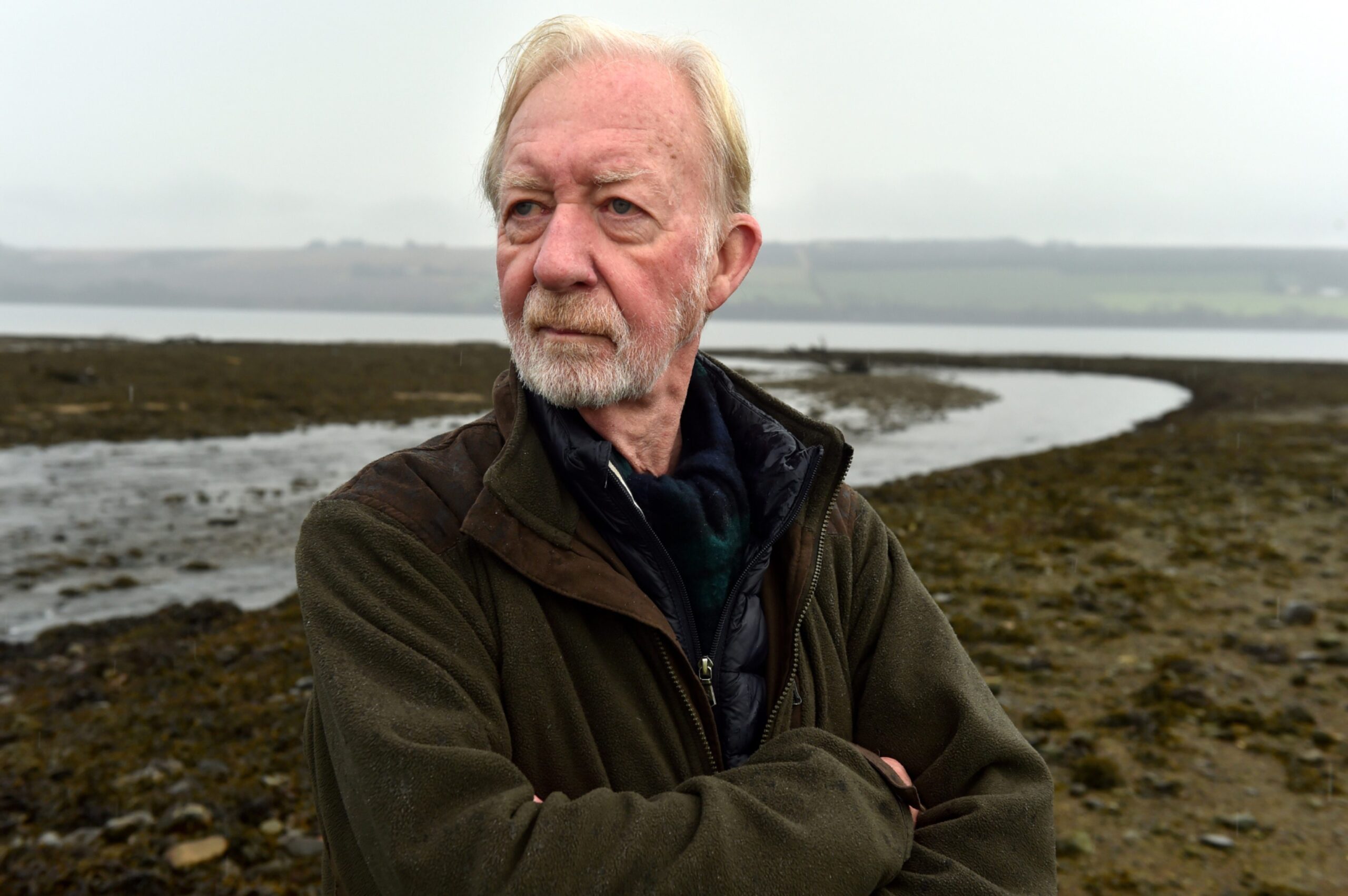

George Chamier’s knowledge of the Cromarty Firth and its finest fish, Salmo Salar, the wild Atlantic salmon, knows no bounds. And his love for both is nothing short of a passion.

He’s one of a dwindling number of fishermen and women who still know how to catch salmon with net and coble.

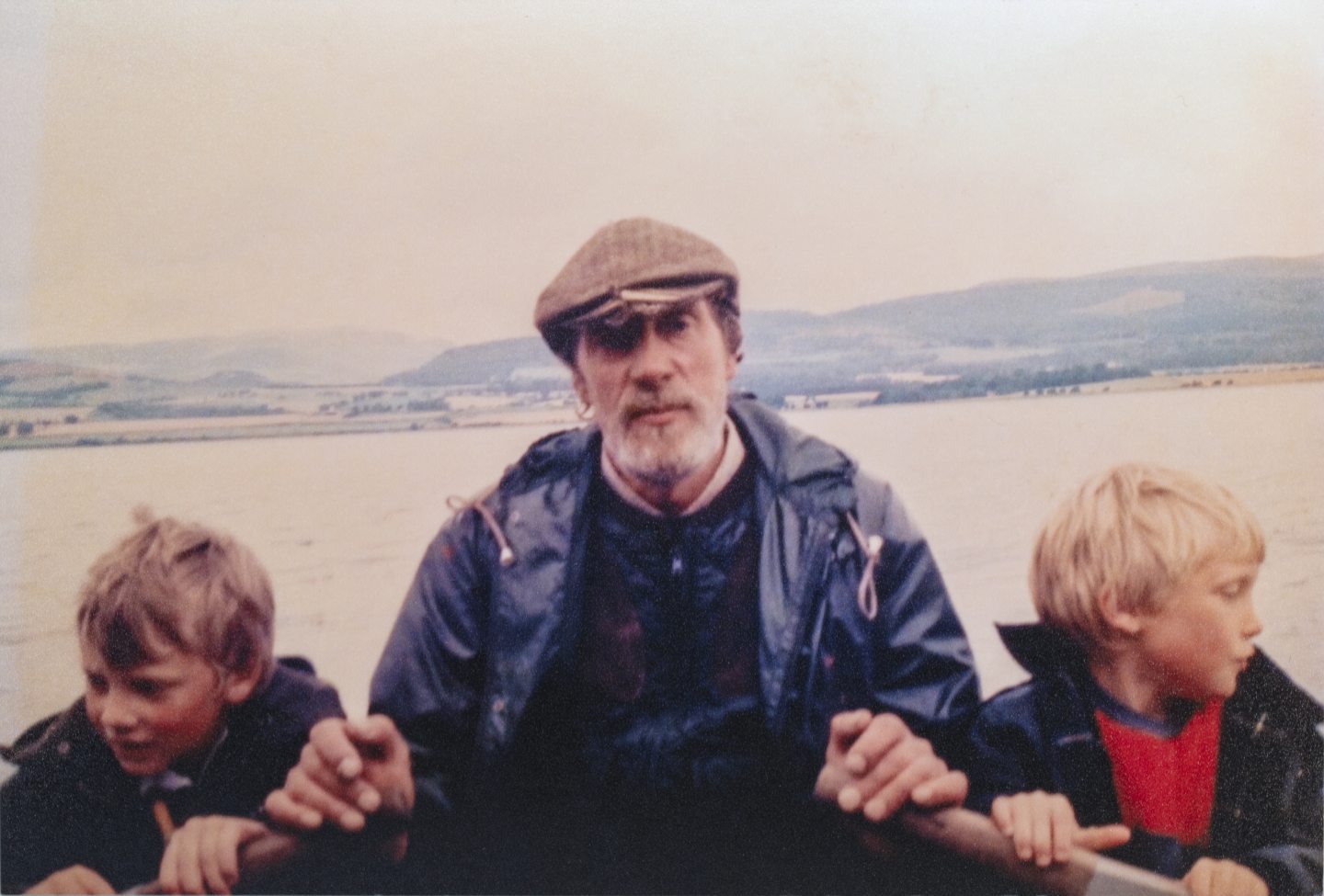

A coble is a small fishing boat which rows out when salmon are spotted migrating up the river from the sea and deploys a net to encircle and trap them.

George started on his fishing journey as a schoolboy in the Sixties and worked with a cast of legendary characters at different times on the Cromarty Firth until 2018, when it was declared a mandatory catch and release zone.

To begin at the end of his story (which he’s captured beautifully in his memoir, With Net and Coble, A Salmon Fisher on the Cromarty Firth, Pen and Sword History 2021) George shares his nostalgia and sadness for those long-gone days.

“First and foremost, the fate of Salmo Salar himself.

Once the firth was full of salmon

“When I think of the firth full of silver fish, as it was every summer, and as we just expected it would always be, it’s pretty hard to contemplate what has happened to him — overfishing at sea, pollution, aquaculture with thousands of farmed fish escaping and interbreeding with the wild population, and the ongoing effects of climate change.”

Then there was the loss of the social side.

“I miss watching water, one of the joys of the way we fished, and healing to the spirit. I miss the camaraderie of the fishing – there’s nothing like spending hours on the water for getting to know your fellow man, and occasionally woman.

“Then there’s lost youth, of course, and the carefree-ness that went with it.”

But before reaching this point of regret and nostalgia, George packed in a memorable half century communing with the Firth, its fishers and fish.

George’s mother was from the area

His mother’s family, the Munros of Foulis, belong to the area.

George said: “She was brought up in Perthshire and England, but spent time with her grandparents in Ross-shire. I have known the area all my life – my childhood was largely spent abroad as my father was then in the army, but my parents had a house in Easter Ross, near Kildary, and we spent holidays there.

“When my father retired from the army and became estate factor for Novar Estate, we moved permanently to Ross-shire.

“I was then about 11. I was at boarding school in England, but spent all holidays and from university, as much time as possible in the north.”

Fishing was a holiday job, but one which George found he loved.

It remained a holiday job for many years.

Schooled at Eton and Cambridge

George went to school at Eton, and read law at Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

But law had no appeal to the young George, and he got a job working for an advertising agency in London for the next six years, followed by a stint in Amsterdam.

It turned out this didn’t suit George any better than law.

“I didn’t like it really, the crass commercialism, telling lies to sell things to people, all of that.

“So I dropped out.”

Returning to the Cromarty Firth

By way of solace, George turned to the salmon fishing.

“I came back here, and it was a happy accident really, the fishing here at Balconie Point was available, so it all meshed together and became 12 years full-time fishing.”

The work only lasted for five months of the year, so depending on how good the season had been, George either didn’t do very much for the rest of the year, or picked up outdoor work locally.

He didn’t leave for 12 years.

They fished from Balconie Point on the shores of the Firth just north of Storehouse of Foulis.

It was here in 1967 that George first met James Black, aka Buller, one of the great characters who enriched his fishing life and became his fishing ‘guru’.

George said: “Buller fitted his rounded, broad shoulders and his full ruddy cheeks.

“By God he knew the fishing —not just the practical matters of care for boat and net or the tactics of where to fish in any given combination of wind and tide, but the essence of it.

“His patience was inexhaustible, he could spot fish anywhere and when they did appear he reacted with speed and decision.

“It was as if he could smell them.”

Not all the fish found their way to the laird

At this point, George’s father, aka The Brigadier, was factor to the estate, potentially awkward for the fishing crew, who had their own way of calculating their rewards.

Let’s just say not all the fish caught, technically the property of the laird, found their way to the market.

George said: “The first few times I saw Buller slip a fish to one of the crew he muttered some apologetic remark, but pretty soon he saw that I wasn’t going to blab, and in any case I got to take the odd fish home for myself.”

Doug was another character much loved by George.

“I have never met anyone like him” he says.

“We were known as the Balconie Babes at that point and were psuedo-hippies in those days, strictly green tea, weed and macrobiotic food, and Doug, a bit older with his tattoos, gappy teeth and cans of Special Brew, came as a bit of a shock.

“But it soon became clear that despite the rough exterior and the extraordinary accent, equal parts The Broch, Lancashire and Essex, he was really a great big huggy bear.

Adrift in the Caribbean with a crate of Guinness and a packet of cocktail pork sausages

“Doug could turn his hands to most things in the building line and he had a remarkable backstory, episodes from which emerged during the long hours in the boat at Kiltearn when not much else was happening.

“He’d say, ‘did I tell you about when I played drums with Lonnie Donegan?’ Or, ‘did I tell you about the time I was cast adrift in the Caribbean with a crate of Guinness and a packet of cocktail pork sausages?’

“When the fishing was slow, he would say, ‘It’ll never catch on as a spectator sport’.”

Spending so much time in a boat or watching from the shore meant the fishermen became accepted by fellow fishers, the kind with wings.

Sightings of osprey, cormorants, terns, curlews, greater black-back gulls, geese, ducks, buzzards and peregrine were all in a day’s work for George.

But the wildlife too has changed over the decades.

“You don’t see any shelduck now,” he says. “But on the other hand broods of eider ducks have become a familiar sight.”

The fishermen called the many common seals they came across ‘Henry’.

George said: “Seals are known to like music so one day we took a piper of our acquaintance out to play to them. They showed a lot of interest.

“Our relationship with Henry is a complicated one. Often we curse him, when we see what looks like a big shot of fish coming towards us, only for the shiny black seal head to pop up instead.”

‘Fishing was the best job I ever had’

After he left the full-time fishing, George went to the University of Lancaster to do a history degree.

He became a history teacher, but returned in the holidays to fish.

“My time full-time fishing was the best job I ever had and the bit I enjoyed the most,” he said.

“It was a way of life, and probably gone for good now, unless salmon stocks recover, but it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen, not in the near future anyway.”

Conversation