Portlethen was once one of a string of traditional fishing villages sitting atop the cliffs of the Kincardineshire coast.

Its name derived from the depths of the sea – Portlethen was originally said to be Port Leviathan named after whales that came ashore there.

And in the late 20th Century, the community certainly grew to whale-like proportions.

In the 1961 census, the population of the entire district was around 460 — 236 in Portlethen (Station), 75 in Old Porthlethen, 77 in Findon to the north and 69 in Downies to the south.

The population of the district is now estimated to be around 8969 – and growing.

Old Portlethen was enveloped by development in 1970s

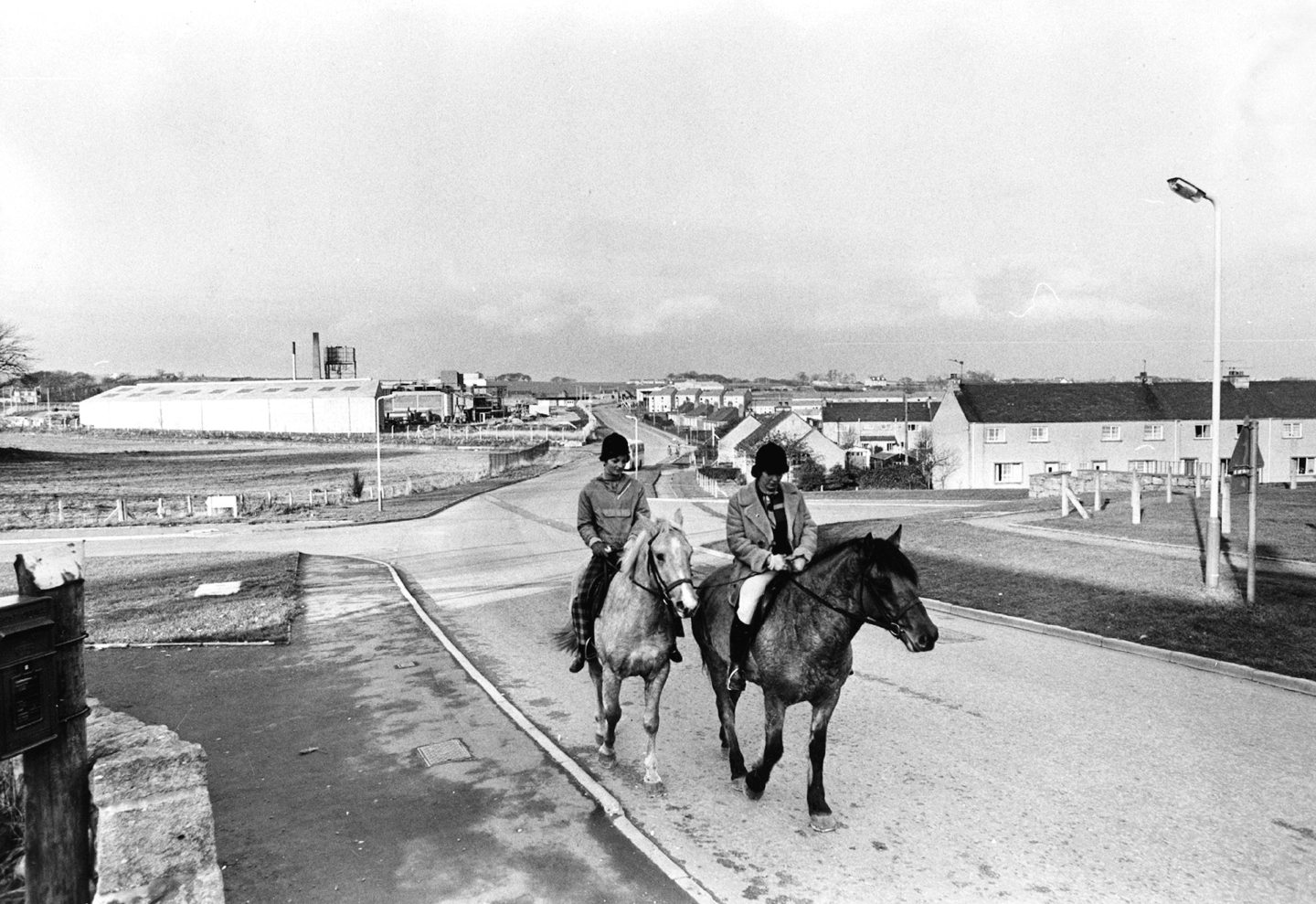

With its roots in agriculture and fishing, the traditional parts of ‘new’ Portlethen, once known as Portlethen Station, have long since been enveloped by progress.

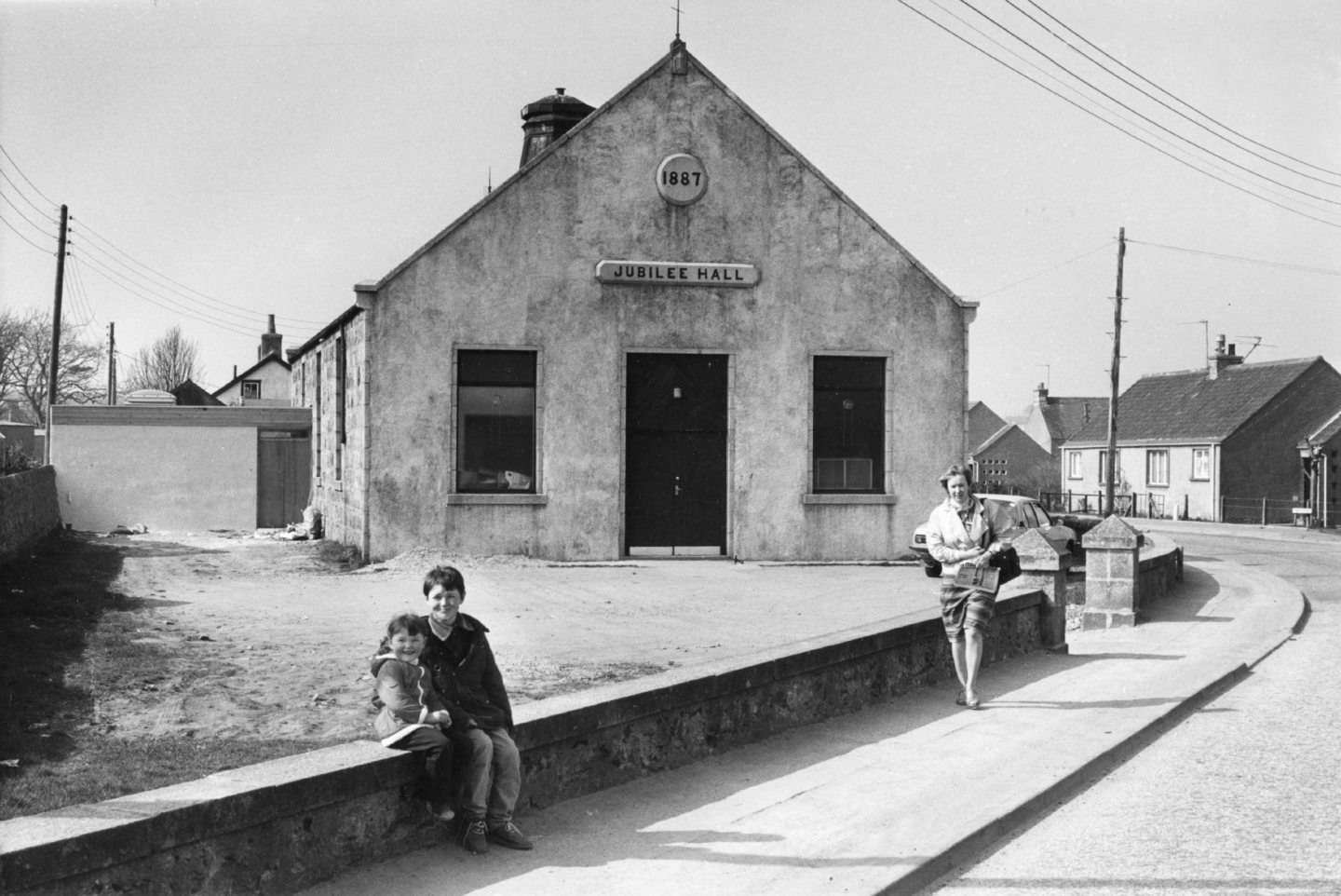

A smattering of old buildings like the kirk, Jubilee Hall and some old cottages remain in the community, but the Portlethen we know today was a product of the 1970s.

Any of the small communities could have been in line for expansion in the ’70s, but Portlethen Station, although it no longer had a station, seemed the natural contender.

It was close to the main road linking Aberdeen with the south, and had much more room to spread out.

Oil brought a huge influx of people to the area and the primary school was extended by another four classrooms.

By 1976, Portlethen was described by critics as “a no man’s land with houses abound, but no amenities”.

At that time there was only one shop and a post office, and residents were pressing for a community centre, chemist, bank, sports facilities and better roads.

Lands of Findon at heart of bloody battles for centuries

Meanwhile residents at Downies were relieved that plans to build 140 new homes in their quiet community had been withdrawn.

All but six residents in Downies had signed a petition against the scheme, wishing to keep their traditional village undeveloped.

The feeling was much the same in Muchalls and Findon.

Lands at Findon had been fought over for centuries, long before developers came knocking.

As far back as the 13th Century, Philip de Fyndon staked his claim on Findon and entered a dispute with the Monks of Arbroath over its ownership.

Tales of skulduggery and murder followed for years afterwards.

Fishing took precedence over farming, because the lands weren’t suitable for tilling until Dr William Nicol improved the area in the 1700s and encouraged tenants to reclaim the land.

