The Prop of Ythsie is a striking monument near Tarves that commands pastoral views across the rolling Formartine countryside.

In recent months the tower has garnered wider interest after TV personality and sometime Aberdeenshire resident, Georgia Toffolo, listed it as one of her favourite dog walks.

For more than 160 years, the landmark has borne silent witness to the ebbs and flows, feast and famine of rural life and agriculture.

And while the conspicuous Prop of Ythsie could hardly be forgotten, the story behind it is gets more distant with every passing year.

This stern, granite tower is a tribute to pragmatic Haddo laird, former prime minister, diplomat and devoted father, George Hamilton-Gordon.

But his success in international politics and public office greatly contrasted with his personal life, which was stalked by tragedy.

Prop of Ythsie was erected by tenants to remember kindly laird

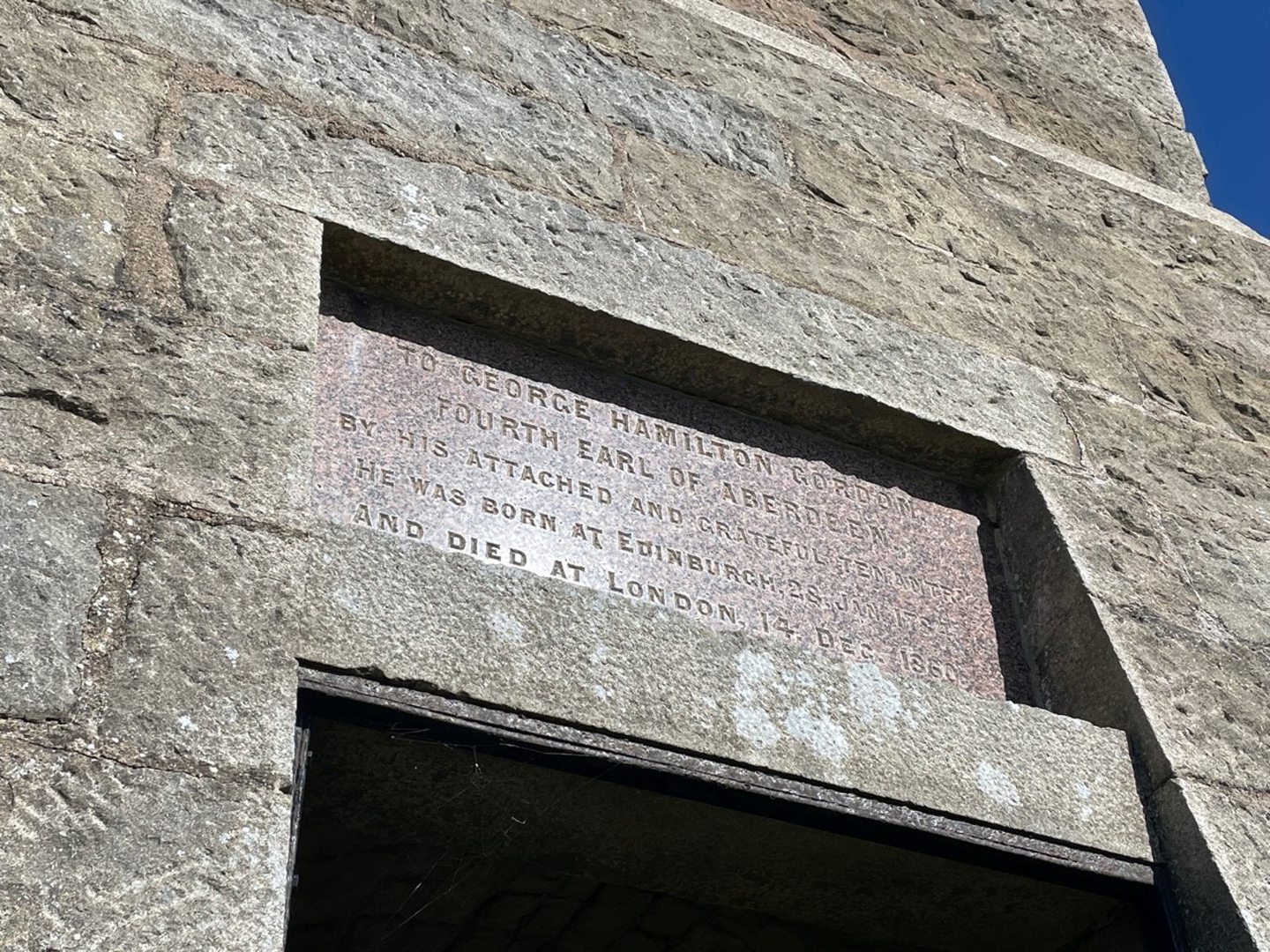

A stone’s throw from Tarves, the Prop of Ythsie was erected in 1862 in “grateful” memory of George Hamilton-Gordon, the 4th Earl of Aberdeen, by his tenants on the Haddo estate.

While such tributes were often made under duress, George transformed the lives of his tenants.

He was not like other aristocrats, or even like his forebears.

Although born into the wealthy and influential Gordon family, he later inherited estates and debts.

With little money to his name, George invested everything he had to improve the lives of tenants.

George’s life was more tragic than any poem written by his cousin Lord Byron

He was born George Gordon on January 28 1784, the eldest son of George Gordon, Lord Haddo, and Charlotte Baird.

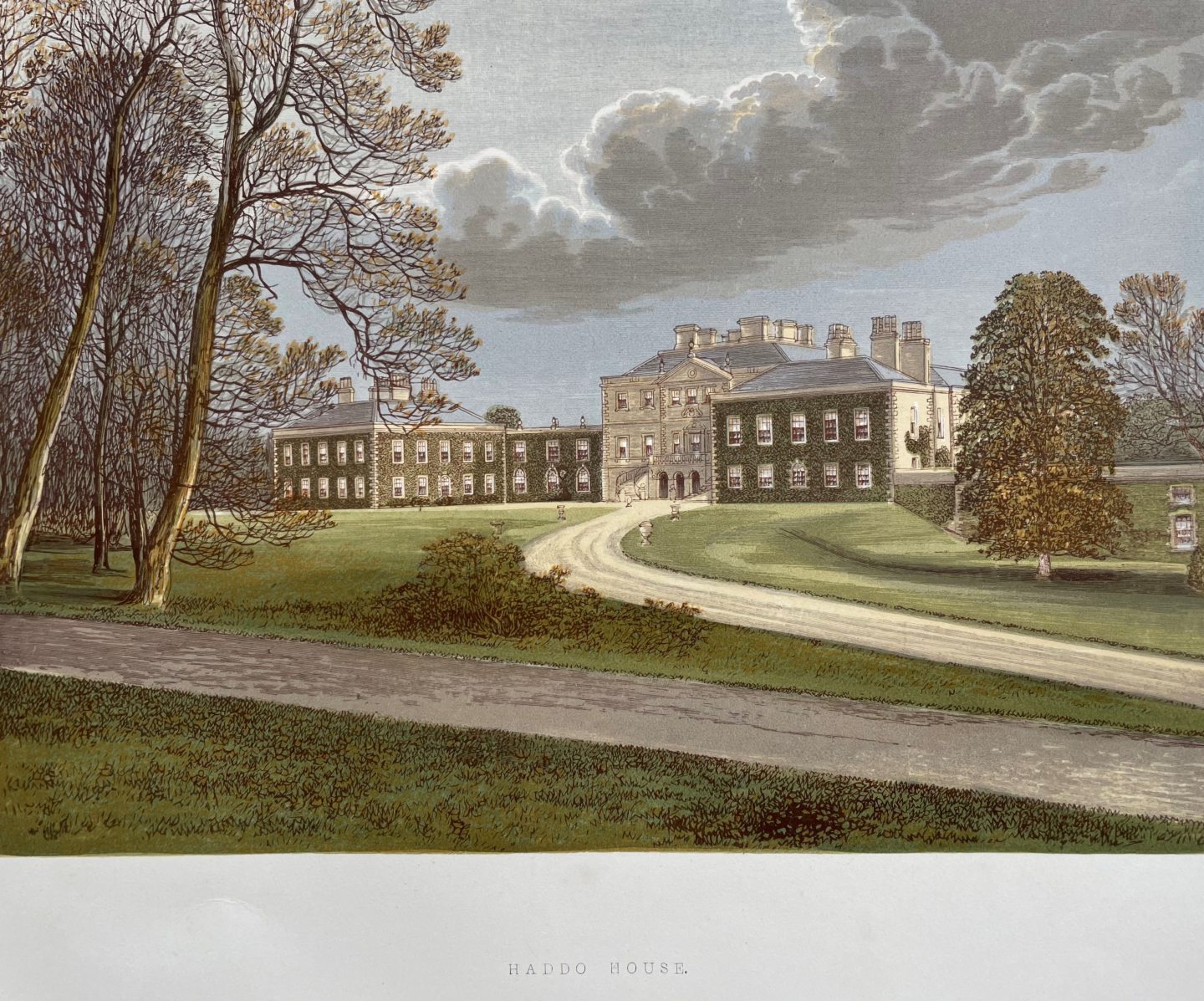

The family split their time between Haddo House and Edinburgh.

George was also a cousin of poet Lord Byron, to whom he bore a striking physical resemblance with similar curly black hair.

But the sadness that befell George’s life was more tragic than any poem Byron could have written.

His father died falling from his horse in 1791 when George was only seven, and his mother died four years later, leaving him orphaned at the age of 11.

Upon his father’s death, young George Gordon became Lord Haddo, and under Scots Law was able to appoint his own guardians.

He was sent to Harrow and raised by prime minster William Pitt the Younger, and the most powerful politician in Scotland at the time, lawyer Henry Dundas the 1st Viscount Melville.

Previous ‘wicked earl’ exploited Haddo tenants and left them in poverty

He was just 17 when he inherited the Earldom of Aberdeen from his grandfather George Gordon, the 3rd Earl of Aberdeen, in 1801.

He spent two semesters at Cambridge before taking the Grand Tour of Europe to excavate in Athens and learn about Greek architecture.

George had a penchant for Classics and was part of the controversial acquisition of the Elgin Marbles – something his cousin Lord Byron publicly berated him for.

But in 1805, when he returned home to Haddo House for the first time since childhood, he was appalled at how impoverished the estate tenants were.

His grandfather was known as “the wicked earl” for evicting tenants or exploiting them through 19-year leases.

Not to mention the multiple illegitimate children borne to multiple women.

As well as inheriting the earldom, George also inherited his father and grandfather’s debts.

George inherited father’s debts but wanted to improve tenants’ lives

The widespread destitution among the tenantry was at odds with his life in London.

His forebears had squandered money leaving George with little, but with what he had he invested in the estate and and agriculture to improve the lives of his tenants.

While he owned extensive land, the soil was very poor.

He became interested in new methods of farming, spending much time having land drained, cleared and cultivated.

Many decades later, the fertile, loamy land at Ythsie was still considered among the finest in the district.

George returned to London in 1805 aged 21 and married Lady Catherine Elizabeth Hamilton, to whom he was utterly devoted.

The following year he entered the House of Lords having secured an English peerage promised by Pitt, unheard of for a Scotsman.

George’s life spiraled into depression when beloved wife died

George’s home life was initially a happy one.

He and Catherine had four children; daughters Jane, Charlotte and Alice, and his only son and heir who died the day he was born.

In 1812, George joined the foreign service as a diplomat and helped organise the coalition that defeated Napoleon.

While he found political success, tragedy struck the same year when his beloved Catherine died from tuberculosis.

Bereft, George obtained a royal licence to take her surname, Hamilton, becoming George Hamilton-Gordon.

He spiraled into depression and wore mourning clothes for the rest of his life.

George was also haunted by the horrors of war he witnessed first-hand on the battlegrounds of Europe.

Tragedy struck again when his three daughters died before age of 20

With no male heir, a marriage was engineered by George’s father-in-law to marry his widowed sister-in-law, Harriet Douglas in 1815.

Their union was a deeply unhappy one.

George’s political ambitions took a backseat and he devoted his time to Haddo and to his children.

Harriet was unkind to George’s daughters from his first marriage, she despised Haddo and they lived largely separate lives.

But nevertheless they had five children, four sons including heir George (later 5th Earl of Aberdeen), Alexander, Douglas, Arthur and a daughter, Frances.

In another devastating blow for George, TB killed all of his daughters from his first marriage before their 20th birthdays; Jane at 17, Charlotte at 10 and Alice at 19.

Triumphant return to politics saw George made foreign secretary

In another blow, his youngest daughter Frances died aged 15 in 1834, and George was said to be so grief-stricken he could not attend her funeral.

Despite personal turmoil, George made a return to politics in roles including foreign secretary, twice, and secretary of state for war.

He was a favourite of Queen Victoria and earned a reputation as a respected diplomat internationally, although was a terrible public speaker.

As foreign secretary he tackled slave trafficking, settled disagreements with the United States, and improved relations with European nations.

George was also successful in pushing through domestic reform.

When Sir Robert Peel died in 1850, George became leader of the Peelites, a breakaway faction of the Conservatives.

When the minority Conservative government collapsed in December 1852, groups of Peelites, Whigs, Radicals and Irish banded together in opposition.

George became prime minister, but Crimean War ended his career

George became leader of this new Liberal group and took up office as prime minster on December 28.

He struggled to control several big personalities and rivals in his Cabinet, including career politician Lord Palmerston.

His own ministers often – and publicly – disagreed on foreign policy, and George himself was no negotiator, instead described as an honest man with integrity.

When the Crimean War broke out between Britain and Russia, George was held responsible for the mistakes made by his generals.

This ultimately lead to his resignation in 1855, but the guilt over the bloodshed ravaged him for the remaining five years of his life.

When George died in 1860 he was buried in a family vault at Stanmore in London, which was so full that his coffin was placed on top of Frances’.

Prop of Ythsie was built to honour memory of tragic laird

Back in Aberdeenshire, a monument was proposed to his memory on the Haddo estate.

Tenants raised funds for the memorial, which was to take the form of a 25-metre tall, square tower with parapets at Ythsie.

Completed in red granite in 1862, the Prop of Ythsie could be seen from across the earl’s estates.

Inside, 91 steps curl around to the top, providing views across tenant farms to Haddo House itself.

Now a category C-listed monument, the Prop of Ythsie underwent significant work in 1992 to make it more accessible to the public.

It remains a popular walk and viewpoint, and totem to a tragic laird who only sought to improve the lives of others.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation