When the Astoria Cinema flung open its doors in Kittybrewster 90 years ago, it was the most modern cinema Aberdeen had ever seen.

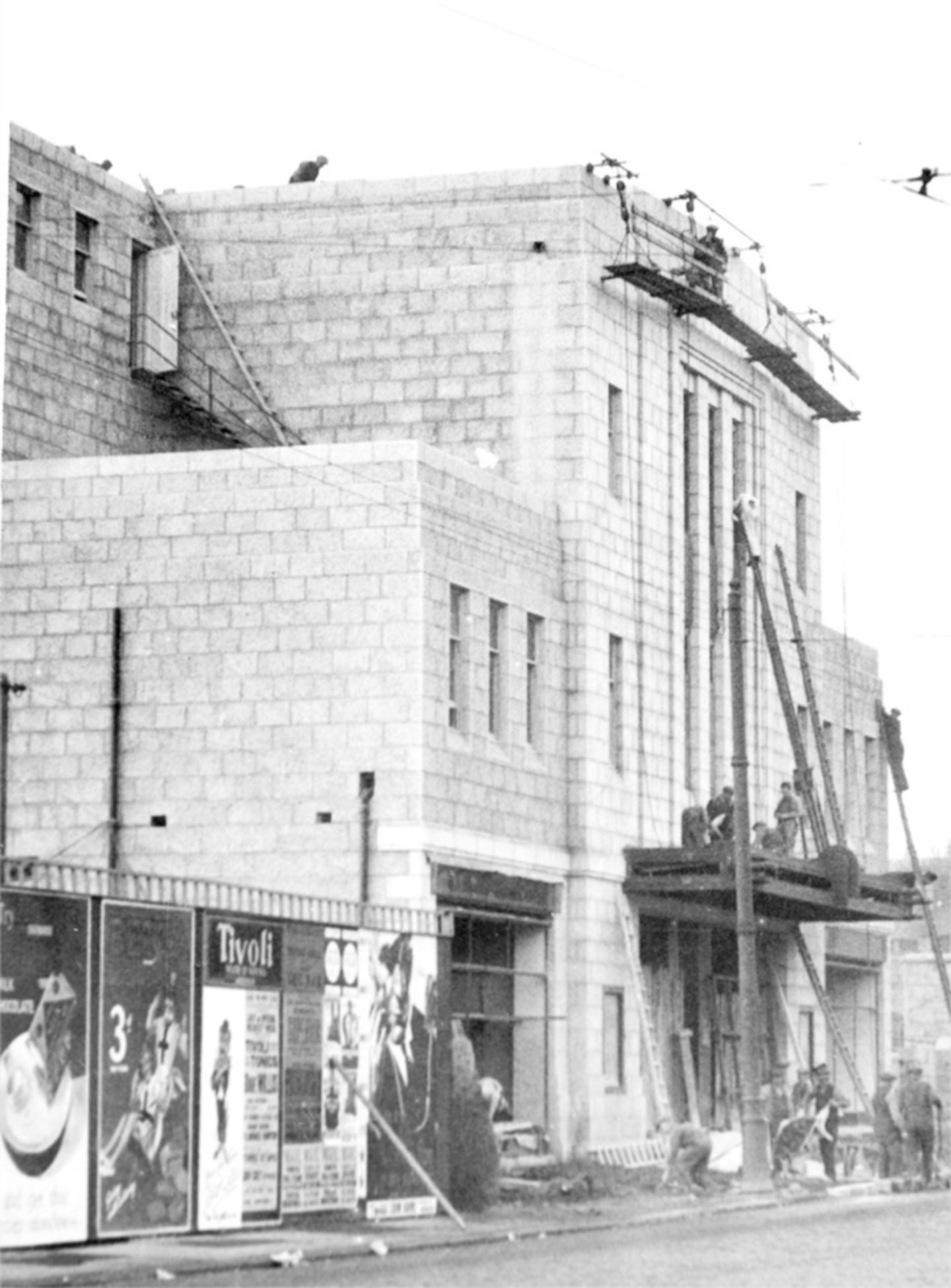

Its avant-garde, clean Art Deco lines were in stark contrast to the grubby, old agriculture buildings around it.

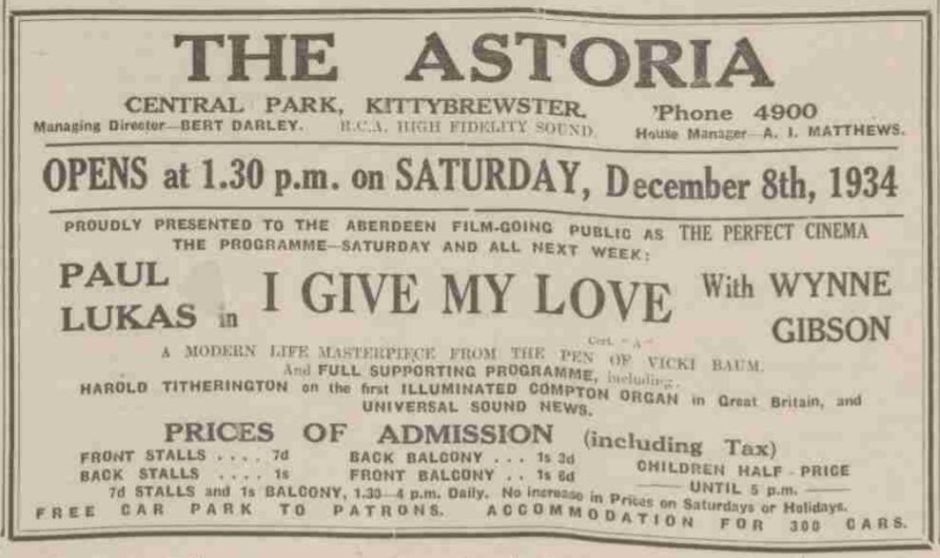

Opening in December 1934, the 2060-seat venue was a trailblazer for cinema design in Scotland.

Astoria was Art Deco super cinema

It was a “super cinema” built on a vast site called Central Park in Kittybrewster, just north of Kittybrewster Auction Marts.

It was Aberdeen’s biggest suburban cinema, and in the days before multiplex – at a cost of almost £3 million – no expense was spared.

Unmistakably Deco, the cinema was another vision of the Aberdeen architect T Scott Sutherland.

His plans described how the imposing granite facade was “built on sumptuous lines”, while inside, viewers would enjoy the latest in screen technology.

Everything for the luxurious Astoria, except the organ sound equipment, was built or handmade in Aberdeen to the tune of £40,000 (£2,927,595 in today’s money).

Cinema dazzled under neon lights

The whole frontage was electrifying – illuminated day and night in blue, yellow, green and orange neon lighting.

Nicknamed ‘liquid fire’, the spectacular neon lighting continued under the canopy and into the foyer.

It was the first cinema of its kind in Scotland to pioneer such a dazzling display.

The huge foyer was akin to the entrance to a grand mansion with walnut panelling.

Stepping into the “lofty and dignified” foyer was like walking into a palace.

In 1934, the average Aberdonian would have felt like a film star sauntering onto a glamourous Hollywood set.

Two miles of carpets needed to cover floors at 2000-seater Astoria

The roof was built in a series of sloping steps to create the best acoustics.

The colour scheme was light pink, ivory and brown to complement the finest walnut wall panelling, while the solid walnut doors were adorned with cast bronze fittings.

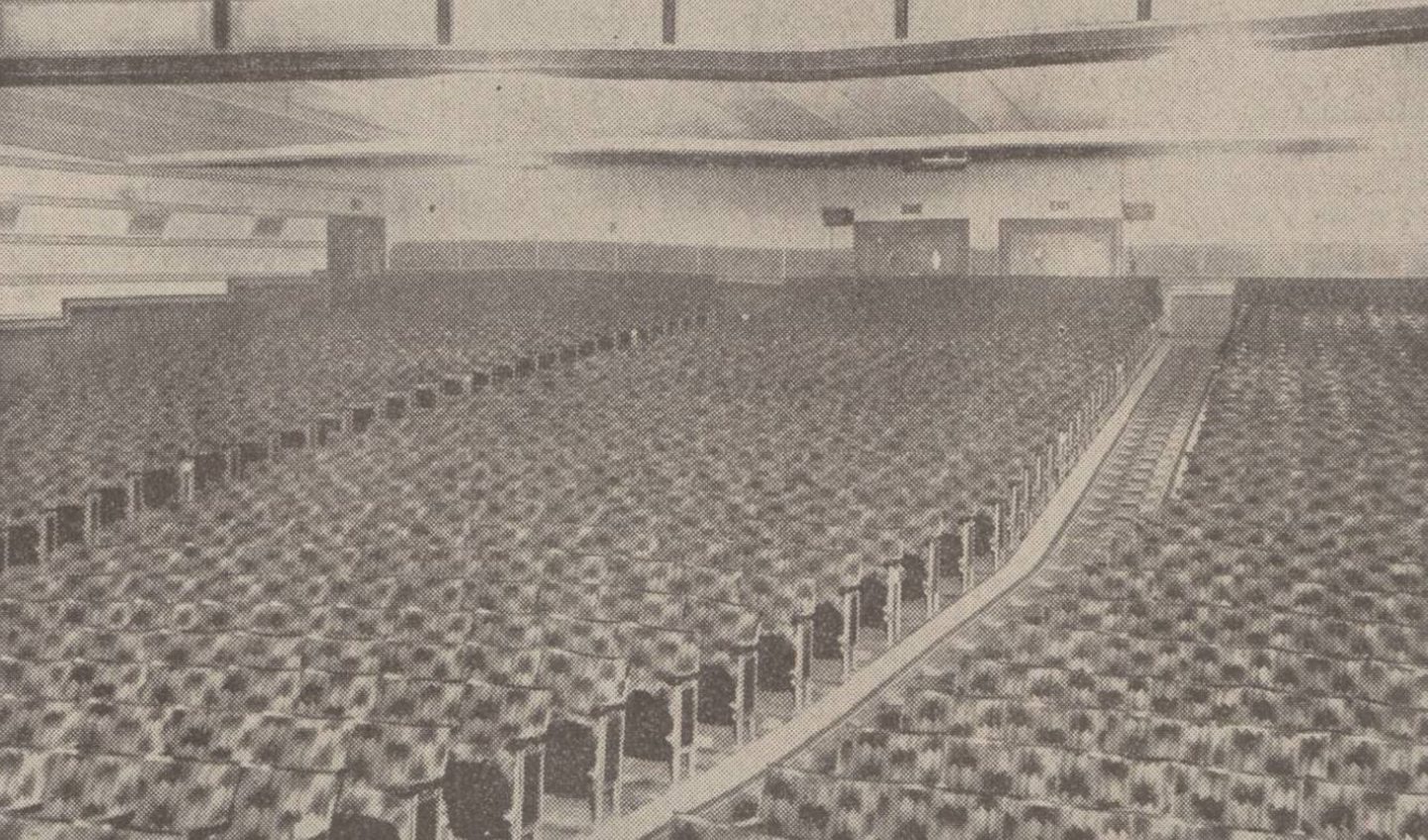

Two miles of green and brown plush, patterned carpet covered the floors, to “harmonise” with the mile of brown and terracotta moquette fabric needed for the seating.

Around 30 tonnes of castings were needed to make 2060 tipping chairs for the main auditorium, and it took 102 local men and women five months to upholster them.

A soft, carpeted sweeping stairway lead to a balcony and lavish lounge, as well as a boardroom and offices.

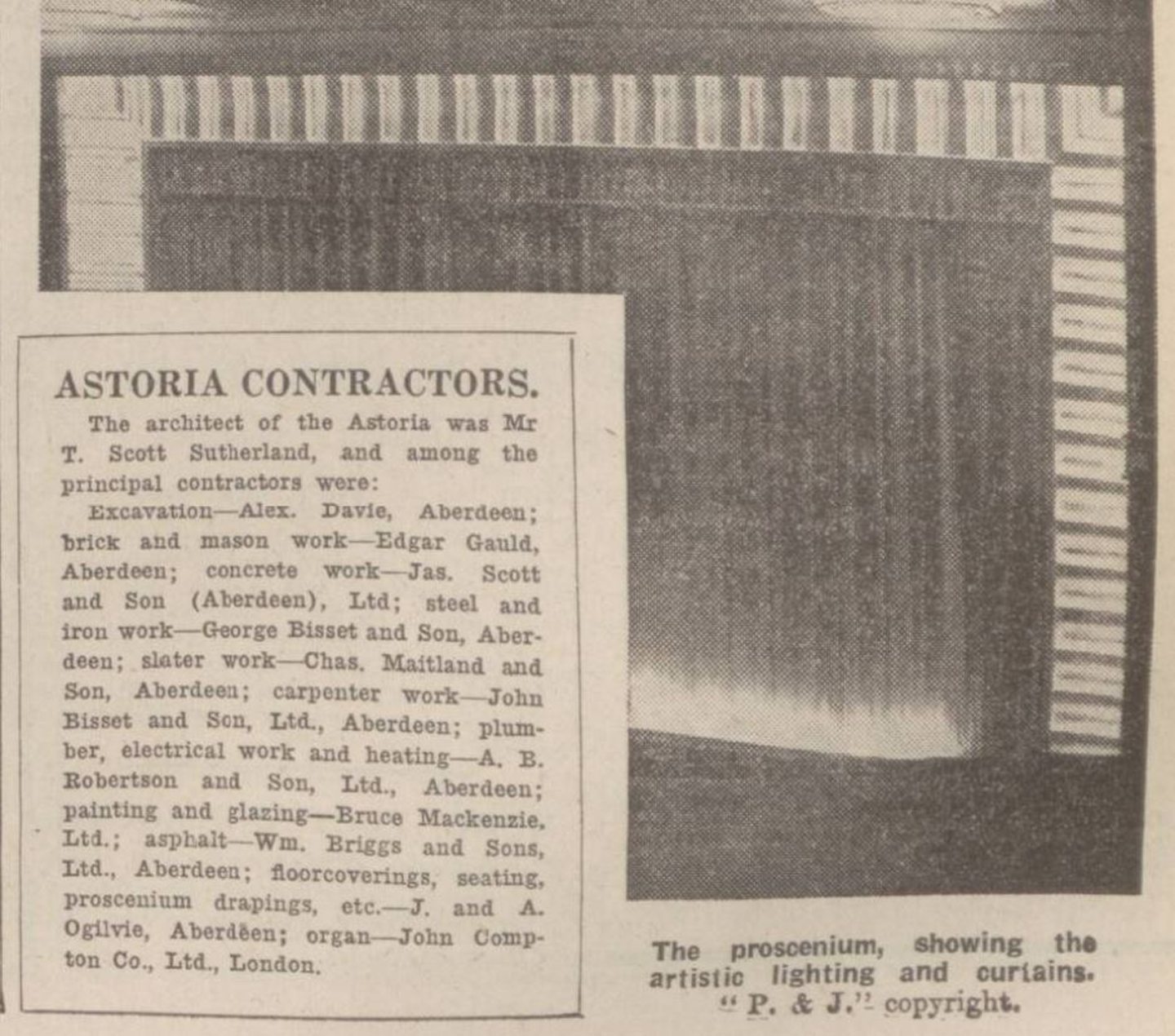

Proscenium was ‘work of art’

But the jewel in the crown was the huge proscenium – the archway framing the stage – which was dressed with opulent green curtains and silver screen made of satin.

Kinematograph Weekly, the British film trade magazine, said: “One of the most striking features of the Astoria is its proscenium, which really is a work of art.”

Debuting the latest developments in cinema lighting, the proscenium featured red, blue and green hues.

Debuting the latest developments in cinema lighting, the proscenium featured red, blue and green hues.

These colours could then be blended through a specially-made modern mixer to project hundreds of different shades into the auditorium.

Cinemagoers were in for an audiovisual experience like no other, and when it came to the projector, only the best would do.

While outside, the free car park could accommodate 300 cars, designed so the first car to arrive would be the first to leave.

Special feature was Compton Organ

Managing director for the new Astoria was Bert Darley, who was an actor in his early days.

He had cut the first sod for excavation work to begin in June 1934, and it would open just six months later.

Ahead of the opening, Bert said: “Above all, modern cinemas require highly efficient film equipment.

“The sound-recording system is the first of its kind to be installed in Scotland.

“It is of the RCA (Radio Corporation of America) type, with high fidelity horns and a RCA super-simplex projector.

“The result is that difficult sounds to reproduce, such as the crumpling of a piece of paper, can be faithfully reproduced.”

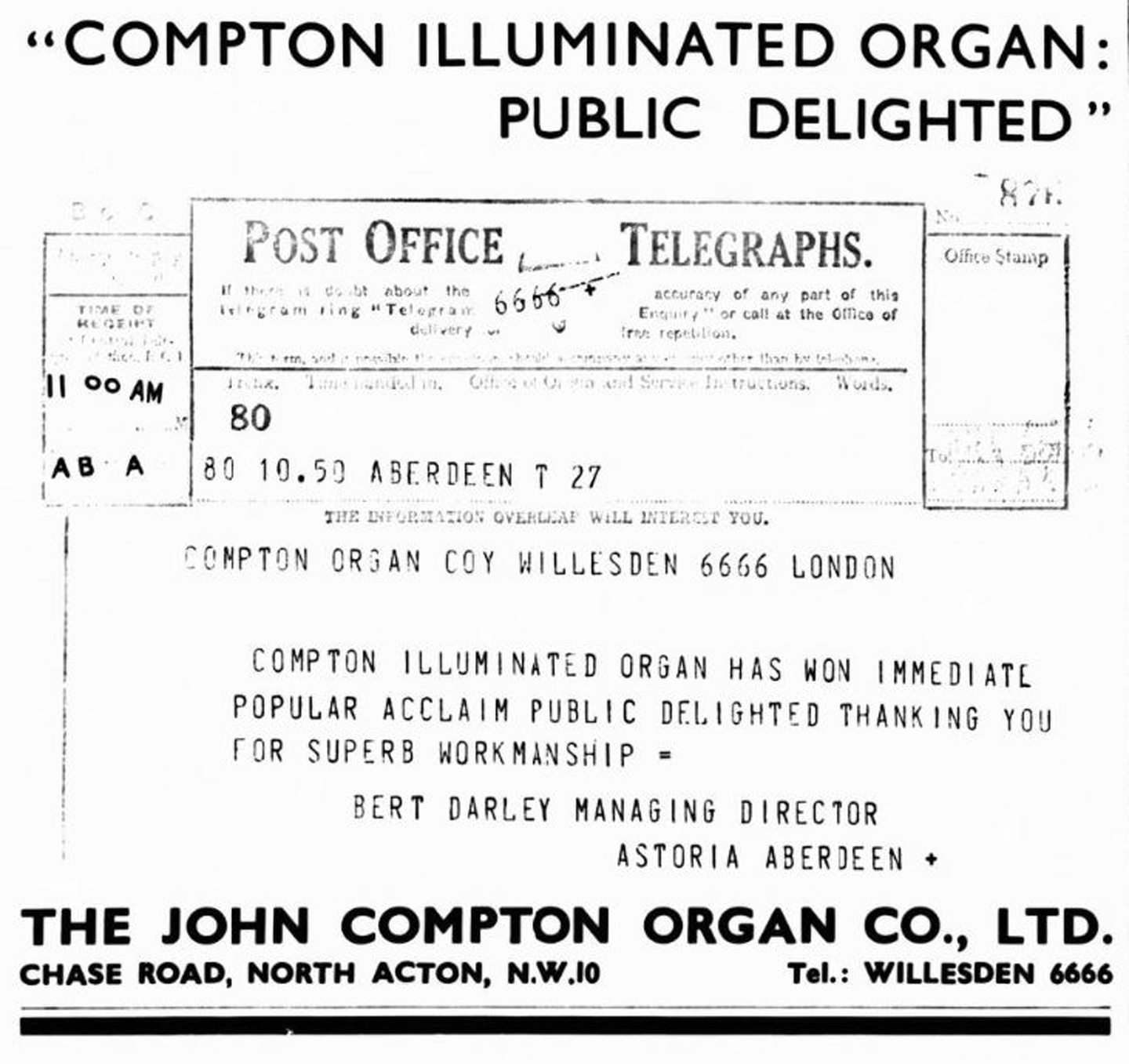

In addition to technology, a special feature of the Astoria was a Compton organ – the first in Scotland to be illuminated, and only the second cinema in Aberdeen to have its own organ.

The eye-catching organ was also mounted onto a kind of railway so it could be pulled onto the stage.

Local pensioner carried out official opening of Astoria Cinema in Aberdeen

Excitement and anticipation built ahead of the Astoria’s opening, but it wasn’t a silver screen starlet who performed the opening ceremony on December 8 1934.

Instead, the grand honour was bestowed upon 72-year-old Robert Gibb of nearby Cattofield Terrace.

The local pensioner took such an interest in the Astoria that he visited the building site daily – including Sundays – since work began.

The first film shown was ‘I Give my Love’, starring Paul Lukas, with the Astoria’s Harold Titherington accompanying on the illuminated organ.

Admission prices were 7d for the front stalls and a shilling for the back stalls, with children half-price until 5pm.

Venue survived wartime bombs, but not decline in cinema

The cinema went from strength to strength, and the Astoria provided other-worldly escapism during the war years.

Although its popular organist Bobby Pagan was called up to serve in the Royal Navy.

When on leave, he would come back to the Astoria and delight audiences with his organ playing, and after being demobbed in 1945 returned for good.

The cinema itself escaped a near-miss itself during the Aberdeen Blitz when a 500kg explosive detonated just west of Kittybrewster Station on the other side of Great Northern Road.

But with the rise came the fall – cinema dramatically fell out of fashion in the 1960s.

The Astoria, despite its innovations, wasn’t immune.

Like many other palatial picture palaces in Aberdeen, it closed in August 1966 before reopening two weeks later as a bingo hall.

But just four months later it closed for good, to be replaced with a shopping precinct.

Astoria Cinema taken down girder by girder in 1967

Little over 30 years after the state-of-the-art Art Deco masterpiece was built, it was pulled down stone by stone, girder by girder in 1967.

Stripped of its sumptuous interiors and roof, all that remained was a steel skeleton, before it too collapsed into the dust.

The special organ was offered for sale to nearby Powis Academy, music master at the school Robert Leys, along with 10 senior pupils, dismantled and removed the instrument.

The youngsters traipsed up Great Northern Road carrying organ pipes, but it was another year before it was restored to working order, taking centre-stage in the school’s assembly hall.

Sadly the organ was lost during a devastating blaze when a former pupil set fire to Powis Academy in 1982.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation