I grew up with my grandma Peggy’s enthralling stories of wartime Aberdeen when rationing was the norm. But what was everyday life actually like for her generation in the Granite City during those dark days?

This month marks 70 years since the end of rationing in 1954, a whole nine years after the war itself ended.

Without glorifying war, or trivialising the sacrifices made, the anniversary got me thinking about how Aberdonians like my grandma put food on the table.

Life on the home front was hard – not to mention the imminent threat of death by bombing.

So, I decided to carry out an experiment.

I lived for a week strictly on the wartime rations that grandma would have worked with in her wartime kitchen.

What I discovered gave me a whole new appreciation for my grandmother, and what she – and a whole generation in Aberdeen – endured.

Read on to find out:

- What my toddlers thought of a lentil curry that looked like the contents of a nappy

- My battle to make cabbage palatable

- My grandma’s experience dodging bullets while shopping on George Street

- The extra benefits we vegetarians got in the war

- And if I’m going to keep any of these wartime meals in my family’s regular menu…

Meet my grandma Peggy Ross

But first, let me introduce my grandma who grew up in Kittybrewster.

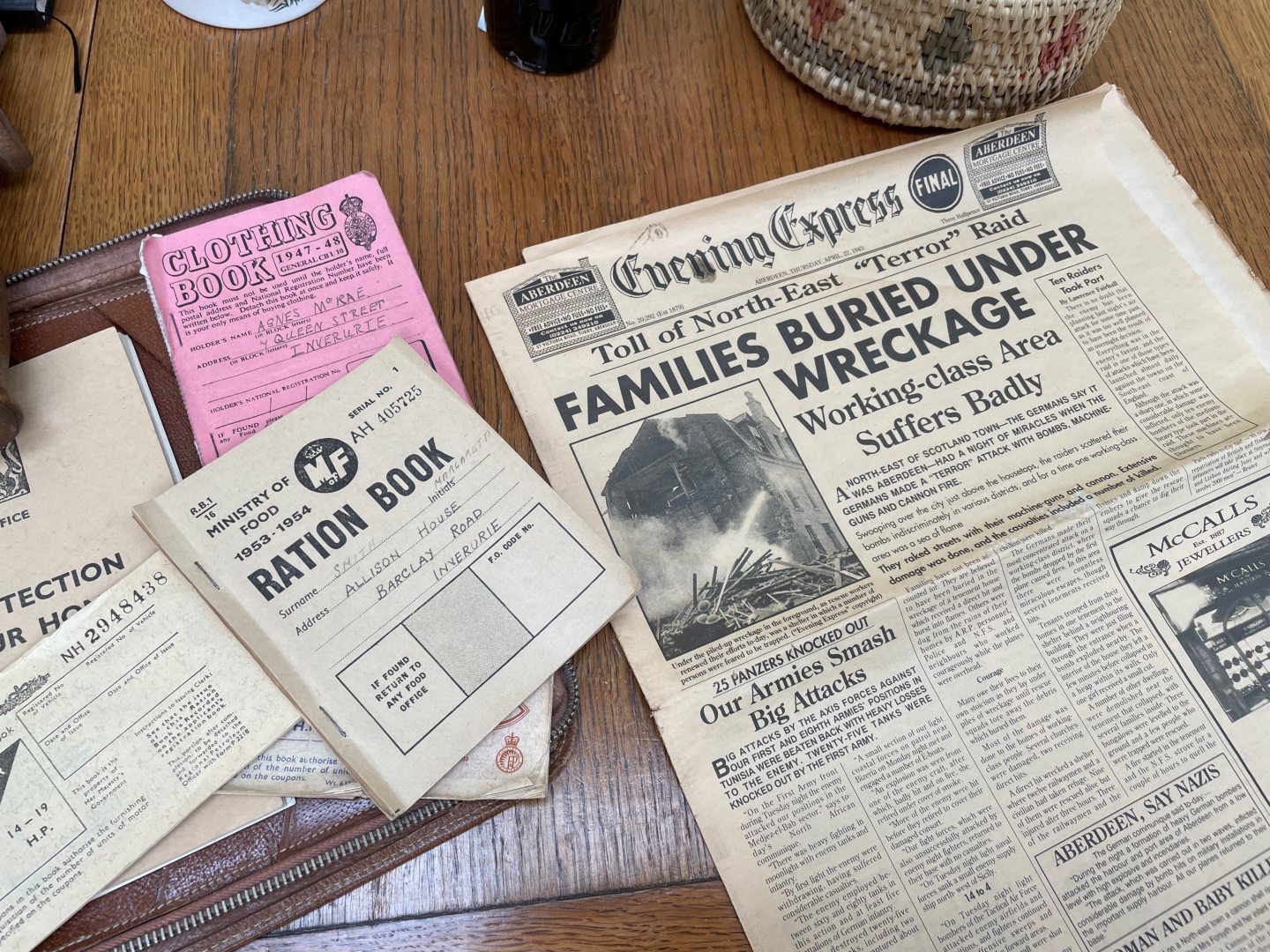

Margaret (Peggy) Ross was almost 19 when the Second World War broke out.

Like many young women of that era, she married, set up home and had her first two children during the war.

Engaged on Christmas Day in 1939, two years later her new husband would be away at war.

She also worked for the Navy Army Air Force Institute (NAAFI) in Aberdeen.

The NAAFI provided support to the forces, running canteen and leisure services for troops.

Food was in short supply during the war; prior to the conflict around 70% of Britain’s food was imported.

Rationing was introduced in January 1940, to ensure fair distribution of resources, but as the war wore on, food became more scant.

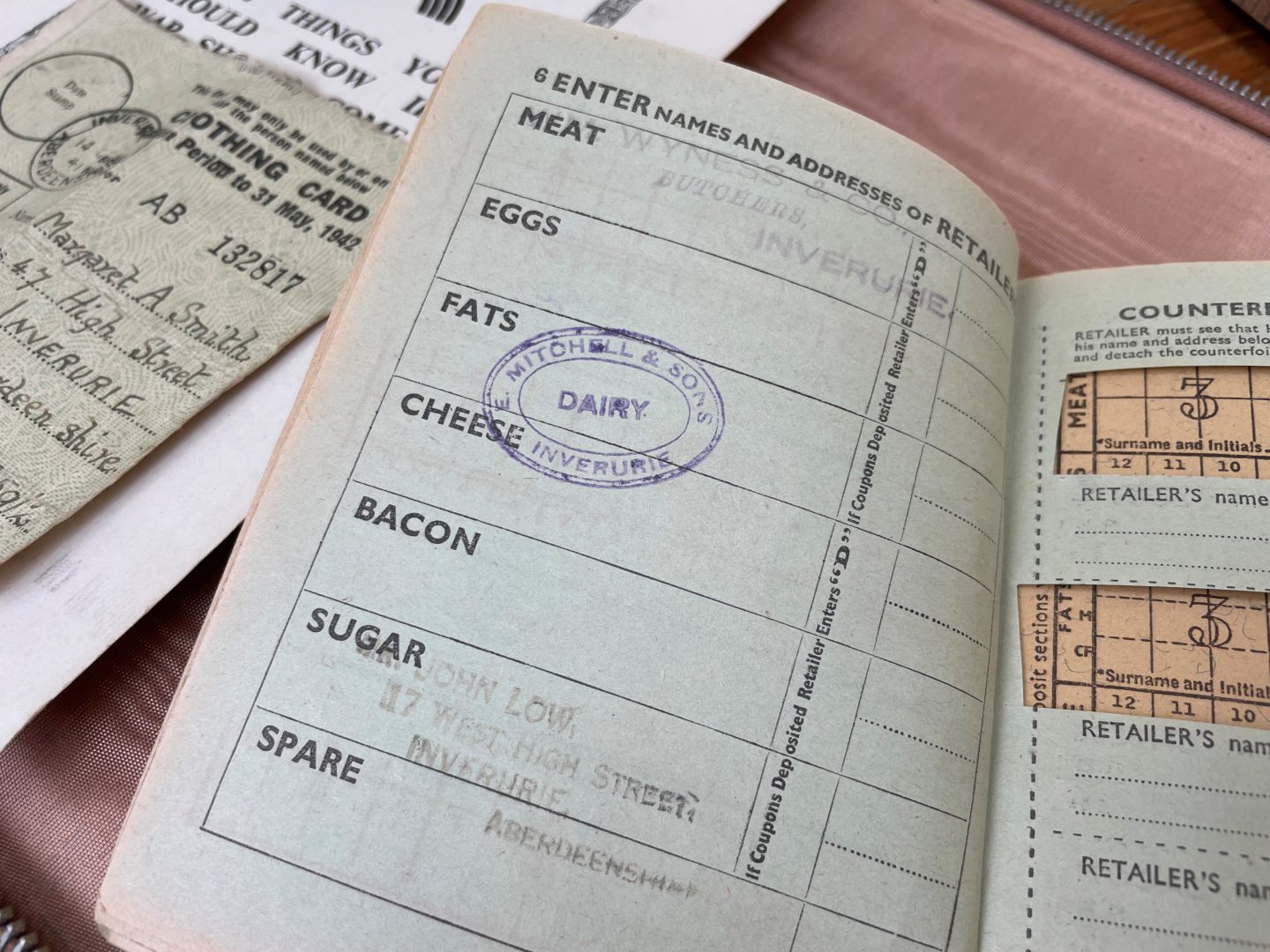

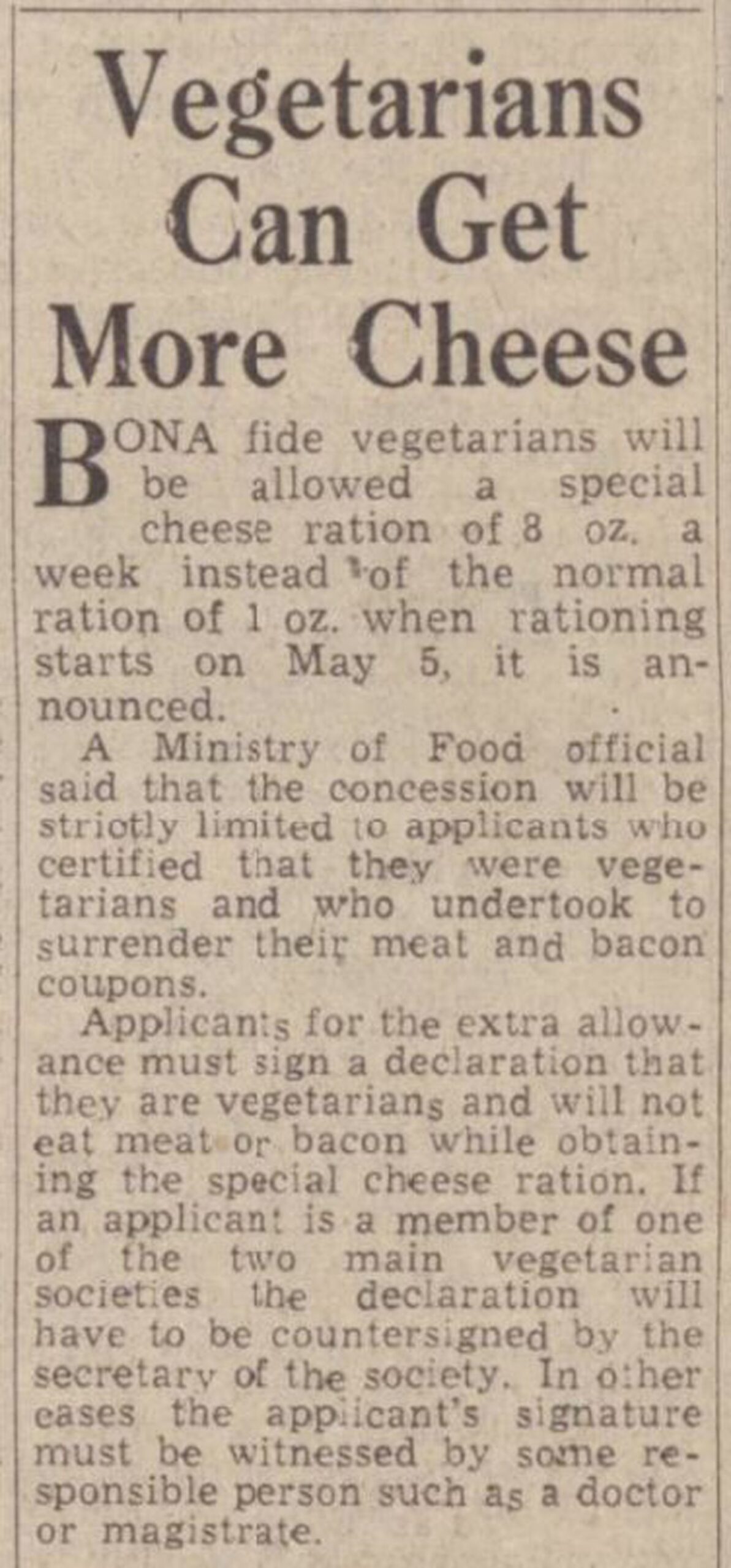

We vegetarians were issued with special ration books, but what extras did we get?

I based my week’s ration on the 1941 allowance when there were more restrictions, but as a strict vegetarian of 20 years my ration looked a little different.

Yes, vegetarians did exist back then.

Famously, War Cabinet minister Stafford Cripps was vegetarian, frugal and teetotal. And was therefore regarded as an oddball.

Instead of meat, vegetarians registered with their local food office to be issued with a special ration book.

But to stop people diddling the system for extra cheese, you had to be a bona fide vegetarian and sign a declaration countersigned by a doctor or magistrate.

They received more cheese, nuts and an extra egg a week.

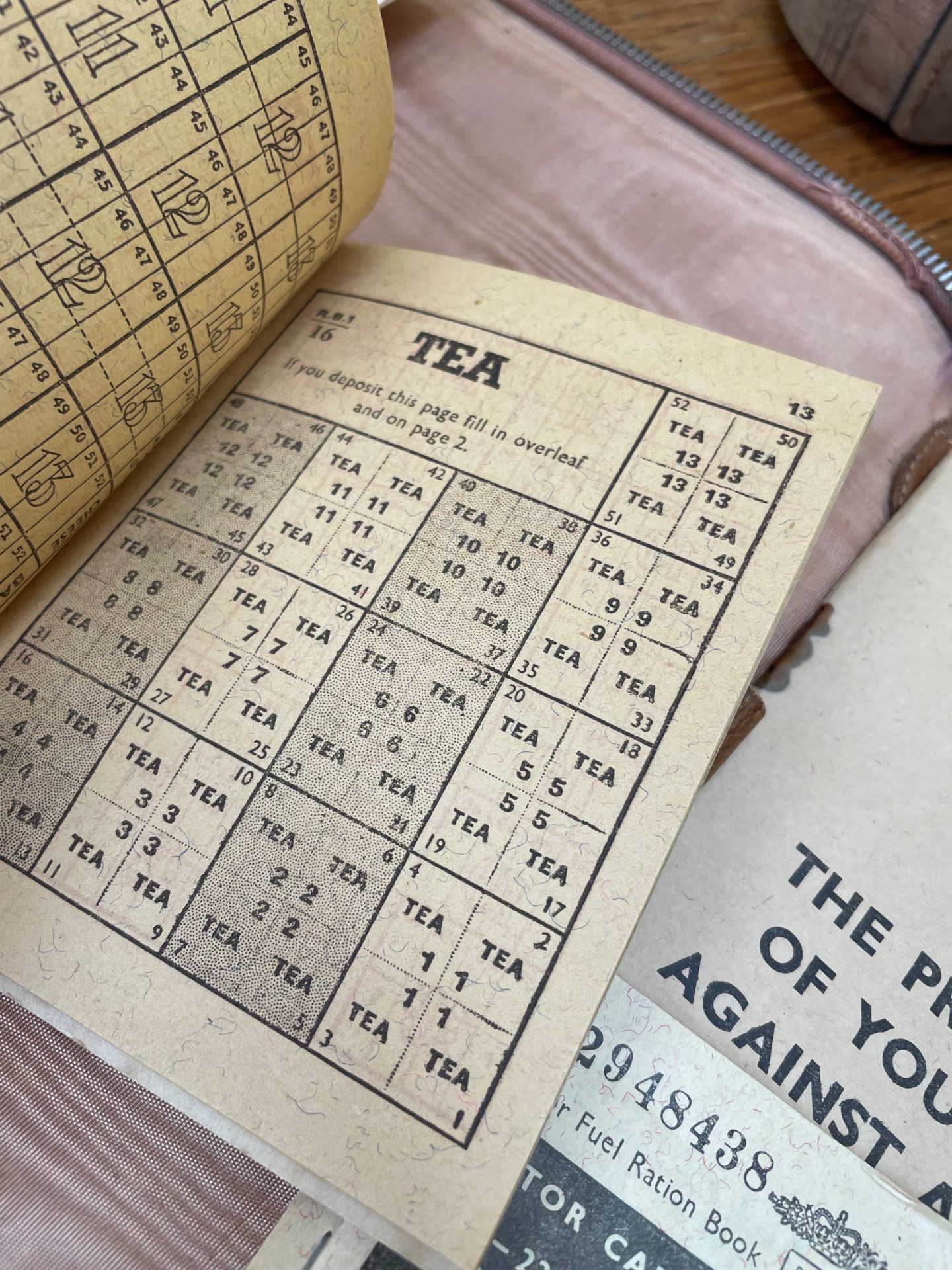

My 1941 weekly ration was: 7oz cheese, 4oz margarine; 2oz butter; 8oz sugar; 4oz jam; 2oz tea, 2oz sweets, three pints of milk, and two eggs.

Everyone got 16 coupons a month which could be used for a variety of store cupboard items, so I used my four weekly coupons on lentils and two tins of beans.

While basics like flour, oatmeal, fruit and vegetables were not rationed, food like onions could be in short supply.

And of course, people were urged to rip up their lawns, plant veg – particularly potatoes – and ‘Dig for Victory’.

With a several-cups-of-tea-a-day habit, I knew I’d struggle with only 2oz of tea leaves, which worked out at about 57g.

And I was forced to go cold turkey with my preferred, indulgent, Nigella Lawson method of double-buttering toast.

Traditional Inverurie green grocer was one-stop-shop for rations

To pick up my rations I headed to a traditional, one-stop-shop, much like the kind my wartime forebears would have shopped in.

In fact, The Green Grocer in Inverurie has been a general store since before the Second World War.

With its wood-panelled walls, traditional green shopfront with baskets of fresh fruit and vegetables outside, it’s easy to imagine people queuing there for their rations.

I was able to load up my basket and get all the fruit, vegetables, store cupboard ingredients and dairy produce I needed.

Cabbage brought back memories of school dinners… would my fussy toddlers eat it?

To make mealtimes easier, I effectively enforced a week of rationing on my husband too, and pooled two adult vegetarian rations together.

We don’t eat margarine, so in the interests of food waste I didn’t buy any, which meant I used 1oz of butter in my first wartime meal – classic bubble and squeak.

