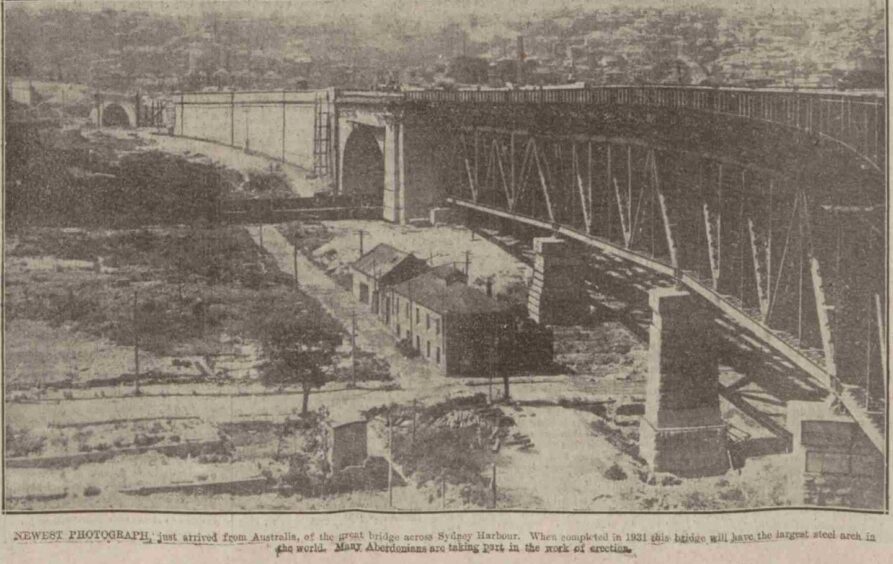

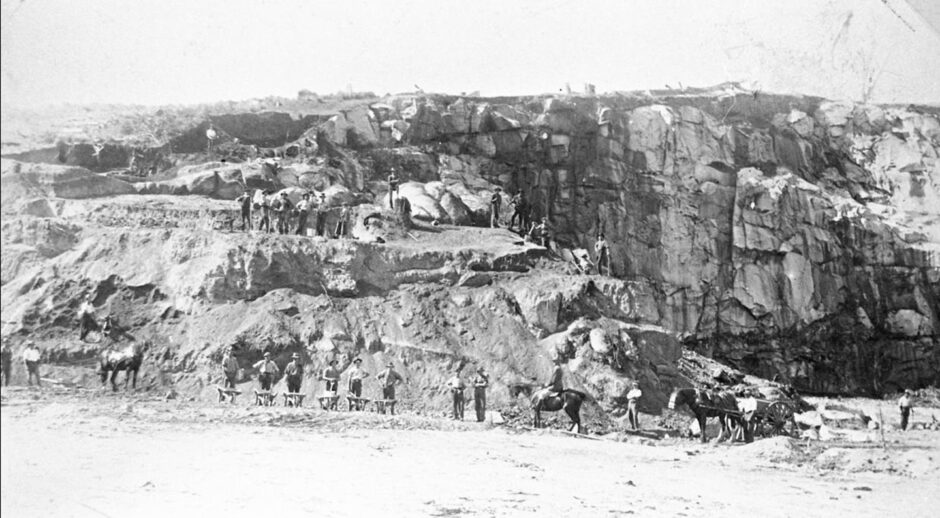

One-hundred years ago this month, the first shovels at a new granite quarry a few hundred miles outside of Sydney went into the earth.

It was a substantial event for a remote corner of New South Wales; over the next eight years, granite taken from the quarry would be used to build parts of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, one of the world’s most famous landmarks.

However, the opening of the quarry would end up having an even greater impact halfway across the world in north-east Scotland.

In need of skilled workers, the quarry would eventually pull in hundreds of Aberdeen stonemasons who travelled more than 10,000 miles to work there, upending their lives and those of the family members who came with them.

Meanwhile, Granite Town — the settlement attached to the quarry where the stonemasons and their families lived — grew from a handful of shacks to a bustling community with theatre productions and comedy nights put on by the transplanted Scots.

To mark the 100-year anniversary of the quarry’s beginnings, we delve back into the P&J archives to shine a light on this Australian outpost that touched the lives of so many from the north-east.

The story takes in the amazing people responsible for the unique settlement and of the workers and families that populated it who brought their own slice of Scotland to the New World.

And though Granite Town is no more, its history continues to have an impact, in both the descendants of those who ventured far from home to earn a wage, and from the Sydney Harbour Bridge itself, which nears its own centenary as a global icon.

An advert wrapped around some butcher’s meat

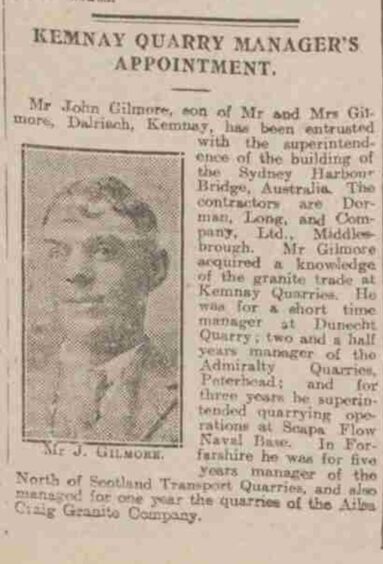

In November 1924, John Gilmore, an experienced stonemason from Kintore in Aberdeen, arrived at the quarry.

Mr Gilmore was the newly-appointed quarry manager. He got the position after his wife Mary — a school teacher in Kemnay — saw an advert on a piece of paper wrapped around some butcher’s meat and applied on his behalf.

Now, after jobs across the north-east and even in the US, Mr Gilmore had brought Mary and their eight daughters and one son to New South Wales on a whole new adventure.

His remit was to prepare and ready the quarry, which at that time was a “barren waste covered only with scrub and noxious weeds”, according to the local newspaper.

Gilmore, who died in 1965, was a steely character and he responded to his new role in Sydney with the same resilience that had caught the attention of his employers.

He was backed by the director of construction for the bridge, Lawrence Ennis, another Scot who had grown up in poverty in West Lothian and was determined to provide a better standard of living for his workers.

Ennis was responsible for the construction of Granite Town, motivated by his first-hand knowledge of poor housing and the ‘garden city’ model towns that were springing up in the UK.

“Ennis regarded Granite Town as a model township, in its own modest way,” says Bill Glennie, a former Scottish history teacher who has researched the ‘Quarry Scots’, as the stonemasons became known.

Leaving Aberdeen for Australia

Jim Fiddes, who has written a book, The Granite Men, about the history of Aberdeen’s most notable material, examined how scores of men departed from the north-east to Sydney.

He said: “The Aberdeen granite industry might have been in decline after the First World War but the expertise of its workers was still in high demand.

“It was in December 1926 that the Press & Journal reported that, earlier that year, 30 men had left the city to work on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“The paper noted that letters sent home from the men indicated they were more than happy with their working conditions — and that the wage they had signed up to had already been increased by 10 shillings a week.

“When a representative from [bridge builder] Dorman Long came to Aberdeen, he received almost 250 application forms and the first party of workers left Aberdeen in February 1926 with another group following them in May.

“Unlike most of the granite men who had previously gone to work in North America, this group took their families with them and children were born in Australia, who later moved back to Scotland with their parents.”

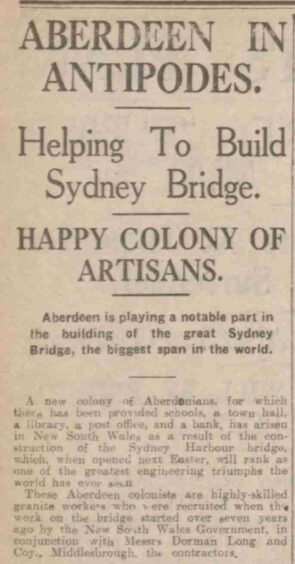

A ‘happy colony of artisans’

According to those that helped found Granite Town, the community was a happy one.

The P&J spoke to Mr Ennis during a visit home in 1931, a year before Sydney Harbour Bridge was officially opened, and he recounted stories of the ‘happy colony of artisans’ who made Granite Town into a “fair-sized village” with “scores of little Aberdonians… running about”.

Two of those ‘little Aberdonians’ were Sandy and Martha Campbell, whose father Alex brought his family to Granite Town in 1926 to work on the quarry.

Sandy, who was seven when he travelled to Australia, spent a chunk of his schooldays at Granite Town’s very own school while Martha, who was known as Mattie, was born in the settlement.

Tillydrone’s living link to Granite Town quarry

Sandy’s daughter, Norah Berry, who is 82 and lives in Tillydrone in Aberdeen, heard many of the family stories from her dad and auntie.

Like many descendants of the stonemasons, Norah remains proud of her family’s role in the building of the Sydney bridge though she’s never had a chance to see it herself.

In that, she is far from unique. Bill Glennie says many of the stonemasons didn’t see the bridge completed, either leaving Australia before it was opened or simply because they were based so far outside of Sydney.

There was a further irony in their long treks across the world to build a bridge they never laid eyes on. The granite pylons the stone from the Granite Town quarry was used for had no structural purpose.

They were entirely decorative, and so the bridge could incorporate memorials for soldiers killed in the Great War.

Still, their work lives on.

After the project was finished, Granite Town was transformed to Ghost Town, but Ennis, Gilmore and their fellow Scots had helped construct something special that would command headlines all over the globe.

Conversation