Imagine a train travelling from Aberdeen Harbour, through the streets of the Granite City via Ferryhill, Great Western Road, Hazlehead, Westhill, and ending up in Echt?

If it wasn’t for the advent of the bus, and some 19th century Aberdonians who didn’t fancy trains of livestock trundling past their mansions, this could have been a reality.

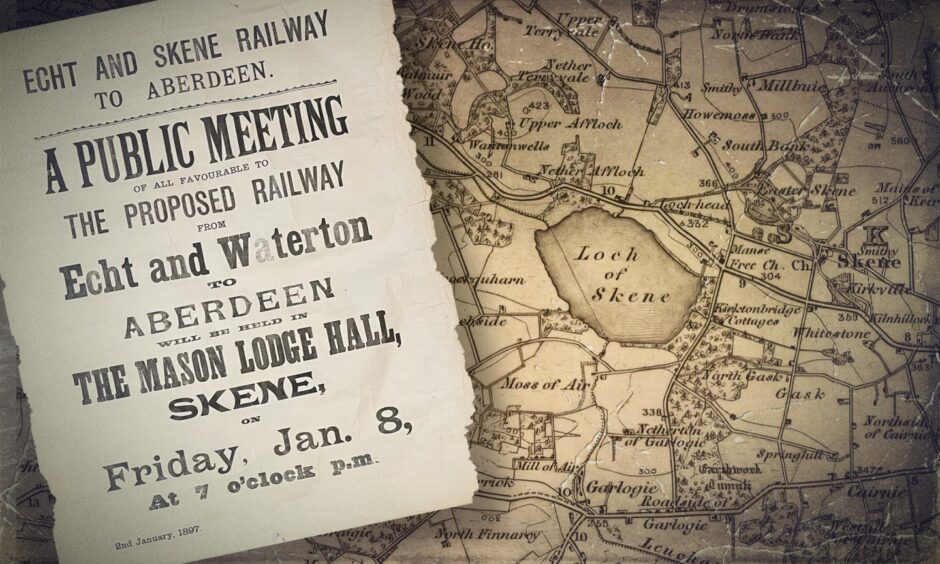

I knew of the long-abandoned proposals for the Echt and Skene Railway, but it wasn’t until an antique shop discovery on holiday I found evidence of its planning.

And that evidence was a faded advertising poster, hidden away in an antiques shop at Knaresborough Station, North Yorkshire.

This old poster has long outlived the people and plans behind the railway, a ghost of what might have been.

At a time when the reopening of long-gone lines is a hot topic, the Echt and Skene Railway is not so much a lost line, more of a lost opportunity for the growing communities of western Aberdeen, Kingswells, Westhill and beyond.

It was initially proposed as a rural railway to boost agriculture.

While a line might not be needed for cattle these days, a suburban route linking Aberdeen to Westhill would be well-used by modern commuters, going by the volume of traffic you see on the roads between the two.

Read on for the story of the railway that nearly was,

- The routes it would have taken through the city and shire,

- And why it was never built…

How cheap imported American wheat almost gave Skene a railway station

Prior to the Light Railways Act of 1896, railway companies had to apply for a specific act at Parliament to enable them to progress with plans to build a new railway.

This was costly, both in terms of money and time.

But the government was keen to encourage railways into rural areas.

Agriculture suffered particularly badly from a depression the 1880s when the British market was flooded by imported, American prairie wheat.

Despite consecutive years of bad harvests in Britain – which would ordinarily push up wheat prices – farmers were being undercut by the American market.

The decline in cereal prices lead to less land being cultivated for wheat, and an exodus of workers from the country to cities.

Therefore, the new light railways act was a government attempt to stem rural depopulation by making it easier for farmers to transport goods more widely.

New legislation enabled light railway from Aberdeen to Blackdog

The legislation enabled low-cost, light railways to be built in country communities where population had been in decline.

More substantial than tramways, they were less costly and sizeable than standard railways.

They also did not need to have the same infrastructure as normal railways – there was little to no signaling required.

In Aberdeenshire, several potential routes were quickly identified.

Among those built included the Strabathie Light Railway from Aberdeen to brickworks at Blackdog in 1899, and the Fraserburgh to St Combs Light Railway in 1903.

An unusual feature of the St Combs route was that the locomotives were fitted with cowcatchers to deflect obstacles off the track, because much of the line was unfenced.

But a flurry of other lines were proposed including a light steam railway from Aberdeen-Newburgh-Peterhead, and a 17-mile railway from Aberdeen to Echt and Skene.

Rival companies made bids for railway to Echt and Dunecht

It was hoped the Peterhead scheme would enable granite to be transported to Waterloo Quay in Aberdeen, with stops in coastal communities like Collieston and Slains.

But that scheme, and others, didn’t amount to anything.

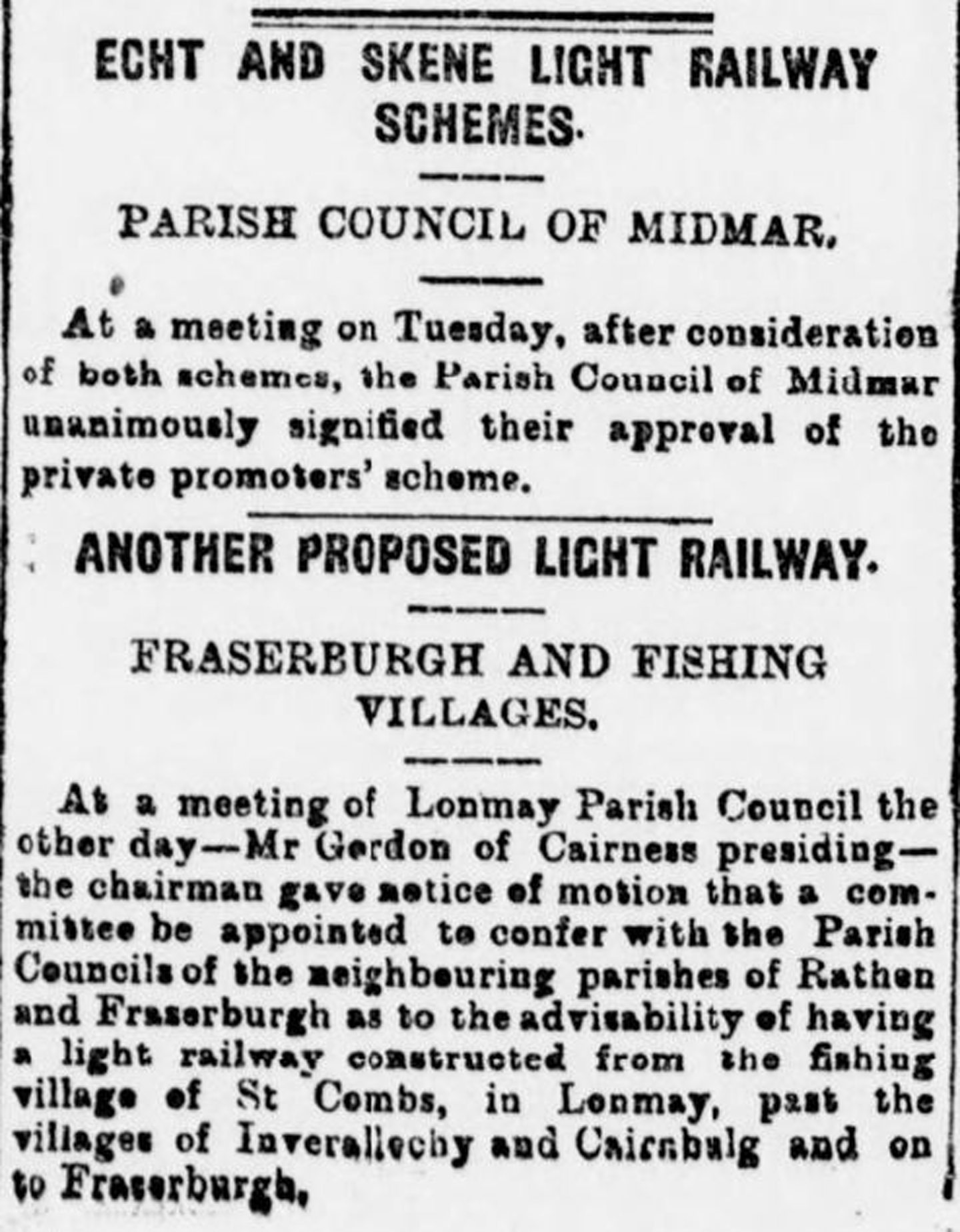

Meanwhile, in November 1896, two rival companies put in bids for the Echt railway – one for a steam line and another for an electric railway.

The Press and Journal reported how the two light railway schemes had “given the liveliest satisfaction in the Skene and Echt districts and also in the city”.

There had been talk of railways in the area for nearly 20 years, but in 1896 the two companies set out serious bids.

It would have its own trackbed from Echt to the city, but from there use existing rails and roads.

Echt railway route would have followed Straik Road through Westhill

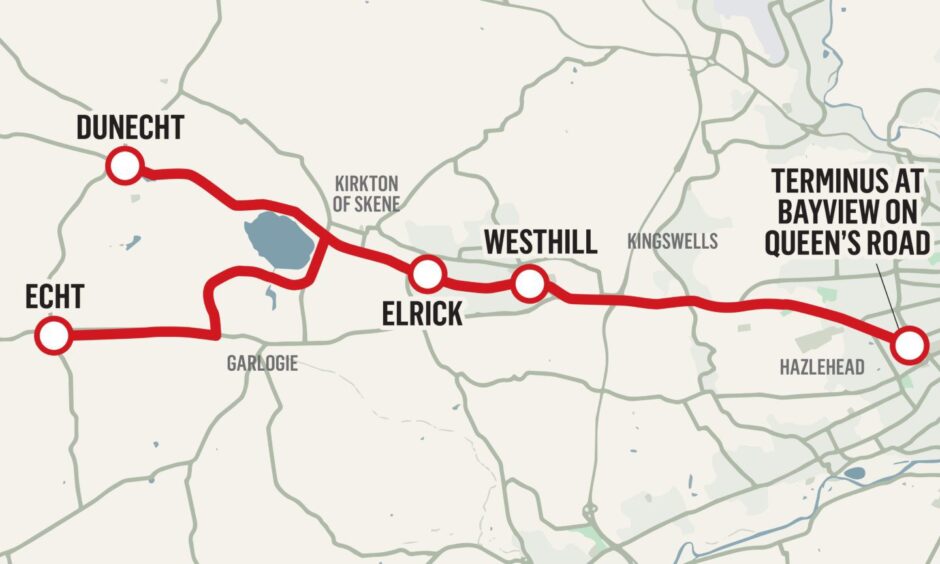

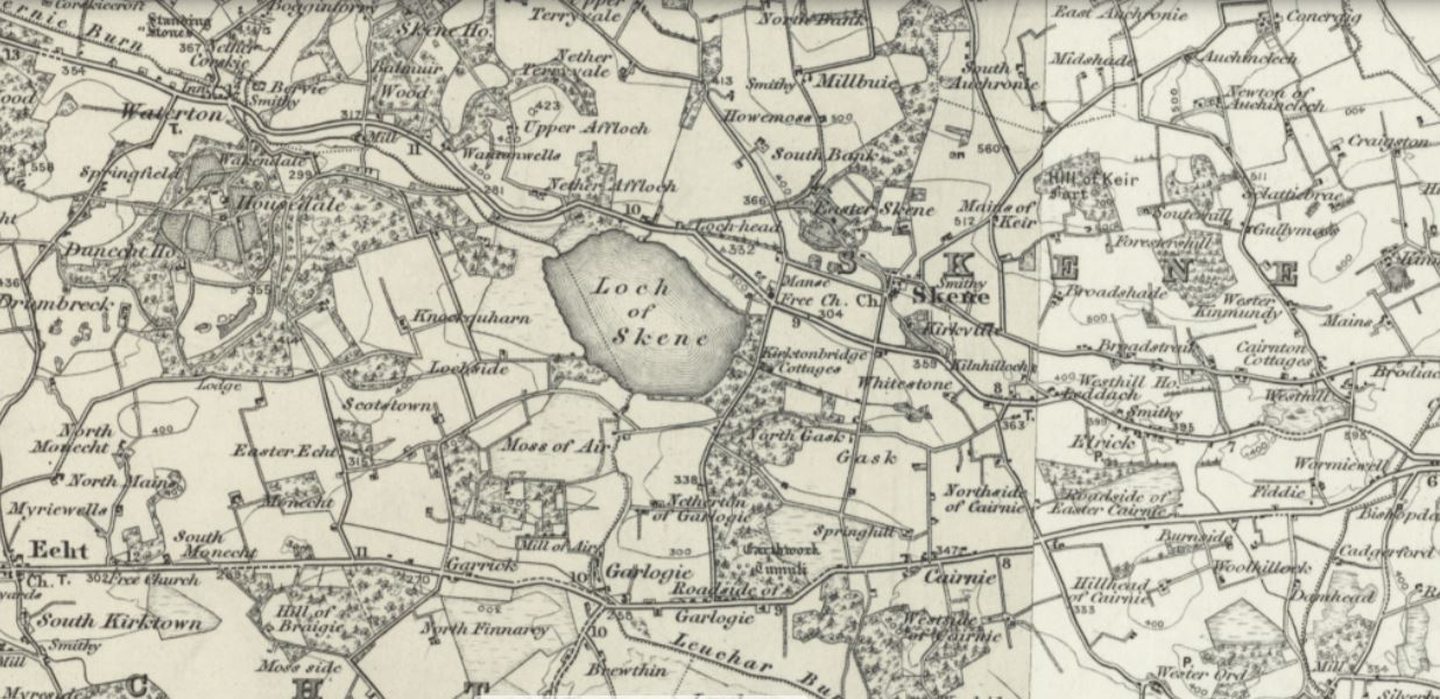

Messrs Macqueen and Knox proposed a steam railway from Echt to a point north-west of the Loch of Skene. There, it would meet a branch from Waterton – the old name for Dunecht.

The railway would continue along the north bank of the loch, almost parallel to the modern-day A944 Straik Road through Elrick and Westhill.

It would then cross the road at what is now Arnhall Nature Reserve in Westhill, then continue alongside the north of the A944 to the city boundary.

From there it would proceed to the city tramway terminus at Bayview on Queen’s Road.

And then things got a little more convoluted.

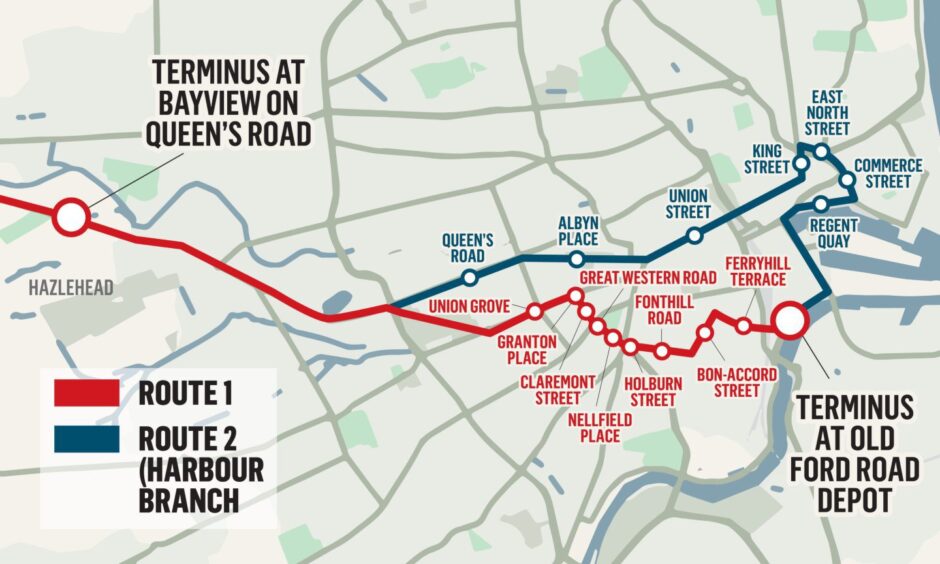

The promoters sought “running powers over the tramway lines” along Queen’s Road, Albyn Place, Union Street and King Street as far as East North Street.

It was proposed a railway would then be constructed along East North Street and Commerce Street to Regent Quay, where it would join the harbour rails.

Goods trains would travel through Aberdeen’s West End to harbour

Effectively people – and more importantly – goods could travel directly from the farms of Dunecht to the harbour.

From the harbour, the Echt Railway would continue to South Market Street and turn onto the Esplanade to a depot at Old Ford Road.

Meanwhile, a second branch line would go from the Bayview Queen’s Road Terminus south, across what is now the Harlaw pitches, along Union Grove and Granton Place, before crossing Claremont Street.

The line would have continued through a yard there, across Great Western Road and down Nellfield Place.

From there it would cross Holburn Street to Fonthill Road, then up Bon-Accord Street as far as Ferryhill Terrace.

At this point it would cut through Dee Village and terminate at the proposed Old Ford Road depot.

GNSR proposed a route from Culter to Echt

The second proposal for the Echt Railway came from the Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR), and its route was different.

GNSR proposed a rural railway which would commence from the Bayview depot, but travel via Newhills, Peterculter, Skene and Echt before terminating at Kirktown of Echt.

Both proposals were heavily opposed by Aberdeen Corporation, which ran the city’s tramways.

The private scheme, which would take passengers to Dunecht, was backed by the Parish Council of Midmar.

But ultimately, it was dropped because nobody living in the attractive West End villas wanted goods wagons clattering past their homes.

The GNSR route was favoured because it utilised existing tramways, and could link to its station at Kittybrewster.

But the costs were too great, and it too was abandoned when Aberdeen Corporation bought Aberdeen District Tramways in 1898.

Fury when Echt and Skene railway scheme failed again

But the move was met with fury from rural residents.

One wrote to the P&J condemning GNSR for their “unaccountable” action of quietly dropping their order for “this much-needed railway”.

The man accused GNSR of taking the Skene and Echt railway “out of the hands” of Mr Macqueen and his private syndicate.

He suggested they didn’t want the railway, they just didn’t want anybody else to have it.

The reader added: “One of the most populous agricultural districts of Aberdeenshire is once more disappointed.”

By the turn of the century, there was still a desire to see Echt railway come to fruition.

Another plan was put forward, this time by the then-Aberdeenshire Council.

The proposed Skene and Echt Light Railway would see a roadside line from the city boundary and Woodend to Echt.

It would also have a branch line to Dunecht, and costs were sought for both steam-powered and electric locomotives.

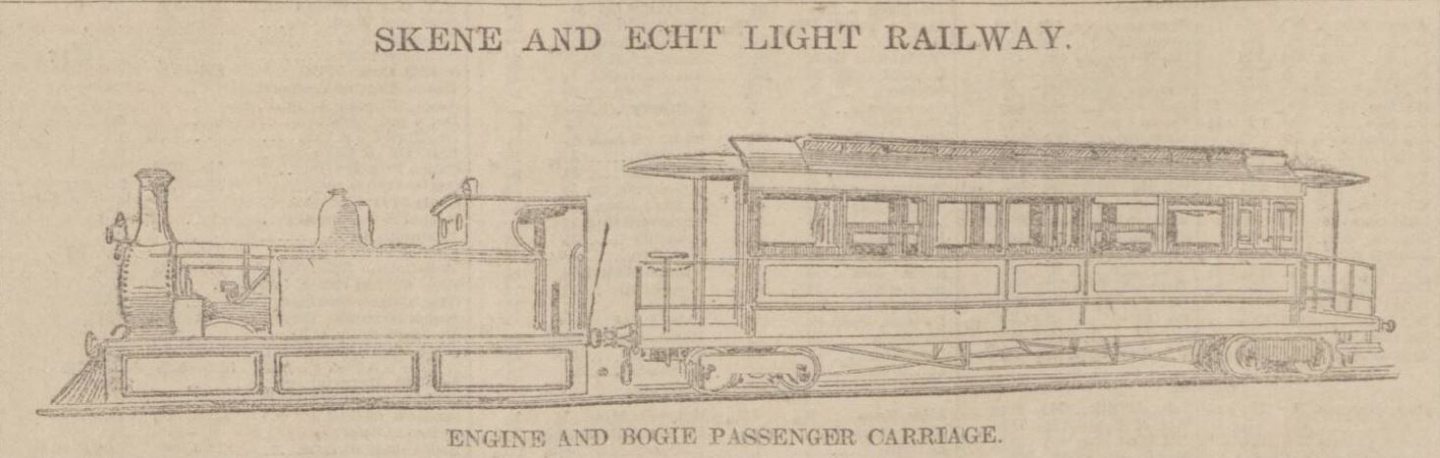

Tram-like carriages for Echt railway

A report in the P&J in January 1902 said: “The necessity for a light railway from Aberdeen to Echt district has long been recognised, and it is believed that, if properly managed, it might be made a very good paying concern.”

The locomotive deeded most suitable was a six-wheel, coupled-tank type, similar to those used on Irish light railways.

The passenger car would have provision for third and first class, and carry 40 travellers.

While the good waggons would carry five tonnes, the company also said it would procure cattle trucks and brake vans.

And “steam wagons similar to those used on the continent” would be used for “increased passenger traffic, weekends or holidays”.

Buses proved death knell for light railways and trams

But once again, the costs relating to laying mixed-gauge track saw these plans shelved.

And by 1905, the GNSR motorbus – which would ultimately be the death knell for Aberdeen’s tramways – arrived in the district.

GNSR launched motor buses to link stations to communities where railways didn’t exist, like Ballater to Braemar.

From June 1905, it began running buses from Culter to Dunecht. A direct service from Dunecht to Schoolhill Station was introduced the following year.

GNSR finally admitted a line to Echt wouldn’t pay, but by 1928 they had also withdrawn the bus services.

It was also the beginning of the end of Aberdeen’s tramways, so any lingering hopes of a light railway went up in smoke.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation