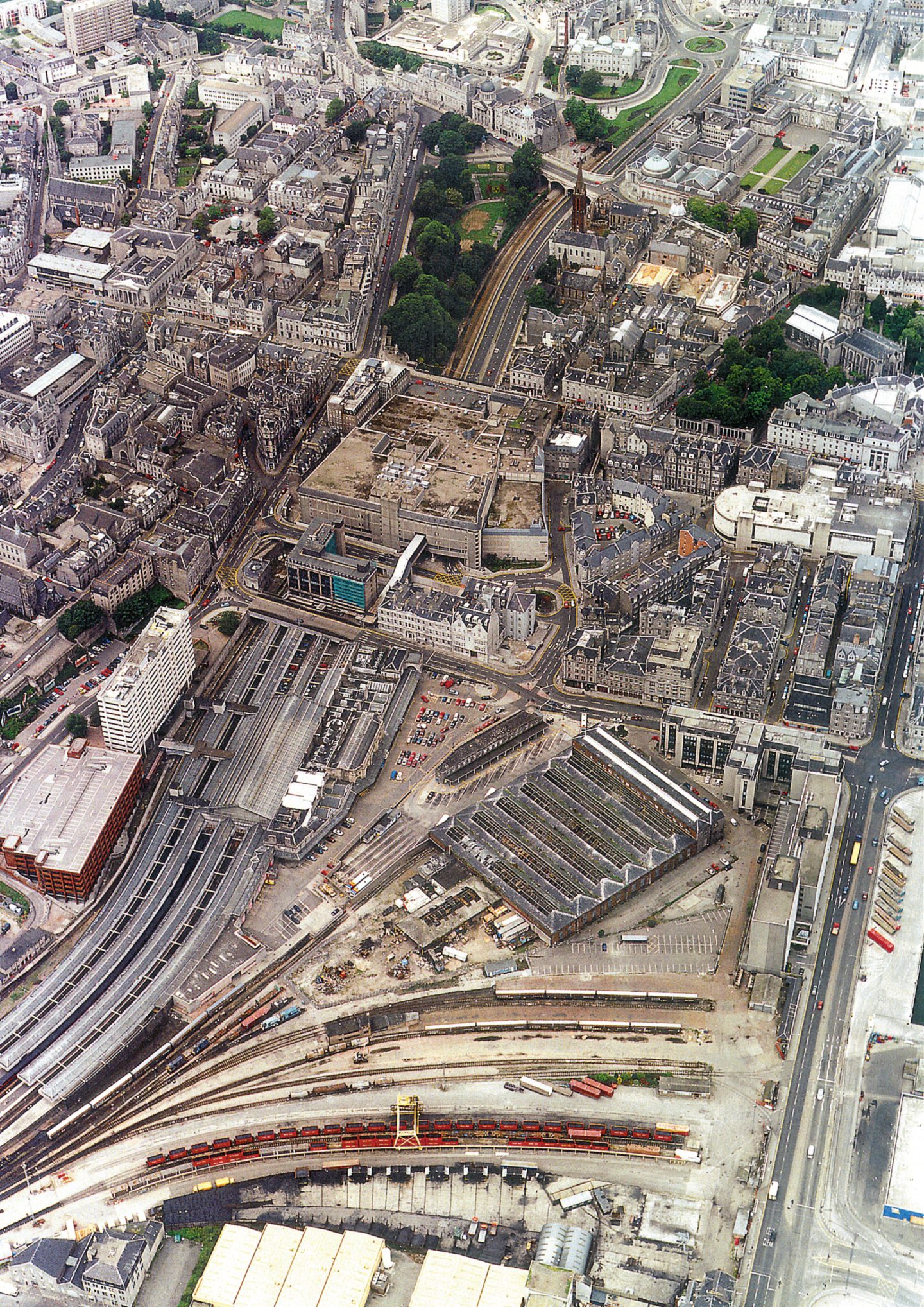

As Union Square celebrates its 15th birthday, it’s easy to forget the hurdles planners faced when developing the run-down Guild Street site.

Far from being a straight-forward build on an industrial wasteland, developers faced a decade-long battle to make their ‘retail paradise’ a reality.

Plans were first unveiled for a multi-million-pound retail and transport terminal in the heart of Aberdeen in 1997.

But read on to find out :

- Why it would be another 12 years before the doors of Union Square opened

- What was there before

- And which Gothenburg Great almost had his name enshrined as the name of the shopping centre…

What did Guild Street look like before Union Square development?

It was proposed to link the Guild Street bus and railway stations with restaurants, bars and a covered shopping arcade.

Most of the land was owned by the council and Railtrack, who teamed up with Glasgow-based Stannifer Developments.

Home to Railtrack’s freightliner depot, it was dubbed “Britain’s most undeveloped city-centre site”.

But the depot was a huge obstacle to overcome. It was to be split and moved to two centres – Raith’s Farm, Dyce, and Craiginches.

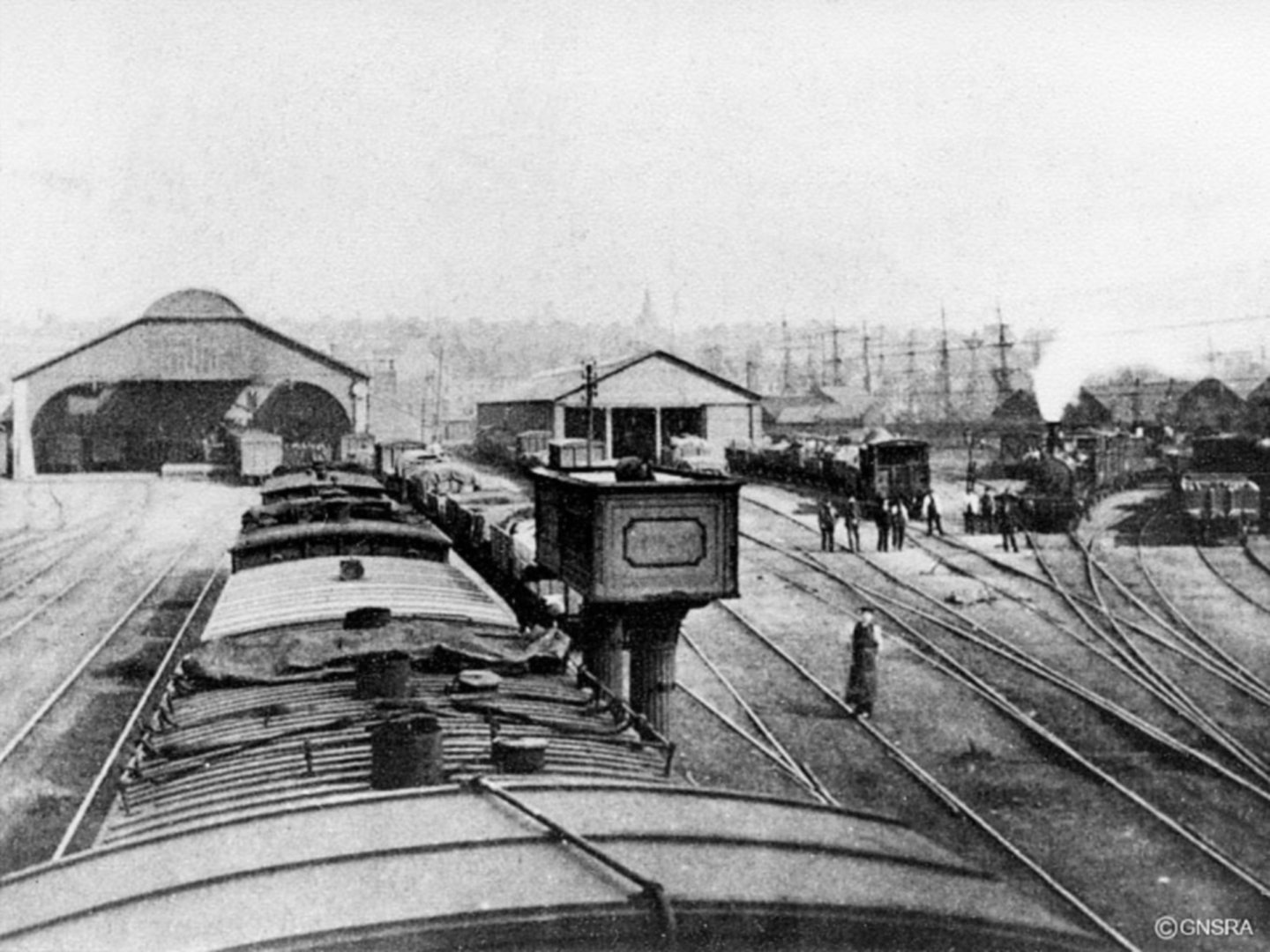

Guild Street Goods Yard opened in 1850 as part of the original Aberdeen Guild Street Railway Station, before the Joint Station opened in 1867.

Previously, trains from the south terminated at Guild Street, while trains from the north terminated at Waterloo Quay.

Passengers were transported between stations to make connections.

The Joint Station opened in 1867, replacing Guild Street and Waterloo Quay, making Aberdeen a through and terminus station.

Historically, the railway goods yard connected the station with the docks.

Horses pulled wagons of fish along harbour rails to the freight depot, where they’d be loaded onto trains at the old sidings.

A hive of industry, to keep up with commercial and passenger demand, the station was rebuilt circa 1915, incorporating the original train shed with a new facade at Guild Street.

It was the last major Scottish railway station to be built, and was to be retained as part of the Union Square blueprint.

But the dilapidated freight depot, which was closed by British Rail in the 1970s, would disappear under the plans.

Guild Street site played important role in Aberdeen’s transport history

Guild Street was a major railway site, but was also home to Aberdeen’s busy bus station for 45 years.

When the bus station opened by the Joint Station in 1963, it was said road and rail were brought together “harmoniously” on one site.

But to make way for it, historic infrastructure was removed including the old weigh house for the fish-loading at the Joint Station.

As well as the city and regional services, the bus station was a terminus for coaches from the north and south of Scotland.

Just a stone’s throw from the harbour, the bus stances felt like the coldest place on Earth in winter.

But the bus station did have a waiting room and left-luggage store, with offices and canteens for staff above.

It was also to be demolished to make way for the new shopping complex.

Guild Street, already populated by transport and offices, was described as “the last decent bit of land in Aberdeen city centre”.

1997: Shopping centre plans would make Aberdeen a ‘showcase station’

Part of the desire to build Union Square was to create a “showcase” station in Aberdeen, according to Railtrack, the successor of British Rail.

Railtrack was a group of companies which owned much of the railway infrastructure, before it fell into financial difficulty in 2002.

Overhauling the station was a top priority for the group in 1997.

A spokesman explained: “In most cities we have a large showcase station which welcomes travellers and shoppers but that is not really the case in Aberdeen.”

He added the development would “give the city one of the very best transport terminals in Britain”.

Proposals took a step forward in 1998 when plans were submitted to create a railhead and industrial-use complex at Raith’s Farm.

Railtrack spokesman Simon McMillan said freeing up the Guild Street freight yard would make room for “a civic square with shops and pedestrianised areas”.

1998: Costs rose before plans were finally lodged with council

One of the major considerations for council planners was traffic flow on what was already one of Aberdeen’s most congested streets.

In 1998, the estimated cost was up to £100 million and the opening date was pushed back to 2002.

But with the development of this vast, 19.4-acre site came the tantalising promise of city-centre regeneration and 1500 new jobs.

It was to be a state-of-the-art leisure, retail, hotel, superstore and restaurant development, complete with a multiplex cinema.

The ambitious plans were the jewel in the crown of a wider revival to “kick-start” the local economy.

And Christmas came early for stakeholders in December 1998, when plans were finally lodged with the council for “Scotland’s biggest transport, retail and leisure development”.

By now, predicted costs had crept up to £120m.

At the heart of the complex was to be a “breathtaking public square” linking the Victorian station with its modern bus counterpart.

Councillors duly approved the plans in March 1999, making Aberdeen the first UK city to provide a fully integrated combination of travel, retail and leisure services on one site.

1999: Further delays as key organisations raised concerns

But come August 1999, as disagreements raged and progress stalled, Union Square was hit by rival plans.

Councillors approved a large retail park off Aberdeen Beach Boulevard; a Premier Inn off West North Street, and a £12m multi-screen cinema called The Lighthouse on Shiprow.

Before a single spade even touched the ground, key organisations began to raise concerns.

Aberdeen Chamber of Commerce felt Guild Street could not cope with more traffic.

While the Harbour Board said removing rail freight was detrimental to the harbour “at a time when many harbours, including Aberdeen, are seeking to improve rail links”.

The Bon Accord Centre and John Lewis both raised grave concerns the complex would draw trade from the city centre.

A development plan departure hearing was called in November to further scrutinise proposals before it passed to the Scottish Government to have its say.

When the Scottish Executive delayed making a decision on Union Square for a third time, serious doubts began to set in.

2000: First Minister Donald Dewar finally rubber-stamped Union Square

But there was relief in 2000 when the ambitious Guild Street development overcame its last major hurdle and First Minister Donald Dewar approved.

Stannifer could now proceed with its “shoppers’ paradise” – as long as Historic Scotland signed off on alterations to the Victorian station.

Then council leader Len Ironside described it as “super news for the city”.

But there was a further setback in 2001 when Aberdeen Harbour Board disputed land behind the station.

The site was sold by the harbour board more than 100 years before, with a sell-out clause stipulating ground must only be used for rail purposes.

It was only when the case went to the Scottish Land Tribunal that developers were finally given permission to proceed.

And soon thoughts were turning to what the new complex could be called.

Some Aberdonians suggested it could be named after King Robert the Bruce to reflect his gift to Aberdeen.

Others felt it should have been named after Donald Dewar who died suddenly in October 2002 in a nod to his time as an MP in Aberdeen.

Another suggestion was Willie Miller Square after the Dons star.

2003: Demolition began on historic railway sheds ahead of development

But in the end, Union Square was chosen, although it was not popular.

One reader’s scathing letter to the Evening Express said: “Union Square is an entirely inappropriate name for the new development, which has nothing to do with Union Street, except possibly to make it even less viable than it is at present.”

But the name stuck, and finally on November 28 2003 demolition began on the old railway sheds.

Councillor Ironside welcomed progress to transform Aberdeen’s last city-centre brownfield site.

He added: “If Guild Street is the first impression you get of Aberdeen when you come off the train, it’s disgraceful.”

By 2004, excitement was building as retailers like Zara and TK Maxx signed up for vacant units.

But although demolition had been ongoing, construction had not started.

2007: Foundations finally started going down as costs soared

By April 2005, work still hadn’t begun on Union Square and costs had crept up to £160m.

Developers still hoped to complete the build by 2007, but said 2008 was more likely.

Director of property Alan Bell said: “We realise that seeing is believing. We would be the first to admit it’s taken longer than anticipated – it’s been quite difficult getting through the morass of railway regulations.”

Stannifer was bought over by a new backer, Multiplex Developments, and spring 2006 was agreed as the new start date.

But it would be 2007 before work began – five years behind schedule – because of problems clearing the freight yard at Aberdeen Station.

The foundations of the 700,000sq ft retail and leisure complex were laid in March, but as the building’s bones went up, so did the costs.

The bus station was finished first, with Stagecoach taking ownership from February 2008.

But there was a last-minute curveball in June when the council decided the development should be renamed Guild Square after the city academic Dr William Guild.

He was a former principal of the city’s King’s College whom Guild Street was named after.

But that didn’t curry favour with EE readers either, with others suggesting St Magnus Square was more appropriate to “raise memories of the ferries to the Orkney and Shetland Isles”.

2009: Delight as 58,000 eager shoppers swarmed Union Square on opening day

Ultimately Union Square stuck, and on October 29 2009 when eager shoppers queued up to get a first glimpse of the long-awaited mall, nobody cared what it was called.

In fact, anticipation built so much, police were concerned roads wouldn’t cope and Aberdonians were urged to leave cars at home.

More than 40 extra police officers were drafted in to monitor traffic levels and control the crowds.

Free shuttle buses were even put on between Union Square and other parts of the city.

Some shoppers had been queuing since 8am to get in – four hours ahead of its noon opening.

At one point security staff and police intervened to stop a crush as shoppers surged towards the premises.

When operator Hammerson’s chief executive David Atkins cut the ribbon at the entrance of the £275 million mall, thousands “swarmed” in.

And it was revealed 58,000 shoppers passed through its doors in the first eight hours of trading – the 11-year wait had apparently been worth it.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation