There’s a familiarity about photos of Aberdeen at war. We can place the streets and buildings, but the people peering back in black and white remind us that generations have slipped by.

In monochrome ink these faces can fade into the past.

But more than 80 years on, we’ve used advanced artificial intelligence (AI) software to colour these precious photos from our archives of Aberdeen’s darkest hours for the first time.

While the hues may not be exactly as they were, the high definition reveals new details about Aberdeen’s war.

Colourising these archive photos has put colour back in the cheeks of those young Gordon Highlanders bravely marching towards an uncertain fate.

But it’s also brought some life back to the home front, when Aberdonians carried on in the face of tragedy and adversity.

Step back in time through each year of World War II as it affected Aberdeen in colour below…

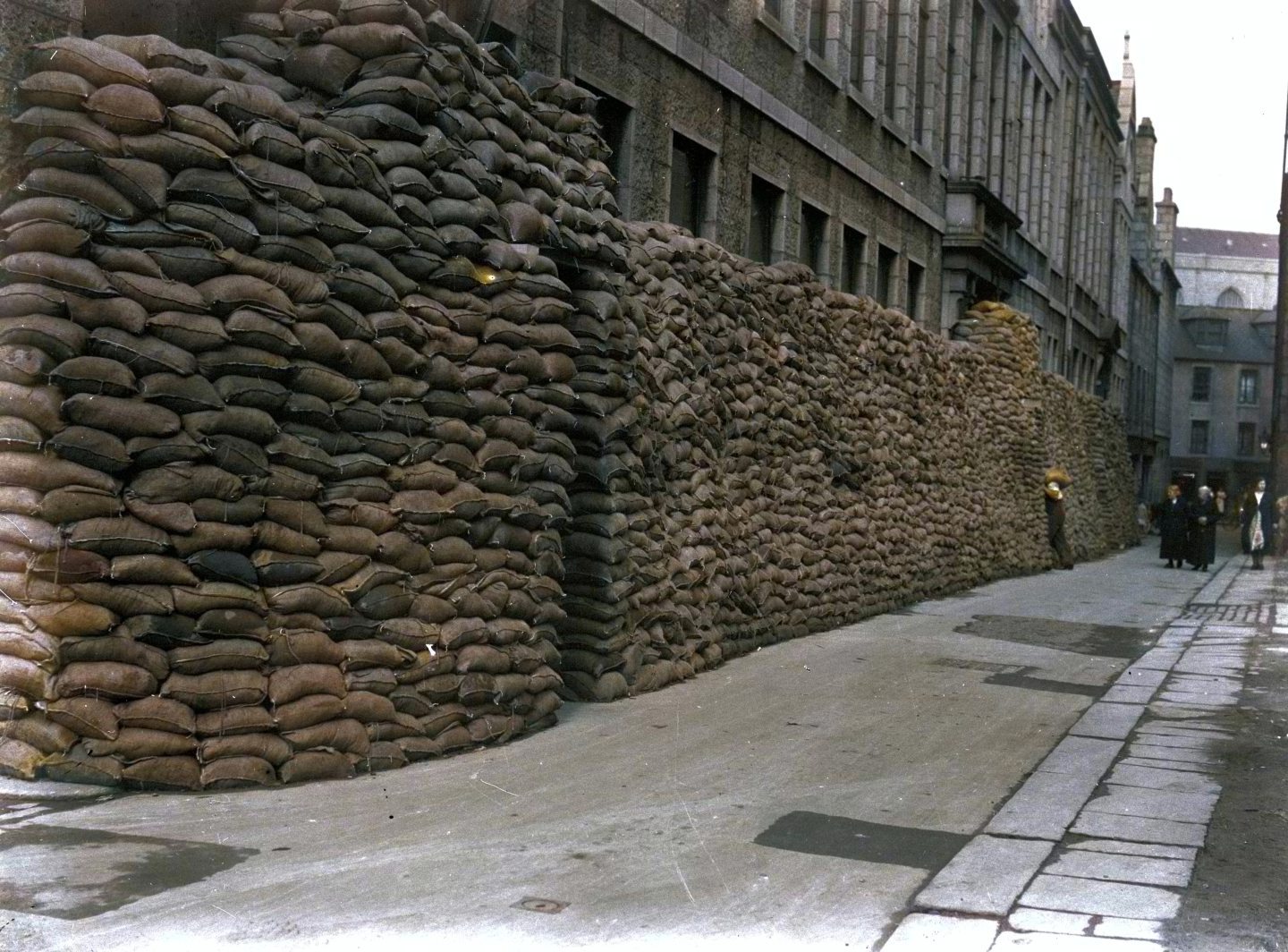

1939: Sandbags and soldiers as Aberdeen prepares for war

On September 1 1939, the Evening Express front page warned the King had signed an order allowing the mobilisation of the Army, Navy and Air Force.

If Germany did not retreat from the Polish frontiers, Great Britain would declare war.

Hitler did not respond.

In a five-minute radio broadcast at 11.15am on Sunday September 3, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain confirmed: “This country is at war with Germany.”

Many people heard the news from the pulpit in church.

And back in Aberdeen, special editions of the Evening Express were printed, with crowds congregating around newsboys.

Children evacuated from the Central Belt were already settling in Aberdeenshire, and Aberdeen began to prepare for war on the home front.

1940: The bombs start falling on ‘Siren City’

Although preparations began, life seemed to carry on as normal in Aberdeen after war broke out.

There was a stalemate in Europe during the Phoney War, which lasted until May 1940.

But that all changed in July 1940 when a scatter of bombs fell over Aberdeen.

Due to government press censorship, the newspapers couldn’t report the tragedies at the time in case it affected morale.

It was the following year before the scale of the tragedies flitting through Aberdeen was made public, with women and children making up the majority of casualties in air raids.

In August 1940, Mrs Sherriffs was killed when a bomb landed on her house on Forbesfield Road, and blew the whole roof into the garden. Her husband narrowly escaped with his life.

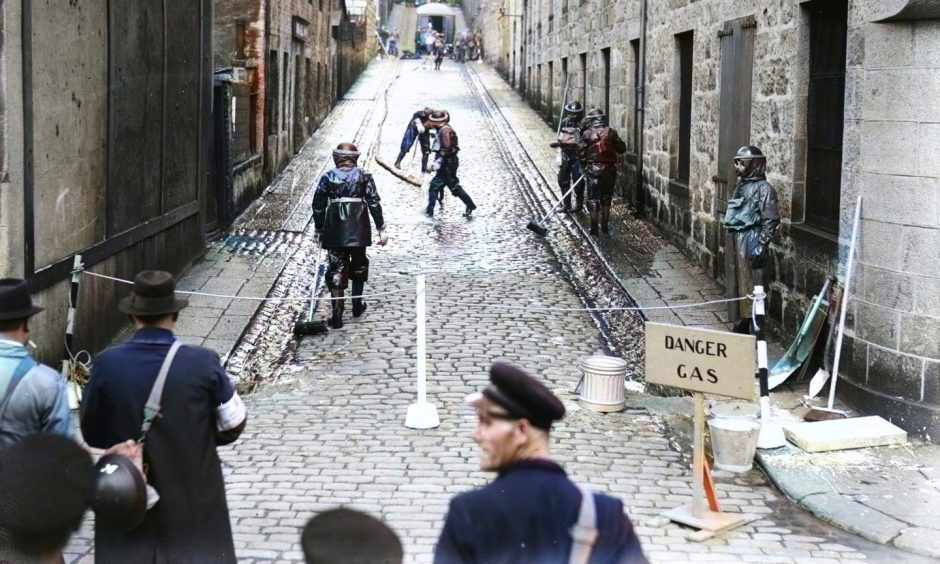

1941: Dramatic gas attack tests carried out in Union Street

As war rolled on, there was a grave fear the Nazis would begin dropping gas bombs on Aberdeen.

In the summer of ’41 large-scale, realistic mock gas attacks took place in the city centre.

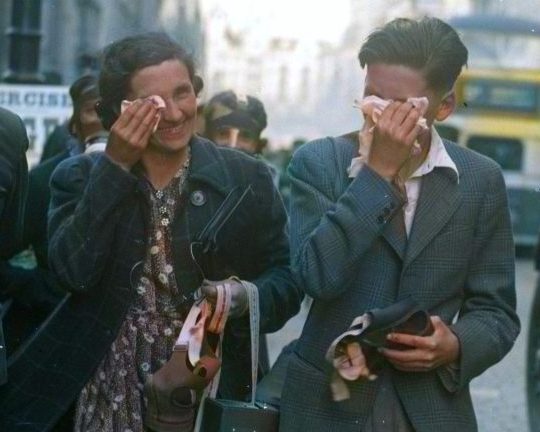

Thousands of Aberdonians wearing gas masks filled the streets from Belmont Street to Broad Street, as clouds of manufactured smoke poured from nearby buildings to simulate gas.

Over the course of an hour, various smoke bombs went off, creating apocalyptic scenes as trams eerily emerged from clouds of smoke.

People who did not take their gasmasks out with them learned a hard lesson as tears streamed from their stinging eyes.

But the gas test caught everyone’s imagination and was taken in “rare spirit” all round.

1942: Cathedral railings ripped up for scrap iron

With no end in sight, the war effort on the home front increased with the removal of railings from properties and cemeteries up and down the country.

Aberdeen was no exception, and in 1942 workers began dismantling railings in the city’s cemeteries, with 50 tons collected from St Machar’s Cathedral alone.

It was widely believed the iron could be melted down and used for the manufacture of weapons.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s believed much of the sacrifice of railings was in vain, as there was far more than ever needed.

But it was fantastic propaganda and a unifying act which made people feel they were doing “their bit” back home in Aberdeen.

In reality, a lot of scrap metal was squirreled away in railway sidings out of view.

1943: Bombs continue to fall as Aberdeen faces darkest day

But come 1943, even press censorship could not hide the true devastation of Aberdeen’s darkest day.

In the space of just 44 minutes on April 21, 127 bombs fell, damaging or destroying more than 12,000 homes and killing 98 civilians and 27 soldiers.

Parts of Aberdeen around Powis, Causewayend, Cattofield and Kittybrewster were particularly badly affected.

Some entire families were wiped out in a night of terror and tragedy.

Peter Nicol, who was staying at a friend’s house in Cattofield during the bombing, said: “Cattofield not only had a rain of bombs, but the street was raked by a hail of bullets.

“What a scene of devastation hit my eyes – the house next door had simply disappeared.”

1944: Aberdeen’s ‘stay at home holidays’

The summer of 1944 brought the D-Day landings, which marked the beginning of the end of the Second World War.

In what was the biggest air and sea operation of all time, the Allies landed around 156,000 troops on the beaches of Normandy.

Back in Aberdeen, in the days before the internet or even phones in every home, people congregated around news vendors to find out the latest from the front line.

But there was a bit of light relief in the dirge of war, when Aberdeen held its ‘stay at home holidays’ week in July ’44.

A plethora of activities and attractions were held throughout the city, including swimming galas at the city’s pools, picnics and dancing at Hazlehead Park.

But the lack of men to participate in dances was a reminder that war was never far away.

1945: Relief as tragedies turn to triumph with end of war

It had been a long war of sorrow and sacrifice, rationing and restrictions, but hope was on the horizon by spring 1945.

The Evening Express headlines carried more positive headlines about the allies.

On May 2 the front page declared “cracked Reich on its last legs”, two days later it read “Nazi army now only a rabble”. And on May 7, simply: “Unconditional surrender.”

The war in Europe was over, there was jubilation and the city was decked out in flags, Aberdonians thronged on to streets with utter disregard to trams and traffic.

But it wasn’t until victory was declared in Japan that it was truly over.

While the newspapers still carried photos of casualties, there was relief and joy as wives and mothers were reunited with their husbands and children in Aberdeen.

ALL IMAGES IN THIS ARTICLE ARE COPYRIGHT OF DC THOMSON AND HAVE BEEN COLOURED USING ADVANCED AI. UNAUTHORISED REPRODUCTION IS NOT PERMITTED.

To purchase archive photos, contact archives@dcthomson.co.uk

More Past Times stories

I spent a week living on my Aberdeen grandma’s wartime rations and recipes: Here’s what I learned

Remembering Archaeolink, the living history park in Aberdeenshire

Conversation