The locomotive works may be long gone, but the railway was the lifeblood of Inverurie. Had the station not opened 170 years ago, Inverurie wouldn’t be the town it is today.

The railway brought thousands of people and mass employment to Inverurie in the early 20th Century.

It turned a rural market town, where agriculture was the predominant employer, into an industrial stronghold for decades.

But if it wasn’t for the fighting spirit of townsfolk in the 1960s there would be no Inverurie Station today.

The station opened in September 1854 as part of the new Great North of Scotland Railway from Aberdeen to Huntly.

But 90 years later, Dr Beeching wanted it axed.

Great North of Scotland Railway proposed during ‘railway mania’

The GNSR from Huntly to Aberdeen was proposed during the great age of railway mania in the 1840s.

The first sod for the route was cut near Oyne in 1852 and the line opened on September 20, 1854.

From Aberdeen, the railway stopped at Woodside, Bucksburn and Dyce.

It then snaked between Pitmedden, Kinaldie, Kintore, Inverurie, Inveramsay, Pitcaple, Oyne, Insch, Wardhouse, Kennethmont and Gartly along the way.

The opening of the line marked a significant moment in Britain’s railways – an unbroken rail connection from the north of Scotland to rest of the UK.

A two-hour journey took passengers from bustling Aberdeen past grand houses, fields and farms, around Bennachie and through the glens to Huntly.

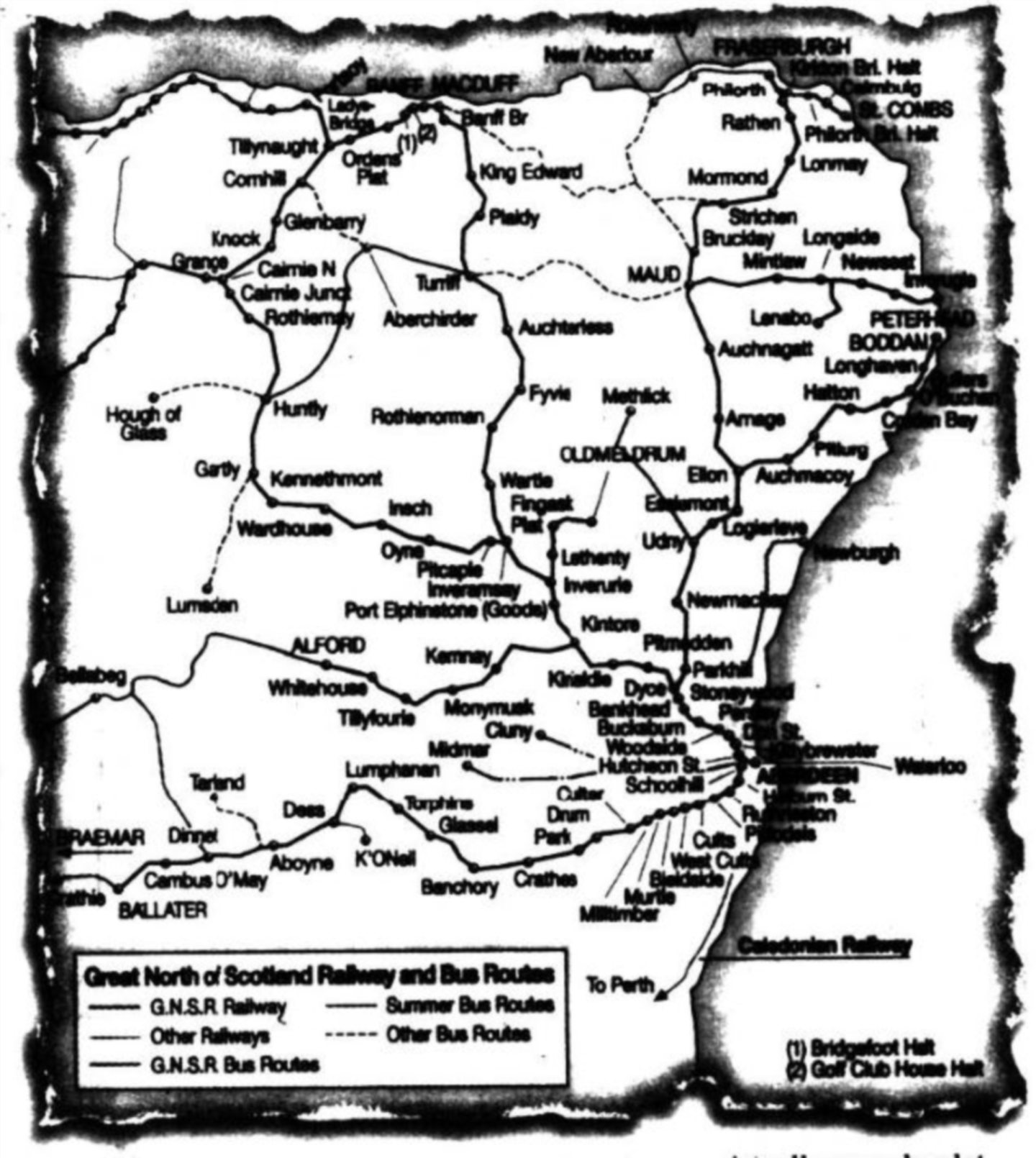

The original route to Huntly served as the spine for the whole system.

In the following years, as speculation in railways exploded, branch lines meandered off that spine, reaching practically every hamlet in the north-east.

1854: Inverurie quickly outgrew original wooden station

As well as running quick, efficient and cheap trains (the Aberdeen to Huntly fare started at 1p per mile for third class) GNSR had a system of buses to link rural communities to stations.

First-class passengers could apparently enjoy dinner carriage delicacies such as “Cream of Turriff Tomato Soup”, “Melon Meldrum Meg”, “Poulet Pitcaple en Casserole” and “Straloch Souffle”.

By 1856 the railway crept up to Keith and across to Oldmeldrum, the latter turning Inverurie into a junction station.

As the largest settlement between Aberdeen and Huntly, Inverurie was a kind of halfway point.

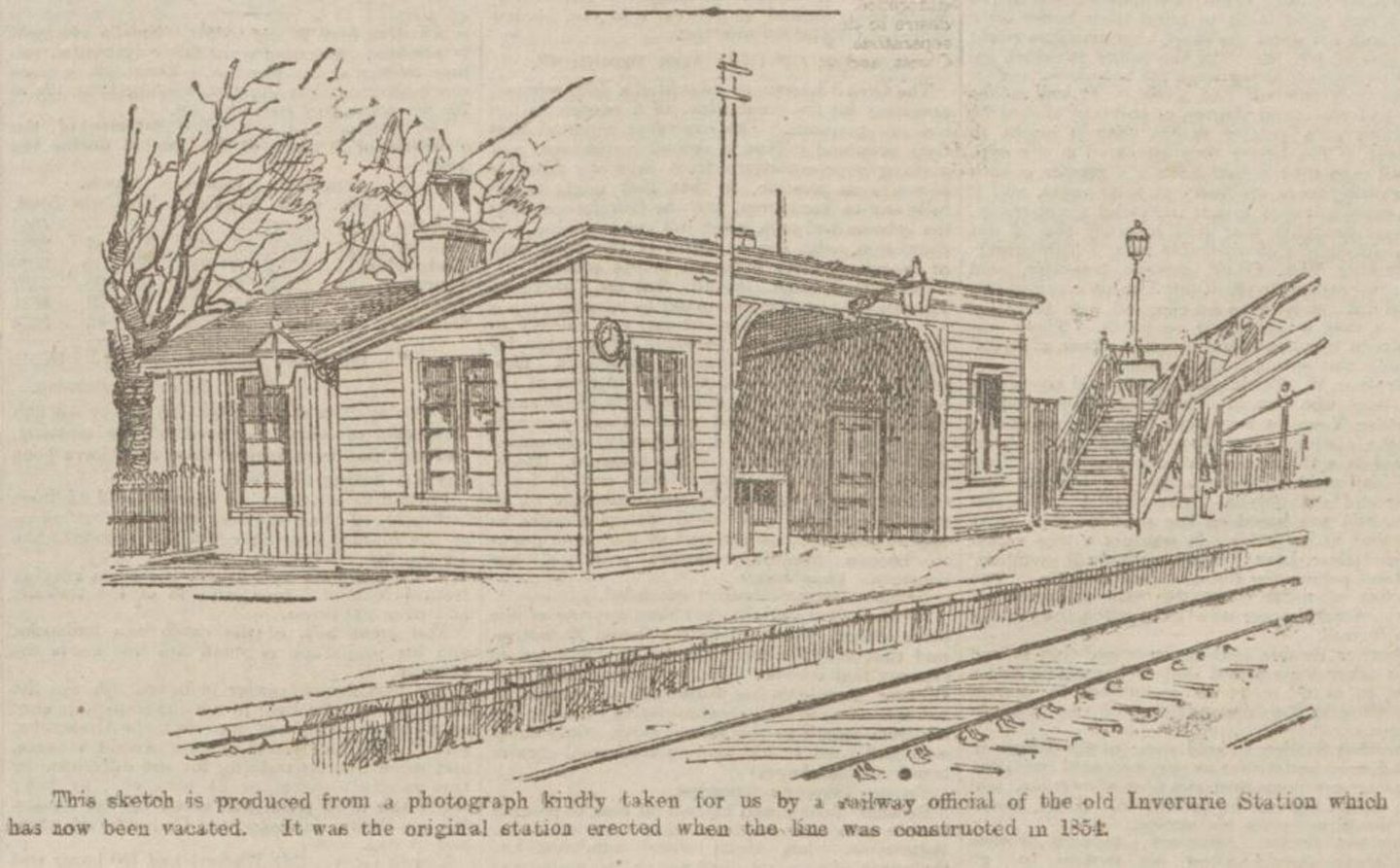

But today’s station was not the one that opened in 1854.

The original Inverurie Station was a wooden structure a little further south, located at today’s as Old Station Road.

Here it was close to the Earl of Kintore’s Keithhall Estate.

But by the turn of the last century, the locomotive works at Kittybrewster could no longer keep up with the maintenance and increase of rolling stock demanded by GNSR.

Instead, a vast site was identified just north of Inverurie to house a modern locomotive works, dwellings, a new station and goods yard.

1900s: Inverurie became industrious railway town

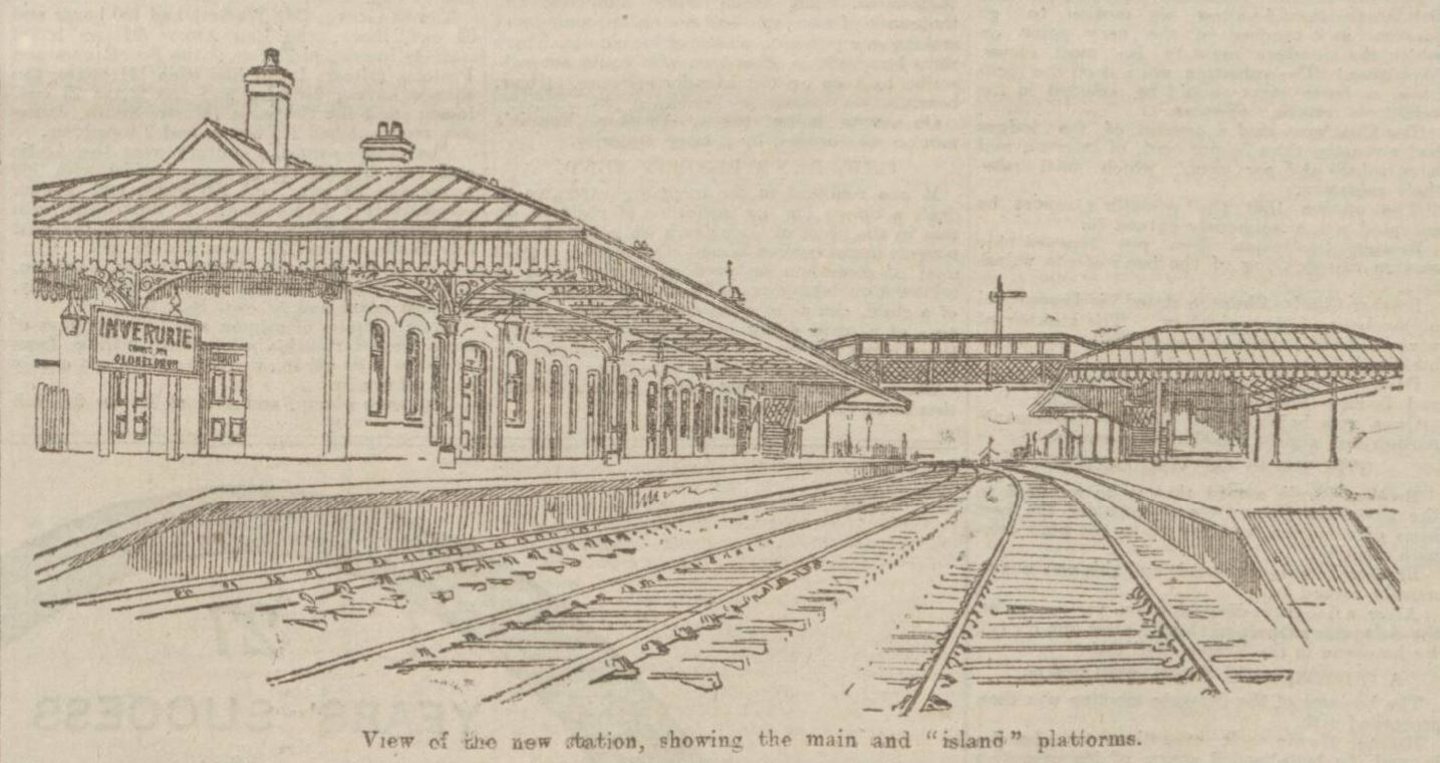

The new station would command a more central position in Inverurie, just metres from its town hall.

The new Inverurie Station was far grander than its primitive predecessor cementing Inverurie’s new position as a railway town.

It had a “commodious booking hall”, a general waiting hall, a ladies’ waiting room and a men’s waiting room.

As well as a station master’s office, porters’ room, left luggage and lamp room, it had a private waiting room for the Earl of Kintore.

Delightfully, the station still retains its Edwardian features today.

Although long gone is the original, huge glazed canopy held up by ornamental pillars which stretched 273ft (83m) along the platform.

The up and down platforms were connected by a covered footbridge, with smaller buildings on the Aberdeen side.

A signal box and goods station was built to the west of the passenger station, alongside an extensive freight yard.

Inverurie Station was one of the most modern in Britain when opened

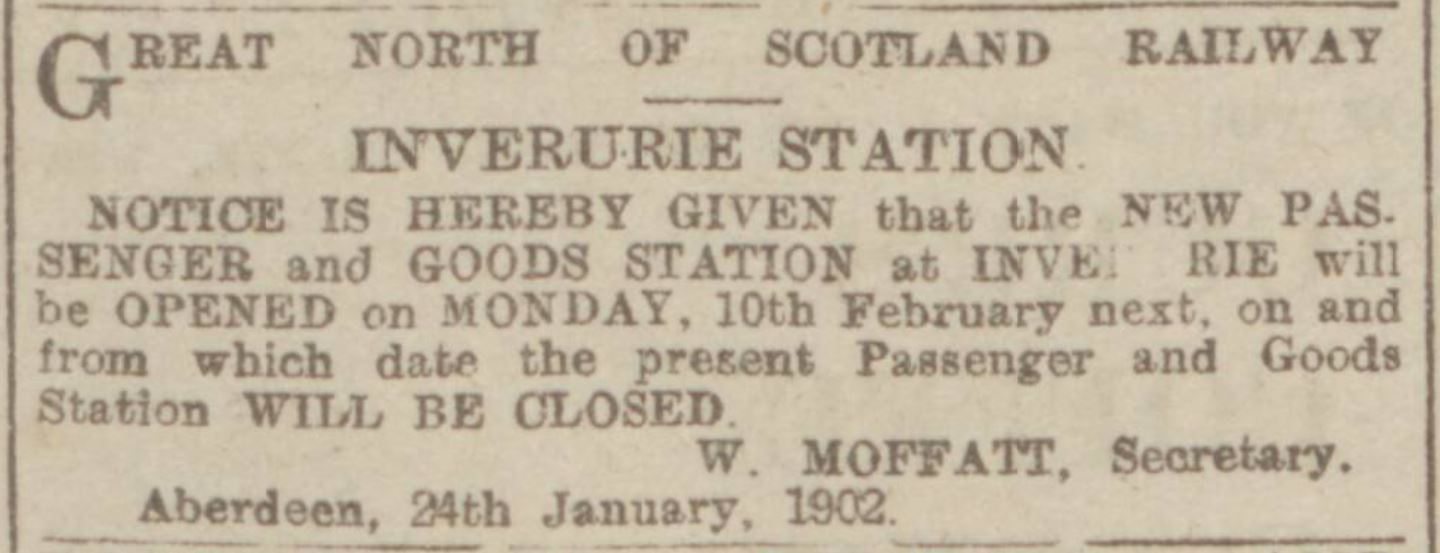

The new Inverurie Station opened on February 10 1902 marking the end of the line for the old station.

It was said the new station was “bound to play an important part in the future prosperity of the town”.

Casting some shade, Provost Jackson said the old station was “about as bad as that at Banchory, and that is saying a good deal”.

Adding: “However, all that is changed and Inverurie now rejoices in a station as handsome as that at Aboyne.”

At the time, it was described as one of the “most complete and up-to-date” stations in the whole of Britain.

The addition of revolutionary electric lighting saw it deemed the “ornament of the burgh”.

While there seemed to be a friendly rivalry between the Donside and Deeside lines, ultimately it would be Inverurie Station that survived the Beeching Report.

Shock when Dr Beeching sought to close Inverurie Station in 1963

But only just.

There was disbelief on March 27, 1963 when Inverurie – the railway town of the north – was included in chairman of the British Railways Board Dr Beeching’s brutal blueprint to reshape British Railways.

At this point, Inverurie’s population was nearly 5,000, with one in four people employed at the locomotive works.

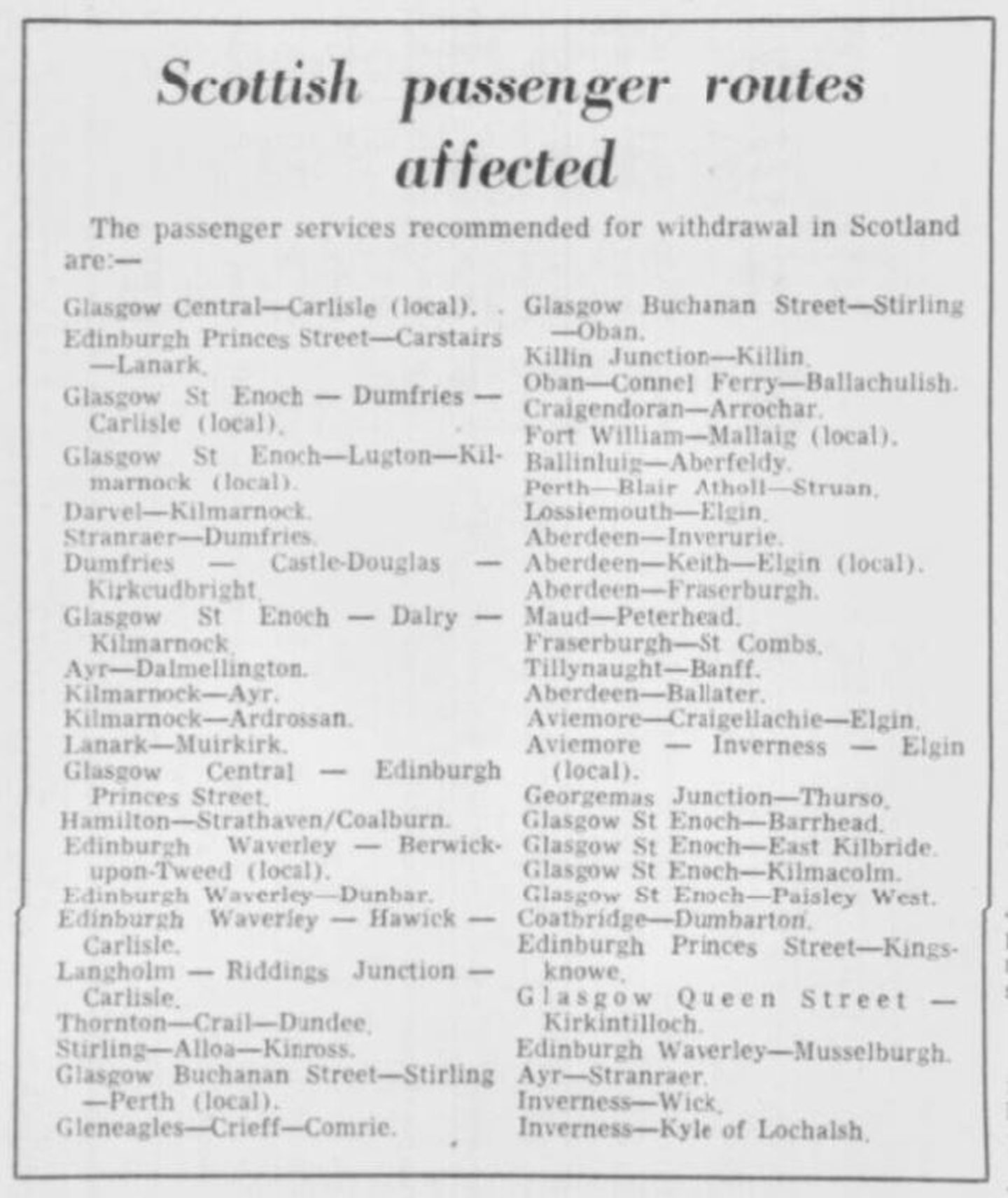

Beeching’s dramatic report proposed the decimation of the north-east railway network as part of cost-cutting measures.

The document identified 2,363 stations for closure across Britain and the withdrawal of 300 passenger services covering 5000 miles.

In Scotland this was 435 stations – representing 62% of stations in the entire country.

Beeching said the railways’ deficit would be eliminated by 1970 if his 15-point plan was implemented with “vigour”.

Inverurie Station was to shut by the end of the year.

Inverurie vowed to ‘put up stiff fight’ for station

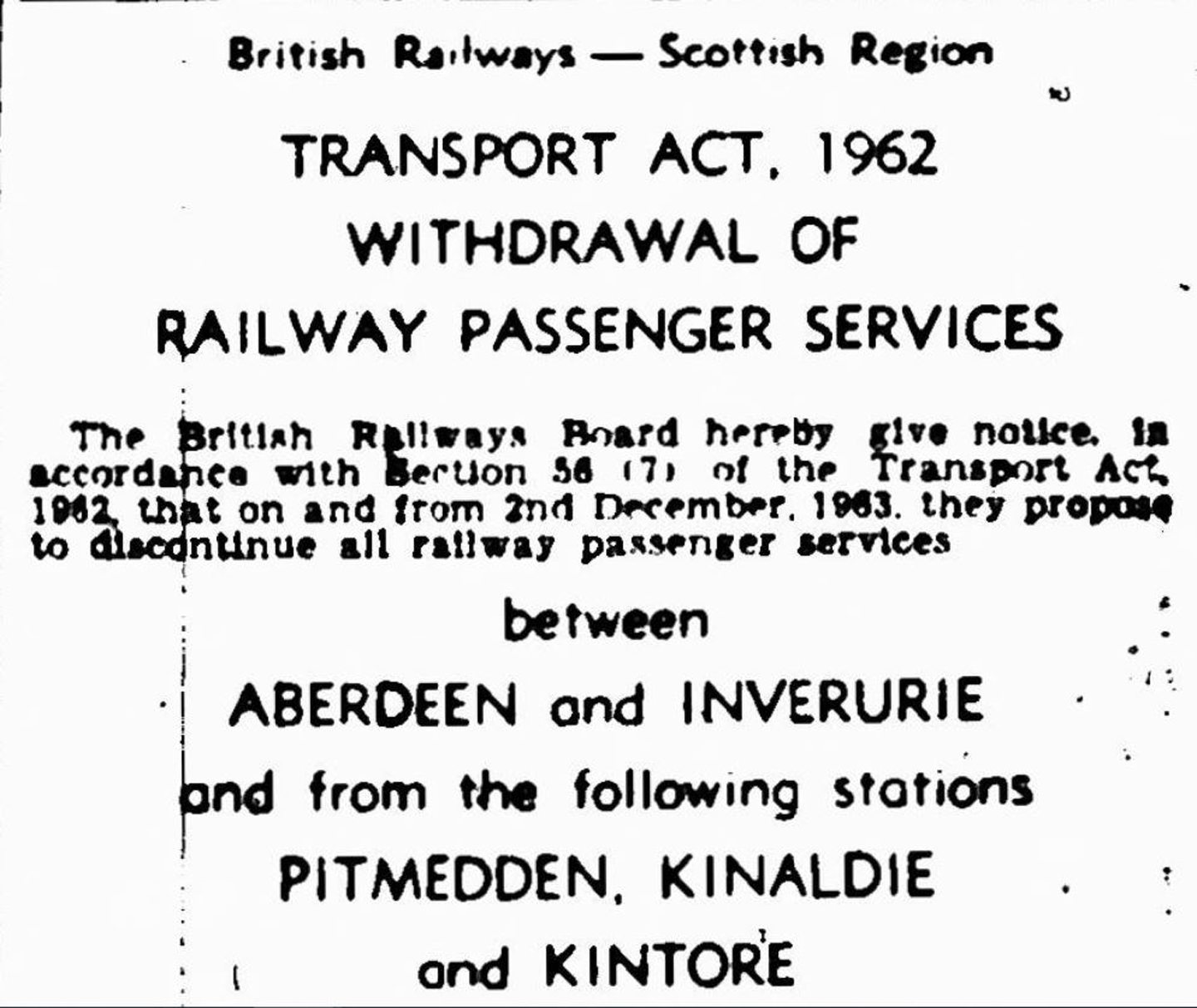

It was one of 88 stations scheduled to close on December 2, 1963.

But opposition to Beeching’s report quickly gathered strength across the north-east.

Instantly, the town galvanised itself to fight for Inverurie Station.

A similar protest in Buchan secured a stay of execution for rail routes to Peterhead and Fraserburgh.

It was reported that Inverurie “put up a stiff fight”. The town council met Scottish Secretary Michael Noble to pass on their desperate plea to the Minister of Transport.

John Watt, Aberdeen secretary of the railmen’s union, said: “We are not going to take this lying down.

“We will fight this tooth and nail and will encourage people living in the area affected to register their protests.”

With just six weeks from September 2 to register their concerns with the Transport Users’ Consultative Committee for Scotland, battle commenced.

People power and admin overload saw station closure delayed

The month before the December deadline, the Buchanan Report ‘Traffic in Towns’ was published.

It was an influential analysis of the long-term effects of urban transport and planning policy, and advocated the use of public transport.

Transport minister Ernest Marples was non-committal and said “all relevant information would be considered”.

But Inverurie Station was granted a reprieve, and not because of transport analysis.

It was people power.

Rail users across Scotland had lodged so many objections with the Transport Users Consultative Committee that it was completely bogged down with paperwork.

A press report revealed: “The machinery has been so effectively clogged that it seems unlikely any closures can take place before the New Year.”

1964: Station played ‘vital role’ in life of Inverurie’s community

But the battle was not won, merely delayed.

In early 1964, Inverurie councillor James Stephen argued the perceived low volume of traffic on the railways reflected a lack of advertising on British Railways’ part.

But train usage at Inverurie was an estimated 4,500 passengers a week – only about a fifth less per week than today.

Inverurie Bulb Farm and Inverurie Paper Mills also made great use of passenger trains.

Town clerk Mr Kellas said: “Inverurie passenger station plays a vital role in the social and industrial life of the community.”

Local farmer John Sorrie said the loss of Inverurie Station would directly impact his expanding business supplying day-old chicks to customers.

As Britain’s most northerly racehorse trainer he also said the withdrawal of services at Inverurie would “create problems sending horses to race at English meetings”.

Meanwhile the National Farmers’ Union voiced objections to the closure of the Inverurie-Oldmeldrum branch line, feeling it hadn’t exploited its potential in freight.

And even the council raised concerns about more traffic that would be “thrown onto roads, which were in winter not infrequently blocked or in a dangerous condition due to snow and ice”.

Years of uncertainty about Inverurie Station were finally over by 1966

But come September, Ernest Marples consented to the closure of Kintore, Kinaldie and Pitmedden – and Inverurie’s fate still hung in the balance.

Trains stopped at the three stations for the final time on December 7, 1964.

People living in Pitmedden faced losing an hour’s work to get home at night because the replacement bus service was inadequate.

On March 25, 1966, a new wave of announcements came from British Railways.

But crucially, a small clause at the bottom read “the board have decided for the time being to retain Inverurie Station”.

A strong case had been made for its retention – railways were the lifeblood of the town.

Inverurie Provost Alex McNab said: “It means a lot to the burgh. We fought hard for this at the Transport Users’ Consultative Committee inquiry and we were very hopeful.

But another 33 stations were not so lucky.

After a further survey of rail patronage in the north-east, British Railways announced more passenger service withdrawals.

Among those 33 proposed to be closed were stations at Kittybrewster, Dyce, Pitcaple, Oyne, Insch, Kennethmont, Gartly, Rothiemay, Cairnie Junction and Grange.

But Inverurie’s woes didn’t end there; its status as a railway town would disappear at the end of the decade with the locomotive works’ closure.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation