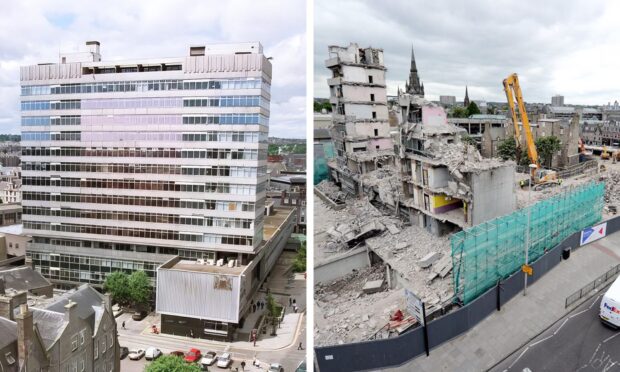

A whole 10 years has passed since St Nicholas House was demolished, disappearing from Aberdeen’s skyline forever.

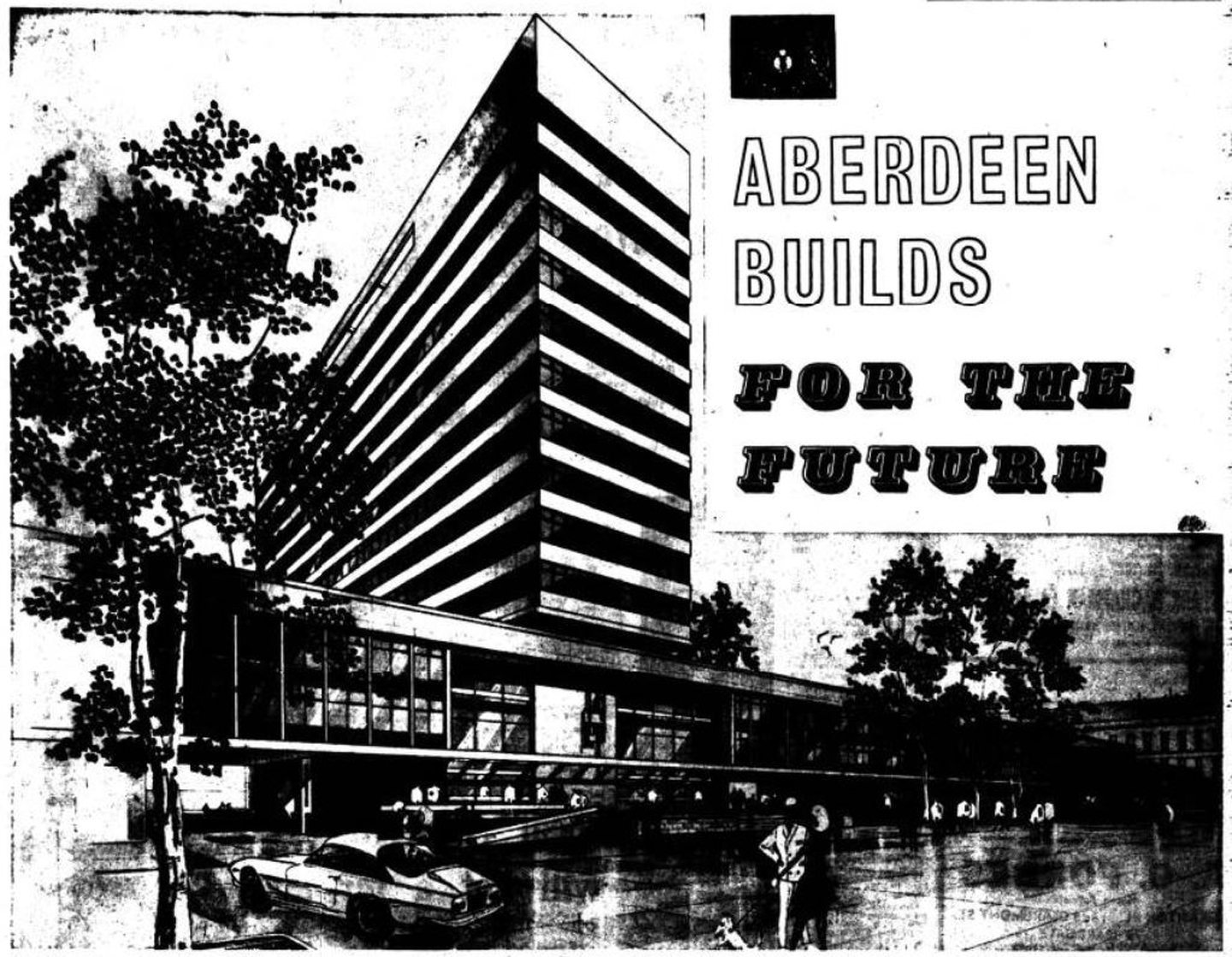

When the concrete building began to rise from Broad Street in the 1960s, it was said “Aberdeen builds for the future”.

But fewer than 50 years later, St Nicholas House – a building Aberdonians loved to hate – was carefully picked apart floor by floor.

St Nicholas House cost nearly £2 million to build, and it cost nearly £2 million to demolish.

The final stage of demolition over the summer of 2014 was like a public post-mortem of Aberdeen’s failed 1960s architecture.

Far from building for the future, the 15-floor building quickly looked older and shabbier than the historic buildings it overlooked.

As often happens, the old ways and the old materials triumphed over the new.

Aberdonians were not keen on St Nicholas House plans

Even at the time, Aberdonians were not enamoured with the plans for St Nicholas House.

But this isn’t a criticism of the architect George Keith. The towering office was of its time.

Never again could architectural landmarks like Marischal College, Woolmanhill Hospital or the majority of Union Street be built.

And perhaps they too were considered gaudy and modern at the time.

The construction of solid granite buildings had tailed off by the 20th Century – by then it was mostly used as cladding or facing.

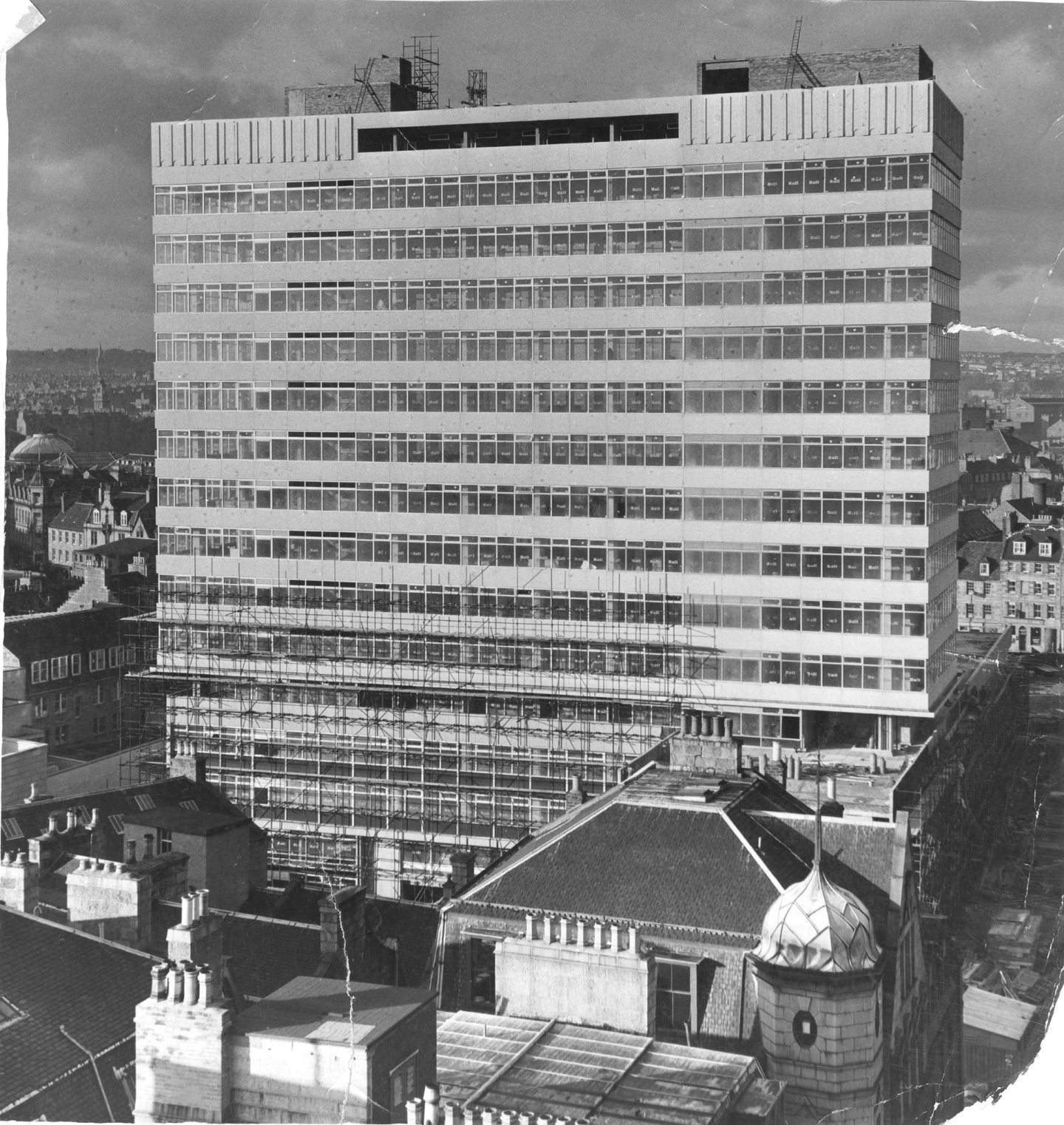

And by the 1960s, the architectural standard was concrete, open plan, large plate-glass windows and flat roofs.

Heritage and restoration in planning was in its infancy. Why keep historic but tired, grey granite buildings when you could have a modern “municipal marvel” like St Nicholas House?

New council HQ would tower 170ft over city

When Mr Keith unveiled his vision for the council’s flagship building in 1961, it had been years in the making.

In 1956, Lord Provost Stephen said no business in Aberdeen would tolerate the conditions council staff worked in.

But with no space to build outwards in the city centre, the only way was up – 170ft up to be precise.

Mr Keith did not intend to build a high-rise, but as more departments were to be brought under the same roof, more floors had to be added.

St Nicholas House was never going to sit comfortably with the grandeur of Marischal College.

It was a tricky brief; a practical office block could never compete with the council’s Town House – the city’s civic heart.

So, the tower was designed at right angles with Broad Street, with just three storeys facing Marischal College, wrapping around Provost Skene’s House.

St Nicholas House was scaled back when budget was rumoured to be slashed

Builder and contractor JK Hall said: “I am confident that when it is completed it will be an outstanding example of a civic centre and of modern architecture.”

It certainly stood out, and it was certainly modern.

Initially St Nicholas house was to be built in three phases. As the first got under way in 1965, the face of Broad Street changed forever.

But, with rumoured budget cuts halfway through, a planned glass-fronted walkway linking Union Street and Netherkirkgate was dropped.

Mr Keith was said to be hurt by the criticism of his vision, which was never fully realised.

Inside, the building contained ‘novel features’ like moveable walls. And instead of conventional ventilation, it had suspended ceiling tiles that ‘breathed’ through porous holes.

Compromises during build caused problems years down the line

More than 600 council workers were housed at St Nicholas House when complete in 1968.

Until then, staff were scattered across offices, converted houses or former shops in Carden Place, King Street, Bon-Accord Crescent, Broad Street and other locations.

There was a staff restaurant on the top floor, an underground car park, and “three high-speed lifts that could travel 500ft-a-minute”.

The city council architect department was one of the first to move in, the well-lit office was a welcome contrast to the ‘rabbit warren’ of small rooms it had occupied at number 11 Broad Street.

And while St Nicholas House was not popular, the memories it held for council staff – many of whom would have worked their entire careers there – cannot be overlooked.

But, far from being the future of Aberdeen, compromises during the build created problems further down the line.

The high-speed lifts were often out of order, and although structurally sound, St Nicholas House was long afflicted by heating problems and a crumbling exterior.

St Nicholas House became city’s most-loathed building

A mere 30 years after it was finished, even the council couldn’t hide its desire to see the back of its HQ.

Its defects meant it cost them £150,000 a year to maintain.

And by the year 2000, Councillor Len Ironside definitively told the Evening Express the council was to get rid of St Nicholas House and that it had “never been very pretty”.

A poll revealed it was Aberdeen’s most-loathed building.

Its demolition was proposed as part of a radical transformation of Aberdeen’s built heritage, where it was suggested Marischal College could become a luxury hotel, and the Salvation Army Citadel could be sold off.

But even then there were question marks over what could become of the site, which although lucrative had its limitations – namely parking and conservation.

Then-chairman of Aberdeen Civic Society Norman Marr said it would have to be a sympathetic redevelopment.

And he added: “It would be wrong to leave the land as open space, as historically the site was a maze of courts and housing.”

Forensic flattening of St Nicholas House skeleton in 2014

But St Nicholas House clung on until 2014 before the wrecking ball moved in.

Council staff were to move into the refurbished Marischal College as part of a plan announced in 2003.

It was a piecemeal demolition. Safedem had to forensically strip the tower block back to its frame, carefully removing asbestos and other fittings.

Slowly, floor by floor, the skeleton of ’60s town planning shrunk and returned to dust.

In photos: Going, going, gone – the demolition of St Nicholas House

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation