Julie Allan’s family story is that of legend, thanks to her father Calum MacLeod and the famous Raasay road he painstakingly built by hand.

But behind the fabled history of Calum’s Road lies a tale of desperation, determination, and heartache.

From an annexed community fighting for its future, to the separation of his daughter from the family home, we’ve spoken to Julie about her dad, the years she spent boarding in Skye, and what she believes is the true motivation for that now famous Raasay road.

Homecomings were few and far between during Julie’s school years

In 1962 everything changed for the MacLeods of Raasay.

Calum and Lexie’s only daughter Julie was denied the right to remain in Torran School where her mother could teach her. High school – in Portree – beckoned.

Attended by children from Skye, North Uist, and Harris, unlike some other children making the move, it presented a great sacrifice for families from the Island of Raasay’s northern townships.

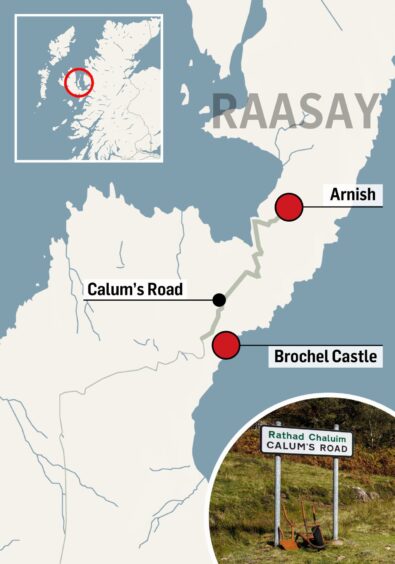

Living in Arnish, Julie would have to board in a hostel all week while she attended school, but unlike her peers, she would rarely be able to return home.

‘I was taken against my parents will, they wanted me at home’

Though Raasay is “a stone’s throw” from Skye by boat, getting to Arnish and back between sailings was impossible. Not least because there was no road connecting the south of the island to the north.

After the sailing and a hired-car ride to the Brochel Castle area, Julie would face another 45 minute walk with her bag, to their home, in all weathers.

“It was pointless. There were no steamers on Fridays. If I went on the Saturday, by the time I got there I would have about half an hour and then would need to turn and come back as there were no sailings on the Sabbath.

“This meant when all my school friends were going home at weekends I had to stay.

“Which doesn’t sound so bad until you realise it meant I was basically taken – against their will – from my parents at 12, and would never truly return home,” said Julie.

‘Those years changed me,’ Julie said

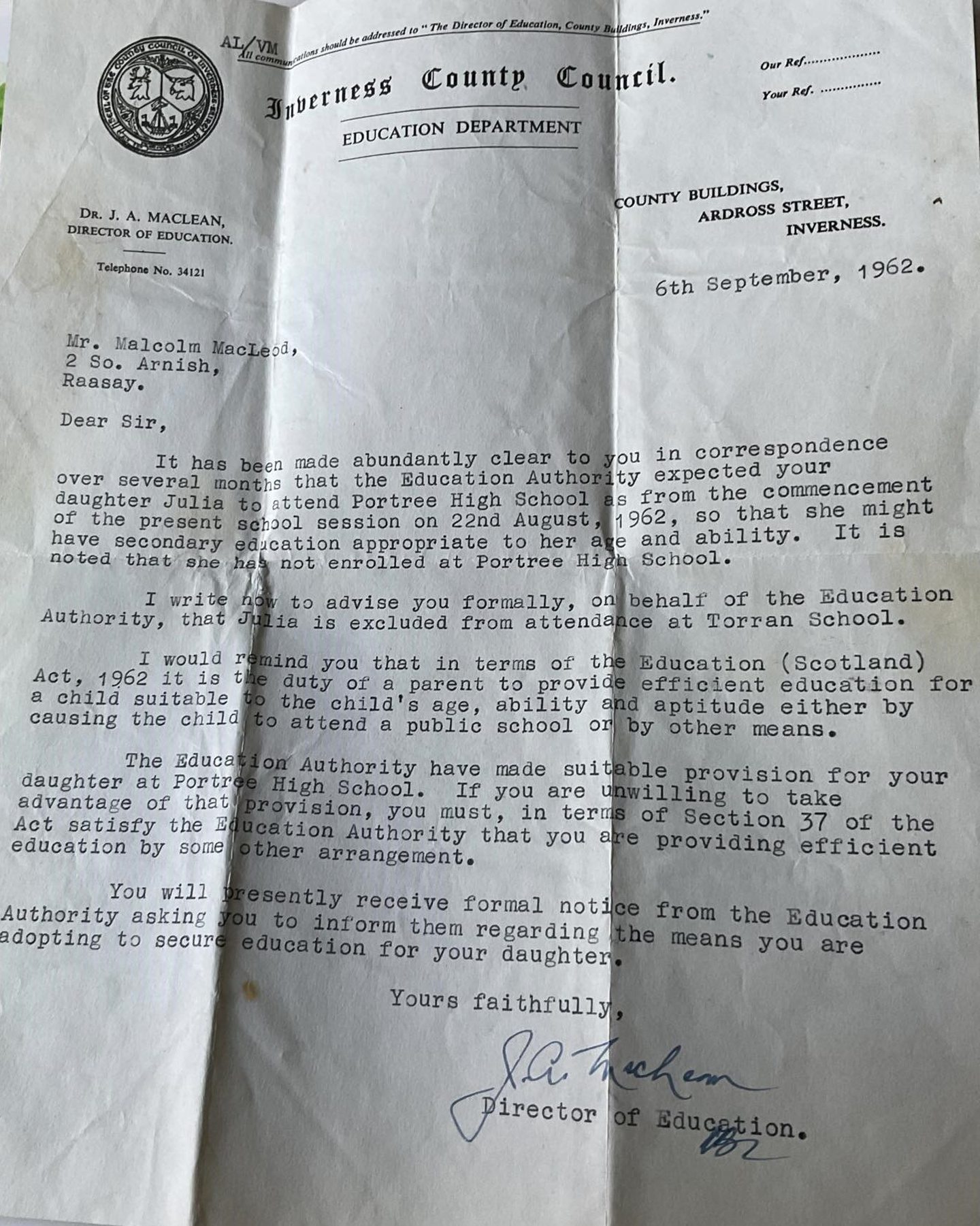

Letters between Calum Macleod – the postman, former lighthouse boatman, and lighthousekeeper of Rona – and Inverness County Council allude to Calum’s strife with the local authority.

“It has been made abundantly clear to you in correspondence over several months… that your daughter Julia is expected to attend Portree High School… from 22nd August 1962.”

Later, the same letter spells out that Torran School, where Julie’s mother was previously tasked with teaching children up to the age of 15, would not be an option.

“On behalf of the Education Authority,” the director of education writes, ” Julia is excluded from attendance at Torran School.”

“I was just a baby. I have grandchildren that age now and I can’t imagine them being forced away into a hostel, not allowed or able to come home at 12.

“It was only during holidays that I saw my parents.

“Those years changed me.”

Life-changing letter for children of island communities

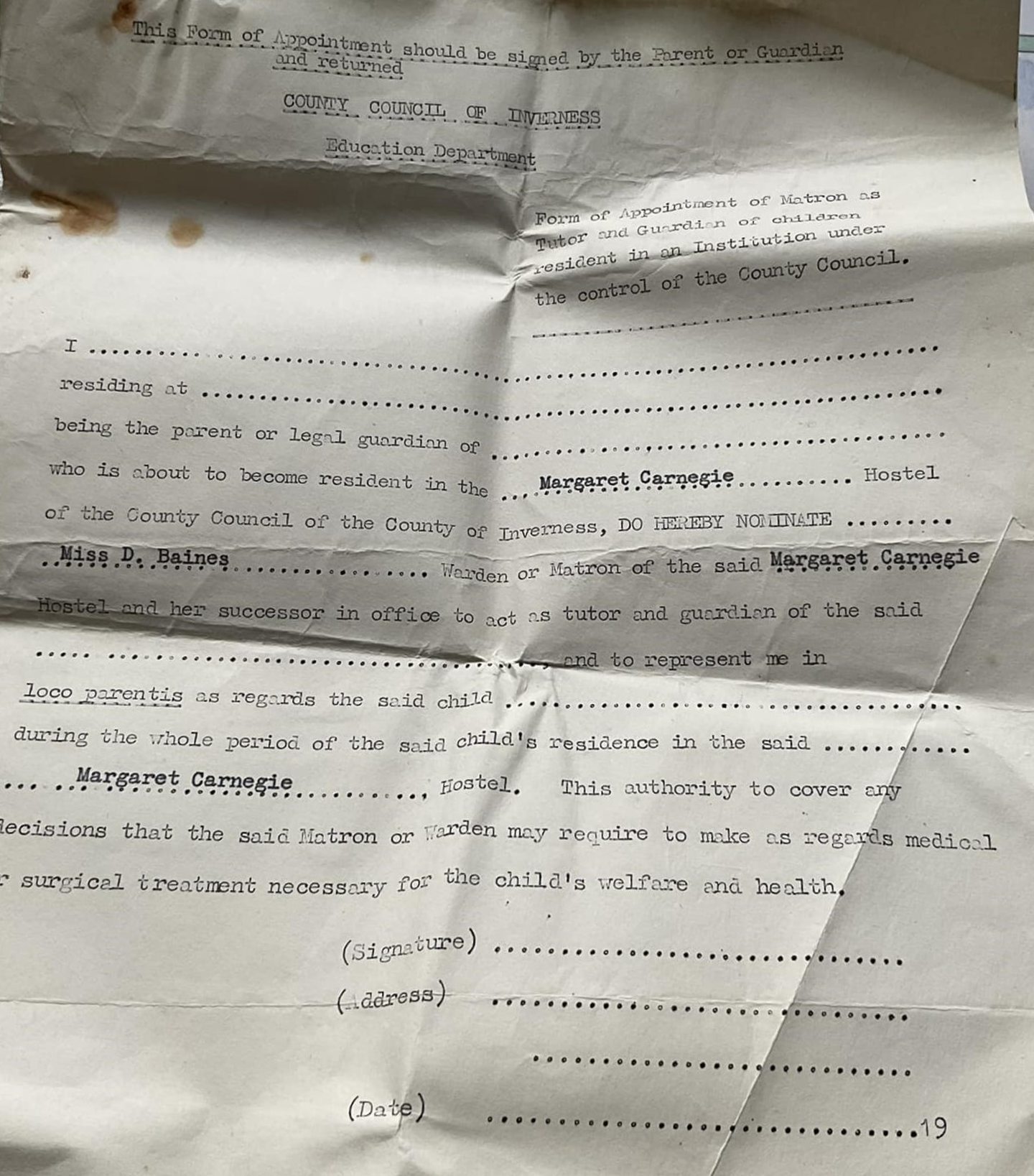

Julie was a boarder of the Margaret Carnegie Hostel for four years until she left school in 1966.

When she recently shared an official letter about her accommodation on social media, where the hostel was described as an institution, it received mixed responses.

“This was the letter that changed a lot of lives, “Julie, who is married and lives in Fife, wrote.

“Hated every day I was there,” commented one person. While many others said they enjoyed their time at the school and in boarding accommodation.

‘Losing Gaelic is a huge regret’, says Calum’s daughter

The seventh girl to move into her dorm, Julie found it hard to adjust, having only lived with her mother and father. There were no others from her primary school in the dormitory with her.

“Lights out” was 9.30pm and any talking once in their “standard issue army-style metal beds” resulted in 100 lines before breakfast. She described life at the hostel and daytime at school as “living and dying by belts and bells”, noting there was “a bell for everything.”

“It was awful. I hated it. The matron was kindly and the cook was kindly but I found school really tough.

“And although I had to speak in English for primary school already, being away from home and never being taught in Gaelic… it was the beginning of the end for me and the Gaelic language. Which I deeply regret.”

Raasay’s lack of roads sparked Calum’s building legacy

Back at home Calum and Lexie were also impacted by their daughter being away.

Missing their only child, who was also “another pair of hands at home on the croft”, Julie’s leaving coincided with Calum’s history of petitioning the council for better infrastructure on Raasay.

The couple were acutely aware that if a road existed they would have been able to see their increasingly unhappy daughter more than a couple of times a year.

“School was hardening me. I’m still affected today and I’m 74. More than 60 years later,” Julie added.

The roads – or lack of them – were already a bugbear of Calum’s. From 1949 to 1952 he and his brother Charles constructed the track from Torran to Eilean Fladday, over three winters. They were paid £70 a year between them, by the local council.

The legend of Calum’s Road begins

By 1964 – two years into Julie living away from home – and after unsuccessful campaigning and several failed grant applications by residents of north Raasay, Calum decided to build the road from Brochel Castle to Arnish himself.

He bought a copy of ‘Road Making & Maintenance: A Practical Treatise for Engineers, Surveyors and Others’ for half a crown, and started work.

“It took more than a decade, so it was too late for me,” Julie said.

Indeed, the one-and-three-quarter-mile stretch took from 1964 until the mid-70s to build, using just a shovel, pick and wheelbarrow, though initial blasting work was carried out by the Department of Agriculture.

Calum’s Road became the stuff of legend.

MacLeod invested blood, sweat and tears into his road

In 1990, on the event of a cairn being built in his memory, a Scotsman article described his feat of endurance.

“… hacked and hewn from rock and heather, peat and gravel, by one man, a pick axe, a hammer, shovel, boundless determination and not a little rage.”

Calum died in 1988, not long after completing the gargantuan task.

It was said of him that he was a crofter, a lighthouse keeper, a writer, a father and a husband, and thanks to his single-minded determination, he was able to accomplish what no one had done before.

Sadly, by the time it was complete, he and Lexie were two of only a handful of remaining residents of Arnish. Annexed by a lack of accessibility, most Raasay families moved south or off the island altogether.

Author’s memories of road-builder MacLeod

Such was Calum’s once-in-a-generation achievement, he and his road have been immortalised in song, books, film and plays.

One such author is Roger Hutchinson.

His book, Calum’s Road, had personal significance.

“I met him actually,” Roger told me. “I was working at the West Highland Free Press and in 1979 a notice was placed from Inverness County Council, considering surfacing Calum’s Road. So I went up there.

“He was quite some man. He didn’t stop driving it forward until an ambulance could get to the door for his wife.”

‘Julie’s unhappiness was the tipping point,’ says Roger Hutchinson

By the time Roger met Calum, Julie had moved away from the island permanently, but the struggle the family faced was still at the fore for Calum.

“Before the road you couldn’t get within two miles of their home with a vehicle.

“There were several cases where he would get his daughter and a classmate dropped at the road end. On one occasion they were caught in a blizzard at 13 and 14 years old. It was a terrifying experience for all of them.

“This was absolutely one of many factors motivating Calum but certainly his daughter being kept at a distance, knowing she was desperately unhappy, tipped him over the edge.

“And remember the road had a direct link to depopulation, and from being a teenager Calum had been petitioning the council to do something.”

‘My time on Raasay was cut short, and it still hurts to this day’

Now 74, Julie is happily married to Eric and settled with her family in Fife.

She has two sons but sadly lost her daughter almost four years ago.

Calum died in 1998 having been awarded the British Empire Medal “for maintaining supplies to the Rona light” and her mum, “Raasay Lexie” – Alexandrina Macdonald Macleod – passed away in 2001.

Recently uncovered documents have given the grandmother-of-seven cause to reflect.

“I think there’s still a deep sadness about it all. The reality for island families is that they do lose their children when university calls, or they meet and marry someone from the mainland. Our time in the small, close-knit, sheltered communities is limited.

“My time was cut even shorter… and it was a cut. I felt that cut and I feel it now. I lost those last precious years.”

After school, Julie moved to Wester Ross where she initially worked in a care home, before making “a big move” to Glasgow to begin nursing.

‘As far as I’m concerned my dad built the road for me,’ says Julie

“On the one hand”, she said, “it all made me very hard and streetwise. I vowed I would never be bullied again.

“Seeing very clinical, uncaring forms, brought the lack of compassion back.

“On the other, I know that there is a steely determination and resilience in our family.

“Just look at what my dad accomplished.

“I’m the daughter of Calum Macleod. And as far as I’m concerned he built that road for me.”

Conversation