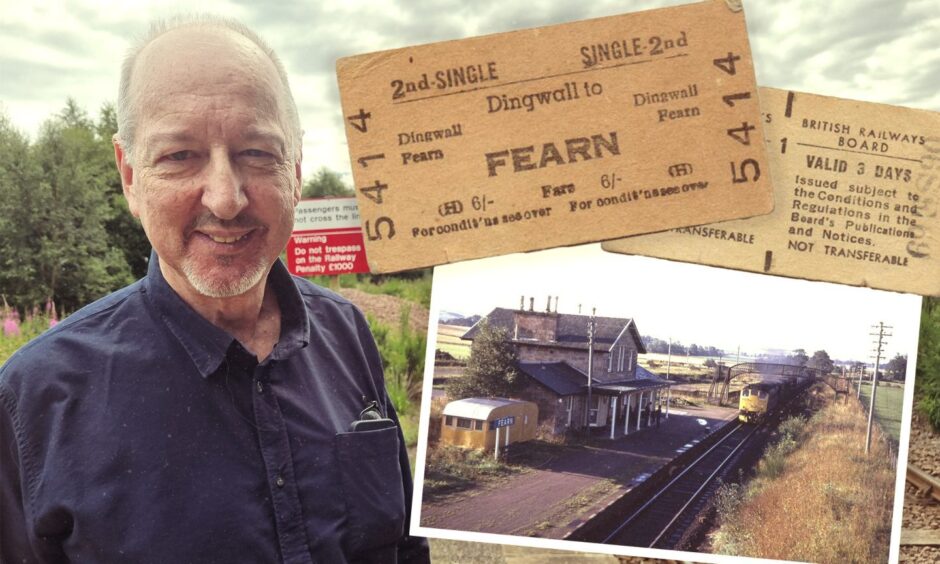

Mark Nolan was a callow youth 50 years ago, just out of school with no idea what he wanted to do with his life.

From Kingston-upon-Thames, he had been coming to Easter Ross on holiday for years, so “it seemed the natural place to go after leaving school,” he says.

Someone tipped him off that he had to register for a National Insurance number, so he headed for the Invergordon Labour Exchange to seek one out.

A little later, the teen found himself with more than he bargained for.

The keys to Fearn station on the Far North were jangling in his pocket, and he was in a self-confessed ‘state of mild shock’.

For the next year, he ran the station single-handed, selling tickets, dealing with parcels and freight for the princely sum of £21 a week.

Mark puts his meteoric rise from feckless youth to rookie railman down to Ross-shire’s oil boom.

How Mark got the job despite the odds

“In 1974 people were earning unprecedented wages building oil drilling platforms for Highlands Fabricators at Nigg.

“The traditional labour force was decimated, to the extent that farm workers, shop assistants, milkmen and postmen were in short supply.

“Not surprising when they could earn four times as much at Nigg.”

After a prickly interview with the Invergordon area manager, clearly unimpressed by the long-haired hippy-style youth before him, Mark’s duties were established in an atmosphere of mutual dislike.

“I could tell he didn’t really want to give me the job,” Mark said. “If it hadn’t been for the labour shortage I’d never have got through the door.”

Mark defied the manager’s dire predictions and did in fact turn up for work ‘at stupid o clock’ on a freezing February morning.

Dick, a kindly clerk from Invergordon showed him the ropes—ticket selling, meeting trains, receiving parcels, weekly accounting, and more ominously as it turned out, dealing with the potato traffic.

But the most important instruction came the minute Mark walked into the ticket office, when he was shown the electric fire, and told on no account to turn it off, ever.

He said: “Prominently displayed on the wall was the Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963 which stated that in a room where severe physical effort was not involved, a temperature of less than 16 degrees Celsius shall not be deemed to be a reasonable temperature.

The ticket office was freezing

“It’s quite possible the room would never have gone back to 16 degrees if it had been turned off.

“For my part I made sure I never did anything in the ticket office involving severe physical effort.”

With three passenger services daily except Sundays each way between Inverness and Wick/Thurso, Mark’s duties were far from onerous.

Parcels would be discharged onto the platform off the early train, which Mark would move to a wire cage in the station for onward delivery.

A few months into the job, a friend turned up in a decrepit Post Office van.

It turned out he had won the tender to deliver the parcels locally, but hadn’t a clue where any of the places were.

No problem in the relaxed Highlands of the 70s.

Mark simply closed the station, zipped around the Fearn peninsula with his friend delivering parcels, making sure to be back in time for the afternoon train.

“We nearly always made it back in time for the train, and as far as I know no-one ever noticed when the station was closed.”

The Area Manager might have had something to say about this, but he never found out.

“By current standards, there were a lot of problems with gung ho arrangements like this,” Mark says.

“Would I have been insured in the event of an accident? Did the delivery van even have insurance or an MOT?

“But it was the 70s. For better or worse it was a much simpler time.”

There were perks in the job, albeit unofficial.

Mark turns his hand to bacon sandwiches

Alec, the buffet car attendant on the early passenger service, used to leave Mark a cup of tea on the platform without fail.

Mark returned the favour by working out that the only thing Alec couldn’t do in the buffet car was fry bacon.

“This led to feverish preparation and a miracle of timing. By pre-heating the frying pan, lining everything up and listening for the train whistle at Nigg Station crossing, I was able to hit Alec with a hot bacon and egg toasted sandwich just as the train arrived.”

And then there was the accommodation situation.

The flat above the station had already been rented out to a tenant.

Another relaxed solution was found.

At the suggestion of Dick, the benign Invergordon clerk, Mark bought a caravan from a friend, and it was tucked away on a plot of land on the platform, between the station building and road bridge.

“My caravan would never have been allowed anywhere near the railway property today, let alone on the platform.”

And as for Mark moving into the warm kitchenette to sleep over the coldest months- “no chance nowadays”, says Mark.

Fearn station first opened in 1864

Originally Fearn had a second platform and a loop for trains to pass.

This complexity was serviced by signals, a signal box and a full complement of qualified staff.

By the time Mark came along, the second platform and the loop had been decommissioned, and he was in sole charge.

He said: “However there was still a goods yard with two sidings and a loading platform.

“The reason why Fearn station had survived so long was nothing to do with passengers and everything to do with seed potatoes.”

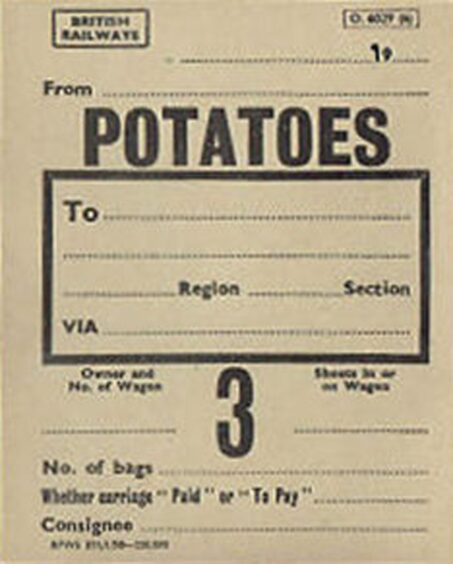

Ah, the tattie wagons.

Mark’s nemesis lay ahead.

The covered wagons where like battered and bashed sheds on wheels, capable of carrying 12 tons of seed potatoes.

The seed potato merchant to be reckoned with in the area was John O Gordon of Balmuchy, who supplied growers in Norfolk and Lincolnshire.

Mark said: “It was effectively their business which had kept the station open when so many others closed in the early Sixties.

“You got the feeling if John O was displeased a certain amount of discomfort would be felt in the Area Manager’s office in Invergordon if not further afield.”

Seed potatoes are valuable. And they are delicate and fussy.

“If it’s too hot, they start sprouting before they should, ” Mark went on.

“If it’s too humid, they sweat.

“Even worse, if they get frosted, they go black and mushy, it spreads and the whole load is a write- off.”

The tattie wagons had to be wall-papered

There was a solution, and it didn’t go down well with the teenage mutant railman.

The old vans needed to be wallpapered before any potatoes got loaded into them.

“Yes, someone, somewhere, doubtless after an insurance claim for the replacement and disposal of 12 tons of black mush had decreed that all vans carrying seed potatoes were to be lined with thick brown paper as insulation to protect against frost,” Mark says.

He can still give detailed instructions about how to pre-cut the rolls of brown paper, head for the goods yard through wind and rain bearing the paper and a staple gun, if you hadn’t forgotten it, and in the dark, with wet paper and frozen hands get stapling.

‘It was like nailing jelly to a wall’

First along the wagon, then across, praying the gun doesn’t run out of staples or jam. Which it invariably did.

“It’s particularly hard to hold the paper up sideways and staple it at the same time. Like nailing jelly to a wall,” Mark says.

But he takes pride in that, to his knowledge, none of his consignments were lost to frost, or mislabelled.

Eventually the job was done.

“One Friday afternoon, all the men gathered in the booking office to thanked and paid by the great man himself. John O Gordon was visiting the station.

“Ceremoniously each of the men was given a bottle of whisky.

“Finally John O turned to me and said: ‘This is for you.’

“There was an expectant, slightly nervous silence.

“John O had just handed me a tin of toffees.”

Mark rose with grace to the occasion.

“In a gentle, Highland way he was saying I was a useless article who couldn’t even be relied on to paper a potato wagon efficiently.

“And he was absolutely right.

“There was only one thing I could do.

“I smiled and said, ‘Oh I love toffee’, thanked John O Gordon and offered them round.”

After a year, the game was up for Mark’s station idyll.

His caravan on the platform, mattress in the kitchenette, record player in the ticket office and general unconventional approach to the job had been sussed out by the higher ups.

So he jumped before he was pushed and handed in his notice.

Mark stayed in the Highlands

Mark went on to many different callings in the Highlands, including playing guitar in bands semi-professionally for twenty years, running his own IT company and writing a monthly column for the Collectors Gazette about model trains for 27 years.

He says he loved trains before he took on Fearn, and his passion for railways has never left him.

Now living in Inverness, he still travels on the Far North Line from time to time.

“Trying to make it pay is impossible, it’s a social thing, a heavily subsidised 200 miles of railway which is actually slower than the road.

“It’s really a tourist and social railway although Hi-Trans are doing all they can to try and maximize its value.”

You might enjoy:

The ‘Railway Duke’: Celebrating 150 years of the Golspie to Helmsdale line

Conversation