Famous Finnan Haddies immortalised by Sir Walter Scott

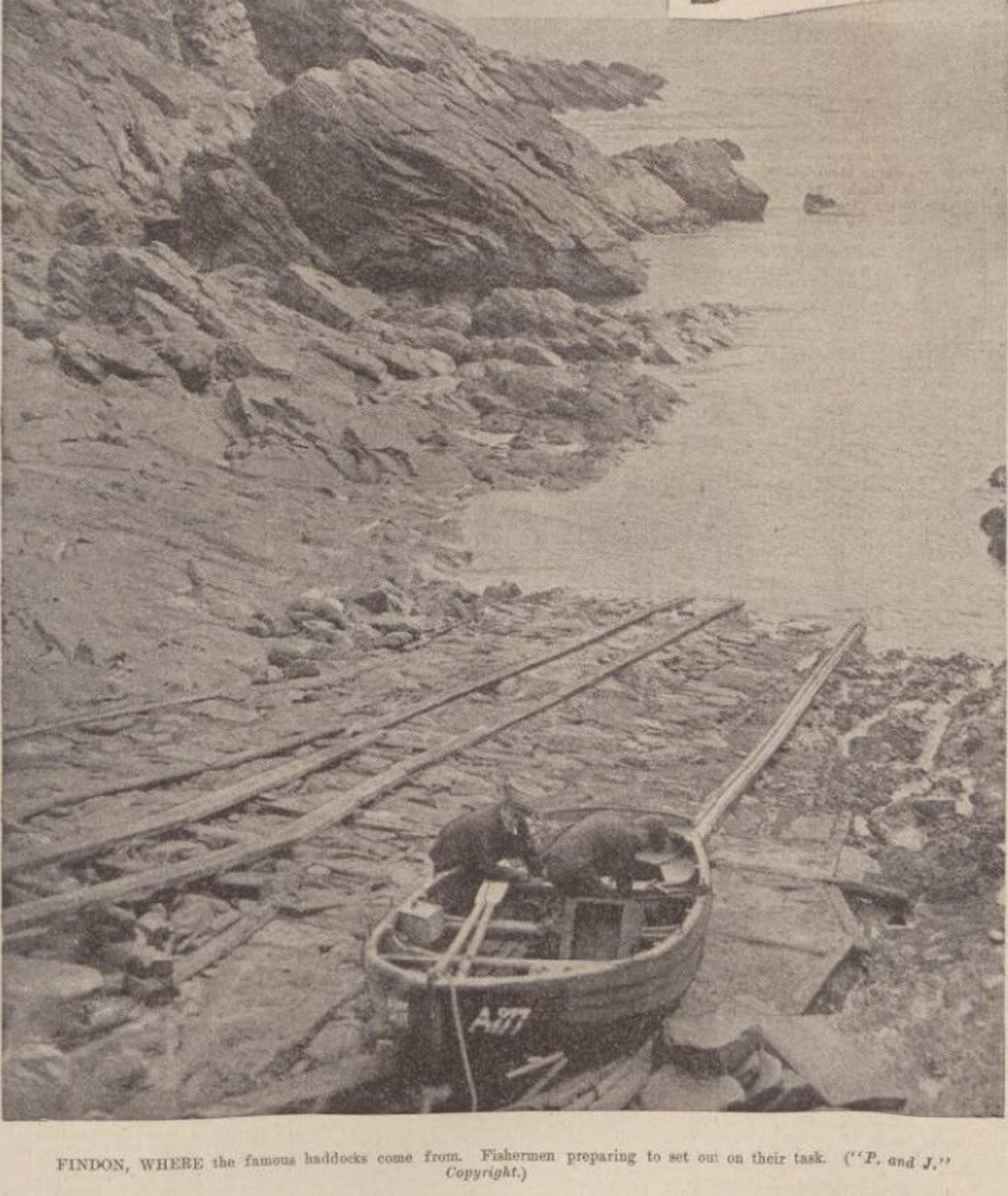

Findon didn’t have a large harbour; a fleet of around six boats was enough to keep two dozen fishermen in work.

But fishing is what put Findon on the map, or rather the Finnan Haddie did.

A gourmet’s haddock, it was a fish that had been “cured with smoke of green wood, peat or turf” and found international renown.

Sir Walter Scott enjoyed them so much he immortalised them in his works, writing: “A Finnan Haddock has a relish of a very peculiar and delicate flavour, inimitable on any other coast than that of Aberdeenshire.”

Their taste was attributed to high-quality fish caught by Findon men “in the clear water off their rocky little harbour”, cured by skilled villagers with peat from Portlethen Moss.

While the peat may have given the fish its distinctive yellow hue, it was often said the windswept air swirling around the clifftop village “may also have added something to the final taste”.

Gallery: Photos of Old Portlethen and district in days gone by

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation