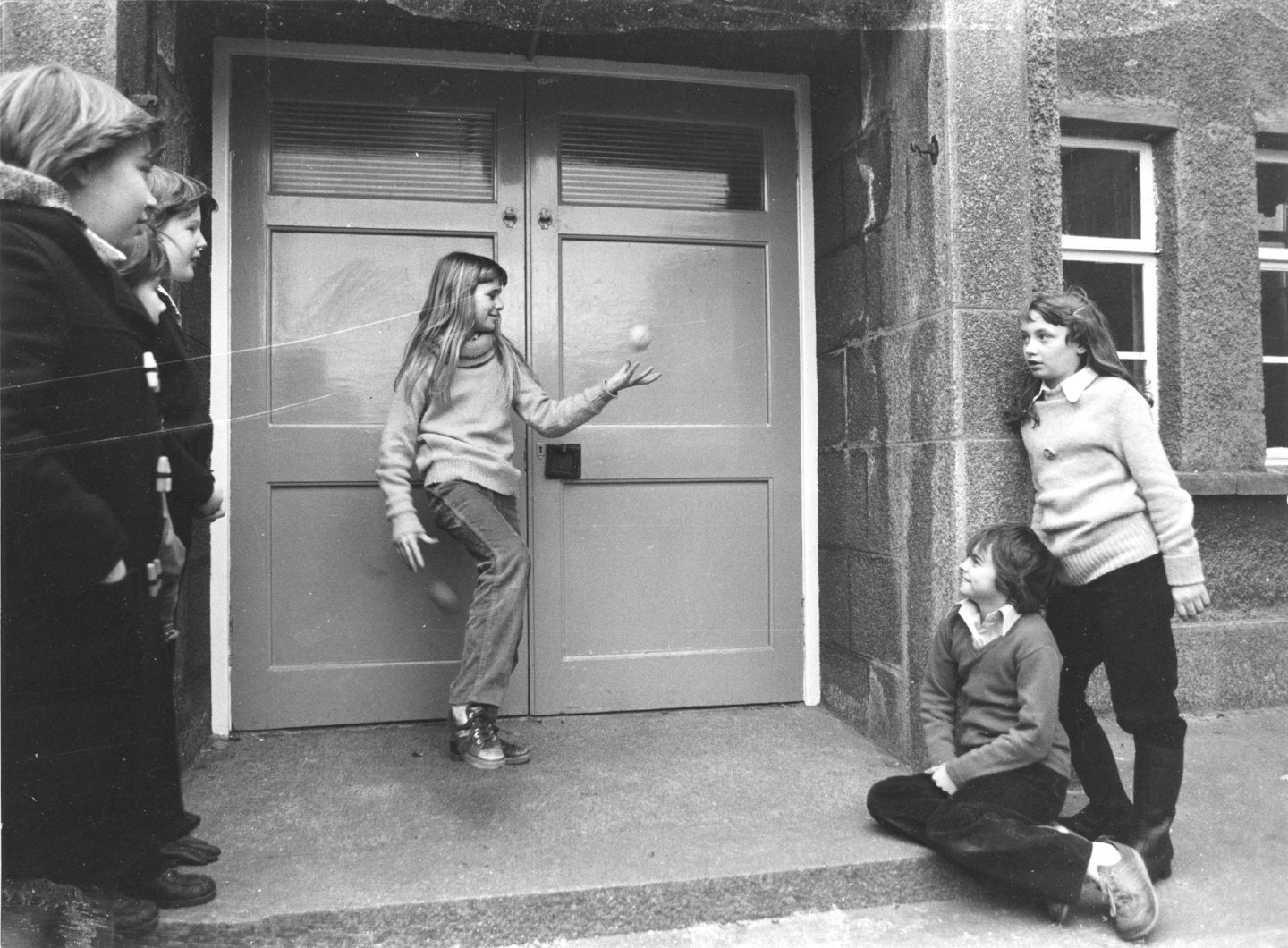

People enjoyed cottage-like houses and gardens, everyone looked out for each other, neighbours became friends and children played on the streets.

Community facilities began to pop up like Hayton Infant School and a clinic, in addition to the shop and chipper, while the old bomb shelters became the playthings of children.

1963: Council promised ‘1000 homes a year’ in 10 years

But still more accommodation was needed, housing waiting lists were spiraling as the city sprawled. The ‘temporary’ post-war pre-fabs were still standing nearly 15 years on.

While new homes were being built, old properties and pre-fabs were being demolished and these tenants needed new accommodation.

In late 1963, then-housing convener Councillor John Greig promised “1000 homes a year for 10 years” in Aberdeen.

But it was also projected it would take four years to clear areas of pre-fabs at Tillydrone, Cornhill and Stockethill.

These vast bits of land were desperately needed for permanent homes.

A tricky balance had to be struck between clearance and rebuilding.

Land needed to be freed up, but to do so, the occupants needed somewhere to go.

1965: Vertical villages in Tillydrone scheme proposed to tackle housing crisis

Come February 1965, the city council approved plans for permanent housing in Hayton-Tillydrone to revitalise the area.

It was also proposed that a shopping precinct, cafes, a church, community centre, play areas, a pub, library and at least one new school would complete the township.

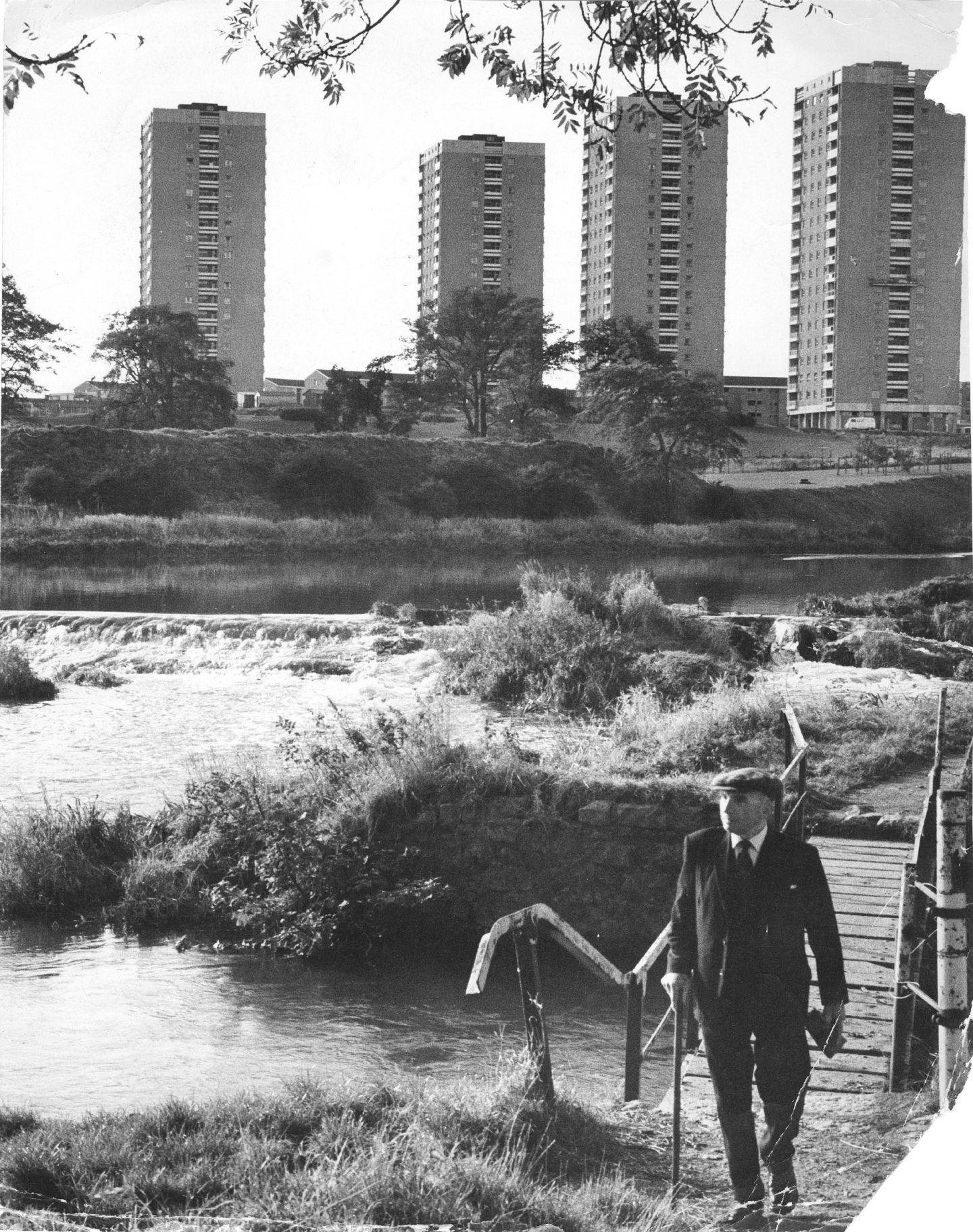

Six skyscrapers – five of them 19-storey blocks and one 14-storey – along with terraced houses and apartments were to form the new Tillydrone scheme.

The development was to create 2243 new homes to accommodate 8000 people.

These vertical villages had a smaller footprint, but could accommodate many more residents, it seemed an ideal solution.

Progress was quick, but as the high-rises “mushroomed” concerns were raised about the fact they were “not intended for families with young children”.

The reported reasons were they were “not easily accessible for mothers with youngsters; little or no play space; and communal services, like lifts and wash bays, that are not suitable for little, inquisitive hands”.

But this would be a utopia compared to the daily trudge mothers took through the badly-lit ‘jungle’ with their babies to reach the only clinic.

Although residents had long been removed from the Nissen huts, the council made a mistake by not demolishing them.

Squatters and petty criminals took advantage, and it was rife with gambling, drinking, prowling and poaching.

Mid-1960s: Tillydrone tower blocks aimed to shake off stigma

The Tilly tower blocks were not just a housing development, it was also a fresh start and a civic experiment.

The community was a driving force in shaking off the ‘jungle’ reputation, they wanted to grab this opportunity with both hands.

Such was the reputation of Hayton – undeserved for the vast majority of those living there – that residents asked for the name to be dropped from the new development.

It was simply to be ‘Tillydrone’.

With a fresh start, it was hoped this would elevate the civic status of the community, while the clean, contemporary facilities would overcome the stigma.

There was a burgeoning pride as the buildings rose from the dubs.

1968: Hayton residents faced ‘unfair slurs’

Then-Hayton Community Centre warden George Mitchell kept residents abreast of developments and helped foster self-worth among neighbours.

He said: “This community has been unfairly slurred in the past.

“The good folk of the area have never been given a chance. Some very decent young folk have to give their grandparents’ address if they hope to get a job.”

In spite of its issues, a solid core of good citizens “built up a resistance to their surroundings”.

The community-spirited people of Hayton won the inter-community centre quiz league and they raised funds to send a young boxer to the Scottish championships.

They established judo and climbing clubs, there was a gardening club, galas, flower shows and contests – healthy competition raised standards and morale.

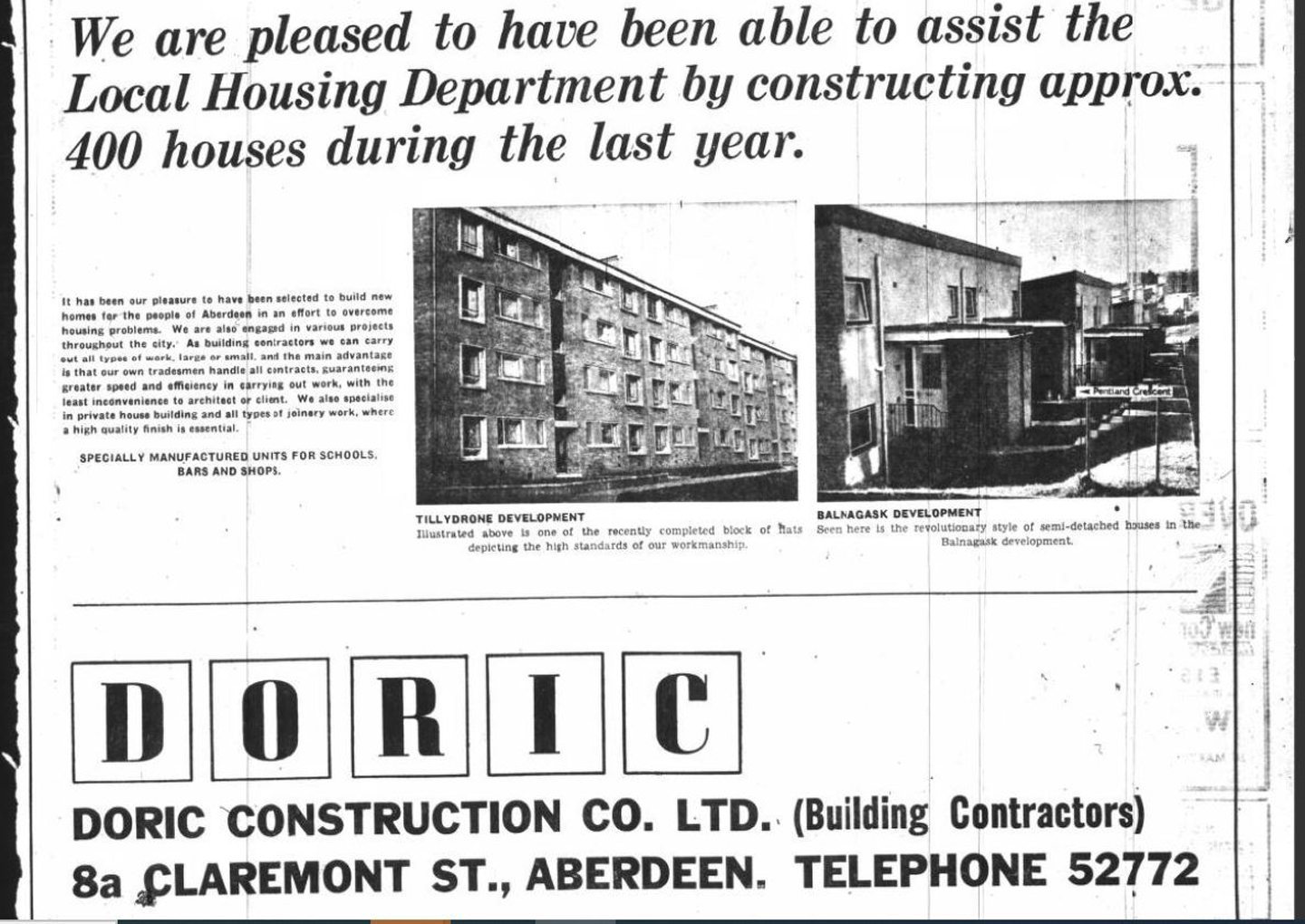

1968: Tillydrone scheme helped city council surpass aim to build 10,000 homes

As the development neared completion in late 1968, it was said the success of the new Tillydrone scheme would depend on the people.

But it also depended on good housing stock.

Unlike other cities that have since torn down their post-war modernist high-rises, those in Tillydrone and the rest of Aberdeen were built to last.

Granite rubble was cast into the concrete giving the tower blocks a unique appearance that weathers better than plain concrete render.

Inside, tenants enjoyed panoramic views over the city in bright and spacious apartments within gleaming skyscrapers.

The successful Tillydrone development played a huge role in the council achieving its promise of building 10,000 homes in a decade.

In fact, by 1969, the council was on track to have built 11,000.

Late 1960s: Tillydrone became self-sufficient township

Housing schemes on the perimeter of the city boundary became satellite communities in their own right.

Each had shopping precincts meaning residents didn’t need to traipse into the city for groceries.

The first shop to open at Tillydrone Shopping Arcade was the butcher E Kane and Son.

Ernest Kane had previously run a shop at Stockethill and his son Gordon had one in Mastrick.

Soon the Kanes were joined by a Spar store owned by Mr Forbes, and a dispensing chemist shop owned by Lewis Duncan.

At the relocated Post Office were familiar faces Mr and Mrs Watt. They were already firmly established in the community having run their business at Tillydrone’s Tedder Street for 12 years.

Another shop in the line-up was RS McColl where locals could pick up toys as well as tobacco.

1969: Street name changed to shake off bad reputation

But not everyone who had put down roots in Hayton wanted a slice of the high life in the high rises.

Many were content in the old housing stock in their established neighbourhoods.

However, residents were keen to shake off the indelible and unfavourable image cast upon their community in the post-war years.

Kilgour Avenue and Kilgour Gardens residents, along with ward councillors, appealed to the city council streets and works committee to have the street names changed.

Such was the poor reputation of the street that people were snubbed in job applications if their address was given as Kilgour.

Then-councillor Thomas Paine said Kilgour was right at the entrance to the new Tillydrone development and added “surely the people are worthy of being part of us”.

He was annoyed by the stigma attached to Kilgour and added: “People seem to think that because someone comes from Kilgour they are doomed.

“We are trying to get rid of this idea of Kilgour being a unit unto itself.”

Isabella Colbert, tenants’ association founder, said the move was to make local kids’ lives better in the future.

She explained: “It does spoil you from getting a job. I really hope things will change.”

Fellow resident John Robertson said: “I think it will be better. If you mentioned Kilgour when you were after a job that was it.

“Alexander used to be used for the prefabs round about here and that was a good area.”

1969: Architect revealed Scandi inspiration behind Tillydrone scheme

It was agreed to rename the streets and to absorb them as part of the now-acclaimed Tillydrone estate.

The finished scheme was considered a success “and a complete contrast to the greyness for which the Granite City has become world-famous”.

Charles Pressley, the city council architect behind the development, visited the estate with the Evening Express in 1969 to reveal his inspiration for Tillydrone.

As a student he gained scholarships to Scandinavia and was particularly taken with a group of multi-storey flats he saw in Bergen, Norway.

When he sat down at the drawing board to design the Tillydrone housing, the Norway model stuck in his mind.

He said the concept of many buildings close together seemed impossible, but the Scandi scheme showed it could be done.

The five Tilly blocks were arranged so that, despite their proximity to each other, each got the sun for a long time each day, and so the shadows from one block did not fall too much on the others.

But it wasn’t just about the scale, Pressley was very particular about the buildings in relation to the people who used them.

1969: People and their relationship with buildings at heart of design

It was the largest scheme in the city where pedestrians and cars were largely segregated, to promote safety and outdoor play. Play areas included tree trunks for children to clamber over, and concrete pipes to crawl through.

While one of the distinctive features in the scheme was the coloured panels beside the windows in the terraced housing.

These injected colour into Tillydrone, but they had an important purpose beyond aesthetics.

Pressley explained: “They serve to identify various blocks. You have to do this, for this is mainly a pedestrian scheme.

“You tend to identify your house by its relationship to other things, like colour and shape.

“And they are especially useful for toddlers, who may not be able to read numbers, but will recognise colours.”

The fact Tillydrone was mainly a pedestrian scheme was another reason for using colour on the buildings.

Pressley explained it didn’t matter if cars have a boring route, but it was important routes for people were “as interesting and varied as possible”.

1969 onwards: ‘Tillydrone is wonderful’

Mr Pressley was a regular visitor to the scheme in the months and years after it was completed, and always said it “excited” him.

And in 1972, the Meadow Court part of the development went on to be awarded a Saltire Award for design.

Pressley’s quiet pride was eclipsed by the joy of some residents. Many of whom had come from caravan sites in the city to their first bricks and mortar home.

Finally, this was the realisation of the modernist housing people expected after the war.

New to Tillydrone was Eleanor Simpson who got a flat on Alexander Drive. She told the Evening Express it was “a marvellous scheme”.

She added: “The flats are wonderful and easily kept and there is plenty of room for the children to play.”

Eleanor described how she loved being able to walk safely into the nearby countryside with her three-year-old, Brian.

While some residents had minor quibbles (not enough playgrounds, rotary driers weren’t big enough to dry sheets and blankets), the overwhelming consensus from the community was: Tillydrone is wonderful.

It did lift people out of squalor, however, the stigma was harder to overcome.

But, despite its problems, the Tillydrone estate succeeded architecturally in bringing “a touch of the continent to Aberdeen”.

And the deep sense of community first established decades ago still endures today.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation