Among Aberdeen’s architectural giants like Marischal College and King’s College, it’s easy to overlook the city’s understated Art Deco buildings.

Looking beyond Aberdeen’s grey reputation, it’s home to incredibly rich and diverse architecture.

Over many centuries, the coarse granite on which it is built – and built from – has been honed and skilfully crafted to create beautiful landmark buildings.

Aberdeen’s whole identity has been carved from granite.

Subtle Art Deco gems stand out from showy Victorian architecture

Whether that’s the ancient St Machar’s Cathedral to, by comparison, more modern masterpieces like the trio of civic buildings – the Central Library, St Mark’s Church and His Majesty’s Theatre – on Rosemount Viaduct.

But away from the showy 19th Century Gothic Revival buildings, Aberdeen is home to some hidden – and not so hidden – gems of the Art Deco era.

Its subtle Art Deco buildings have survived remarkably well, considering not all were built in hardy granite.

Art Deco was an art, interior and architectural movement borne from Paris before the First World War.

But it only really gathered pace after the brutality of the conflict amid an appetite for change.

Aberdeen led the way in progressive town planning during the 1930s

Art Deco represented a departure from the romance and fussy flourishes of the Victorian era – it was futurist, clean and modern.

But it wasn’t until the 1925 Paris exhibition, Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, or Art Deco for short, that the movement gained its name.

Art Deco was quickly adopted, with function becoming as important as form in global architecture during the inter-war period.

The hallmarks of this architecture, conceived during a time of optimism, is still evident in Aberdeen’s surviving Art Deco buildings.

During the 1930s, Aberdeen was a progressive city and led the way in Scotland in terms of forward-thinking town planning with a capable team of architects at the helm.

Ahead of a global celebration of Art Deco taking place in 2025 to mark the centenary of the movement, we’ve taken a look at groundbreaking Art Deco Aberdeen.

1. The Regent Picture House, Justice Mill Lane, 1932

Architect: T Scott Sutherland

Art Deco and cinemas went hand-in-hand, and incredibly three of Aberdeen’s Art Deco cinemas still survive, albeit under new guises.

Designed by renowned Aberdeen architect T Scott Sutherland – who specialised in cinema design – the unusual Art Deco meets Baroque style Regent stood out for its “dignity and beauty”.

Built on the sloping sight of the former Justice Mill, it cost £32,000 alone to excavate the site.

Upon its opening, the Evening Express said: “Even though Aberdeen has many magnificent edifices, there is nothing quite so distinctive as the modern design of the front of the new Regent.”

It was bought by the larger Odeon chain in 1940 and remained a cinema until June 2001 when it was turned into a gym and health club.

2. Jackson’s Garage, 10-12 Bon Accord Street, 1937

Architect: AGR Mackenzie

Just a stone’s throw from Union Street, this incredible building is an Art Deco rarity – it’s an uncommon, surviving example of a commercial Art Deco garage.

Jackson’s Garage gently follows the curve of Langstane Place turning into Bon Accord Street leading to the striking main facade.

The facade itself perfectly embodies Art Deco with its slender Crittall windows, stylised clock, a bronze torch and rooftop lantern mast.

It originally housed showrooms at the front with office space at the back, and had a ramp leading to a car park on the roof.

The building has long been occupied by Slaters menswear upstairs, and downstairs has recently been turned into Monty’s Wine Shop and Bar after previous shop Oddbins closed.

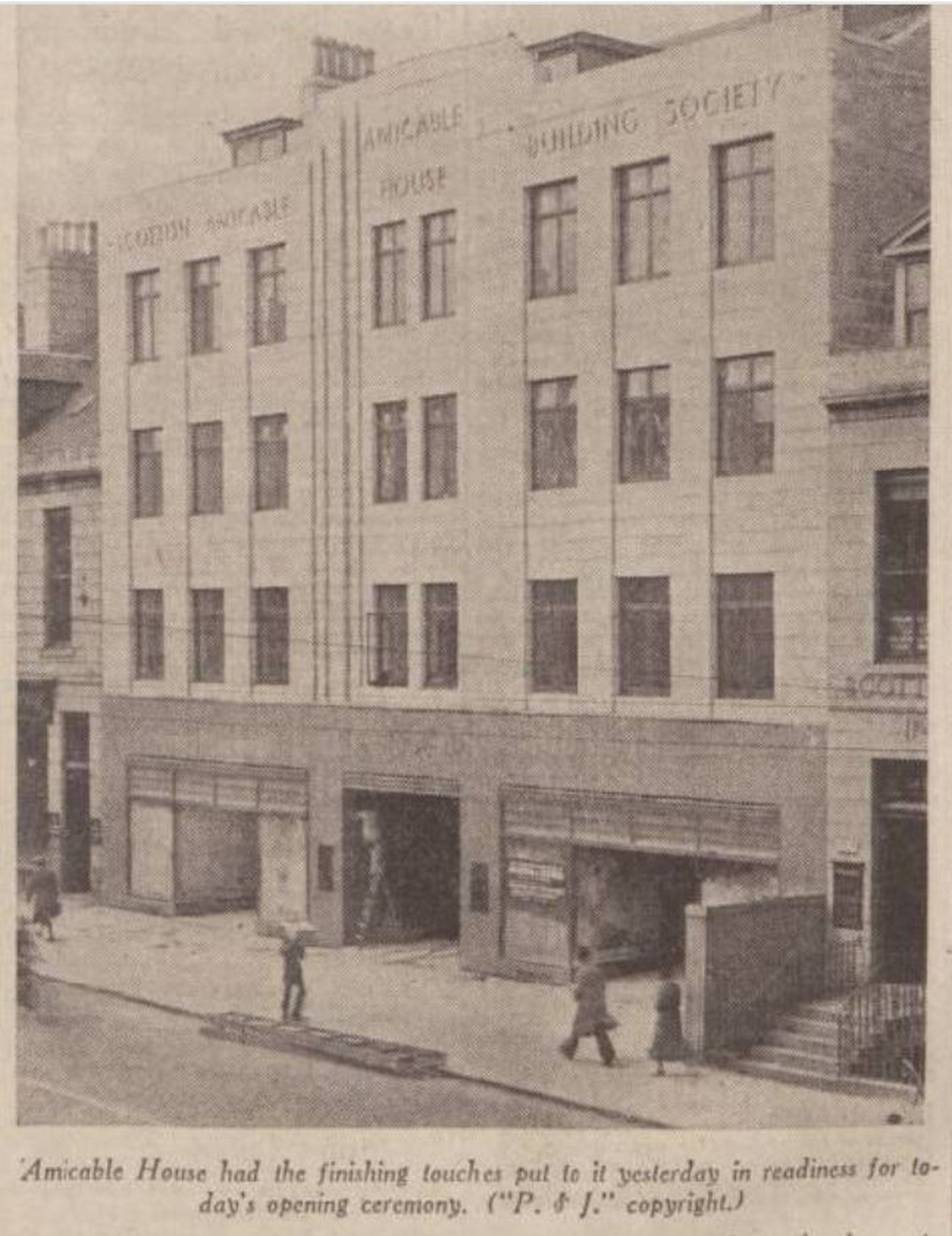

3. Amicable House, 250-252 Union Street, 1935

Architect: T Scott Sutherland

Built from Kemnay granite, Amicable House opened as a “handsome new business centre” on Union Street in 1935.

It was designed for the Scottish Amicable Building Society in 1934 and features classic Art Deco architecture displaying the ‘rule of three’ in its window placement.

Upon its opening, the P&J reported said the way in which Amicable House “combined beauty and business efficiency” set an example to other cities.

Described as “an achievement worthy of the city at its best”, the ground floor featured bronze shop fronts while the main entrance to Amicable House had a marble and terrazzo floor with bronze entrance doors.

The building had two floors of spacious office suites with wood panelling, and two two-bedroom flats were incorporated into the roof space complete with a roof garden.

Amicable House has always been in use as offices and in December 2024 went on the market for £750,000.

4. The Capitol, 431 Union Street, 1933

Architects: Clement George and Marshall Mackenzie

The Capitol was built on the site of Aberdeen’s first-ever cinema, the Electric Cinema.

When the Art Deco replacement opened in 1933 it was described as “a triumph of artistry”, designed to “please the eye and charm the ear”.

Aberdeen’s latest entertainment venue was pure luxury, furnished with terrazzo flooring and walnut panelling, offering guests a sophisticated restaurant with views over Union Street.

The main auditorium had sweeping Art Deco curved lines, delicate plasterwork and the jewel in the crown – a state-of-the-art Compton theatre organ which could be raised and lowered into the orchestra pit below.

When the golden age of cinema was over the Capitol became a live music venue in the 1960s, hosting stars like The Rolling Stones, Queen and Johnny Cash.

It closed suddenly in 1997 until it was turned into Jumpin’ Jaks nightclub in the 2000s.

The nightclub closed in 2009 and the whole site was regenerated and opened as an office space in 2016 incorporating the restored B-listed Art Deco facade.

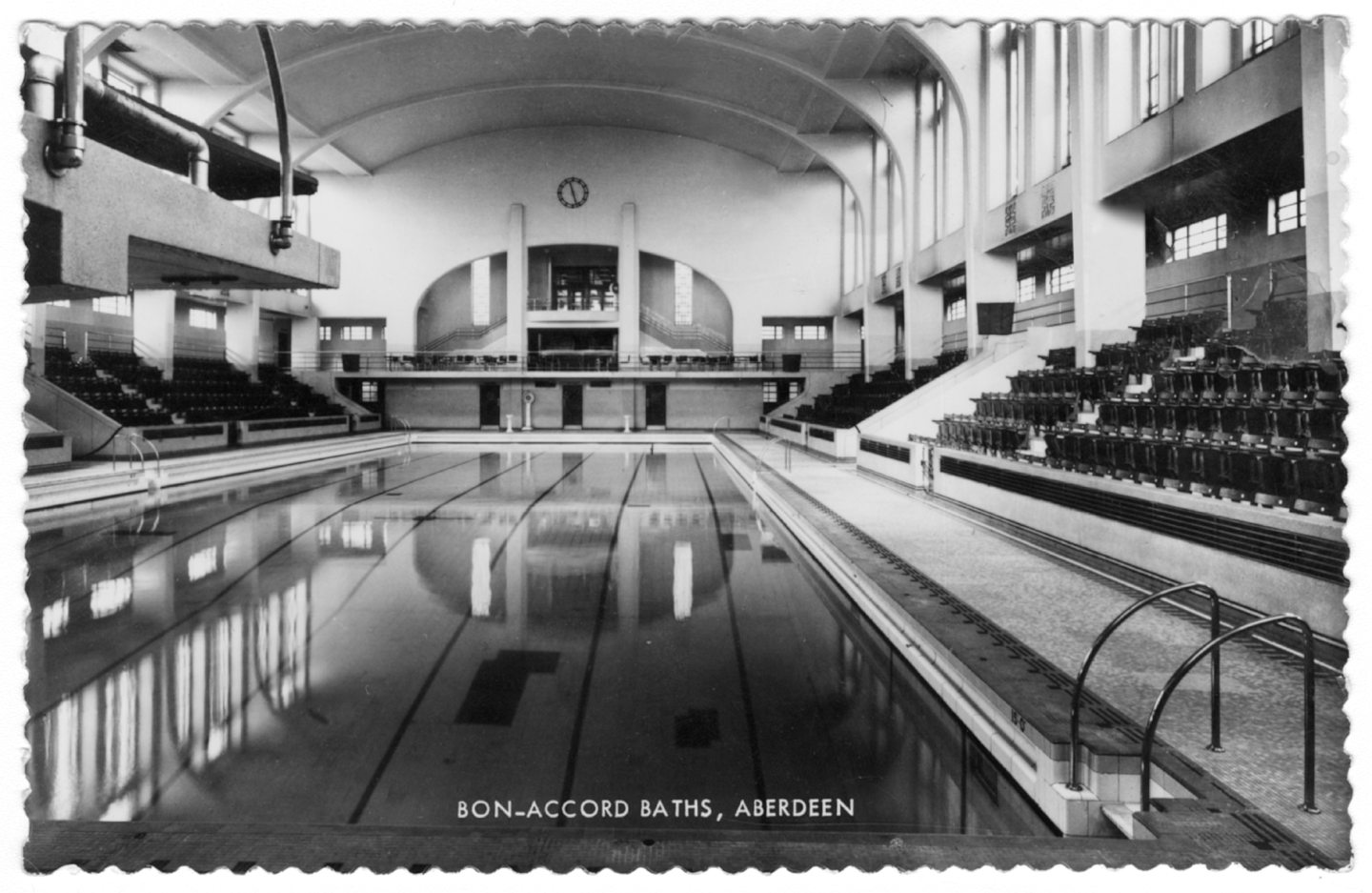

5. Bon Accord Baths, Justice Mill Lane, 1940

Architect: Alexander McRobbie

Aberdeen’s famous Bon Accord Baths is a very rare surviving Art Deco swimming pool with an elegant reception featuring sycamore panelling.

The corporation baths were built at a cost of £103,000 and the opening ceremony on August 30 1940 was attended by 800 people.

Construction was delayed by war, but when it opened, Councillor James Hay said he had seen many public baths across the country and “not one was superior to it in equipment or in beauty”.

Typical of the Art Deco style, the majestic pool has a vaulted, curved roof and delightful symmetry, while large windows flood the building with light.

The pool also played an important role in public health as many overcrowded tenements still shared bathrooms.

Bon Accord Baths closed in 2008, and it fell into disrepair, but now Bon Accord Heritage is working towards restoring the precious building to bring it back for community use.

6. Douglas Hotel, Market Street, 1937

Architect: A Marshall Mackenzie

A city landmark, the Douglas Hotel is one of Aberdeen’s oldest hotels and to this day it retains its distinctly Art Deco appearance.

But it was a much earlier Victorian building dating to 1848, remodelled and ‘modernised’ in the Art Deco style in 1937 at the cost of £40,000.

It was a huge project which extended the hotel upwards from a 46-room premises to 112, along with the addition of a new dining room, cocktail and buffet bars and a ballroom twice the size of its predecessor.

The new dining room featured oak panelling, sumptuous carpets, a large fireplace with a large mural depicting Mary Queen of Scots’ entry into Aberdeen.

While the P&J said Aberdeen’s young people “will find it a sheer joy” to get their feet on its oak-floored ballroom.

Outside, an Art Deco copper canopy and recessed copper panels were added and although the canopy was later removed in 1948, it was restored to its former glory in 2012.

7. Montague Burton Building, 73-79 Union Street, 1932

Architect: Harry Wilson

Montague Burton, the tailor, built Art Deco shops up and down in the country between the 1920s and 1950s.

One such premises is the striking building on the corner of Union Street and Market Street in the heart of Aberdeen.

Often Monty’s own children laid the foundation stones. If you look closely at the former Aberdeen shop you’ll spot a little plaque which reads “his stone laid by Stanley Howard Burton 1932” – Monty’s son.

Burton particularly favoured corner sites and the buildings’ trademark was often a polished black granite facade.

Burton operated in the building until around 1980 and it was later occupied by Topshop.

Now empty, the C-listed building is looking a little worse for wear, but externally it retains glorious original Art Deco features and windows.

8. Rosemount Square, 1945-46

Architect: Leo Durnin

The colossal Rosemount Square was a social experiment, built in response to a dire need for more housing in Aberdeen.

Designed in 1938, it was delayed by the war. It was the last tenement block built in the city at a time when the modern principles of Art Deco aligned with a desire to build a better society.

Rosemount Square is a unique structure – heavily influenced by socialist ideology and executed in granite – there is no other building like it.

An innovative take on the traditional tenement, it takes a horseshoe form with a central courtyard.

The curved granite bulwark on the outside features carved reliefs depicting rain and wind, designed by then head of sculpture at Gray’s School of Art, Thomas Huxley-Jones.

The tremendous tenements were given category A-listed status in 1987 recognising the building’s national significance.

9. The Northern Hotel, 1 Great Northern Road, 1942

Architect: AGR Mackenzie

When the Northern Hotel opened in 1942 it was described as “the most fashionable in the north-east of Scotland”.

It replaced an earlier Victorian hotel which was destroyed by fire and was built in the ‘continental style’.

The Northern Hotel epitomised the Art Deco movement. With its curved facade and rows of Crittall windows, it looked like an ocean liner pushing through the Victorian housing of Kittybrewster.

Completed in the early years of the war, the hotel was fully open by 1942.

It was a popular spot for decades, although many of its interior Art Deco features were lost during subsequent redevelopments.

A planning application was submitted in April 2024 to turn the hotel into student halls, which has now been approved.

10. King’s Pavilion, University of Aberdeen, 1941

Architect: A Marshall Mackenzie

The B-listed two-storey sports pavilion was built for King’s College University Athletic Club in 1941.

The Art Deco concrete and glass facade contrasts sharply with surrounding historic buildings, but was said to have “an air of lightness and gaeity”.

An outstanding feature of the pavilion is its wraparound balcony, and inside, the swimming pool and plunge bath in the centre of the ground floor.

On the upper floor, a tearoom overlooked the sports ground on one side, and on the other, the swimming pool balcony.

Historic Environment Scotland describes it as “a rare and largely-unaltered example of a Modern sports pavilion”, which “adheres to the Modern movement principle of ‘form follows function'”.

The pool fell out of use when nearby Aberdeen Sports Village opened, but the pavilion is still used as a gym and performance venue.

11. Aberdeen Beach Ballroom, 1929

Architect: Thomas Roberts & Hume

The ballroom is perhaps Aberdeen’s best-known Art Deco building, perched at the end of the boulevard overlooking the steely North Sea.

It was built at a time when Aberdeen Town Council was riding the crest of a wave of public-spirited improvements.

Regarded as a rare survivor of the era, elements of the ballroom are very typical of the Deco style.

But it’s regarded as more unusual due to its octagonal shape and pyramidal roof, which is set back from the wings and main entrance.

The B-listed landmark continues to be used as an entertainment venue, happily fulfilling its original purpose.

12. Tullos School, Girdleness Road, 1937

Architect: J Ogg Allan

Built to serve new housing estates nearby, Tullos Primary School is an exceptional example of Art Deco architecture in municipal buildings.

Solidly built in granite, Tullos School takes the form of a low two-storey block with curved ends, while a distinctive glass stair tower stands in the middle.

The school was first proposed in 1937, with work beginning shortly after.

But the onset of war delayed its completion until 1950, although around 400 children had been attending since August 1949.

The official opening on April 27 1951 was the last civic duty of Lord Provost Duncan Fraser, who said: “This is undoubtedly one of the finest primary schools in the country.”

Now B-listed, the building is still very much in use as a school at the heart of the community it was built to serve.

More Past Times stories

10 lost streets of Aberdeen brought back to life in technicolour

A history of the Marcliffe in pictures: From Tivoli Theatre boarding house to luxury hotel

Unseen photos of Aberdeen’s trams revealed in nostalgic new book

Conversation