For Jacqueline Willis, there is nothing better than a calm, blue day at Donmouth Beach with the sun shining down on a WWII pillbox silhouette.

Particularly when coming across her favourite one catchily named NJ91NE0089 or as she calls it, pillbox number two.

She said: “On a cold, calm day down the beach where the sun is shining because of the green colours from the algae that come off that one, it’s just sitting there in all its glory.”

When she moved to the Donmouth area 12 years ago, the wartime concrete hut was whole, and people enjoyed exploring inside the structure.

These days, the pillbox sits in pieces near the sea’s edge but still, argues Jacqueline, “stuck together”.

Out of the six left on the stretch of beach from North Donmouth Beach to Blackdog, it is the one that has changed the most.

The Gray’s School of Art graduate said: “I’ve been down to the beach in all sorts of conditions, and I am watching this thing beat the waves, and be swallowed by the sand, only to come out the next high tide.

“And suddenly it’s there in its glory. And as if to say, ‘Ha, I’m back.’

“I found myself drawn to that one most because I think that one encapsulates how resilient these things are.”

The 45-year-old artist has been so intrigued by these structures she has put together a project to explore their history and how the pillboxes – built in a time of uncertainty and conflict – are used today.

Read on to find out what stories she’s unearthed from the shifting sands of time…

These WWII structures point to a lost generation

Using photos taken over the last year and interviews with dog walkers, artists and geographers, Jacqueline said: “I’ve been trying to record these experiences of the beach so there’s a bank of information because it’s very changeable.

“During this project, I’ve had a pillbox go from completely covered to then exposed.

“Suddenly we have that example there of a previous generation.

“It’s trying to make people aware of the changeable status and how we are losing a resource.

“So that when a pillbox covers itself or uncovers itself in many generations there’s going to be a ‘I wonder what that is’.

“And then we can go back and find out not just about the war, which is very important but also what happened in between the war and the generations after because they’re the people that built the society we live in now.”

What are pillboxes?

The name for the concrete forts originated from their design.

Many of the pillboxes are built in various designs in round, square or hexagonal shapes with slit windows.

Their shape led them to be compared to the medicine containers made to store pills because of the various shapes while the slit window was said to resemble the letter slot on a post box or ‘pillar box’.

These comparisons resulted in the term pillbox which was said to first appear in print on the front page of The Times newspaper on August 2 1917 before it became more widely used.

Around 28,000 of these structures, made to house machine guns mounted on the concrete tables inside, were commissioned during WWII in order to protect Britain’s vulnerable coastline.

To stop “the soil of Great Britain from being fouled by an enemy footprint” defence plans including the creation of anti-tank defences and pillboxes were made.

Jacqueline said: “There are hundreds of thousands of these structures all over Britain. Anywhere there’s an exposed coastline, there will have been a pillbox there.

“People were afraid for their lives, to the point that they put hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of concrete down there to ensure we wouldn’t be invaded.”

Newburgh man created northern Scotland defences

In an article from the Press and Journal’s parliamentary correspondent on July 4 1940, Lord Croft predicted a “funeral pyre” of enemy tanks should they ever reach British shores.

He declared: “If he (Hitler) gets so far we hope to defeat him in landing and, if not, then we intend to fight him on the beaches and hurl him back into the sea.

“We must be ready for any eventuality…it is essential that every landing place should be covered by gunfire and rifle fire.

“Hence it is of the greatest importance that the Local Defence Volunteer movement should recruit to the full in the coast towns and villages and that they should be so organised as to be able to proceed at speed to their positions.

“I would like to see a bonfire of enemy tanks if they ever landed in this country. Our men can and will dominate and master the machine.”

An order to erect defensive lines of anti-tank concrete blocks linking pillboxes quickly followed.

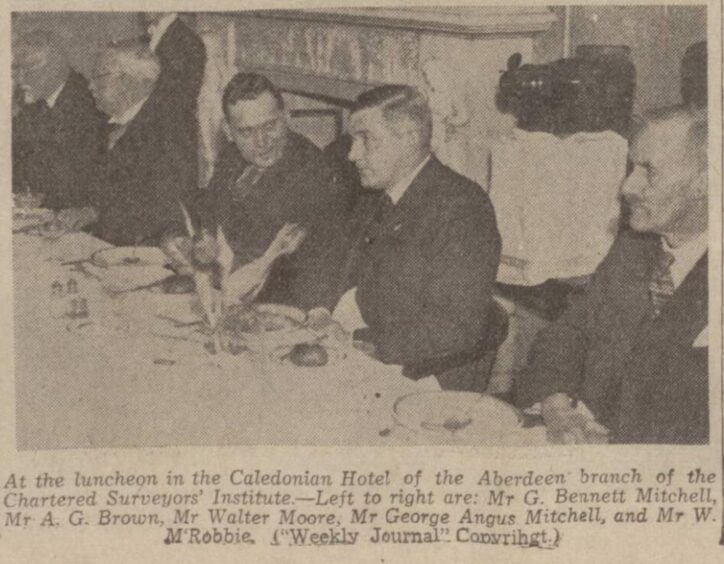

In the north of Scotland, the man put in charge of installing this from Forth to Wick was Chief Royal Engineer George Angus Mitchell from Newburgh.

Son of George Bennett Mitchell, one of Aberdeen’s best-known architects, Mr Mitchell followed in his father’s footsteps as an architect and surveyor and was a veteran of the First World War.

He was involved with numerous projects including the building and reconstruction of Haddo House, Cluny Castle, north-east hospitals and alterations to Marischal College and University of Aberdeen buildings.

‘Hitler’s Graveyard’ fittingly found on Newburgh Beach

In just a few months in 1940, Mr Mitchell had organised the construction of an array of beach defences which included concrete blocks, barbed wire entanglements, pillboxes, minefields and gun emplacements.

Jacqueline said it would have been a massive undertaking hauling concrete and materials down to the beachfront.

According to Janet Jones, in her book A Portrait of the Parish of Foveran, the contractor for the defences commandeered all the useable tractors and carts in the locality to take cement to the site.

Surely a popular endeavour with local farmers at the time.

The tank blocks were usually cubes of concrete cast on site with jagged stones set on top and then laid in a long line at the high water mark along beaches.

Sometimes the people building the blocks scratched their names or messages on the still-wet concrete.

A locally famous example of this is the decorated tank trap fittingly found on Newburgh Beach signed by Louis Lawson, presumably one of the men making the defences.

Named “Hitler’s Graveyard”, it depicts a caricature of Winston Churchill and also Adolf Hitler, who is looking up at a falling bomb.

At the bottom of the block dated 1940 are the words, “Hitler’s Graveyard”.

‘Even if a grenade was thrown in the structure should still survive’

The construction of the pillboxes near Donmouth started a little later in the war in 1943.

They were built to withstand heavy warfare and like the many built on the front, would have been difficult to attack.

“These were built to withstand heavy mortar attacks,” said Jacqueline.

“The idea would be that if somebody managed to throw a grenade in there the grenade would go off but the structure would still be standing and still be of use.”

Once completed they were manned by members of the Home Guard but thankfully never used in combat.

After the war, many anti-tank barriers in more visible spots like at Aberdeen Promenade were demolished in 1946.

At the time, it was asked if this could be done in a “tidy and safe manner before the summer holiday season began”.

What happened to the pillboxes after the war?

But ideas on what to do with the pillboxes differed.

Some, like some pupils at Axe Vally School in Devon, launched an appeal to convert a former WWII pillbox on their sports field into a hibernating area for bats as reported by The P&J in 1994.

Others labelled the relics “eye-sores” and seemed keen to get rid of the “grim reminders” of the past.

In 1971, the P&J reported a Sandend pillbox “disappearing in a cloud of smoke” after the army blew it up under a “blazing sun”.

The paper reported: “They provided a pleasant treat to holidaymakers who had temporarily to vacate the beach and at the same time removed a blot from an otherwise pleasant landscape.”

Six years later, Newburgh residents within a mile of a coastal pillbox due to be blown up were warned to keep their windows open because the shock wave could damage glass.

Inspector Ken Tough from Inverurie added the risk of this was only “slight”.

People were also told to keep 1,000m away to avoid being hit by “flying debris”.

Another two pillboxes at Foveran Links and Drum Links deemed unsafe were blown up a couple of days later while a fourth at the mouth of Blackdog was labelled as too close to a house to blast.

For those left to the elements on beach fronts, many became lost in time and sand.

How does Scottish weather do one better than a grenade?

Despite their seemingly indestructible structure, a lot of the exposed pillboxes are no longer intact.

Describing how this happens Jacqueline said: “The pillboxes were actually built in dunes. You can still see some of this if you go up to Balmedie.

“There are ones that have tumbled over that were sitting on dunes and have been flipped over because the sand underneath them has worn away.

“The force of nature it takes to do that is immense.

“You get these big storms coming in and one minute you can have a whole entire pillbox and then the next minute the bottom of it has snapped off and the walls have lifted off.”

With these broken pieces of war still left standing in a time of peace, Jacqueline has been creating a bank of stories and images to explore their changes and the new memories being created in them.

And to remember them before they disappear completely.

Swapping danger for the ‘magically’ mundane: What they mean to people now

Watching beach users interact with them, she said: “Suddenly they’re not pillboxes that people would be shot from. They’re children’s castles, they’re places for folk to shelter when it rains.

“You get folk going down there drinking wine and having a little party.”

With her two grandpas serving in the Navy, she added: “I was speaking to these three kids who called it a temple like Indiana Jones running about it all day.

“For me, that’s an example of how something very mundane, disregarded, not given a second thought, has enriched that child’s life.

“That’s the kind of world our grandparents have built for us, that we can go off and we can have these incredible adventures in a very mundane world, but very, very safely.

“As slight and mundane as those interactions are it means when they do eventually go into the sand they will actually be missed.”

As such, Jacqueline said they deserve to be noticed and honoured for the “little bit of magic” they give people today.

She has put these changes and stories together in an exhibit in partnership with Creative Scotland at the Anatomy Rooms at the Ardake Gallery, Aberdeen running until August 20

Conversation