By the middle of June 1964, it became clear the typhoid outbreak in Aberdeen was under control and declining.

Confirmed cases were declining rapidly. The public health campaign seemed to be working and Aberdonians were washing their hands like never before.

The city’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr Ian MacQueen, gave the nod. “Things will be back to normal by July,” he said.

The front pages moved on.

But it was the start of a horrific chapter in the life of one Aberdeen teenager.

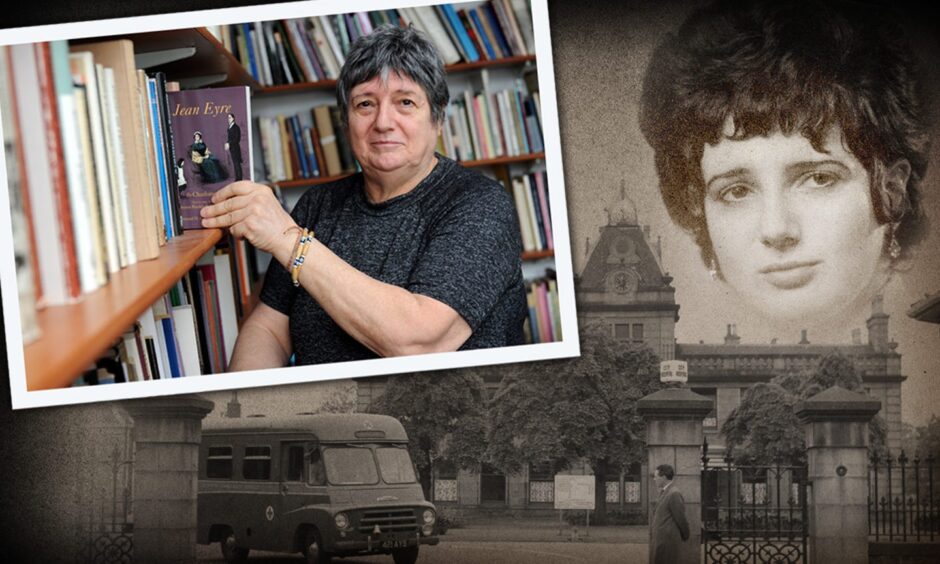

For 16 year old Sheena Blackhall, it wasn’t the end of the epidemic at all, it was the beginning of a nightmare for her.

She lived in Albert Terrace, Aberdeen, and was due to go to Gray’s School of Art in the autumn.

But her street was gripped by a creeping nightmare. Typhoid had broken out at No. 2, and a month later had reached Sheena’s home at No. 15.

“My mother shopped at William Low in Holburn Street”, Sheena said.

William Low was later pronounced to be the source of the outbreak. (The supermarket’s reputation was damaged beyond repair and it closed three years later.)

“We got boiled ham from there, but it had gone through the same machine as the corned beef.

“That’s how I got it, but no-one else in my family did. On the day Dr MacQueen said the epidemic was over, I went down with it.”

For Sheena, typhoid was life-changing

Typhoid put her in hospital for three months and kept her well below par for a year.

Consequently, she failed at Gray’s, and felt forced into primary teacher training, which she had no enthusiasm for.

The first she knew of her illness was when she developed a migraine, and was very sick with a rocketing temperature.

Her family GP, Dr Alistair Forbes knew immediately what it was as he’d seen the same thing in Japanese POW camps. He called an ambulance.

Then the hallucinations began.

The paramedics wore white coats, and Sheena was convinced they were seagulls.

She was admitted to the City hospital, the official fever hospital, to a male diabetic ward where she was given male PJs and a safety pin to make them decent.

The treatment was black and red capsules of Penbritin antibiotic, 16 per day for a year.

Life on the isolation ward was grim

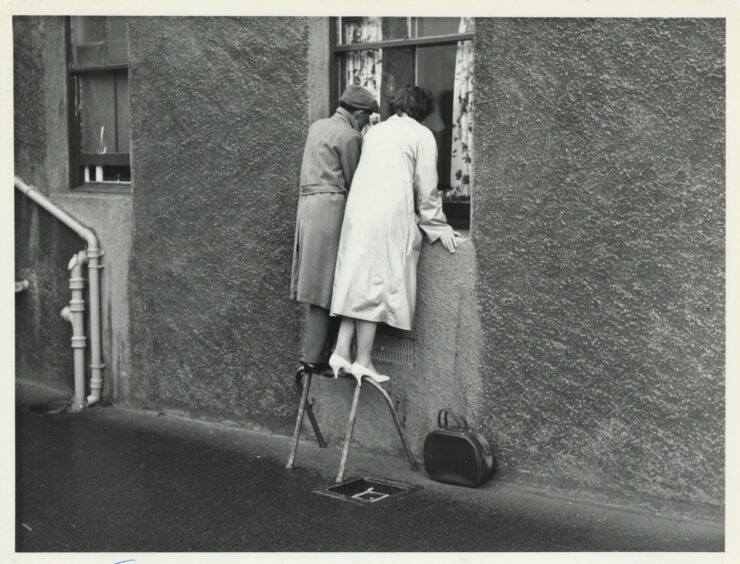

Families weren’t permitted into the hospital to visit their loved ones, and could only look in through the windows.

Sheena said: “You weren’t supposed to wander about, but there were families in there, and husbands and wives used to meet in the grounds for a canoodle.

“The staff knew but turned a blind eye.

“One day I found out there was a Ballater girl I knew on another ward so I went to visit her, which I shouldn’t have done, but I lost track of time and missed the doctors’ rounds, and that’s how they found out people had been breaking the rules.

“They clamped down, and I was sent to Coventry by the other patients.

“Also the other women were glued to a set of binoculars on the ward, looking at Broad Hill which was across from us.

“It turned out this was a haunt for prostitutes and their punters, but the women would never let me have a look.”

Sheena lost 3 stone in her battle with typhoid

She said: “It was the best diet ever. Everyone lost weight. You just couldn’t eat. It was like Belsen.”

Apart from her mum and dad, Sheena only had two visitors, one from the shire, and a schoolfriend who brought her a book on Mussolini, she recalls.

“Being locked up was horrible. There were babies and toddlers there. I was told the disease affected people’s nerves, and they could be very nasty.

“It affected my liver and kidneys for a long time afterwards.”

It wasn’t until after she got out of hospital that Sheena found out how badly the city had been hit.

“It was also the end of my aunt’s coach business, Strachan’s Deeside Omnibus Service.

“It had been struggling the face of growing car ownership and typhoid was the final nail in the coffin.”

For Sheena the biggest upheaval in her life was having to leave a career in art behind.

“I had no interest in writing, but I decided to create word pictures.”

Perhaps thanks to typhoid, Sheena is now Aberdeen’s makar, a celebrated poet, novelist, short story writer, illustrator, traditional story teller and singer, both in Doric and in English.

She’s just completed her 200th poetry pamphlet.

In another quirk of fate, she found herself in hospital at the start of the Covid pandemic, not with Covid but different condition.

She said: “It reminded me of the typhoid outbreak. They hadn’t even got masks or PPE when I was in.”