With the Atlantic almost knocking at her door, wind spiralling around her cottage, sheep and cattle needing to be fed, peats needing to be cut and a heap of ministry forms to fill— Ena MacDonald knows the true meaning of the word crofting.

Now in her ninth decade, she’s lived and breathed for her family croft in the Outer Hebrides since her birth there in 1940.

Her home is yards from an often turbulent sea, nothing much between her and North America.

Apart from ten years as a young woman working in Glasgow and Australia, Ena has been the very soul of Ardbhan at Kyles on the west side of North Uist since 1966.

She has carved an exalted place for herself in crofting history despite the early handicap of being a young, attractive woman in a very traditional man’s world.

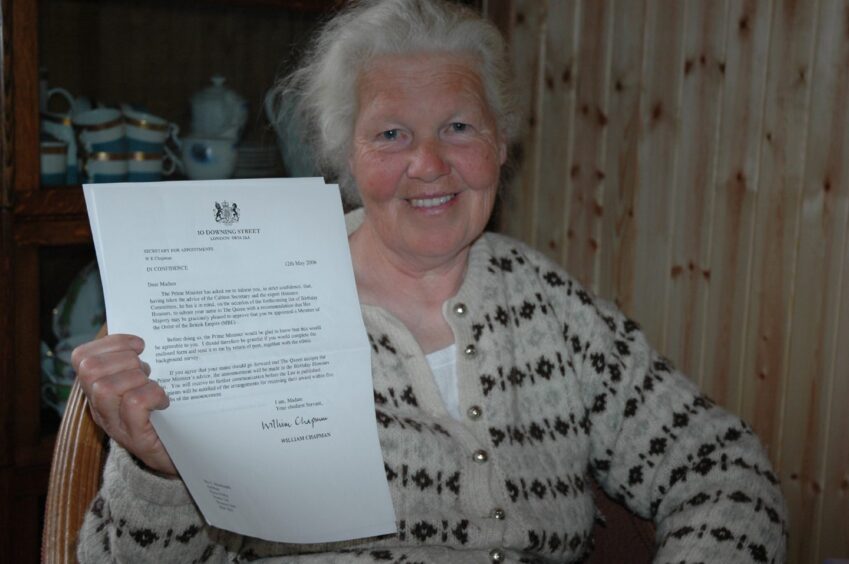

Made an MBE for her services to crofting and to her North Uist community, Ena has earned the status of legend both locally and much further afield.

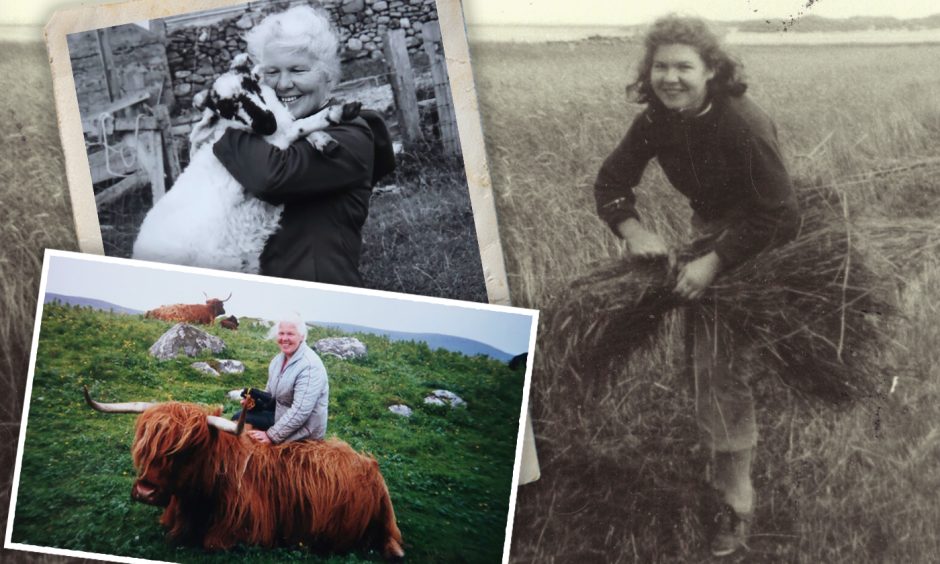

She’s highly respected in the world of Highland cattle with the pure bred herd she started in the 70s, and went on to run with her son, Angus.

Although at 84 she has some health issues and no longer works hands-on with the cattle, Ena is still involved with the successful running of the croft.

Nowadays, most crofters have a ‘real’ job, or several, to help pay their way.

But for the first few decades of Ena’s life, the unforgiving work of a crofter was the only way to put food on the table and pay the bills.

Each season had its own character, and brought with it its own set of challenges.

In this article, Ena takes us through what life was like in each of the four seasons as a Hebridean crofter, starting with…

Autumn

Autumn was a busy season, with all hands to the pump to bring the harvest ‘corn’ in.

Corn in Uist is a mixture of oats, rye and barley unique to the Uists.

Up to the 1950s and the advent of tractors, it was cut by hand, with a scythe.

It was hand-forked to dry it, and then tied into sheaves, again by hand until the reaper-binder machines came in.

Ena said: “It was tied into bundles of six, and left to dry for 10 more days before being made into ricks of about 22 sheaves.

“Then the ricks were piled high into carts and the horse brought the cart into yard close to the house where it was made into big stacks, with 10 ricks to a stack.

“I remember sitting high on top of ricks in the moonlight, after a long day.

“The stacks were tied down with rope, we didn’t even have nets at the time.

“They had to be really well secured against the wind.

“I remember one year the sea was high one night and a lot of the stacks got broken up and flew away to the neighbouring island of Ardheiskeir.

“But there was a feeling of real satisfaction when you had brought the corn home and secured it well for the winter.”

Winter

Winter was also a hard-working season.

The cattle were overwintered in the byre, and fed from December to May on the corn grown on the croft in the summer.

Ena said: “We used seaweed as fertilizer, and brought it back from the beach in cart loads.

“The potatoes were fertilized with seaweed as well as the corn.

“Any cow that wouldn’t get through the winter was slaughtered and shared among the whole community.

“We had no fridges, and not even a mincer, so it was salted and nothing was wasted.”

When the time came to slaughter a sheep, the intestines were taken to the sea and washed thoroughly before being steeped in salt.

“They were lovely and clean and white,” Ena remembers. “We kept the blood so we made black and white puddings in the intestines, adding nothing more than oatmeal, onion and salt and pepper.

“I remember some people stowed their puddings in chests full of oatmeal.”

Ena pauses to think about her mother, keeping the farm going during the Second World War when the men were away.

She said: “It was hard on the women, I remember my mother working, working, working.

“One time they had killed a cow and she had to deal with the intestines.

“She said, ‘Oh my goodness, I wish a fairy would come and give me a hand’, and suddenly there was a figure looming in the doorway.

“It was her sister who had arrived unannounced from Mull by bike.”

Spring

Calving and lambing would start in April.

When a ewe died or rejected her lamb, it fell to Ena to raise them as pet lambs by the warmth of her Rayburn.

This photo of Ena with her pet lamb Maradona captures the love she feels for all her animals.

She said: “It was 1986, and Maradona was making the news in the World Cup, so I called this pet lamb after him. I’d never heard of Maradona before.”

Ena remembers lambing as a safer time than now.

She said: “The sheep were outside and there were no predators. Nowadays there are sea eagles and lots of ravens. Then we only had a few crows.”

At its peak, Ena’s flock was 50 blackface sheep and a ram.

She dispensed with the sheep in the late 80s, as her mother was frail and she couldn’t give either the attention they needed.

Spring was also the time to plough.

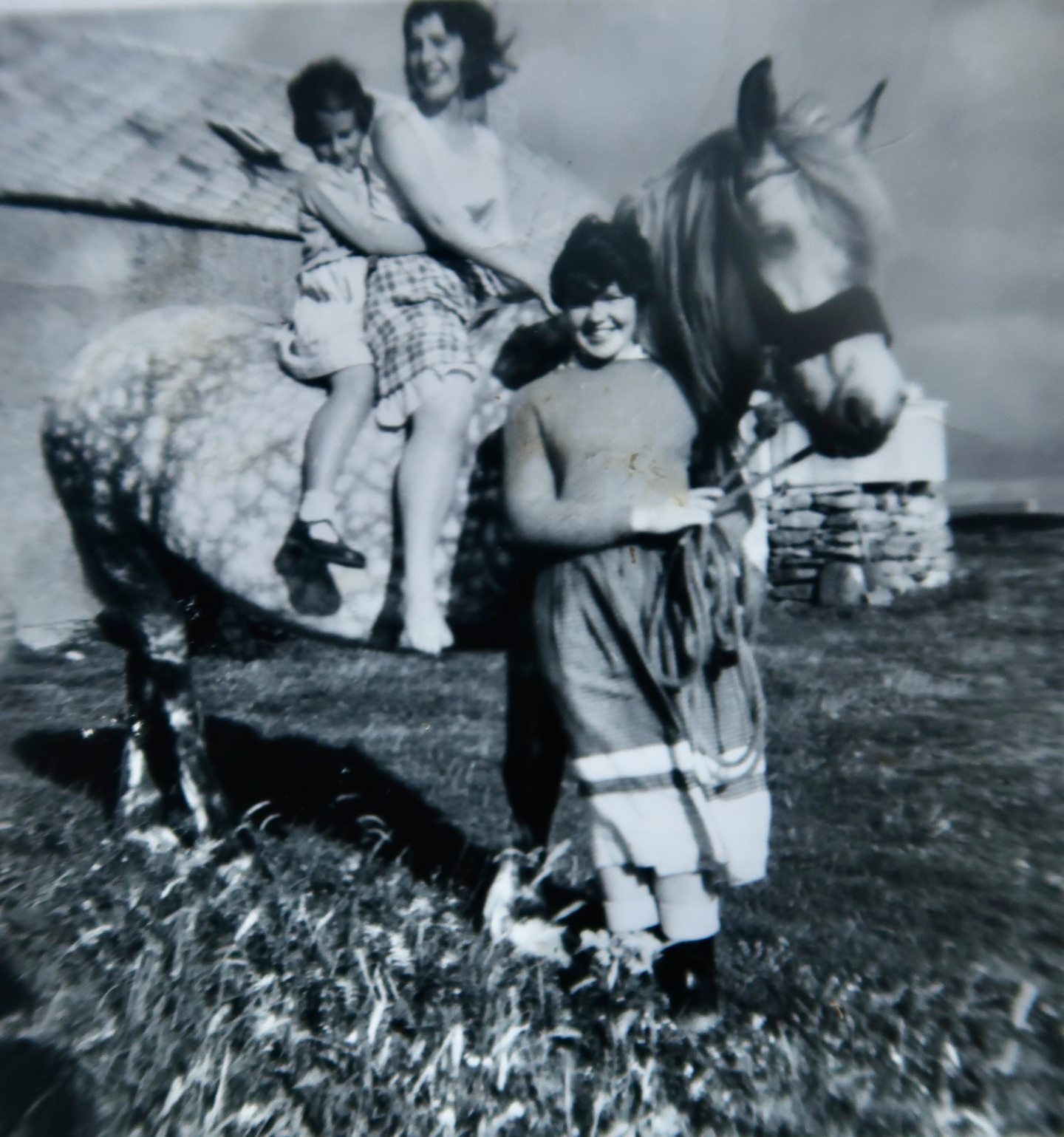

In those days it was by horse with a single furrow, the carefully saved corn seed broadcast by hand over the field.

Summer

Summer was the time for lifting peats, a process which started in May.

The North Uist peat bogs are quite a distance inland from Ardbhan, and the family would head out on foot with their peat iron.

It meant crossing a tidal bay, at considerable risk.

She writes: “One day during the war our mother was going to cross the bay with the five of us [Ena and her siblings].

“She left a few minutes too early pushing the pram with me in it and the other four holding hands across the outgoing tide.

“My sister Agnes, a four year old, started to panic and wouldn’t move a step.

“Poor mother couldn’t let the pram go or it would float away so she screamed at my brother Ewen to grab and drag his sister across.

“He seemed rooted to the seabed and it seemed like hours to realise that he was able to help.

“Had she gone too far to the right, the sea was deeper and the current would have lifted her.”

Cutting peats was hard, involving seven visits across the bay to bog at different stages.

In summer the work was made bearable at tea time with a picnic of scones with homemade butter, cheese, crowdie or eggs.

Ena said: “First the peat was cut and when it was slightly dry, we went back to put it into rows.

“Once it was dry, we took up the horse and cart and carried the peats over to load in.

“You couldn’t bring the horse and cart onto the uneven bog.

“Tractors made it so much easier.”

There were times when there wasn’t enough peat for the winter, and everyone had to scour the beaches for driftwood.

In those days, there were no fences on the island, so everyone’s cattle grazed together.

Ena said: “In every village a herdsman was paid to look after them. He brought them into the cattle fold at night, and then let them out about 6am to graze.

“At 9am he would bring them back in again, and the women, and sometimes the men, would come down and milk their own cows.”

Some crofts had a dairy near the house, kept spick and span for butter and cheese-making.

Ena said: “We made delicious crowdie from the cream when the milk soured in the summer.

“The skim milk would be used for cheese, and the whey for baking.

“We had no fridges. Some people had a cold cupboard outside with a thatched roof which they used for storage, which would make things keep for around a week.”

Children played their part in the household from a very early age.

They carried water from the well, helped till the land, planted potatoes and were generally expected to be useful wherever they could.

Ena writes: “Children [now] are not getting involved in croft work, nor are they taught where their food comes from. The opportunity isn’t there for them because now everything is mechanised.

What about holidays and Christmas?

“Nowadays people have other jobs, they have holidays, we never knew the meaning of holiday, my parents never had one.”

From the outside, it seems a hard life, with very little cash to splash.

Ena said: “But we were all in the same boat, all without money.

“As children, we never heard of pocket money. If someone from the mainland came and gave us a 2 shilling piece we would put it in an old cocoa tin.

“Whatever people gave us we handed to our parents.”

There was never a Christmas dinner, Ena adds.

“As children we used to love seeing photos in newspapers, or cartoons like The Broons, sitting at the table, or Desperate Dan with a huge cow pie, we never thought other people were enjoying this kind of life.

“We just accepted it. We weren’t jealous.”

Fortunately, since 2006 Ena has been documenting her crofting life and all its challenges and changes in a regular column in the local paper.

You might also enjoy this article about crofting:

West Highland crofter of 17 years says traditional way of life has disappeared