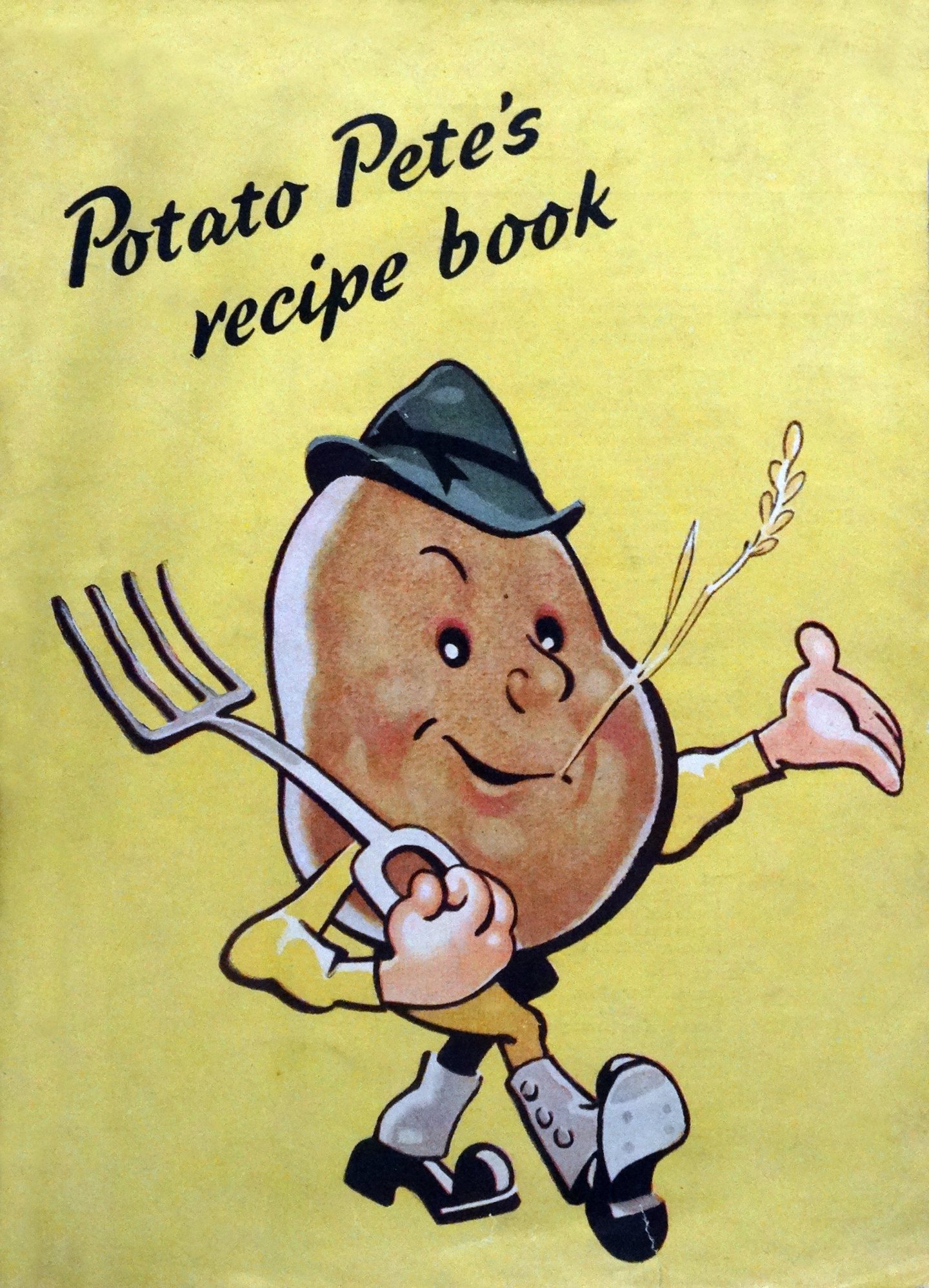

Potato Pete was the wartime marketing character devised to encourage people to get inventive and incorporate potatoes in a range of meals.

I used plenty of potatoes, some cabbage, and the recipe I followed also suggested the addition of carrot and cheese to bulk out the meal.

Cabbage is not one of my go-to vegetables. It reminds me of school dinners where it would sit in metal trays, limp and stewing in green water, and practically transparent by the time it was served.

And while the kitchen did smell like school dinners, my first ration dinner was a resounding success.

Not that my boys, aged 2 and 4, would even entertain the idea of trying it.

Luckily they had other options, but during the war this was not a luxury afforded to fussy children.

It got me thinking how life must have been for my grandma at home with two toddlers while her husband, my grandfather, James Ross, was away fighting.

He served with the Gordon Highlanders in Africa and Italy, and narrowly escaped death when the dug-out he left to collect his wages took a direct hit.

The comrades he had just sat shoulder-to-shoulder with were killed.

And his shredded wedding photos and personal effects floated down like confetti.

Grandma Peggy dodged enemy fire while shopping on George Street

Although that combat was far away, the war was very near. Grandma had a near miss herself while buying rations one day on George Street.

Suddenly German bombers appeared, strafing the street with bullets.

She recounted memories of people screaming, diving into shop doorways, and wetting themselves through sheer terror.

It’s easy to overlook Aberdeen’s war because the generation that lived through it has almost gone.

On another occasion, her father, who was a guard at Kittybrewster Railway Station dashed home during an air raid rather than using the station’s shelter.

It’s a decision that likely saved his life. The shelter took a direct hit, leaving four dead.

The city still bears the scars of the death and destruction that ordinary people witnessed while going about their ordinary lives.

And despite the trauma, they had to pick themselves up and get on with it.

Meanwhile I had the luxury of shopping, cooking and sleeping, safe in the knowledge that a bomb wasn’t going to take out my house.

How long would my week’s sweetie rations last? Well…

My first fail was eating my entire week’s sweet ration on the first evening.

While that sounds gluttonous, it works out at about half of one of those sharing bags of giant buttons, which are very easy to inhale while watching TV. Oops.

However, I surprised myself by sticking to the plan and having the resolve not to buy any more.

I’m sure many wartime children also struggled to resist eating their sweeties in one go.

The next morning I got back on track with a virtuous, but basic bowl of porridge.

Usually, I’d make it entirely with milk, but not wanting to waste a precious commodity, I made it mostly with water before topping up with milk.

It was bland, but a drizzle of honey made it palatable. Normally the cat would be boring in trying to lick the bowl afterwards, but even he turned up his nose at the watery offering.

Obtaining alcohol on the ‘black market’…

While lunch was a basic lentil soup, Friday night dinner is usually pizza.

There certainly wasn’t a lot of pizza going around Aberdeenshire in 1941.

But to soften the blow of starting the weekend on rations, I made macaroni cheese.

This was a staple my grandma made for us every Saturday, the way she had for decades before.

And at last, this was something my little boys could get on board with.

My most Googled terms that week were probably ‘what is 2oz in grams’ and ‘was alcohol rationed during the war’?

Frankly, Friday night is not complete without a glass of wine, so I was thankful it was not rationed during the war. Even during the heaviest bombing, pubs did not close.

It was felt restrictions on alcohol would be bad for morale, after all, you probably needed Dutch courage if your house had been blown to smithereens.

And let’s face it, wartime Prime Minster Churchill was fuelled by Pol Roger champagne and cigars.

Light beer was part of soldiers’ rations on the front line – they had little else to take comfort in.

While beer was freely available, other beverages were in short supply, which created a thriving ‘black market’ where spivs peddled their hard-to-come-by goods.

Luckily I was able to purchase a bottle from my local spiv: Lidl.

Digging for victory and eating seasonally is great, but not with this year’s weather

During the war, private restaurants weren’t rationed either, but food was controlled by price and no more than three courses were allowed in one sitting.

Being wealthy, as usual, had its advantages. If you could afford to eat out every day, you weren’t at home adding potatoes to every meal.

When we did eat out, I had a seasonal salad, as recommended by the Ministry of Food in wartime.

Thus in the summer everyone was encouraged to eat more lettuce, particularly as it was easy to grow themselves.

People tended to eat more seasonably then, because there were no fridges to preserve food.

Although I’m growing potatoes, carrots, onions, strawberries and courgettes in the garden, none was ready for the ration challenge due to our non-existent Springtime.

Drop scones were one of the few rationing hits with my family

Nevertheless, everything I needed was available from the local grocer, while I got eggs from my parents’ hens.

With my egg ration so far untouched, I used one to make traditional drop scones like my grandma made, served with local berries for Sunday breakfast.

Father’s Day probably wasn’t ideal for enforcing a meagre rationing diet, so pancakes for breakfast with a pot of tea was a little compensation.

And this was the only ration meal the whole household willingly ate.

I also made a loaf of bread, although it wasn’t rationed during the war.

Why?

Churchill felt doing so would be a “symbolic blow to civilian morale”.

But wheat was in short supply, so ‘National Loaf’ replaced white bread. It was produced with wholemeal flour and added vitamins – and was universally disliked.

And bread actually went on ration in 1946 when supplies were depleted after the war.

But people dutifully queued up, and there were few reports of any trouble in Aberdeen during rationing.

‘They’re dropping bombs, not sandwiches!’

Forces sweetheart Vera Lynn used to sing “keep smiling through” in the wartime song We’ll Meet Again.

And despite being confronted with war on their own doorsteps, Aberdonians still found humour on the Home Front.

My grandma recalled one air raid when a warden was shouting up the tenement stairwell for occupants to leave immediately.

One woman was stalling and the warden was told she couldn’t find her false teeth.

He gave her short shrift and shouted: “They’re dropping bombs, not sandwiches!”

With this in mind, most of my lunches were an easy, no-fuss cheese and pickle sandwich.

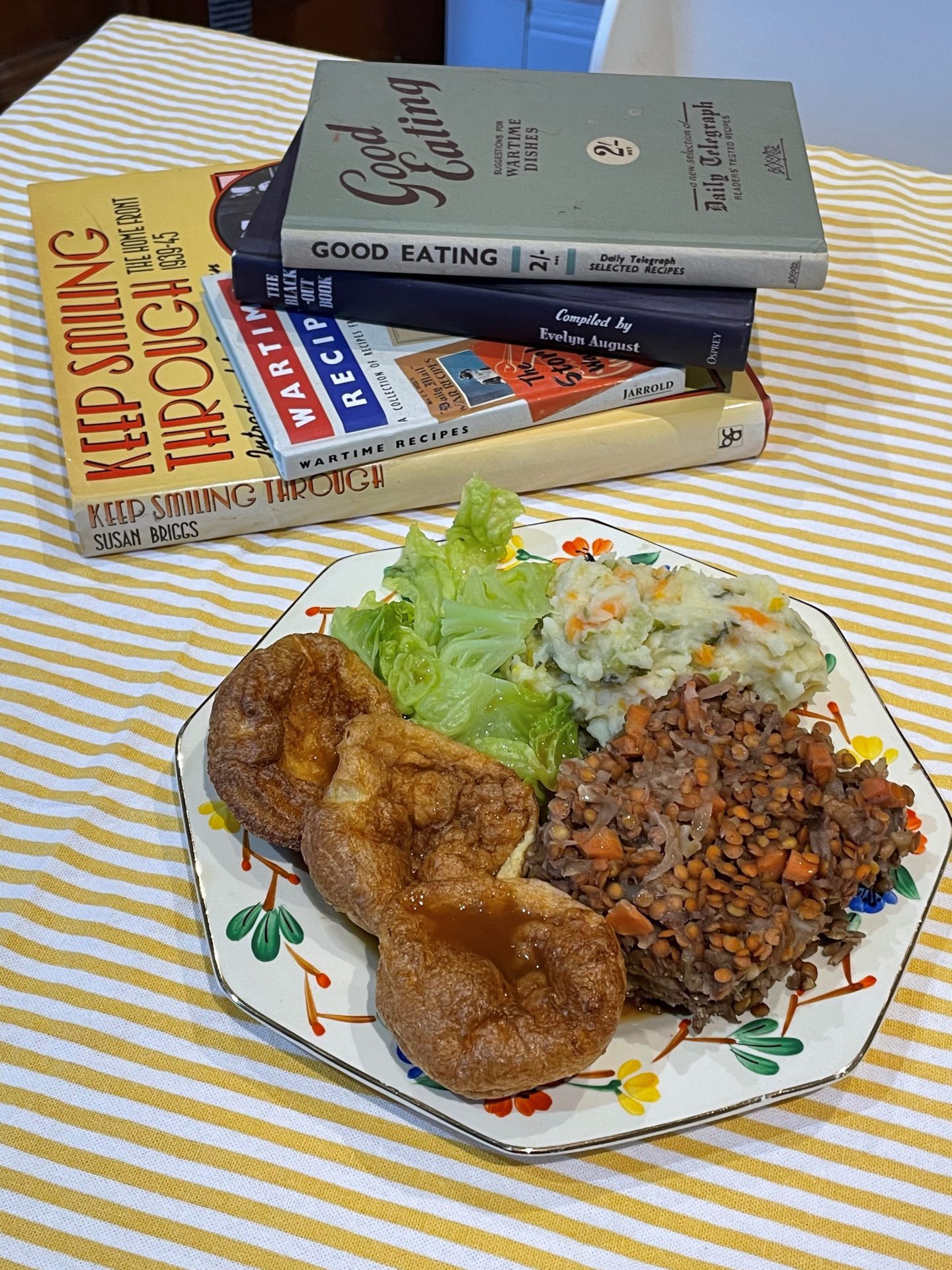

But on Father’s Day I wanted to put in a little effort, and consulted my wartime recipe books, plumping for a traditional, vegetarian roast dinner.

In 1941, adult weekly rations included 4oz of bacon and ham, and a only shilling-worth of meat, so people were encouraged to switch to vegetarian meals.

‘Surprisingly nice’ vegetarian roast dinner says my household

I decided to make a lentil, carrot, walnut and leek loaf. It looked like how you imagine disappointment would taste.

However, like most of the recipes the verdict was “surprisingly nice”.

Admittedly, the texture wasn’t great, it was dry and crumbly, but when served with gravy it was actually quite good.

The Yorkshire puddings did a lot of heavy lifting in the meal, and were well worth sacrificing an egg for. Even my two-year-old ate those.

I served the loaf with (yet more) cabbage and the leftover bubble and squeak from Thursday.

Fortunately from a wartime perspective, the loaf recipe had a high yield for few ingredients.

Unfortunately for me, it meant we’d another four portions to get through.

But wartime curry looked like the contents of a nappy

Back at work on Monday, by late morning I was reusing tea leaves to squeeze another cup out to spare my ration.

We also needed a quick dinner for two, and a night off potatoes.

I used the remaining two eggs to make a very cheesy omelette alongside the remaining baked beans and, you guessed it, lentil loaf on the side.

Thank goodness for cheese. It was my go-to snack with crackers or fruit.

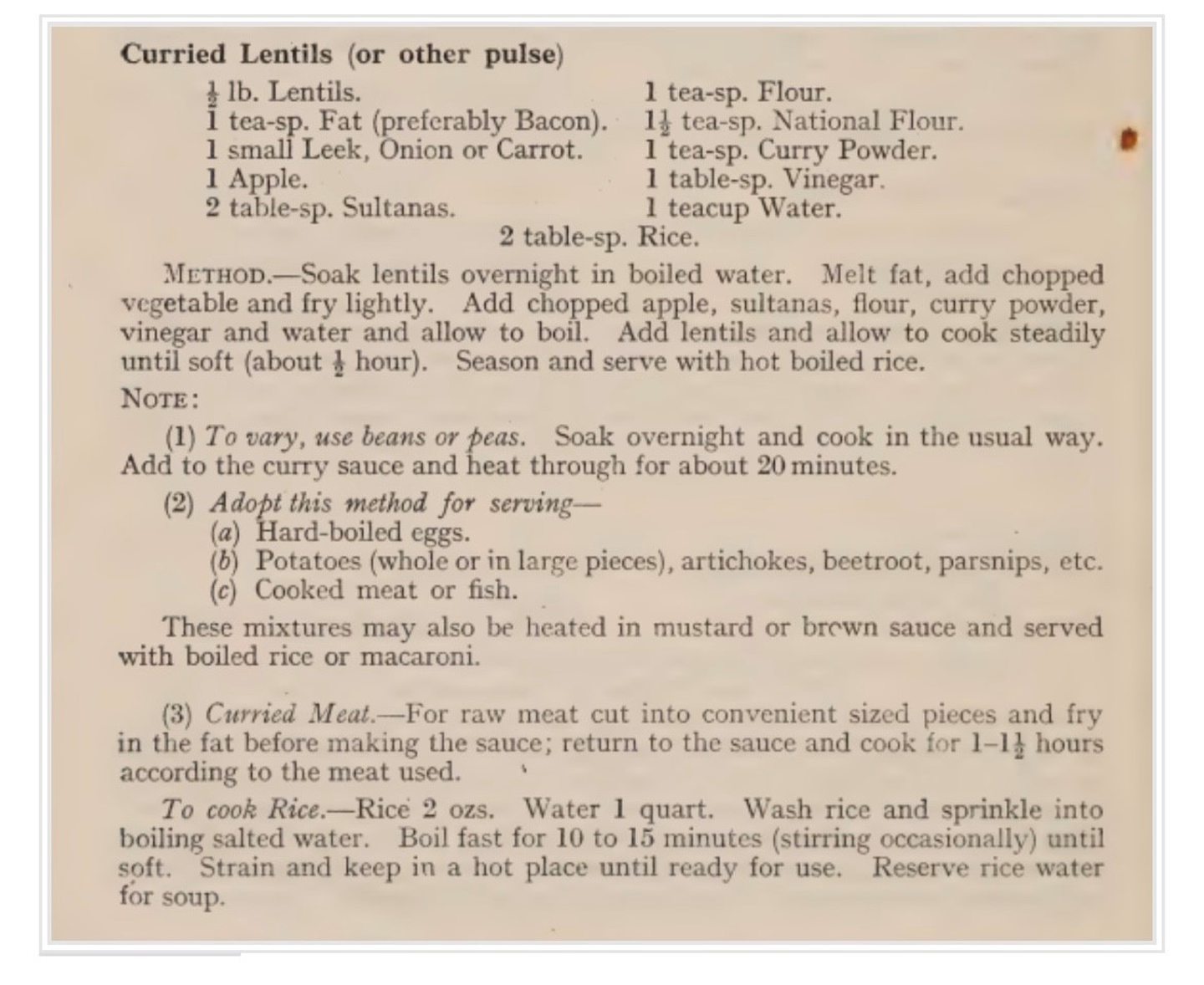

By the final day, I wanted to spice things up a bit and thought I’d have a go at wartime curry.

It was also an economical way of using up the remaining lentil loaf.

As the recipe suggested, potatoes were a great way to bulk the meal out, but I omitted the apple and sultanas.

I stuck rigidly to the basic recipe for seasonings and resisted adding additional curry spices.

But I added a lot more water to soften the baked lentils.

Of all the meals, this was the one I was least enthused about eating.

There’s no polite way of putting it, but it looked like the contents of my son’s nappy.

It’s probably not an observation I should have made aloud, but nevertheless, we tucked in.

Again, it wasn’t terrible.

It was unexciting, but as far as a filling, nutritious meal goes there were no complaints.

Finally, I understood why grandma salted everything

During the week, I quickly understood why grandma put salt on everything – the authentic wartime recipes were pretty bland.

Though I stopped short of salting my sandwiches.

Perhaps it was the placebo effect, or maybe the joy of making things from scratch, but I felt much more fulfilled by my meals.

I generally avoid ‘fake meat’ where possible, so a lot of my diet is already based on pulses and beans.

However, I was eating bigger portions of protein and more vegetables than usual.

I found that I didn’t need – or want – to reach for sugary snacks in the evening as I was still full from dinner.

These were the kinds of meals that had to sustain a manual workforce through long hours – from factory workers to Land Girls to railway staff.

Rationing did highlight a divide between countryfolk and city-dwellers; the former were likely to have bigger gardens for crops or keeping hens.

But overall the population was healthier. Regardless of social class, everyone had equal access to nutritious, balanced food.

So, after a week of it, what have I learned from living on wartime rations?

I admit I used some of my husband’s tea ration, and every time I was offered a cuppa out and about, I took it.

Although I resisted filling my pockets with biscuits at an event when reporting for the P&J.

While I hope never to eat a wartime curry again, and all the food was rather brown, there are elements of the rationing that I will continue.

It’s much easier to hit your five-a-day with a side dish of bubble and squeak, and it forced me to be much more organised with budgeting and meal planning.

I found even more respect for the 1940s housewives who balanced the rations with children, war work, housework, and often with no husband at home to help.

But I’m not sure I could ever commit to 2oz of chocolate a week.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation