No match fees or bonuses, no sponsorship deals or even the chance to write your autobiography… such was the reality of amateur rugby a century ago.

Indeed, when Scotland’s Jimmie Ireland swapped shirts with Sam Tucker, the England hooker, after his side had beaten the Auld Enemy at Twickenham, he was sent a bill of 12 shillings and sixpence (around 62p) by the SRU for losing his jersey.

The rules were carved in stone and players were expected to obey them or else, even though this was a halcyon period for the Scots, which produced a piece of history.

It’s a century this year since they surged to their first-ever Grand Slam at the newly-opened Murrayfield Stadium with a brio and bonnie belligerence.

On his way to one of the matches, Gaelic-speaking Highland stalwart John Bannerman even asked a couple of mates on the train to Edinburgh: “Who are we playing today?”

Yet, once the contest started, this resilient fellow was always in the thick of the action.

He later skippered his country with distinction. But it was another Highlander – George Philip Stewart Macpherson from Newtonmore – who led his compatriots to something unprecedented, though you would hardly guess it from the lack of media coverage.

It wasn’t called the Grand Slam in these days. That was a bit populist, a tad too gimmicky for the Twickers set and the Murrayfield panjandrums.

No names and certainly no pack drill

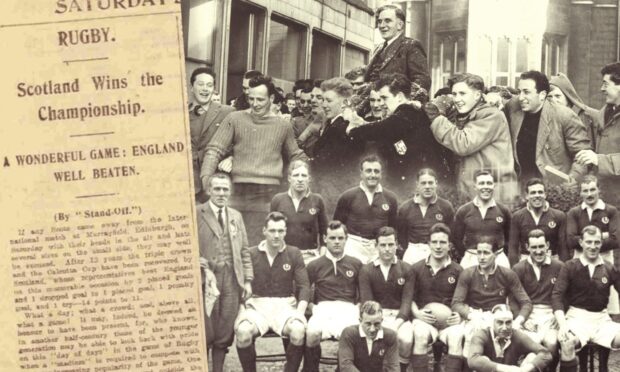

And many newspapers, including the Press and Journal, carried reports from anonymous correspondents, without any pictures to indicate something momentous had happened.

Thus it transpired that “Stand-Off” heralded the narrow victory over England in March 100 years ago to complete a campaign which had commenced in January 1925.

The Scots had already defeated France 25-4, Wales (in Cardiff) 24-14 and Ireland (in Dublin) 14-8 and had served up a potent blend of power and panache.

So there was plenty of anticipation in the build-up to the showdown with the English, which turned into a battle of attrition, occasional artistry, and fluctuating fortunes.

Scotland deserved their victory

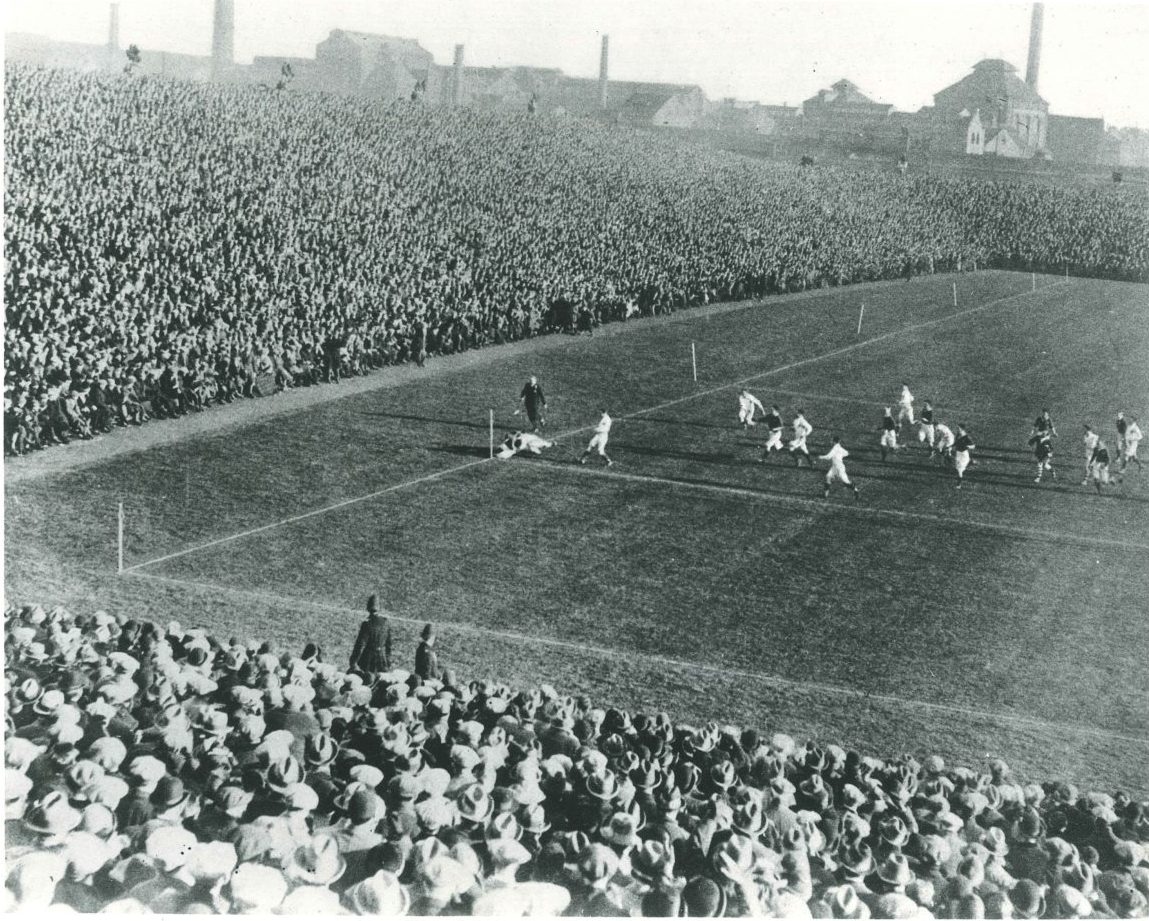

England scored first, in front of the 70,000-string crowd, with a penalty goal, but the hosts quickly reversed things with a converted try which made it 5-3.

However, a brace of English touchdowns followed, one of them converted, to put the visitors in the ascendancy once more by 5-11 and leave the outcome finely balanced.

With 25 minutes remaining, Scotland scored again, but the try proved controversial, with the English claiming a foot had been put into touch before the ball was grounded.

However, the Welsh referee Mr Freethy was unconvinced by these arguments and it was duly converted, taking the Scots to within two points of victory: 10-11.

It was a nerve-shredding finale

Even as the spectators grew increasingly vociferous, Macpherson’s men piled on the pressure in a desperate attempt to seize another try, but fell agonisingly short.

And then, with just five minutes to go, the Scottish fly half, Herbert Waddell, slotted a drop goal, taking the score to 14-11 and securing the Grand Slam. And bedlam erupted.

The P&J’s verdict hardly suggested the tussle had gone right down to the wire. On the Monday afterwards, it delivered its verdict: “England Well Beaten”.

And that summed up the mood at a time when the likes of Bannerman and Macpherson had to fit in their rugby assignments alongside their day-to-day careers.

Training sessions were for the future

Matters hadn’t changed much 59 years later when the Scots gained their next Grand Slam success and scrum-half legend and electrician by trade Roy Laidlaw found himself rewiring the public toilets in Jedburgh less than 48 hours after besting the French.

But at least by then, the players were coached, enjoyed pre-match training sessions, devised strategies to outwit their opponents and were moving towards professionalism.

None of that should detract from the heroics of the Class of ’25, nor diminish the qualities of their lustrous personnel, including the formidable Bannerman.

After all, he participated in 37 consecutive matches, all but one of them in the Five Nations Championships, between 1921 and 1929.

Stepping gaily, on they marched

And, more remarkably, he celebrated no less than four victories over the English, the last of them as captain; a result which this patriotic figure, whose father from South Uist wrote the famous song Mairi’s Wedding, savoured with a dram and a song.

The redoubtable lock forward was imperious in leading from the front and, according to his grandson, Shade Munro, another ex-internationalist, he genuinely bristled with purpose and commitment whenever he pulled on his country’s jersey.

He said: “I have a picture of him skippering the Scots to victory at Murrayfield and the pride in his eyes is absolutely immense.

The Gaels worked themselves up

“In these days, the Five Nations journeys down to England were grand occasions, and although my grandad always offered 100% in his nation’s cause, he would prepare even harder for the Calcutta Cup matches against England.

“There were quite a few Gaelic speakers in the side at that time and they didn’t half work themselves up for these contests. But it definitely paid off with four victories in five years [from 1925 to 1929] being a pretty amazing record.”

(Incidentally, the 1930 match finished as a 0-0 draw; a truly pointless exercise).

The players of that vintage had none of the profiles of the current Scotland team, nor, one suspects, would many of them have desired appearing in banner headlines.

But Bannerman was somebody who made his mark on the world, on and off the field.

He was a Mod hit in the 20s

In 1922, he won the prestigious gold medal for solo singing at the Royal National Mod in Fort William. And he was president of An Comunn Gàidhealach, the national Gaelic Society, a position previously held by his father, John, from 1949 to 1954.

Then, there was his elevation to the rectorship at Aberdeen University where he told the students about the importance of adapting to a changing world and being ready for it.

He was also chairman of the Scottish Liberal Party from 1954 to 1964 and became Baron Bannerman of Kildonan in 1967, just two years before his death.

But he was prescient about what he perceived as a new trend in Scottish politics; the rise in support for the Scottish National Party.

They will keep gaining votes

During his maiden speech in the Lords, Bannerman spoke passionately about the anger of voters in Hamilton, where the SNP had just won a parliamentary by-election.

And he warned this reflected the anger of two centuries in which the Scots had been a “sleeping partner” in the UK political scene, a situation which be argued had to change.

Bannerman succumbed to lung cancer in 1969, but he was passionate about his Gaelic roots and spoke about the benefit of sport all his life.

He might have occasionally wondered which team he was playing against. And yet everything he did in a blue jersey demonstrated his passion for Scotland.

The Highland influence was strong

It would be nice to imagine there will be more north men in his mould orchestrating triumphs in the future. Players from South Uist rather than South Africa.

But we had better not hold our breath on that score!

Conversation