Visitors to the Nairn Show 2024 were treated to the most eerie and unique of sounds to round off the day’s entertainment.

A very loud, low, vibrating drone filled the new showground at Davidson Park and beyond to the town.

It blasted forth amid clouds of steam from a huge tractor, an iron monster dwarfing every other tractor in the show, a 28-tonne steam traction engine named Erebus.

And the sound?

The smart phone footage above doesn’t do it justice, but it’s the closest it’s possible to get in 2024 to the noise of the whistles sounded on RMS Titanic at noon every day of her doomed maiden voyage.

When the steam clouds cleared from around Erebus’s funnel, three gleaming bronze bells appeared, reproductions of the original whistles, forged in Aberdeenshire.

Meet the man behind the Titanic whistle steam engine project

The man behind this possibly quite mad project is Cameron Anderson, co-owner and operations manager at Subsea Tooling Services in Oldmeldrum.

Cameron and his wife Emily, his graduate-apprentice Findlay Lawson and engineer Hugh Watson make up Team Erebus, the brains and manpower behind Cameron’s dream of recreating the sound of the Titanic whistles.

It was precisely a year ago that Cameron came up with the idea.

He said: “I watched a video of the actual Titanic’s whistles being sounded by compressed air, and thought the whistles would sound completely different with steam.

“They were made with a set of whistles recovered from the wreckage in the 1990s and too vulnerable to sound them with steam.

“I thought, we’ll never get the chance to sound them with steam because they’re so fragile, so let’s make a replica of them and sound them using steam from Erebus.”

He added: “Sometimes I get a bit of a notion to do something strange or odd, but this is my biggest project.”

Cameron has undertaken many other restoration projects, although nothing on the scale of Erebus.

He’s now close to finishing a 1930 Buick Marquette, having already restored a 1952 Field Marshall Series 3A, a 1949 Field Marshall Series 2 and a 1936 Austin Sherborne.

Not to mention a 1928 Buick Master Six which starred in Peaky Blinders 2021.

A Titanic project to capture a sound lost to time

But nothing has fired his imagination more than the Titanic project.

He said: “The Titanic whistles are triple Smith Hysons, probably last made about 110 years ago.

“On Sunday April 14th 1912 they would have sounded them on Titanic at noon for the last time.

“The ship hit the iceberg at about 11.40 that night and by 2.30 in the morning she was gone.”

Cameron and his team used the same type of bronze used in church bells for the project.

Instead of being cast in moulds, as they would have been originally, the team machined them into £50,000 worth of perfection, weighing half a tonne.

They designed and engineered the pipe work known as the manifold, which goes up to the header valve.

“That’s the isolation valve that isolates the steam to the manifold,” Cameron explained.

“Once we’re ready to sound the whistles, we’ll open up that header valve and that allows pressure to the two wing valves either side and they will sound the whistles.”

When the whistles sounded for the first time, they hit the top of Cameron’s decibel meter, registering 106 db with nowhere to go after that.

The three bells sound together but in different frequencies, like a chord, and the result is a deep, reverberating growl.

Findlay, 20, Cameron’s apprentice, said he has had his eyes opened by integrating modern day technology such as CAD (computer-aided design) and 3D modelling to recreate the bells.

He said: “We sat down for a few design meetings, there’s no drawings for the whistles and nothing ready-made.

“Eventually we pulled dimensions off what we know about Titanic, and then reverse engineered the whistles to be the same scale was what we think they were.

“It sounds really good and the engineering behind it has been so interesting.”

Findlay, from Netherley, Stonehaven, has also been blown away by working on Erebus, the giant steam traction engine which powers the bells.

Erebus is one of originally eight 1922 Fowler Z7 engines, made by the John Fowler works in Leeds.

Far too big to work the farms in the UK, they were designed to work overseas, and went to Sena Sugar Estates in Mozambique.

Eye-opening British engineering

Findlay said: “It’s really opened my eyes up to how they did it back then, and what could be done in Britain with British engineering.

“You can look at these steam engines all built in house in Leeds, none exported to China to build abroad, all built here, showing what British engineering used to be, how good these people were and how smart, being able to do what they did with such simple mechanics, used in a complicated fashion.”

The engines worked hard in Mozambique until the 1950s.

“Erebus would have had a sister engine it would have ploughed with, chained together some 600 yards apart,” Cameron said.

“The big winch is what pulls the plough and the plough’s attached to a wire.

“You have two engines and they pull the plough between them.

“Out there they were ploughing much deeper, they needed a lot more horsepower, so two engines were needed to pull the plough.”

At 25 horsepower, the Z7 engine was far more powerful than the average British steam engine in the 1920s at about 6 hp

A day’s ploughing would have cost a couple of tonnes of coal per engine.

“By the 1960s the Z7s were old technology and were pushed to the side of the field and left to rot,” Cameron said.

“They were spotted lying there and eventually word got out to UK steam collectors.

“Three men pulled some funds together, travelled out to Mozambique and made a deal with Sena Sugar that if they could get the engines back to the UK they would have them for free.”

All eight of the original machines were there, but the sister engine to Erebus was found with its rear axle broken so it was decided to leave it there.

Cameron said: “They got seven engines out but sadly lost on of them in the Zambesi river when it fell off the side of a barge and was lost forever.

“Out of the original eight, they got six back and this is one of them. The rest are in England, in private collections.”

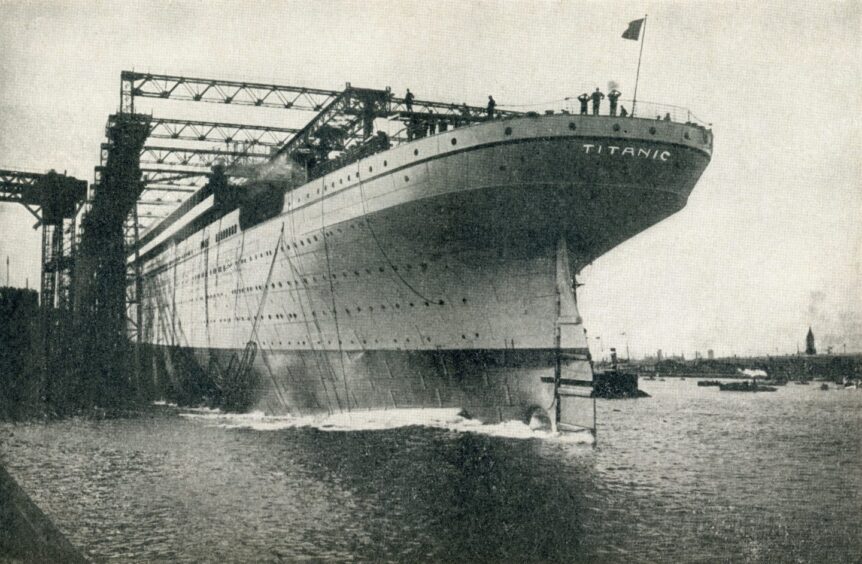

Next year, Team Erebus has been invited to sound the whistles in the Harland & Wolf shipyard in Belfast, where Titanic was built.

“We’ve also been asked to take it to Southampton where Titanic departed on April 10, 1912, and sound the whistles at the same time that she departed,” said Cameron.

Cameron and Team Erebus are constantly mindful of the loss of life in the Titanic disaster.

Cameron said: “We’ve got two big brass plaques getting made right now dedicating the whistles to the ship’s engineers.

“When the ship was sinking they all stayed at their posts and made sure there the power was still going to provide lighting so people could get out.

“Sadly the engineers all perished. They all stayed at their posts and made sure that as many people as possible that could get off without being stuck in the dark, so there will be a big brass plaque on either side dedicating the whistles to those engineers.

“It’s important to remember there’s a human side to this as well.”

You might also enjoy:

Could Titanic links be fuelling horror haunting of former West Coast hotel room?

Revisiting the fading glory of one man’s dream, the Inverness Titanic

Conversation