For 65 years, Aberdeen University’s Student Union was a legendary venue and a spiritual home for generations of students.

When the new student union opened in 1939 it made history as the first in Scotland to merge men’s and women’s unions.

It was also the first time in Scotland that the university court and senate had representatives on a student committee.

Directly across the road from Marischal College, it was an important base and handy watering hole for generations of students.

In later years the cavernous venue had capacity for 2,000 students across its six bars and cafeteria.

Many former students likely spent some of the best times of their lives at the Gallowgate union.

As the 2000s approached and lectures moved from Marischal College to the King’s College campus, it was the university’s last stronghold in the city centre.

But as attendance dwindled and costs rose, the union closed forever in 2004.

Aberdeen University’s new union delayed by disgruntled tenant

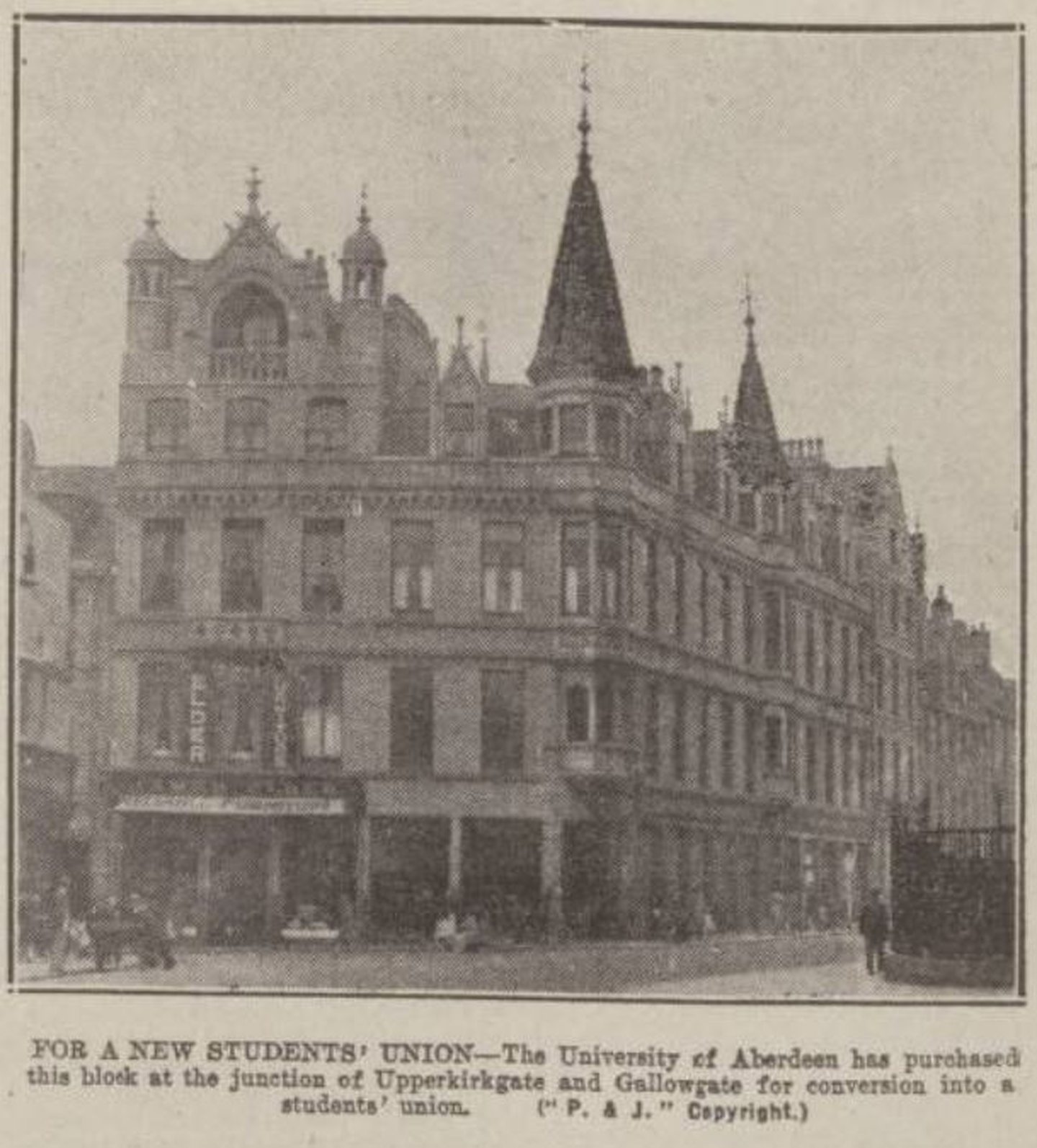

The University of Aberdeen acquired the prominent buildings at 11 Gallowgate/2-4 Upperkirkgate in 1929, with a view to building a new students’ union.

Until that point, the men’s union was at Marischal College, while the women’s was located on Skene Terrace.

But both were to be brought under the same roof for the first time.

Work finally got under way in 1934, but it was delayed by an unimpressed tenant, Alexander Mackie, who refused to leave a building which was due to be demolished.

He was less than keen to give up his house within the property in return for accommodation a few doors down at number 9, which he considered inferior.

In 1936, when the university took Mr Mackie to court he claimed the top floor flat would be bad for his wife’s health, that he couldn’t sleep under skylight windows and that rats had been spotted at the entrance.

JB Nicol, the architect carrying out the students’ union development, said the whole project was being held up by Mr Mackie.

New students’ union cost £34,000

Eventually the two parties came to an agreement and his removal fees were covered by the university.

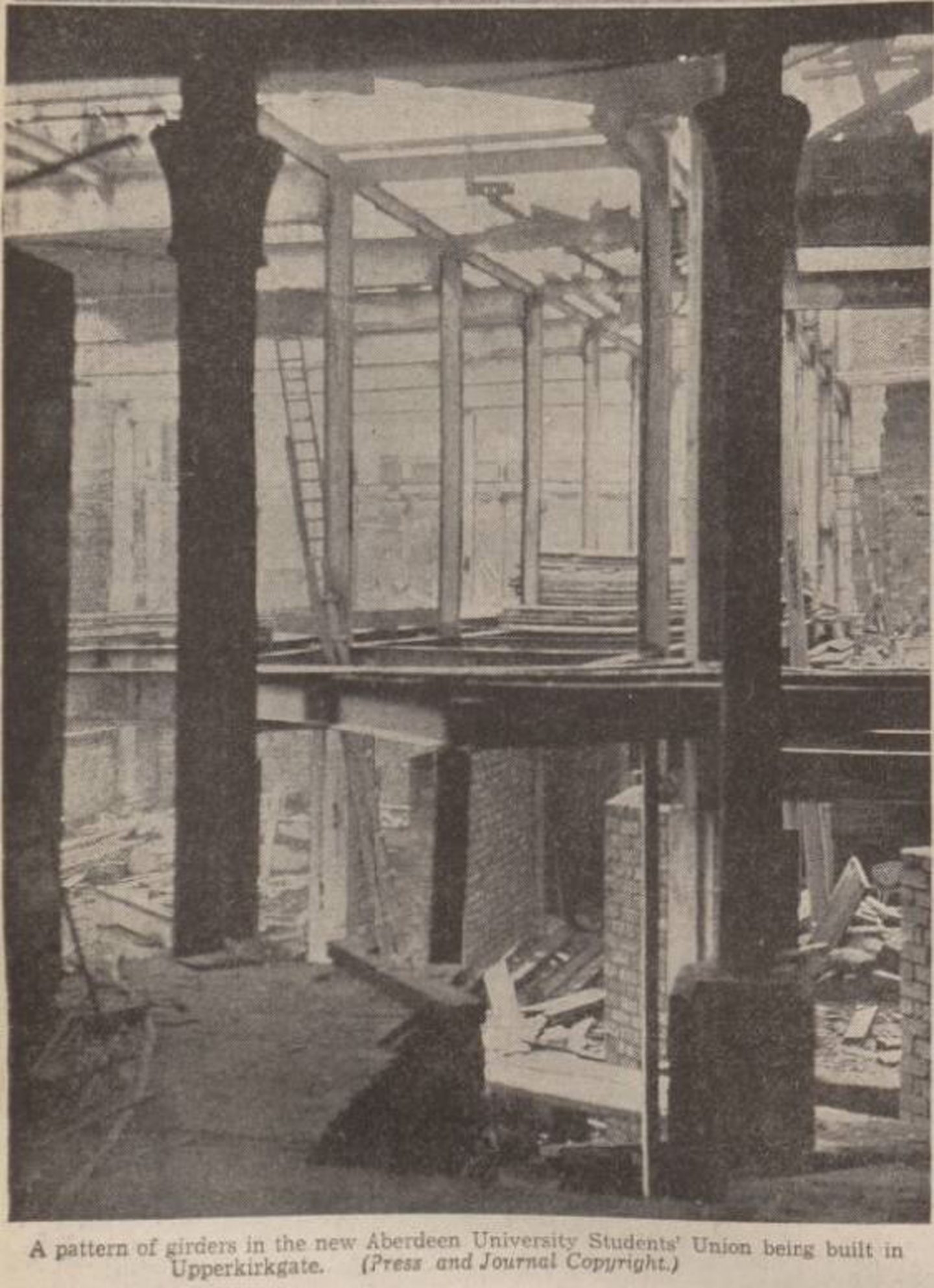

The ambitious project finally commenced in August 1936, the late 19th Century frontage was to remain unchanged, but that external wall was all that would remain.

On the outside, the only discernible difference was that some of the existing windows were turned into doors.

But behind the facade, great changes were being made at a cost of £34,000.

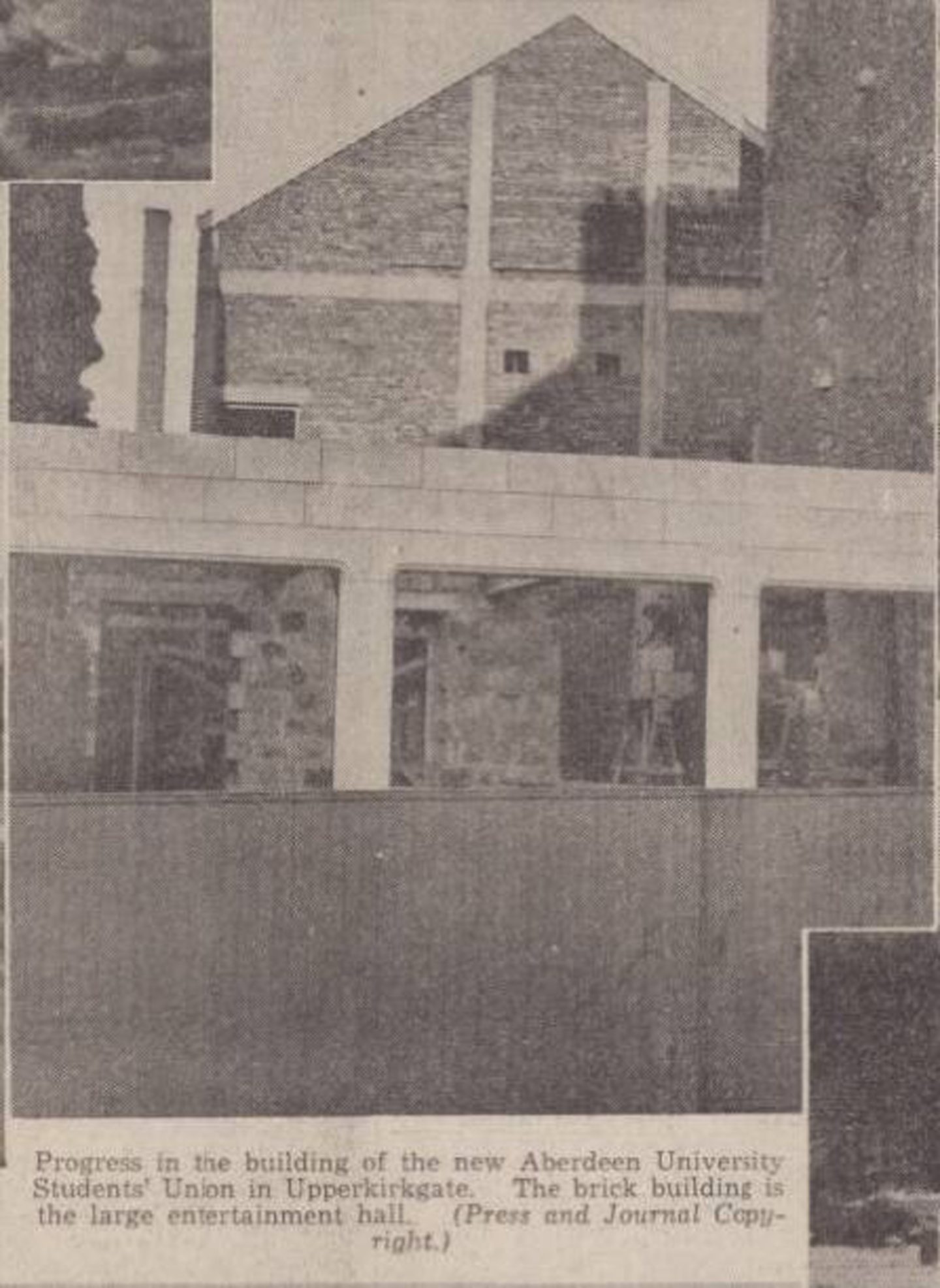

The whole interior was reconstructed, while the exterior section being rebuilt in Gallowgate was designed to ‘harmonise’ with the existing Victorian building.

The university said it was to be a “magnificent structure” four storeys tall.

New union had all the mod cons

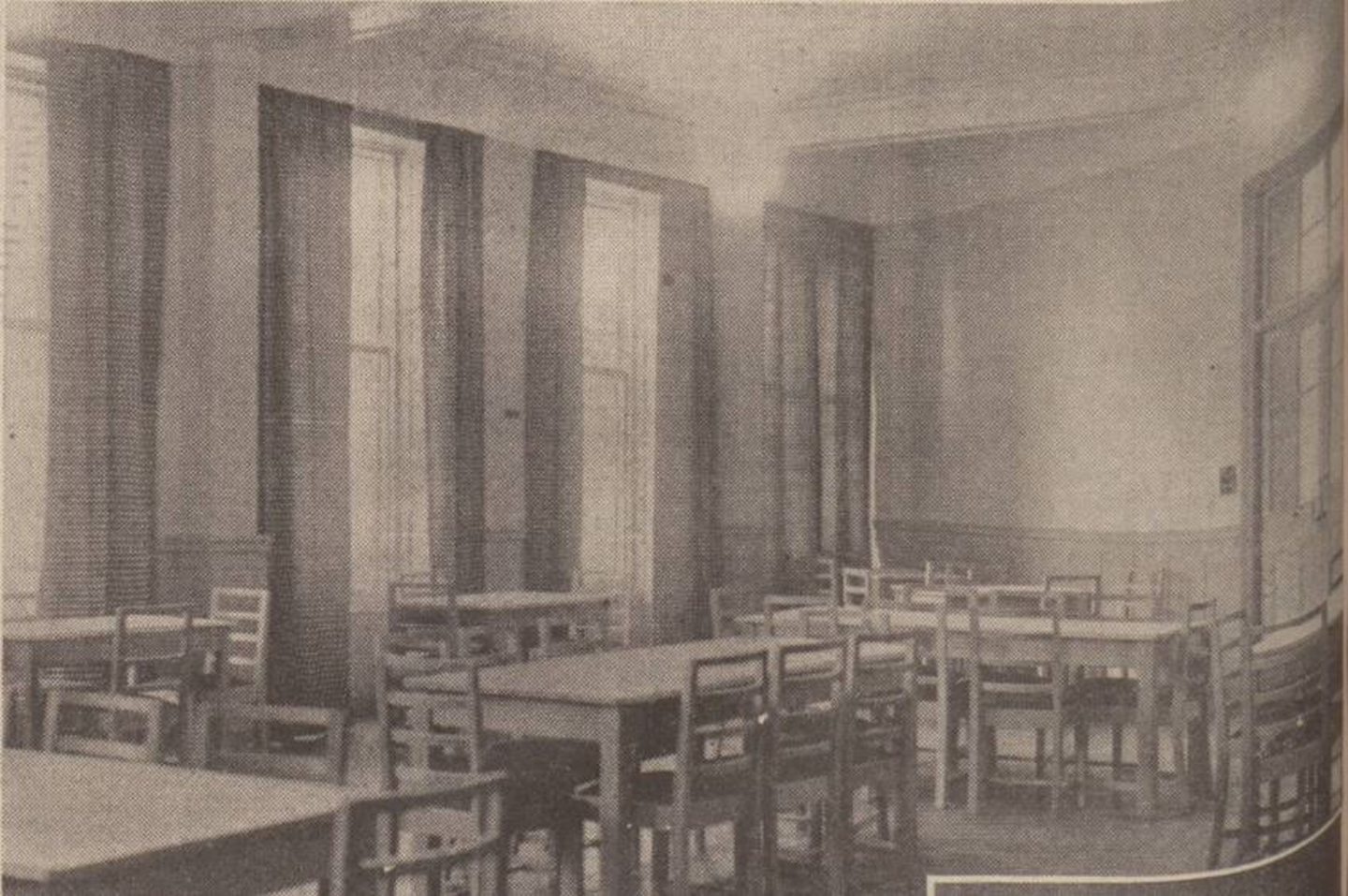

On the ground floor it was proposed to have committee rooms, lounges, card rooms and a library.

The upper floors had a large men’s union facing Upperkirkgate and women’s union overlooking Gallowgate.

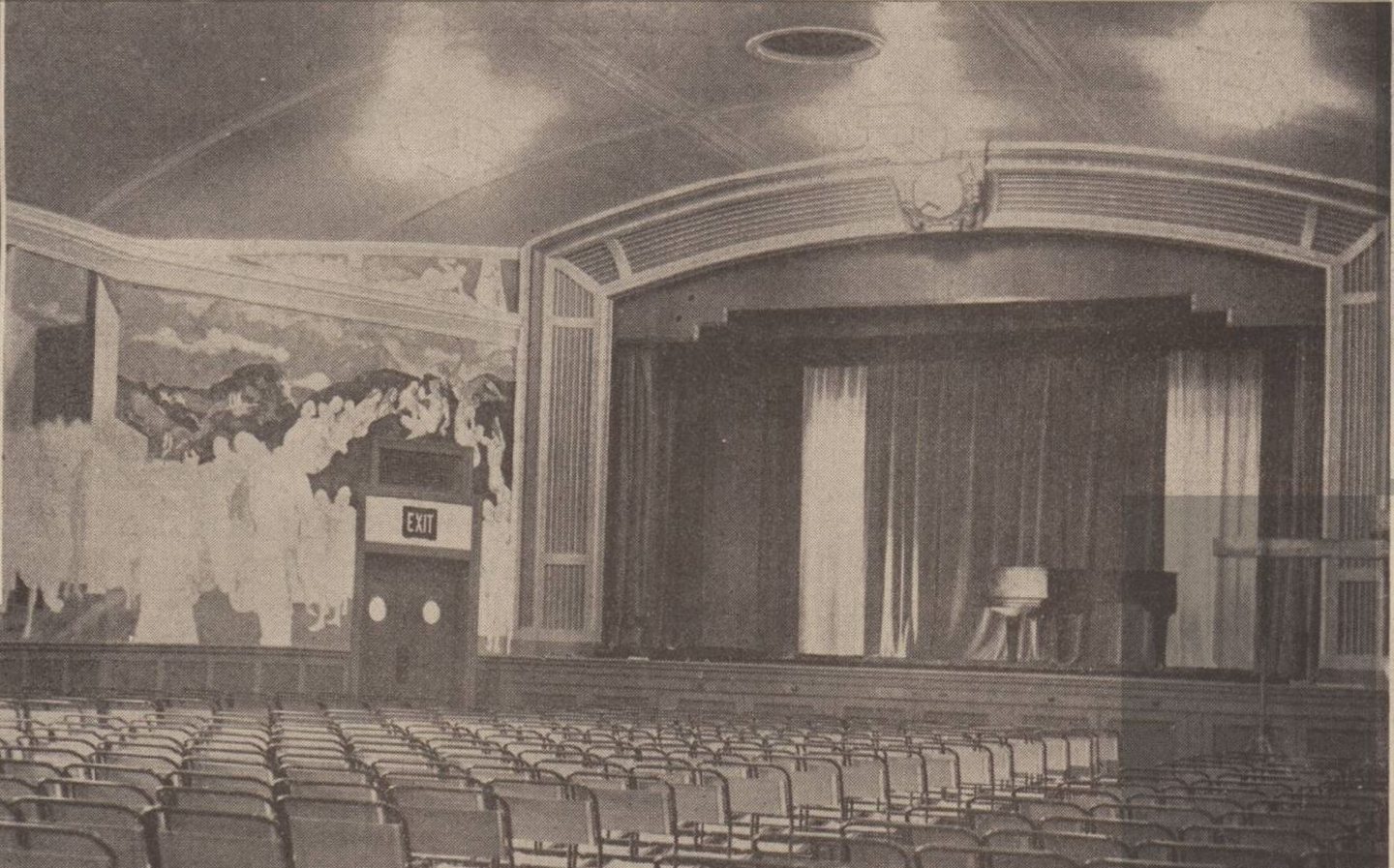

There was also a vast debating hall equipped with a stage and dressing rooms, a lounge, and billiard room with space for six tables.

What was a colossal project in the city centre neared completion in 1938 and a manager was appointed from Glasgow.

The post was given to Alec McKenzie, a First World War veteran, who had been a business secretary.

‘It is not buildings that make a university. It is men and women’

And on January 25 1939, the new students’ union opened with a procession from Marischal College down Broad Street.

The “handsome” new building was officially unveiled by university principal Hamilton Fyfe.

He paid tribute to the students of 30 years before who had worked hard to establish this new union.

Principal Fyfe said they had an “admirable building” but “building the real union had just begun”.

He added: “It is not buildings that make a university. It is men and women.

“A university is a place where old knowledge is stored and new knowledge is accumulated.”

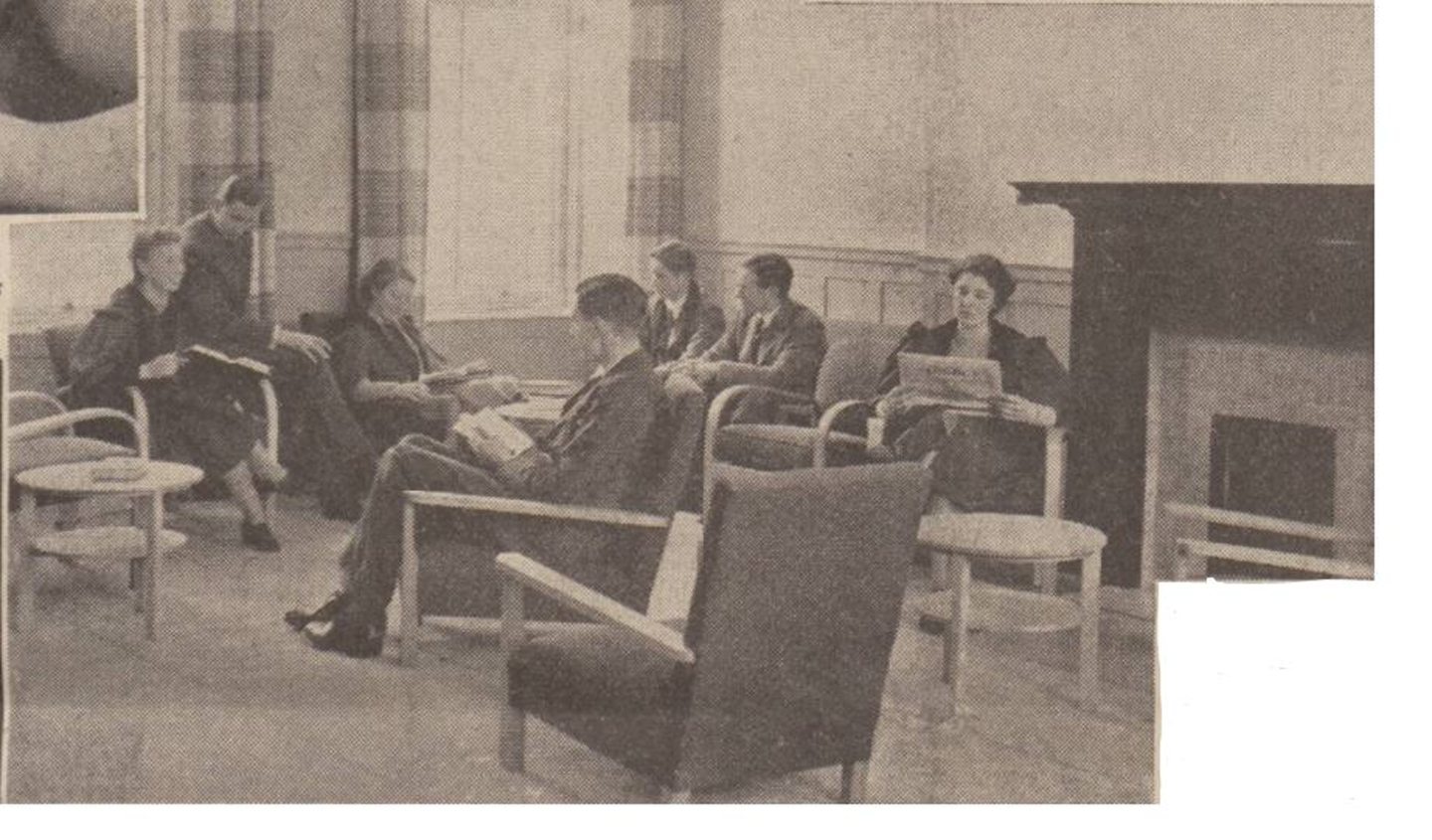

He placed a great emphasis on socialising and fellowship with peers.

Principal felt socialising was important part of university education

Principal Fyfe explained the union was there to help provide a full education.

He added: “It is my hope that in this union, the large population of the university will rub shoulders and exchange ideas, not only in the debates and discussions and dramatic performances, but also in casual informal conversations in armchairs over cups of tea or, it may be, mugs of beer.”

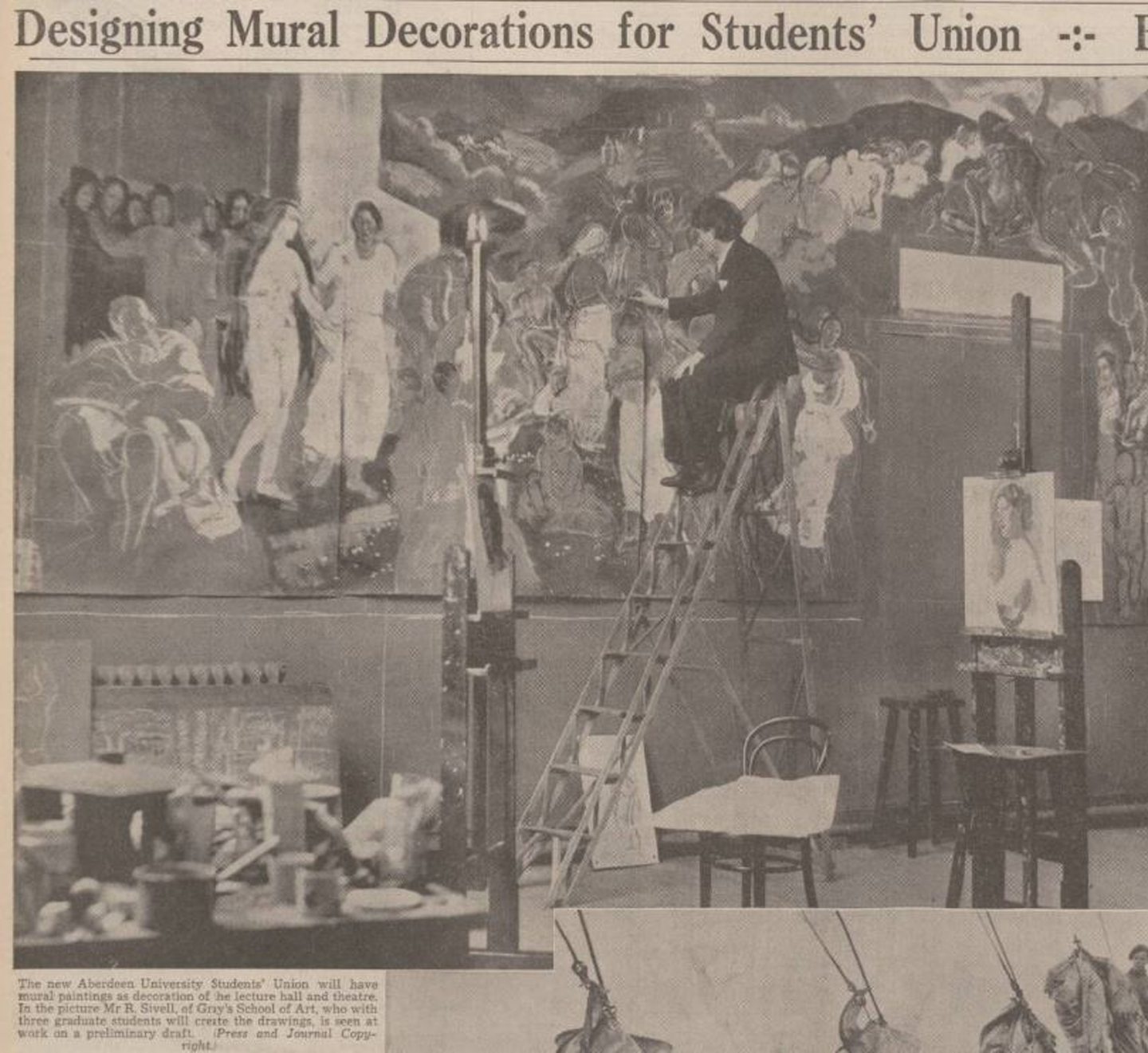

The concert hall, which formed the centre of the venue, was still being decorated with impressive murals by art tutors and their students.

Although the male and female students had separate entrances and separate lounges, there were common rooms and shared dining spaces to socialise and share wisdom.

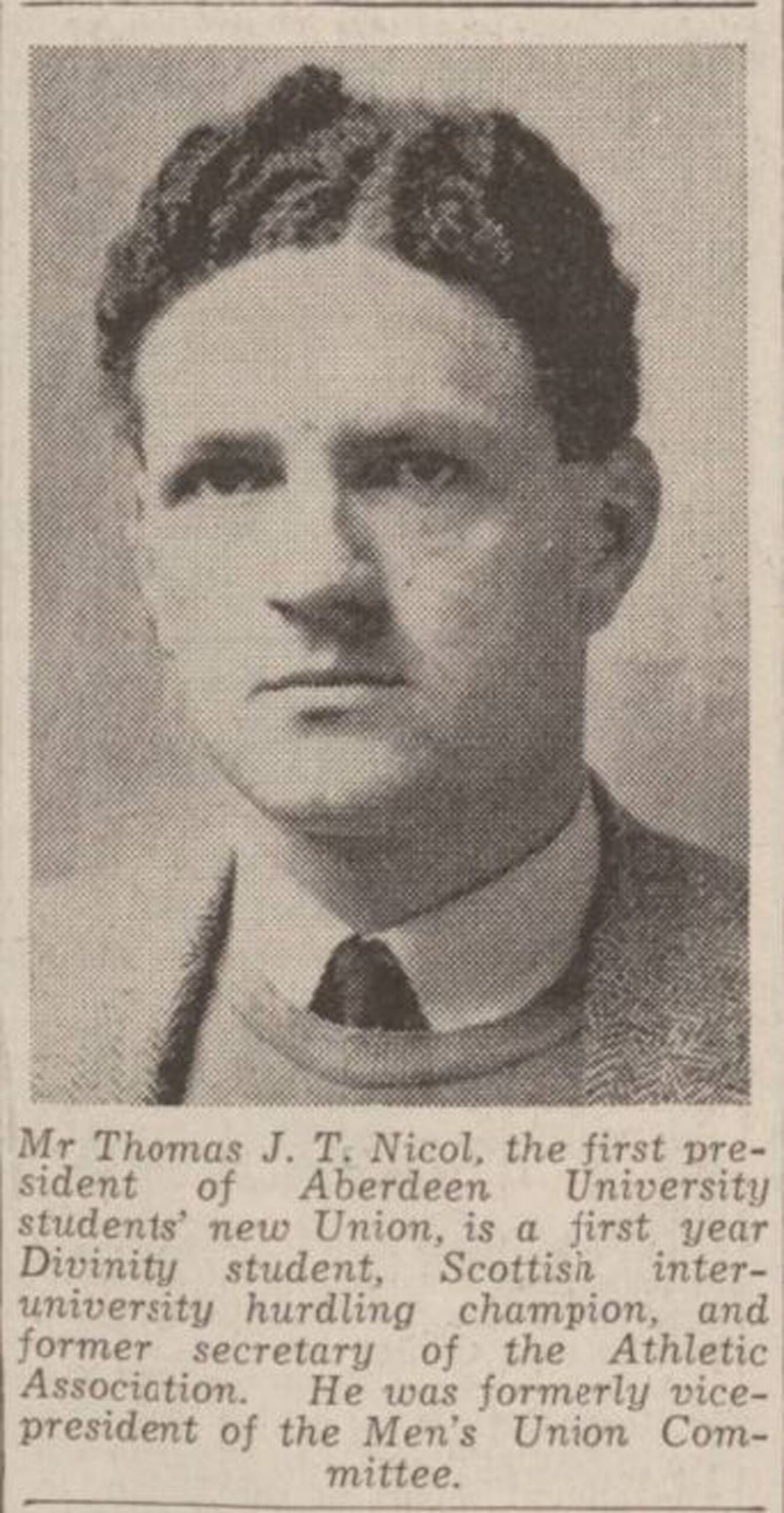

The joint union’s first ever president was appointed, prominent university athlete and divinity student Thomas Nicol.

He would go on to serve as an army chaplain in the war, later becoming minister to the Royal Family at Crathie Kirk as the Rev Dr Nicol.

Gray’s School of Art lecturer designed murals for union

But the union wasn’t quite finished – a series of large murals in the concert hall covering 1,300 square feet, started in 1938, were still a work in progress.

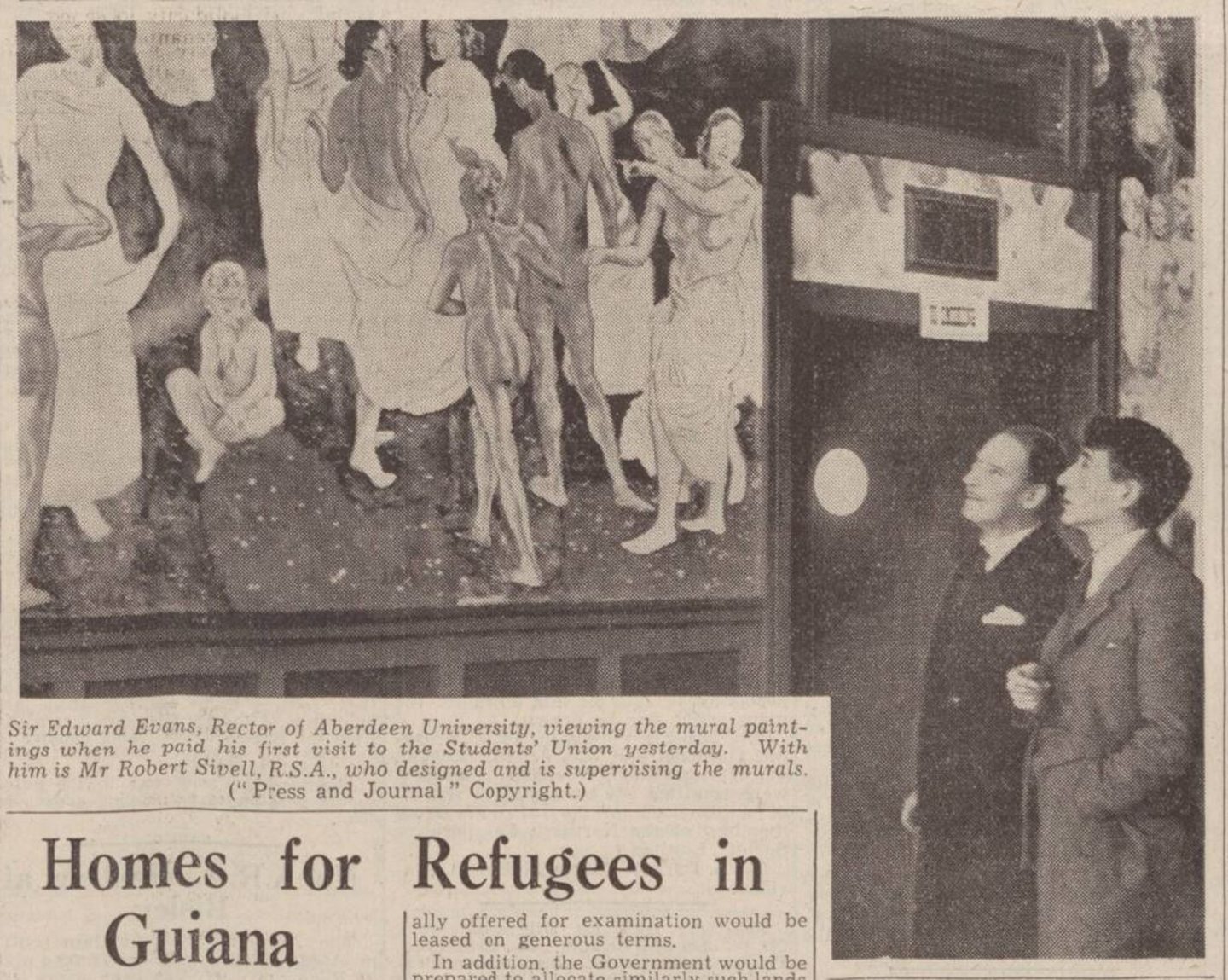

The exquisite murals were designed by renowned Scottish artist and head of painting at Gray’s School of Art, Robert Sivell, in the Italian renaissance style.

They were painted by two of his students, Alberto Morocco and Gordon S Cameron, who both went on to become distinguished artists in their own right.

Anybody who frequented the union in its heyday will remember the distinctive murals which depicted the journey of life from creation to death.

In one of the earlier parts of the work, Sivell included figures of people who helped the new union come to fruition.

The full-length and life-sized figures conveyed Principal Fife and Professor Ferguson, who was Dean of the faculty of arts, standing beside a fountain in academic garb holding scrolls.

Two other men “who worked hard and earnestly in the cause of the new union” were painted at the other side of the fountain – past president Lesley Eddey and new president Thomas Nicol.

WW2 disrupted painting of murals as students fundraised for war effort

But the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 disrupted work on the mural.

Students had been organising a fundraising concert called ‘Hits and Misses’ the following month to pay for the ongoing mural project.

But they decided the concert proceeds should be donated to the Red Cross instead as part of the students’ contributions to the war effort.

During the war, Sivell was part of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee to carry out work for the Imperial War Museum.

Officially, the purpose of the committee was propaganda and to capture scenes of the war at home and abroad.

But many artists and writers were killed during the First World War, and it was hoped “by keeping artists usefully employed the scheme might prevent a new generation of British artists from being killed”.

Acclaimed mural was finally finished in 1953 – 15 years after it was started

It wouldn’t be until 1953 that Sivell’s mural was finished, with Gordon S Cameron having painted most of it.

It was described as Sivell’s magnum opus – to great national acclaim.

One panel even depicted university students’ studies being disturbed by the blitz.

The late Sir William Oliphant Hutchison, painter and president of the Royal Scottish Academy, said it was “the greatest mural painting carried out in Scotland during this century, and perhaps any other”.

The bar in the union was named Sivells in his honour.

But in later years, unappreciative students treated the mural panels like regular walls, covering them in posters, tape and drawing pins.

In 1988, students wanted to dispose of the murals when the “austere” hall was transformed into a three-level wine bar.

But the university saved the murals and they underwent restoration work in 1993.

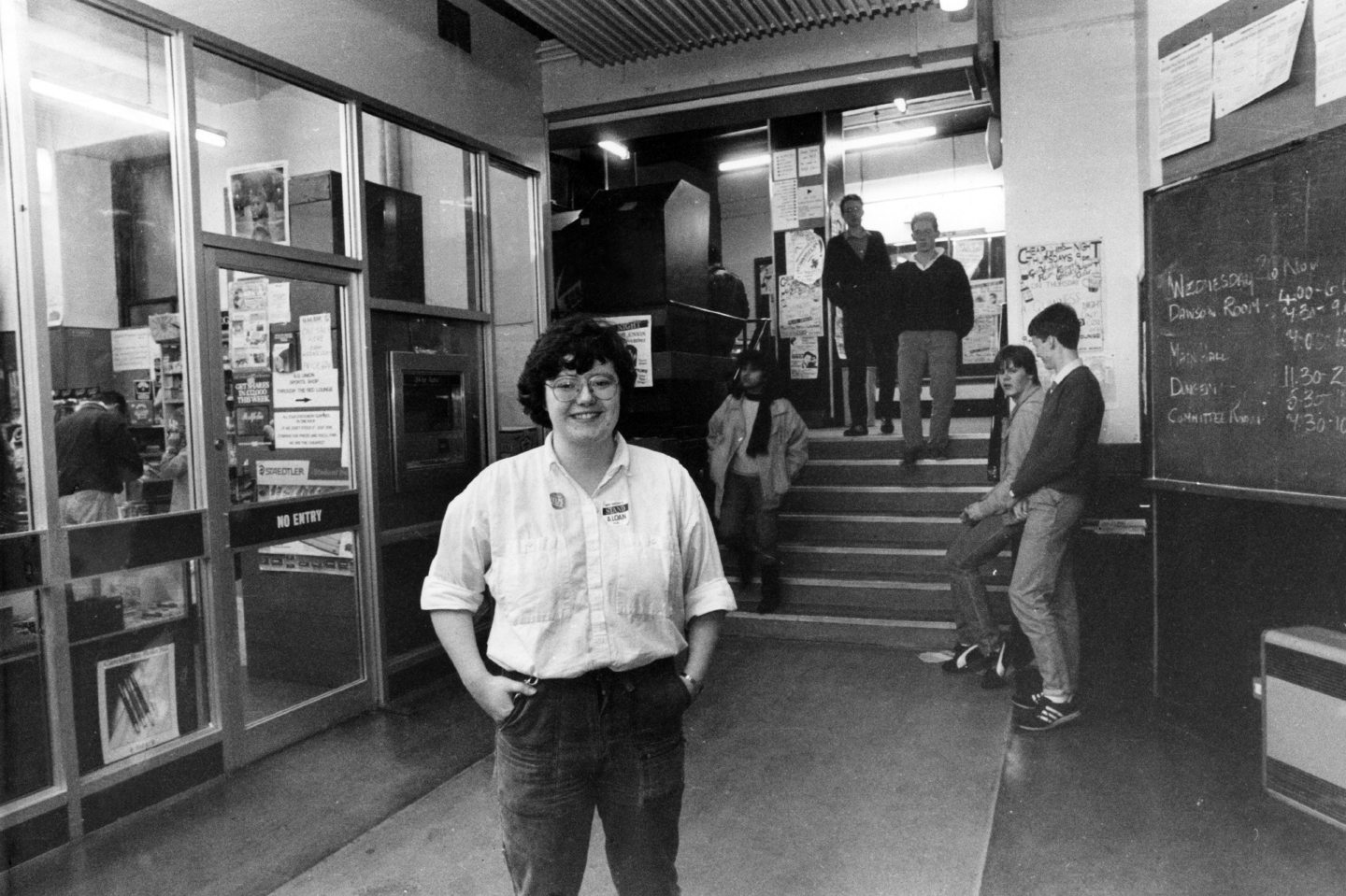

With six bars and capacity of 2,000, union was popular city haunt

Before the union’s hall was redesigned, generations of students enjoyed theatre performances and dances there.

As well as Sivells, students also enjoyed cut-price booze at The Elf, Factory, The Dungeon, and Associates. Although it was often so busy, a lot of the night was spent queuing to get in.

The Dungeon, the underground bar, was also a popular venue to watch bands and gigs, or partake in quiz nights.

Thin Lizzy played the student union in the ’70s, and John Peel took his roadshow there in 1982.

If you knew a student (or could bribe one) you could be signed into the union to enjoy cheap nights out and, in the 1980s anyway, pints at 60p a pop.

In the 1970s and ’80s, it wasn’t unknown for skint students to sign offshore workers into the union in return for payment.

Aberdeen student union is gone but not forgotten

Some former students, if they can cast their minds back far enough, might even remember the union’s popular, friendly senior porter Jack Nairn, fondly nicknamed ‘Union Jack’.

Jack started as a porter at the union in 1940, and was known as the man who introduced thousands of students to university social life.

When he retired in 1973, students past and present held a whip-round to raise £500, and hosted a sherry reception in his honour.

But by the late ’90s, the union suffered fierce competition from nightclubs like Amadeus and drinks promotions elsewhere.

The union limped into the noughties, but there was still shock when the closure was mooted in July 2003.

In December, the union’s opening hours shrank to Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings.

And the following spring, Aberdeen University blamed “a downturn in business levels within the bar, entertainment and catering operations”.

Twenty years on from its closure, the spiritual home for generations of Aberdeen University students lies forgotten. Part of it is now a Starbucks, the rest lies empty.

Sivell’s nationally-celebrated murals, although covered up, are shrouded in dust and darkness.

A handsome building, which once echoed with decades of debates, dances, live music and laughter, now sits in silence.

More Past Times stories

The death of a regiment: Remembering the amalgamation of the Gordon Highlanders 30 years ago

Slum demolitions, developments and the Denburn: Photos of September days in Aberdeen over the years

Art Deco Aberdeen: A closer look at 12 surviving landmark buildings

Conversation