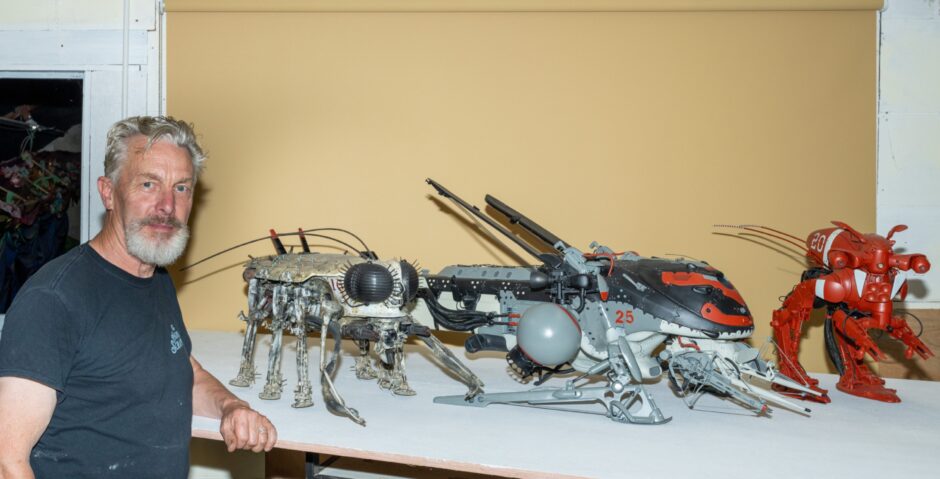

The reasons why Mark Stevens has made 34 ‘sinister and nasty’ models over the past three decades are complicated.

The models are like the worst kind of military hardware crossed with the most horrible kind of insect.

They’re made entirely from junk, mainly plastic, and despite their dark side, they’re unique works of art.

Parts of hoovers, washing machines, computers, cameras, binoculars, hair brushes, car windscreen wipers—Mark turned all the detritus of modern life into creative gold.

His highly detailed models are mesmerising to look at, but you can’t help wondering what was going on in the mind of their creator.

It’s taken Evanton-based Mark, 71, most of his life to find the answers to that question.

He developed his skills early, being an obsessive modeller from the age of around five.

He said: “There were no phones then and only basic TV, so boys built aeroplanes, ships and tanks.

“It’s what you did at the weekend, you took your two shillings to the post office and bought an Airfix kit.

“Because we had won two world wars and were facing nuclear Armageddon, they were usually militaristic models.”

That’s one clear influence in his later 30 year series of dark, macabre models.

In his early teens, Mark’s parents bought him ever more complex models.

“It was to redress the balance because my brother and sister were having a lot of money spent on them in the pony club,” he says.

“So I got state of the art stuff from Japan, costing around £25, a lot of money in the 70s. They were mostly big F1 racing cars, 1:12 in scale.

“Some were motorised, you could put a battery in them, so my skills were honed at an early age.”

But from the tender age of 7, another traumatic influence in Mark’s creative process was present.

He was sent to boarding school, which he hated.

He said: “It alienated me from my parents and family, I stopped trusting, respecting and loving because of it.

“It was peer pressure and what was expected of my parents at the time, but it affected me badly for a long time.

“Building models was like an armour against the trauma.”

Once you understand this, Mark’s early influences and pain are obvious in his models.

But there’s even more to it than that.

While in Australia for a couple of years in the 1970s, Mark noticed a disturbing trend taking off, single use plastic.

“I was becoming aware of how much plastic was thrown away and how much was becoming disposable and I thought, this is not going to end well.

“It was marketing. Single use cups, cutlery and razors meant you would buy more.

“You were throwing away something which two years earlier you would have washed and put away.”

Mark’s response was to start making things out of the plastic rubbish.

He said: “I saw Star Wars and made a starship which was just plastic cups and cutlery all glued together and sprayed. It wasn’t made to last, and probably fell to bits and got thrown away, but it had a brief second life.”

He went on to make a series of starship models, which were quickly picked up by an art gallery for a solo exhibition.

They were an immediate success, and Mark sold enough of them to pay for his passage home from down under.

The model-maker extraordinaire comes originally from Wrexham, North Wales, and came to Lentran, near Inverness when he was 13 for his father’s business.

In his 30s and 40s he spent many years in London, studying at Camberwell Royal School of Art, then staying on for 13 years as a studio technician in the metalwork department.

He moved back to the Highlands after that, picking up work here and there.

Passionate about motorcycles and bicycles, he worked in a motorcycle dealership until that had to close.

Gerald Laing’s assistant

He was sculptor Gerald Laing’s assistant for a few years and worked with Northern Lights on stained glass restorations on churches in Inverness and around the Highlands.

The Strathdon sculptor Helen Denerley found in Mark the perfect collaborator for many of her scrap metal projects.

His first project with her was on her public artwork, two giraffes, Martha and Gilbert , situated at the top of Edinburgh’s Leith Walk, outside the Omni Centre.

Mark said: “She came to Evanton because this was the only place she could find that had a 24ft wall in a warehouse for doing the drawings.

“I heard on the grapevine that there was somebody looking for someone to assist her to build a giraffe out of scrap and apparently, she’d had several people come in and do a day’s work with her.

Helen said yes

“I went along, and it was a bit like a day long interview, we just worked together and at the end she said yes, let’s do it, I can work with you.

“Because I’d spent 13 years working with students helping them with their projects, I would ask her what she wanted to achieve and how she would like it done, instead of giving her my opinion or taking over.”

Now in more mellow years, Mark has stopped making his nasty, sinister model series.

He said: “Once I understood why I was doing them, it was as if I was healed from that childhood trauma, and I stopped.”

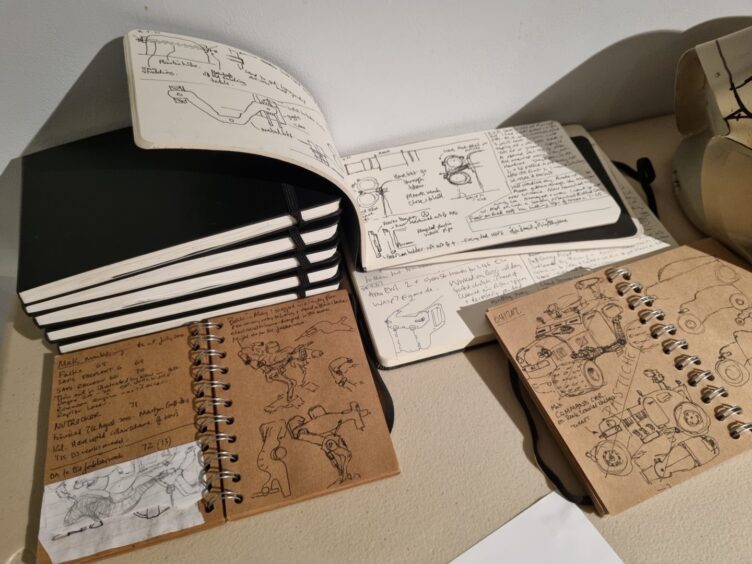

He’s now reverting to happier childhood times and building models from kits, albeit very grown up, sophisticated ones.

It’s not easy.

A love-hate relationship

“They take an awful lot of effort, and I find myself having a complete love-hate relationship with the whole process. I remember struggling for three weeks with the back end of one piece.”

He looks back on his war models and now accepts they are art.

“I’m uncomfortable saying I’m an artist, although part of me thinks there’s a fine artist inside me, but when I get anywhere near anything like that, I feel pretentious.”

Mark occasionally shows his models in public and is working with Cromarty film maker David Newman on a documentary about his work.

Conversation