It’s quite something when the sweaters your company has designed and knitted are seen by 15.5 million people on prime-time TV on Christmas Day.

Especially when your company is a small enterprise based on a tiny island in Orkney, and started out making crochet Granny squares.

The Isle of Sanday Knitters (IOSK) must have felt they’d truly arrived when Neil Morrissey and Martin Clunes each wore a Christmas jumper specially designed and made for them by IOSK in the 1997 Christmas special of Men Behaving Badly.

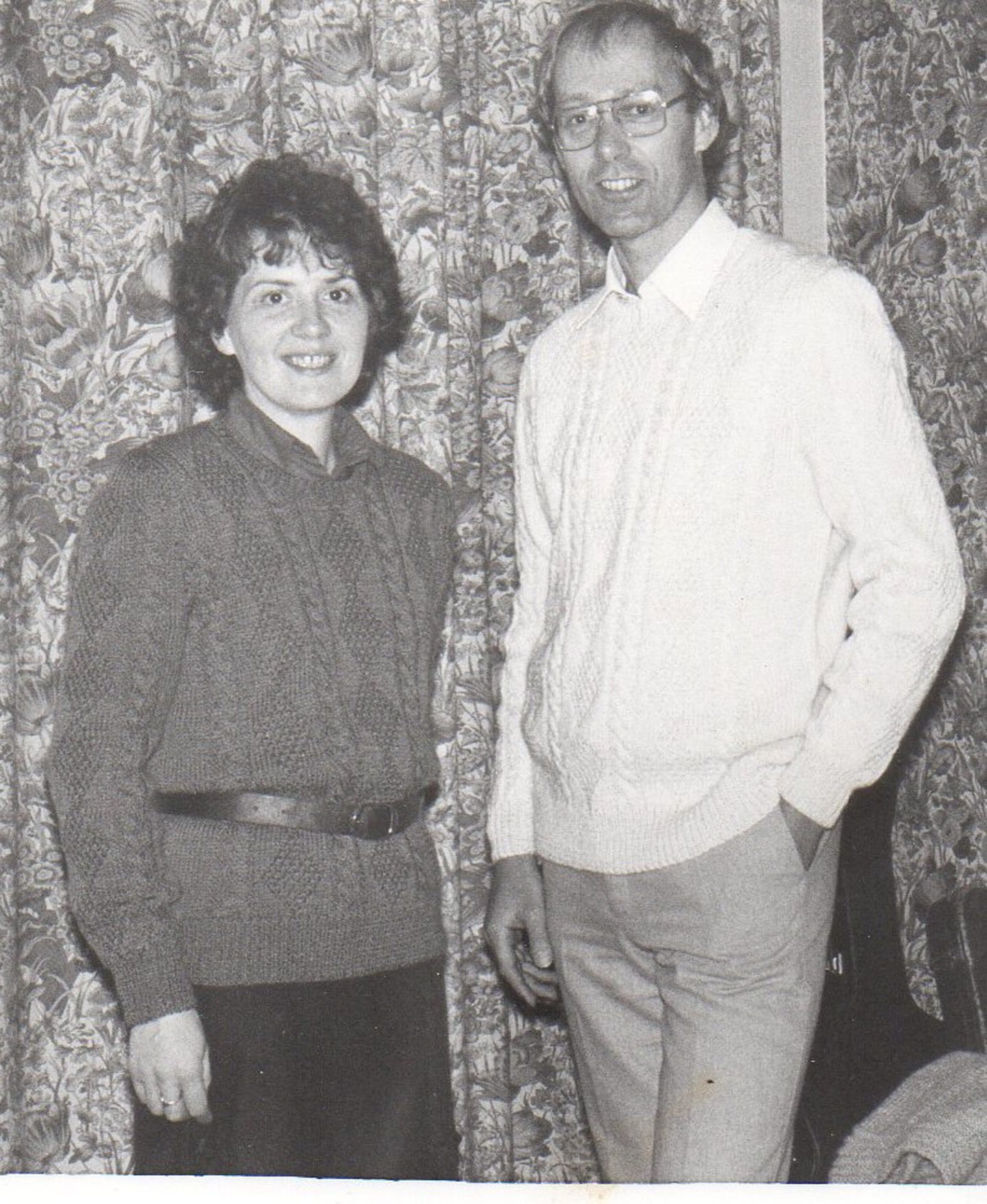

Sandra Towrie, IOSK’s main hand-knit designer at that point, made Neil Morrisey’s while her fellow knitter, the late Hilda Davis made ‘Doc Martin’s’ as she later called it.

Looking back these days, Sandra says she remembers having to churn the jumpers out at very short notice, and is relieved they were traditional style rather than the ‘lurid’ ones of today.

Sandra was practically born knitting

Originally from Shetland, Sandra had been knitting since she was knee-high, and could copy and/or design a pattern and then write it up in multiple sizes with ease.

At the time of the famous Christmas jumpers, she had spent more than 20 years with IOSK, and was then chairwoman of the board of directors.

During that time, several hundred knitters were involved, paid per garment, but it varied according to what else was going on on the island.

Sandra said: “It was difficult to maintain production in the spring and summer.

“Some knitters regularly produced six hand knitted sweaters a month for years, others only knitted if they wanted to buy something.

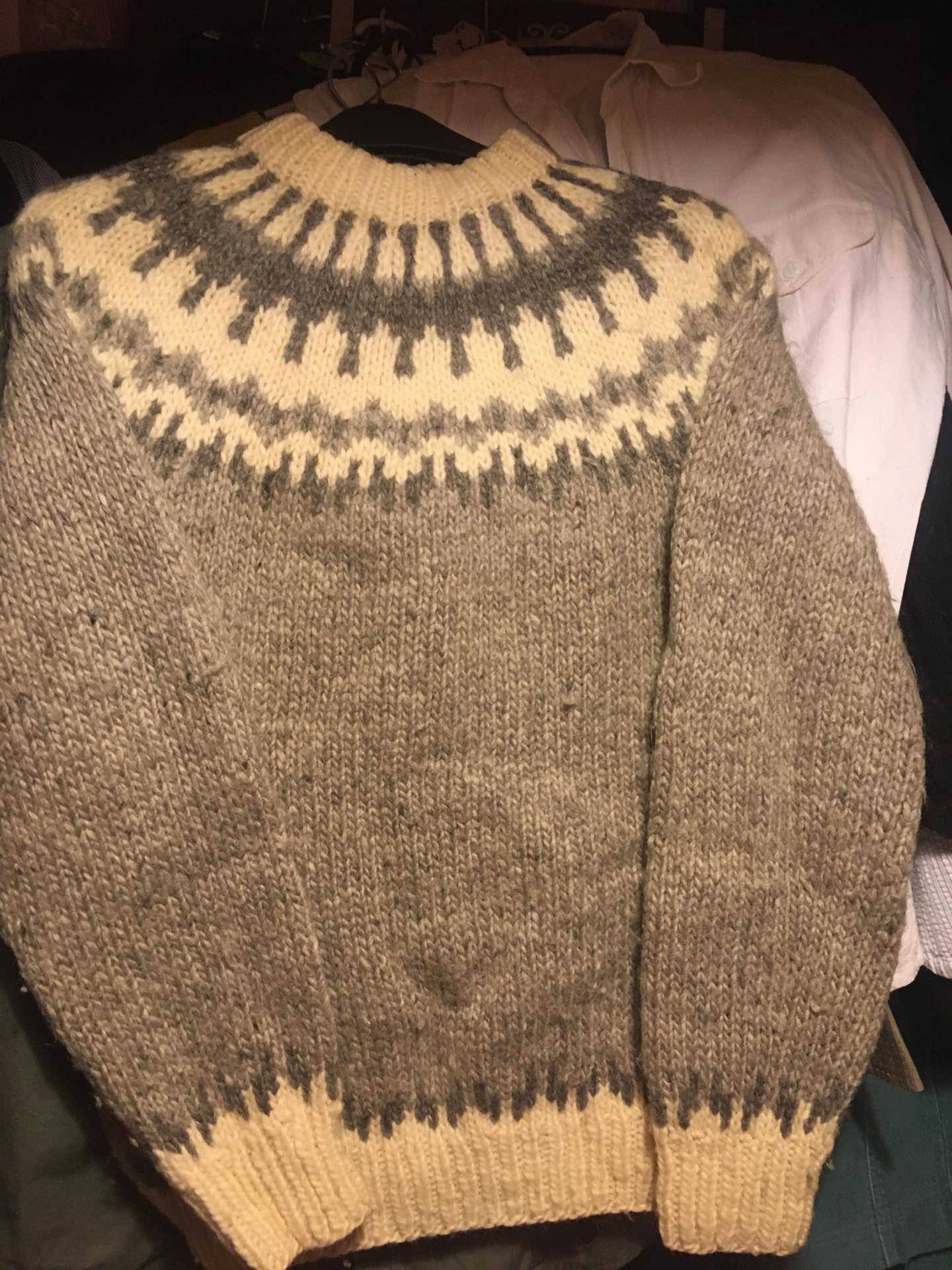

“Thousands of the more popular lines such as the Icelandic yoke and picture-front sweaters were knitted.”

Two years after its Christmas jumper triumph, IOSK was wound up amid rapidly changing times, and is now an almost forgotten slice of Sanday —and fashion—history.

Someone should write a book about this!

Realising that memories of IOSK were receding like the tide on the island’s shores, Sandra fell prey to the “someone should write a book about this” syndrome and then found herself to be that “someone” when she became custodian of the Isle of Sanday Knitters archive.

When funding came forward from the Northern Isles Landscape Partnership Scheme, Sandra had to get on with it.

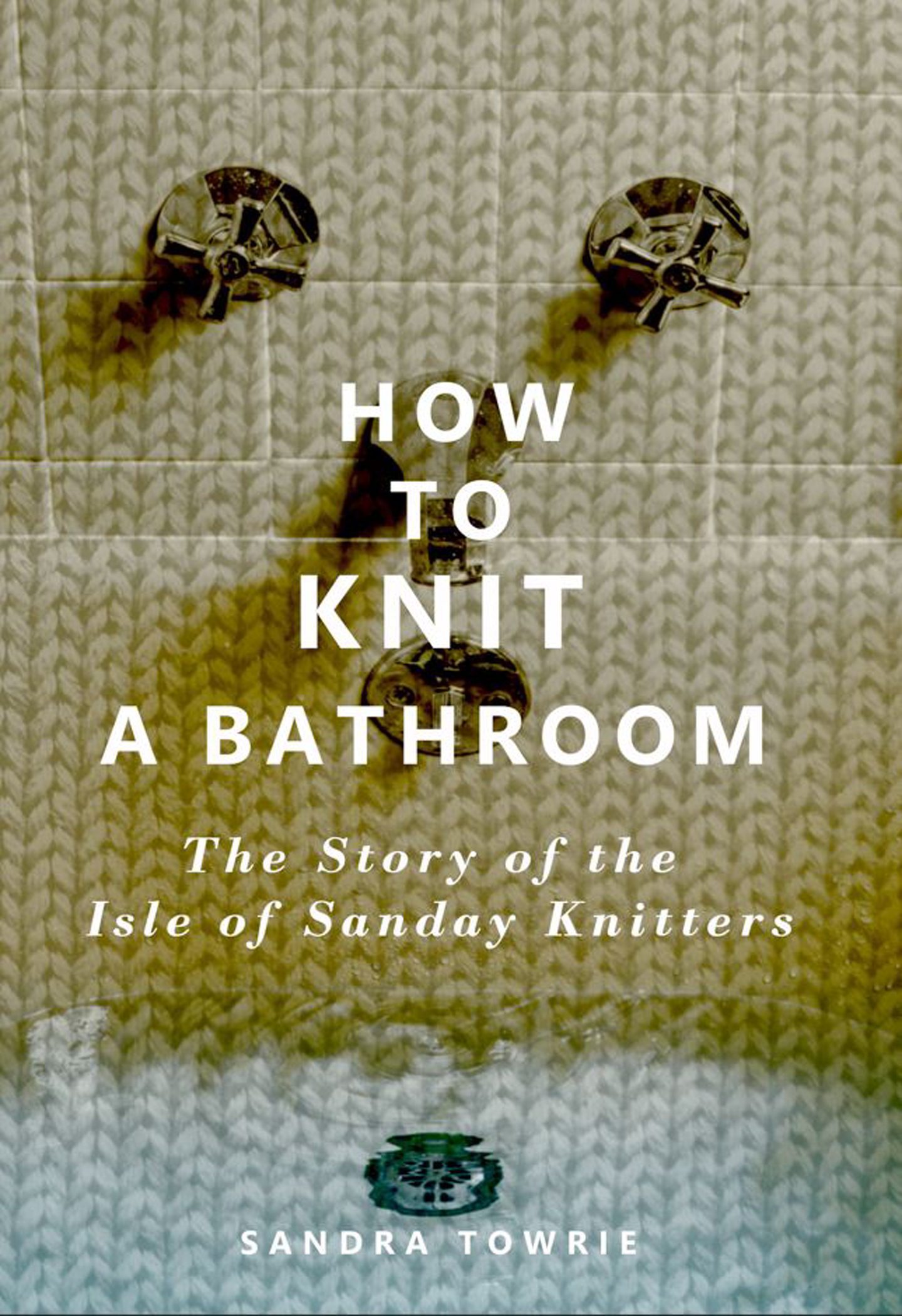

How to Knit a Bathroom is the result, a charming book describing a long-disappeared era in Sanday, when women could knit their way to that new bathroom, TV or holiday.

Sandra, now a retired teacher, said: “I got delved into all the boxes and got out the minute books.

“I talked to people of my age, in their 70s who can remember things and out it came.”

No mains electricity

It’s hard to credit how different life was in islands like Sanday in the ’70s.

Sandra said: “When I first came here as a newlywed from Shetland in 1972, we didn’t have mains electricity.

“You had to start the diesel generator to run your twin-tub washing machine or do a bit of hoovering, watch TV or anything like that.”

Women did hard unpaid work

Women were no strangers to hard, unpaid work around the farm and in the home.

There were few opportunities for paid employment, so in those days pin money might come from selling surplus cheese, butter and eggs from the farm.

But in the evenings it was the culture to sit down and knit for the family.

Women in the Northern Isles had knitting in their blood, and it was this culture that enabled IOSK to grow and thrive.

Two things happened to prompt the formation of IOSK.

A new teacher arrived, Ron Baker, with his wife Mary.

Although not a knitter herself, Mary would play a pivotal role in the development of the company.

The skill of the Sanday women didn’t go unnoticed

She noted how skilled the Sanday women were, knitting, crocheting, spinning wool, embroidering, making tapestries and sewing of all sorts, from the day-to-day necessity of patching overalls and darning socks to the highly-skilled fitting and tailoring of a dress for a dance or wedding.

Sandra says: “She also noticed how they uncomplainingly used their talents and abilities to contribute to the household economy without expecting any monetary gain for themselves.”

The next turning point came when Mary’s daughter came to visit in 1969, bringing with her a copy of Pins & Needles magazine.

Flicking through it, Mary noticed a company, Village Squares, advertising for outworkers to produce crochet squares for garments—very fashionable at the time.

Mary applied and got an order for 1400 squares, at 6d per square.

She recruited some two dozen knitters, the orders continued to flood in, the list of knitters grew, and eventually some 3,000 Granny squares as they were called, left the island for the world of fashion.

Some knitters earned the equivalent today of £75 or more.

Handiwork could become a source of income

Sandra says: “So the idea was born that the handiwork that was generally taken for granted could become a source of income.”

Once the Granny squares orders dried up, the women knitted a small collection of Norwegian inspired sweaters, and the redoubtable Mary Baker took them to show Sir Hugh Fraser of House of Fraser.

“She tipped the contents of a suitcase onto his desk and asked if he could sell such garments in his store. Presumably he liked what he saw because he placed a small order and the Sanday Knitters Association came into being. ”

Now the company started to be taken seriously.

With grant funding from the Highlands and Islands Development Board to become a co-operative in 1974, Isle of Sanday Knitters (Orkney) Ltd was born, with shares offered at £1 and a dividend promised at the end of the year.

There followed 25 whirlwind years as the company grew and grew.

IOSK got its own London agents, Wylie and Thorne and started knitting for designer Edy Lyngaas, not to mention an almost-contract for Alexander McQueen, the enfant terrible of the fashion scene in the late 90s.

Hitting the high-fashion scene —almost

McQueen had sent them instructions for a knitted denim dress which taxed even the most experienced knitters.

“It had to be knitted from denim dress fabric cut into strips 1-2cm wide, not a material which could be purchased from any yarn supplier,” Sandra says. “It had to be knitted on needles made out of dowling and had a tendency to fray.

“Some thought it might do to line a dog basket, others a doormat for inside the back door. ”

Despite their best efforts, the dress sank without trace once it made its way to McQueen.

Sandra spent the 1980s busy knitting, designing and excitingly, attending trade fairs all over the world until her youngest child went to school and she returned to teaching.

Her skill as a designer prompted HIDB to offer her a scholarship to study knitwear design at the RCA in London for a year, where her tutor, John Allen encouraged her to develop her own Sandra Towrie range for IOSK.

A pattern for Woman’s Weekly!

Then in a new pinnacle, Sandra was asked to designed a pattern for Woman’s Weekly magazine in 1994.

More than a thousand orders for the kits flooded in from around the world bringing in £7,000 profit for the company.

But all the while the world was changing.

By the early 1990s, more job opportunities were opening up for the island women, and fewer people on the islands were knitting, which meant orders had to be outsourced to other parts of the country.

“Our London agents were still securing orders, but it was becoming increasingly difficult to find enough knitters to complete them,” Sandra said.

“On at least one occasion we had to ask the customer to accept about half of the order because it was impossible to produce the remainder in time.

China became a serious competitor

“Alongside this, long-standing UK customers found they could source similar products more cheaply from China.”

Exchange rates were another potentially devastating variable, as was the crash in the Far East economy in the late 1990s.

There were no more grants to go to trade fairs.

Time to wind up

In 1999, the board of IOSK unanimously decided the time had come to wind up the company.

Sandra looks back on her time with IOSK with gratitude.

She said: “I was a teacher, and in those days you had to resign when you became pregnant.

“I didn’t enjoy the baby years very much and being stuck at home, I was bored out of my skull.

“It was a way to earn money, to take up my time, and an opportunity to travel to trade fairs.

IOSK broadened Sandra’s outlook

“This broadened my outlook and prepared me for the time when I would volunteer in Africa, delivering in-service training courses to up to 150 teachers.”

And yes, Sandra’s still knitting. She’s currently turning some beautiful vintage yarn she found at her mother’s in Shetland into an all-over Fair Isle cardigan, and she could probably do it in her sleep.

How to Knit a Bathroom is available from Orcadian Bookshop, and can be ordered www.sandaydt.org/book £9.50 plus £2 p&p

All proceeds from the book will go to Sanday Heritage Centre, part of Sanday Development Trust.

Conversation