Part one: The early 80s and the rise of Brian Beattie

(Listen to this section as audio)

Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall was still number one and Aberdeen FC were starting the second half of a season that would ultimately see them crowned champions of Scotland.

January 1980 heralded the start of a new decade. A decade that was to see huge social upheaval in politics, fashion and the music scene. But it would also see the arrival of drugs to Aberdeen and the rest of the north-east, bringing with them organised crime, violence and a dramatic shift in police tactics across the region.

The decade had started in a relatively quiet fashion. Police in Aberdeen saw little in the way of mass drug taking, large-scale addiction or organised drug dealing. Sure, cannabis was smoked but only on a small scale, while amphetamine was seen from time to time.

But class A drugs, such as heroin and cocaine, were rarely in circulation. One former Grampian Police drugs squad officer, who began his police career in the late 1970s, said: “When I joined the police my impression at that time was that the only drugs of any consequence were cannabis or amphetamine: speed.

“There was no heroin, cocaine and we didn’t even know what crack cocaine was. LSD was around but it was on the way down. It had trended itself out. Cocaine and heroin were your big city drugs.

“You had the odd heroin addict but they were known. They were so unusual you knew who they were.

“They would have to travel to the likes of Liverpool to get their drugs. It wasn’t a lucrative trade. They were just supporting their own habits.”

Policing at the time reflected the size of the problem and the tactics were straight-forward, if rather rudimentary. Officers would hear drugs were being used at an address, get a warrant and raid the place.

The officer added: “It was a bit back-of-the-fag-packet back in the day: let’s get a warrant, kick the door in and see what we get.”

But by the early to mid-80s the drug scene started to change. Some experts cite the de-industrialisation of Scotland as being partly to blame, creating high unemployment and a generation of kids with little to look forward to. A ripe market for heroin being farmed in Afghanistan, cannabis from North Africa and, eventually, cocaine from the jungles of Colombia.

But Aberdeen was more complicated. And that was down to oil.

The former senior drug squad officer said: “The city became cosmopolitan quite quickly with the oil money coming in, Americans coming in. I’m not blaming Americans but you had lots of different people coming with different philosophies and previous exposures to drugs.

“I can’t prove this but when you look at oil drillers, back then you had people working 24 hours and 48 hours on the trot. You’ve got to be crazy if you didn’t think they were taking amphetamines. If you go back through the history of drugs even the military would give paratroopers and pilots amphetamines.

“The oil, the growing wealth and the disposable incomes led to a good marketplace which was rich for picking.”

As the market grew, dealers became more organised, setting up along the lines of any other business.

The principles were simple: establish a network of trusted people you can sell to, establish a source for your product, then make sure you work from “a mother stash” in a rural location so, if you’re caught, you don’t lose most of your supply.

And then there was the tick list – a dealer’s paper record of who bought what and how much they paid or owed. In an age before mobile phones and WhatsApp, the tick list was like gold dust to drug squad officers. Find the tick list and you were on to a winner.

Forces were also starting to understand that they needed to use informants to build intelligence on the growing number of dealers. Arrest someone, go down to the cells, have a chat, offer them some cigarettes and get to know them a bit. Then you might start to get some information that could lead you up the drug dealing chain.

In 1982, one man sat at the top of that chain. Brian Beattie, dubbed Aberdeen’s first drugs baron.

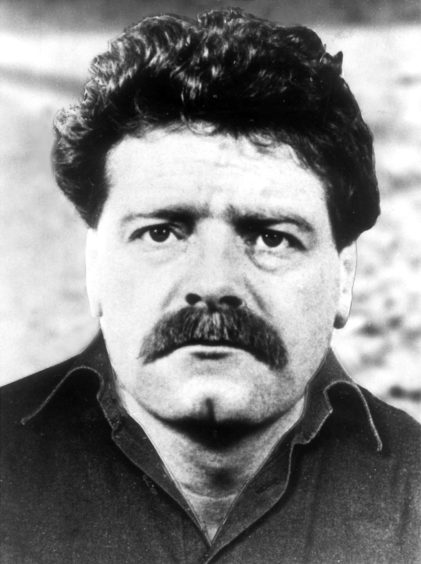

Brian Beattie: Aberdeen’s ‘first drugs baron’

Beattie, from Kincorth, was a man already at odds with the law, known by police for poaching salmon. But Beattie, the eldest of a family of three boys, soon discovered there were other more lucrative ways of making money – drugs.

His empire started slowly, with cannabis and speed his products of choice. However, it wasn’t long before he was selling heroin; highly addictive therefore highly profitable.

His local bar, The Covenanter, became his base – and business was good. At the time Aberdeen had very few heroin addicts but Beattie made sure that figure started to rocket.

Beattie, who cut a striking figure with his walrus moustache, was almost idolised by teenagers in his local area who became part of his mob and his customer base. One officer involved in the operation to bring him down said: “He was quite articulate, smart and clever. He was basically able to manipulate them.

“He was probably the kind of guy — and he wouldn’t be the only one involved in drugs to be like this — who, if he had turned his hand to legitimate business and commerce, he probably would have been pretty good.”

Beattie sold drugs at his local, at his home in Kincorth, the community centre, nearby houses, and waste ground while the nearby Gramps grassland was the perfect site for hiding his “mother” stash.

As business grew, Beattie’s gang included Graham ‘Pot’ Duncan, a 31-year-old who went from a well-paid oilman, fitness fanatic and a happy marriage to heroin addict and Beattie’s minder.

Beattie had contacts across Scotland and as far south as London, where he’d send addicts to pick up his gear then transport it back up the road to be sold on the streets of Aberdeen. He was at his peak between 1982 and 1984, selling hundreds of thousands of pounds of drugs each year.

He was also known for his luck in evading justice. He and Duncan once turned up late to a drugs meet at the Holiday Inn in Bucksburn, shortly after police had raided the premises arresting London couriers and finding drugs stashed in a hotel room.

But, as with all empires, his domination began to crumble, and when it finally did it did so in spectacular and bloody circumstances with his henchman Pot Duncan the root cause.

A fatal blow

Duncan was a human time-bomb prone to explode for no reason. One retired officer said: “I always found him reasonable to deal with but he seemed to change. I suppose, maybe, it was his drug abuse. He certainly started to get a reputation for being short-tempered.

“He could blow quite quickly and was a powerful guy. He was certainly prone to violence as time moved on.”

But one man wasn’t afraid. George Ritchie had stood up to Duncan and his boss, having seen the devastating impact drugs had on his own two sons. After a year or so of feuding with Beattie, he finally incurred the wrath of Duncan.

Four days before Christmas 1985, after going out for a drink in his local bar, he was knifed to death by Duncan as Beattie, who was on his way to deliver Christmas presents to his ex-wife, looked on.

Duncan had pulled Ritchie from his seat in the bar, before stabbing him three times with a carving knife. The fatal blow punctured a lung and an artery, leaving Ritchie slumped between some pool tables.

Beattie, Duncan and another man all denied murder when they appeared on trial at the High Court in Aberdeen in March 1986. But in a sensational move, Duncan changed his plea to guilty while Beattie and his fellow accomplice had not guilty pleas accepted by the Crown.

However, the north-east’s first Mr Big didn’t walk free as he had confessed to a string of drug dealing charges. He was jailed for 17 years while Duncan was given life for murder.

Beattie’s void was quickly filled by others. A retired officer said: “Others replaced him, the market was bigger and the opportunity to make money was bigger. If he hadn’t been caught he would have continued, grown and expanded.

“But you can’t really do that when you are in prison, which is one argument that prison works.”

Part two: The 90s and Ronnie Cormack

As the 80s ended and the 90s began, the drug scene exploded. The arrival of the rave scene created a new generation of users – Generation X teenagers from across the social spectrum. Drugs were no longer the preserve of the upper classes with their cocaine or those in the poor schemes with their heroin. No, they went mainstream with the arrival of ecstasy.

Every weekend, house parties and dance nights were being held up and down the country. Some even appeared in fields, where kids gathered around just a set of decks, speakers and lights. The boom in ecstasy created a huge rise in the number of dealers. Some sold to pals while others saw it as an easy source of money. As a result, the amounts of drugs entering the area rose exponentially.

A former senior officer said: “It was permeating all levels of society. It was not just city centre pubs, it was anywhere and everywhere across all areas. It started to become an issue in schools, schools in Aberdeen, where drugs started to become available and be sold.”

Dealers didn’t just sell ecstasy. They sold LSD, speed, cannabis and cocaine – why limit yourself to one product when you could offer four or five and increase the potential for profit? And some sold heroin, which would have a devastating impact on the area. Huge increases in drug seizures across the board reflected the change in society.

And heroin’s comeback quickly morphed into a massive problem for Grampian Police.

Another former drug squad officer said: “Heroin wasn’t like cocaine. Cocaine was almost seen as an acceptable drug in parts of the upper circles, the West Ends, if you like.

“No … heroin was a dirty word, heroin is smack. It correlated with death and addicts lying about streets, needles in playparks.”

Policing had to change to keep pace. Out went the kick-in-a-door-and-see-what-you-get approach and resources increased. At one point in time Grampian had just two full-time drug squad officers but that eventually rose to 14, with dedicated surveillance capabilities.

Informants became increasingly important. A drug squad officer would be expected to have a good network of informants prepared to share information, which some did for cash payments, sometimes for as much as a £100 a time.

That human intelligence would then be used to build a bigger picture of a dealing operation as did physical covert surveillance which involved undercover officers sitting outside properties, tailing cars and, at times, using wire taps.

So, now, if officers learned about a house party they didn’t rock up with dogs and a warrant. They didn’t just kick the door in. They watched and waited to see who attended and who they might be connected to and who was further up that chain.

Another ex-officer said: “Most of the drugs operations at that time came from information from people who were either on the inside or on the periphery of something. Some of the top informants were getting quite well paid.

“They were incentivised to do it. It was quite an exciting time as it was quite shadowy, meeting folk in the dark at night on a one-to-one situation.”

Now the police focus was firmly on taking out major supply networks and making as big seizures as possible. Instead of being happy with grammes and ounces they wanted headline-grabbing, and supply-disrupting, kilos.

And in the early 90s officers learned of one man who was moving drugs on that scale: Ronnie Cormack.

Ronnie Cormack: The Rosehearty gangster

Ronnie Cormack. A name that went on to dominate crime story headlines in the 1990s.

A former oil worker, he had a history of violence dating back as far as 1982 when he was involved in a vicious mugging.

But he really came to prominence in 1993 when officers picked up intelligence suggesting he was involved in drug dealing on a serious scale.

At one stage his operation was said to have had a turnover of £1 million a year, and was linked with moving 55 kilos of cannabis. He also sold heroin, cocaine and ecstasy with impunity given his fearsome reputation for violence left many scared to turn on him by giving evidence to police.

In one incident, the Rosehearty gangster threatened to kill a builder near Potterton in a dispute over money. He put a pistol to the man’s head then forced a bullet into his mouth.

One former officer, who was involved in the operation targeting Cormack, said: “We got intelligence that there was this guy who travelled into Aberdeen every day, doing lots of drugs, and had access to premises down by the harbour in Shore Lane.

“Cormack was unscrupulous. There were certainly threats of violence, of weapons to be used or could be used. He was surveillance conscious, difficult to deal with and difficult to catch.

“It was difficult to put values on what he was doing. Some people reckoned a million a year, it might have been half a million or even £1.5m.

“He certainly seemed to be a huge step up from the Beattie level but it was a different time in society. The market had grown and expanded, cocaine was starting to come in.”

Cormack’s actions made him the number one criminal target in Grampian at that time, also attracting the attention of the Scottish Crime Squad, an elite group of officers whose job was to pursue major figures in organised crime.

They launched Operation Haven which eventually ran to 21 months and cost the taxpayer up to £1 million. In such operations detectives often target potential weak points in a criminal operation. By taking out couriers you might force the main man to become more hands-on in his empire and start handling supplies, making it easier to catch him in the act.

The officer involved in the operation said: “You build up your intelligence and start looking for your opportunities. As smart and as clever as they are, if you start to work away you will start to identify little gaps and build on these. You’re trying to force a way in and I suppose trying to eventually force a person to go hands-on.

“If you can successfully target some of the runners and they are in prison, then he (the main man) is potentially out of money to the person from whom he purchased the drugs. He has to make that back and the thinking goes that you force him to go up front himself but that could take months or even years.”

In Cormack’s case the months of hard graft had reached a critical point. Was it now time to strike? All sorts of factors add up to making that decision: do you have enough evidence? The mounting cost of the operation, and the threat posed by the target. In Cormack’s case that was a prime consideration given intelligence emerged he had a machine gun.

Our source said: “If you’re a senior police officer and you’re being told by your drugs squad that this guy is supposed to have access to a machine gun, you are thinking ‘Oh my goodness, how long do I let this run because if this gun gets set free on Union Street on a Friday night I know about it and I haven’t done anything about it?'”

Armed raids across Aberdeen

On the morning of December 16 1994, officers raided Cormack’s home and executed 23 search warrants at a string of properties across the north-east. Heroin, cocaine, cannabis, and ecstasy were found at a house in Dyce. Three sawn-off shotguns and a stun gun were also found during the raids, which at the time were part of the biggest drugs operation yet mounted by Grampian Police.

At the High Court in Aberdeen, Cormack was jailed for 17 years. But that was not the end of the story as just a few months later he hit the headlines again this time as the star witness in one of the north-east’s most dramatic crime stories.

On the morning of January 11 1995, two Grampian Police officers were arrested in a major corruption probe which had begun months earlier.

The investigation centred on allegations that Cormack, while at his drug dealing height, had been tipped off regarding police activities by rogue officers in exchange for cash.

Only one officer eventually made it into the dock, where he was accused of corruptly accepting £6,000 and other payments from Cormack for giving him information about police operations. He was also accused of failing to fully investigate the involvement of Cormack, and others, in a house raid, then passing information to one of the suspects.

He was also accused of failing to fully investigate a firearms assault by Cormack and another, then telling them to dispose of any firearm and how to answer any police questions.

During the trial Cormack gave evidence, telling the jury: “I don’t have anything against police officers in general, but there are some police officers who are bigger criminals than those walking the streets”.

The officer strenuously denied the charges and the jury took just over three hours to clear him. After the case, he ultimately walked free, described his ordeal as a huge strain before adding that he was “off for a pint”.

Part three: Bringing down THE Mr Big

As the 90s continued, and despite the arrest of major players such as Cormack, the flood of drugs didn’t stop. Heroin was still a massive problem. Crime in Scotland was peaking around 1998. After all, addicts needed to fund their habits. Shoplifting, armed robberies, and house break-ins were all common sources of cold, hard cash.

But it was the human cost that struck hardest. Drug deaths were now common but the victims were not just confined to older addicts whose bodies had given up the ghost. The dead included young people, some in their teens, some in their 20s, some with kids.

One retired officer said: “I remember being called to an address in Northfield. We’d been told a neighbour could hear a bairn crying. We forced our way into the house and there was a couple sat on a couch, both dead with needles in their arms, and a bairn sitting in the playpen in the middle of the floor.”

Despite the growing death toll, the approach to tackling the problem was still disjointed even if police forces across Scotland were starting to work together to take down major players.

One ex-officer told how he had gone public to warn of a dangerously pure form of heroin that was being linked to drug deaths.

The chief constable of the time was then inundated with calls from politicians and councillors saying the force was giving out the wrong message and painting the area in a bad light.

Despite such protestations, Grampian Police decided to embark on what would become its most complicated, challenging and boldest operation to bring down the man said to be flooding Grampian with heroin … James Hamill.

Catching James Hamill

James Hamill was the archetypal Glasgow gangster. He was flash, arrogant and boasted to police that he had links with a major London mobster and that he knew rock stars Oasis.

The unemployed pipe fitter was at the top of the criminal pile during the mid to late 1990s. He wasn’t daft either. Instead of risking potential clashes with other organised crime gangs in his home city, he decided to find a market that was ripe for exploitation without the fear of competition.

That market was Aberdeen. And over a period of just 11 months police believed he was responsible for flooding the area with as much as £4.5 million of heroin. Police said that Hamill and his gang were responsible for half of the heroin that was flooding into the city to feed an ever-growing army of addicts.

While many suffered, Hamill enjoyed the high life. He had two homes in Glasgow, one a four-bedroom property, drove a Mercedes and was a shareholder in his beloved Celtic FC. Trips to the Continent, including Belgium, as well as North Africa, were not uncommon. Most of his illicit profits went towards funding his extravagant lifestyle. His phone bill alone was £400 a month.

But going after Hamill was a gamble. In fact, it was the first time the Grampian force had gone after a dealer who didn’t live on their home turf.

Back then, while forces did co-operate, there was still huge rivalry between drug squads over who “owned” a specific criminal and who got the kudos of bringing him down. In some cases, couriers wouldn’t be taken out in another force’s patch. Instead, they would be allowed to travel back to their own city so the home force could get the scalp.

One source said that as they investigated the major supplies coming in from Glasgow one name came up.

“Back then there was a recurring theme … Hammy, Hammy, Hammy. We linked up with Strathclyde Drugs Squad and very quickly realised we were talking about James Hamill. This was a guy who had been through at least one High Court drugs trial where he’d been cleared.

“He largely did see himself as being untouchable. There was a huge amount of scepticism from the Strathclyde Police that a parochial drugs squad like Aberdeen could get a guy like Hamill.”

However, the involvement of the Scottish Crime Squad, which investigated organised crime at the time and had a couple of Aberdeen officers assigned to it, proved pivotal. They were “highly motivated” to get the squad involved in helping Grampian to bring down Hamill.

Part of the politics involved the Grampian Drug Squad having to “flag up” Hamill and get permission to “own him”.

Our source added: “So if, for instance, Strathclyde had owned Hamill then we would have to go after him with their co-operation. But nobody had Hamill.”

A pattern of behaviour

Senior Grampian officers then scoped out the size of the challenge that potentially lay ahead and whether they were happy to take it on, while weighing up the risk other cases would have to take a back seat.

Our source said: “We had to sit down and say ‘Right do we really want to take on Hamill?’. This was a big decision as you knew you were potentially taking on a year-long, or even longer, intelligence-gathering operation.

“You’ve got to have your evidence in the bag. You have to work on the premise that when you arrest the top guy they won’t be sitting at home with bags of money or drugs. You will take them out when they are probably out shopping with their wife.

“You know these guys are not typically hands-on so you know before you go anywhere near them you are going to have to have gathered all the evidence linking them in through direct testimonies from sub dealers or surveillance.

“You’ve got to be careful what you wish for because if you take on a target of that magnitude other things are going to suffer.

“One school of thought might be that we had bitten off more than we could chew. Some drugs squads were quite parochial and would focus on the street dealers in their own areas so there was a lot of scepticism that we would ever get him.”

Despite the fears, the force pushed on and the intelligence picture began to build.

Aberdeen was the only city Hamill was targeting, with three couriers a week travelling from the north-east to Glasgow to pick up supplies. They were put up overnight in hotels before meeting Hamill or one of his team at his favourite rendezvous: outside RS McColl in George Square.

He would tell them to put their cash in his “safe”, which was the glove compartment in his car. The courier was then driven to an industrial estate where drugs were exchanged before they made their own way back to Aberdeen.

Massive surveillance was launched at both ends of the country. The north-east effort alone ran for the best part of a year with officers taking out nine couriers during that period. Detectives said it was vital that those couriers were only arrested when they got as far away from Glasgow so Hamill’s suspicions wouldn’t be aroused. Officers said that in a year they seized around £1.5m of heroin… But as much as £3 million more escaped their efforts.

Timing was critical. To bring down a dealer of his scale they had to build evidence, persuade couriers to turn against him, and establish a pattern of behaviour that showed he was indeed the top man.

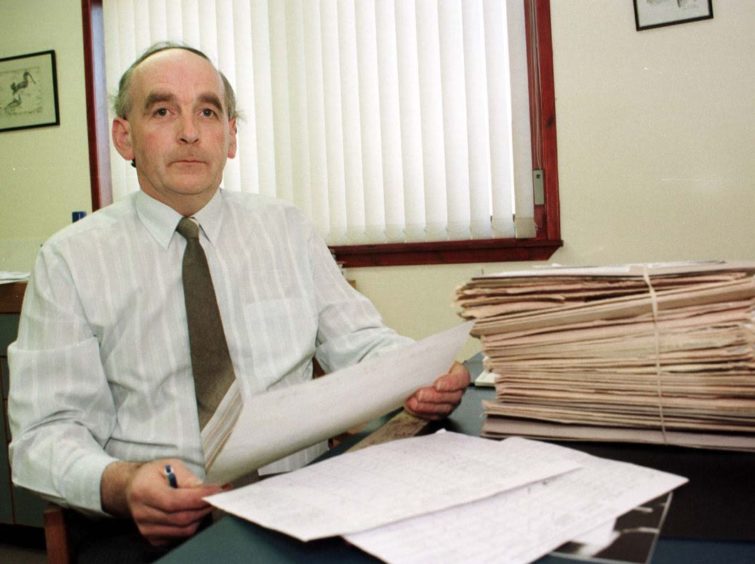

At the time, Det Insp Alan Smith, then head of the Grampian drugs squad, added: “You only get one crack at a man like Hamill. This man was very cute, his organisation was very tight.”

Ironically, it was one of Hamill’s few visits to the north-east that helped lead to his downfall.

Unaware he was being watched by police, he arrived in Aberdeen with what the force believed was the intention of attacking a man over a £30,000 debt. Unbeknown to Hamill, his intended target was already in custody.

Hamill broke into his flat only to find it empty, before returning a further three times to check if the man had returned.

Finally, in the early evening, he headed south in his Mercedes. Police noted he was joined by a Citroen containing a man and a heavily-pregnant woman.

When the couple arrived in Glasgow they spent the night in a hotel before heading back to Perth and taking the tourist route to Braemar. Police swooped and found £250,000 of heroin.

Now officers felt they had the evidence they needed and Grampian’s procurator fiscal agreed. It was time to arrest Hamill.

A team from Grampian Police travelled to Glasgow the night before the arrest, staying at a hotel.

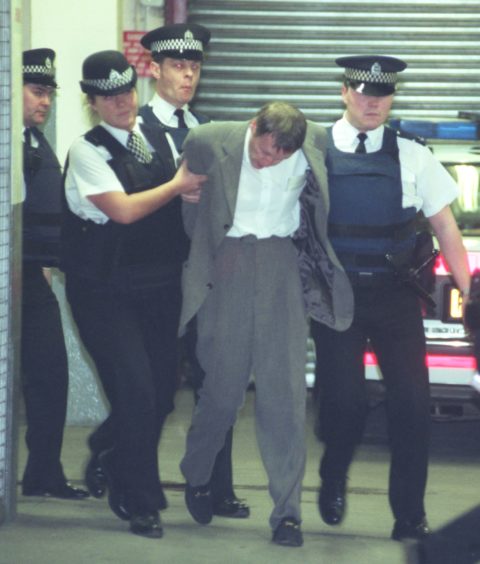

One former officer said: “On the morning of arrest there was the mother of all briefings. The atmosphere was electric. We’d been working towards this goal for years. We’d seen pictures of him, surveillance videos. We had intelligence he was heading to Manchester that day so he was taken out in a hard stop at a service station on the M74.

“We didn’t speak to him on the way back but he was convinced that the charges wouldn’t stick and that he’d be back on the streets after a week on remand.”

In February 1998, James Hamill and his gang appeared at the High Court in Aberdeen – the very city he had treated with such disdain.

Indeed, there were so many defendants the dock had to be extended. The gang were jailed for a total of 59 years, with the kingpin himself given an 18-year stretch behind bars. As many as eight dealers connected to Hamill and who sold drugs across the north-east were ultimately jailed as part of Operation Harvest.

After the case, DI Smith said of Hamill: “He was a pompous and arrogant individual who thought the world revolved around Glasgow. He held Aberdeen, the heroin-using population of Aberdeen, the judiciary and law system in contempt.

“He thought he was untouchable. He never believed anyone would speak out against him. Well they did.”

Part four: The end of the decade and a new danger emerges

While heroin was the drug that caused the most damage in the late 80s and early 90s in the north-east, officers were faced with a new menace that had the potential to wreak even more havoc. Crack cocaine.

Crack is a crystalised form of the powdered drug that came to prominence in the early to mid-80s in the United States where its use first reached epidemic levels in impoverished neighbourhoods in New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington DC, Los Angeles, and Miami.

The creation of the drug was born out of market forces – albeit of the criminal nature.

According to the US Drug Enforcement Agency, by the late 1970s there was a huge glut of cocaine powder being shipped into the United States. This caused the price of the drug to drop by as much as 80%. Faced with dropping prices for their illegal product, drug dealers converted the powder to “crack,” a solid form of cocaine that could be smoked.

Broken into small chunks, or “rocks,” this form of cocaine could be sold in smaller quantities, to more people at bigger profit. It was cheap, simple to produce, easy to use, and highly profitable for dealers.

Like most things American, it eventually made its way to the UK, first being used in the bigger cities such as London, Birmingham and Manchester. But, again, drug dealers are always looking for new and lucrative, markets.

Aberdeen, with its oil wealth, fitted the bill.

The arrival of crack

Detectives believe the drug found its way into the north-east thanks to prostitutes who often travelled to the area to make money from oil workers who had cash to burn.

One officer said: “Crack cocaine was mixed in with prostitutes coming up from down south, and taking seven-day lets in flats. Some of these girls were already crack addicts and introduced clients to the drug. In some cases, offshore workers from down south who maybe knew folk in the drugs scene down there would tell them there was money to be made in a soft market. It came from nowhere and just exploded.”

Officers were hugely concerned by the arrival of crack. They had heard and seen the stories from the States where it had devastated poor areas, sparking huge increases in violence and crime as gangs fought over the profits and addicts looked for cash.

The major issue with crack was that in comparison to other drugs the high lasted minutes as opposed to hours – but it was a powerful and addictive high.

Therefore, if you did the maths a user needed much more money to feed a crack habit than they did for heroin.

A retired officer said: “Where a heroin addict might spend £30-50 a day on heroin, a crack addict would need £200 a day to fund that habit.

“With heroin you’d have a high for a few hours and with crack it was 10 to 15 minutes. To fund that you either committed crime, shoplifting or break-ins, or dealt (the drug).”

Those using the prostitutes as couriers were Yardie gangsters. Originating from Jamaica, the term Yardie literally means “backyard” and is applied to Jamaican-born gangsters in the UK.

They were predominately based in London but after the Met’s Operation Trident, which targeted such criminals, many moved to areas like Birmingham and Manchester.

As profits rose they started to appear in the north-east.

“Aberdeen was a soft target. There were plenty of young guys making good money and no threat from incumbent gangs,” said the officer.

“These guys would come up from the West Midlands, set up safe houses, and keep moving around. Different faces, different cars, different phones. They never stayed in one place too long.”

Grampian Police took a slightly different approach with crack. They knew the problems it would bring if it took a firm grip – so they moved hard and fast.

Another retired officer said: “I guess we adopted a pretty aggressive stance on crack and had to step up our game. I suppose we were quite hard on it. We adopted the stance that we couldn’t wait to see how this would go.

“It was just attack at the first opportunity. We got quite good at building on intelligence that people were travelling up by train and then we’d take them out at the railway station.

“Let’s not pretend we got everyone … far from it. I suppose for every success we had there were another 10 we didn’t have success with.”

In one nine-month period police arrested 30 Jamaicans in Aberdeen. They were all illegally in the country and police suspected most of them were mules touring the country supplying crack to dealers in targeted cities.

One report said that at the start of the 2000s officers managed to identify six major criminals who were controlling Aberdeen’s crack trade. Two of them were based in London, and four from the West Midlands.

There was some intelligence to show the six made fleeting visits to Scotland, but the police did not have enough evidence to arrest them. At one point though the database of crack pushers operating on north-east streets grew to 243 names in just three years.

But as Aberdeen’s market was lucrative the city didn’t see the violence often experienced in other parts of the country. After all, there was plenty trade to go around. But that didn’t mean trouble wasn’t far away.

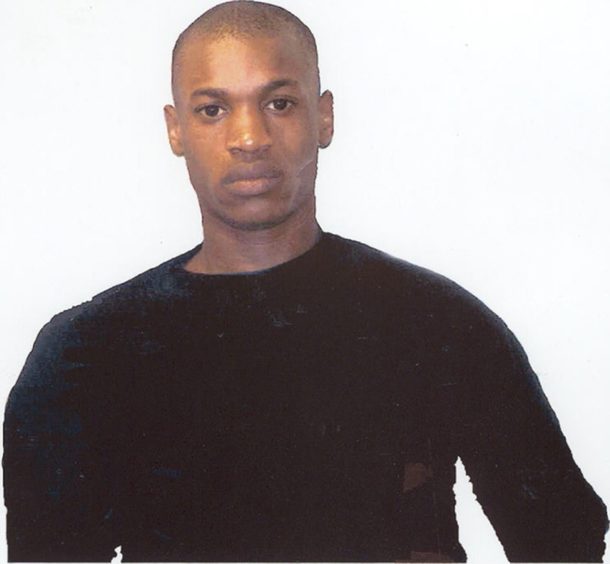

Kevin Nunes, a young man from the West Midlands, had started hanging around with a bad crowd — a gang of drug dealers linked to a notorious criminal gang in Heath Town, Wolverhampton.

He learned there was quite a bit of money to be made buying cheap cocaine in the West Midlands, then selling it on in Aberdeen.

In what was known as the “Aberdeen run”, small-time dealers would board a train in Wolverhampton and head up to the north-east, making three or four times as much as they could back at home.

Kevin, then 20, began making several trips. But his money-making scheme did not last long after he clashed with gang members back home.

Kevin’s bullet-ridden body was found on a grass verge near a farm in the Staffordshire village of Pattingham in September 2002 just 24 hours after he was released from custody in Aberdeen following his arrest over drugs.

Arrests were made and the suspects brought to court. The trial heard that the gang who killed Kevin was allegedly led by Adam Joof, 27, who was said to be making £40,000 a week from selling crack.

He was convicted of murder and told he would serve at least 28 years in jail. However, his conviction and that of other gang members was later overturned at the Court of Appeal in 2012. The court heard that concerns about the credibility of the key prosecution witness were not disclosed to the defence.

However, in 2019, police announced they were reopening the investigation into Nunes’s murder.

Part five: Even the quietest communities suffered

It’s a town that sits on the north-east’s wind-swept coastline, famed for its fishing industry and hard-working folk who put their lives at risk as they sail out to sea.

Fraserburgh is used to dealing with tragedy, having lost many of its sons to the icy grip of the North Sea through the centuries.

But in the 1990s, a new danger emerged in the form of heroin. It quickly became the drug of choice for many young people in the community, spreading in a fast and deadly wave.

The situation became so serious that Sandy Wisley, a GP in the town, famously said at the time: “If I threw a stone now, there’s a one-in-three chance I’d hit a junkie.”

Dr Wisley, who has since passed away, also published a study claiming there was an overdose in the town on average every 11 days in 1997 and 1998. Addicts would be revived, only to suffer another overdose at a later date. And there seemed to be no let-up in the problem as the 1990s went on. Indeed, there were more “emergency resuscitations” in the first quarter of 1998 than in the whole of 1997.

But for community stalwart Brian Topping – a man who has devoted his life to serving the community of the Buchan corner – Fraserburgh experienced the same problems – no worse or no better – as other north-east communities.

Mr Topping said: “I remember at the time, Dr Wisley was in all the Sunday papers. It was in the late 1980s or early 1990s. As a doctor he was treating and dealing with people who had a drug or alcohol addiction.

“A lot of folk were horrified by that comment (about throwing a stone and hitting a druggie). To me, Fraserburgh had been honest to say ‘We have a problem’ but it wasn’t as bad as that comment.”

A social stigma

While opinions may still differ even now, the impact of drugs was still clear in the community at that time.

There was, said Mr Topping, a tendency for folk to “cross to the other side of the road” rather than confront the scourge of drugs head-on. He said: “There was someone once in Watermill Road (in Fraserburgh) carried out in a black bag and folk said: ‘Look at that, that’s another druggie’. My first reaction would be ‘my heart goes out to the family.’

“Years ago, if you knew someone whose son or daughter or relative had drugs you tended to shy away from it. There was a social stigma. I was one of many people who wanted to do something about it.”

Smashing through that stigma was a challenge, but Mr Topping earned the trust of families in desperate need of help, due to his track record of assisting others in the area where he served as a local councillor for more than 30 years and where he still volunteers as a DJ, helping to raise money for good causes.

He added: “There’s quite a few people, not just in the Broch but out in the villages, who I’ve helped in one way or another with a drug issue when they were getting shunned by everybody.

“A lot of folk know me well. They could see that — here was a well-known person who was willing to put his head above the parapet.

“I remember in the 1980s I would get phone calls about fights out in the streets at 1am. My first thought is ‘Will you not phone the police?’.

“I would go down there at 1am. Once someone hit someone over the head with a spade and I went up to try to sort it out.

“Some folk said ‘You must be off your head’. I got things sorted out.”

Mr Topping saw first-hand the devastating impact of heroin in Fraserburgh.

“I remember (one case) where a boy was a bright, intelligent youngster, was in all the clubs and just got in with the wrong crowd.

“He ended up stealing things from the family home to sell to get money for drugs and his parents were heartbroken and ended up, like a lot of folk, putting him out of the house. They couldn’t take any more. The next thing is … he is taken out in a black body bag, with a life ruined.

“It’s always going to be in their mind every day when you’ve lost your son or daughter who had a bright future ahead of them. It made people realise there was a big issue, when one of their family members died of a drug overdose. It brought it home.

“Especially when it’s a younger person, it’s a tragedy for their family and friends. It’s a life that has been totally ruined.”

There were times when Mr Topping would turn Good Samaritan and risk his own personal safety, confronting drug addicts face-to-face about the turmoil they were causing in the area.

He described one tense stand-off with an addict who was causing problems for an elderly neighbour.

Mr Topping said: “It does put a strain on people who live next to or near people with drugs problems. For example, somebody may come looking for drugs and go to your door rather than the door they are supposed to go to and waking someone up at midnight or 1am.

“There was one house – a pensioner who lived upstairs said ‘I’m having trouble with this youngster downstairs’.

“He was in his late 20s. Folk were going out of the windows when police had busted (the house) a couple of times.

“I went to the house. I knew this person’s father. I said ‘I know your family is very concerned about you. I’ve got pensioners and families who live in this area (coming to me). Do you know if you get charged, you’ll lose your house? You’re causing a misery for folk. I want to try to help you.’

“He had been taking heroin. Folk said I was quite brave (to talk to him). We got help. He got counselling.

“This person now is a super guy with a family. Always got a smile and a wee ‘hello’. He’s probably forgotten all about it.”

According to Mr Topping, one of the reasons for the high number of emergency resuscitations was the trend for dealers to cut their drugs with other substances to bulk them out and increase the profit margin.

“People were taking stuff not knowing what is in it. It could be lethally strong, it could be diluted down with chalk dust and it could just kill you.”

Saving lives

The drug problem troubled Mr Topping so much in the 1990s, when he headed the former Grampian Regional Council public protection committee, that he cleared a whole week from his diary and headed on to the streets of the Broch on a fact-finding mission with the area’s deputy chief constable, David Garbutt, to see what they could do to save the lives of heroin addicts.

Mr Topping said: “We went to visit drug addicts and their parents so we could actually understand the issues they were going through.

“They were stealing things from their house and selling them off to fund their habit. Eventually (parents) were putting their son or daughter out of the house because they couldn’t put up with it anymore.

“We visited a couple of big companies. We saw what they were doing to combat it because safety was important: If you’ve got folk that perhaps are under the influence working machinery, you would not only cause a serious injury for themselves but for their colleague.

“We had a couple of parents who had family who had drugs issues. We set up a group and went to Fraserburgh Fishermen’s Mission. We had about 20 addicts there.”

Those who went along set up Clean-ex – a rehab group for addicts who wanted to stand loud and proud, named after a play-on-words from a famous tissue brand. Mr Topping encouraged members to show the world they were ready to change. One of their first activities was a stroll along Fraserburgh’s bronzed shorelines, armed with litter pickers and bin bags.

Mr Topping said: “I organised a beach clean. I said (to those taking part) ‘You’ve got to remember the way people feel about it’. “People will say ‘That’s a druggie, I’ll cross the road’. I told the (group members) ‘You need to try to prove to your families and the wider community you are trying to get on the road to recovery’.”

Another get-together for Clean-ex took place at the town’s annual celebration of the sterling work done by emergency services.

Mr Topping said: “The group had a table at Fraserburgh Blue Light Festival. They were next to a group of ladies who said ‘We’ve not heard of you’. They said ‘We’re actually recovering drug addicts, we’re trying to get back on the straight and narrow’. “The ladies were so impressed, they gave them some of their money towards the fishermen’s mission.”

As the years have rolled by, the townsfolk have changed their views about drug addiction as social stigma has worn off, said Mr Topping. The town too has built on its strong maritime heritage and is looking towards the future.

Mr Topping, who is chairman of Fraserburgh’s regeneration development trust, said: “There are lot of great and exciting things happening here to improve the image of the town and attract new businesses to the area.

“With money from the Scottish Government, Aberdeenshire Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund we have transformed a lot in the town, with more shops opening and many grants to help businesses improve their premises. There are still a lot more things in the pipeline.”

Part Six: The legacy

It was the telephone call every parent fears the most. The kind of call the mind conjures up in a nightmare that wakes you in the middle of the night in cold sweats, horrified.

A mother, who had spent most of her adult life caring for her son, hesitantly put the receiver to her ear and was told: “Come quick, your son is lying unconscious in the street”.

Panicking, Caroline Butler rushed to the scene in the Aberdeen suburb of Bridge of Don in a desperate attempt to save his life.

Those who had been socialising with her 28-year-old son Kevin the previous evening claimed he had suffered an asthma attack but her mother’s intuition told her his collapse was caused by something far more sinister.

When she arrived at the scene Caroline, now a retired NHS Grampian nurse, gave her son CPR but her efforts were in vain — and he died in her arms on Whitestripes Avenue.

That Kevin was to lose his life in 2001 was tragic enough – but what made it all the more difficult to take was he had been clean for months; the first time he had kicked heroin since he was 16.

Caroline, who now stays in Kittybrewster, said: “That was the worst part of it, but I’m convinced he took that dose of heroin intending to take his own life. Despite all the things he had accomplished for himself in the months beforehand and the hurdles he had overcome, he didn’t see a future for himself. He thought it was his time.”

Caroline said heroin was a “hidden beast” in Aberdeen in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“It wasn’t something people talked about, and it certainly wasn’t something you could go to a friend or relative and ask for help about if you were affected.

“Someone I know told me about a parent-support group that had started to meet at the Clerkseat Building at Royal Cornhill Hospital. I went along and walked in to see there were more than 100 people there, each with their own struggle.

“That was a clear sign that the problem was huge. It sounds strange saying this now, but attending that meeting gave me a good feeling because I no longer felt alone in facing this horrible problem.

“I felt as though I had failed at being a parent and, suddenly, here were all these other parents going through the same thing. It really helped.

“I said at that meeting that something had to be done to stop the issue of hard drugs getting out of hand. One of the doctors said at the time it was ‘just a phase’.”

Figures from the National Records of Scotland show 306 people died in Scotland due to drugs in 1980. In 1999, the figure was 492. The body only started compiling regional statistics in 1996, when 29 people died due to drugs in the Grampian area. The figure had risen to 38 by 1999 – and 25 of those deaths in that year were due to heroin.

It meant heroin was killing someone in the region every 15 days in the last year of the 20th century.

Each of those who lost their lives – and the devastated families they left behind – would have their own stories to tell about what led to their individual tragedies.

Kevin’s story

Kevin’s own story began with a firebomb.

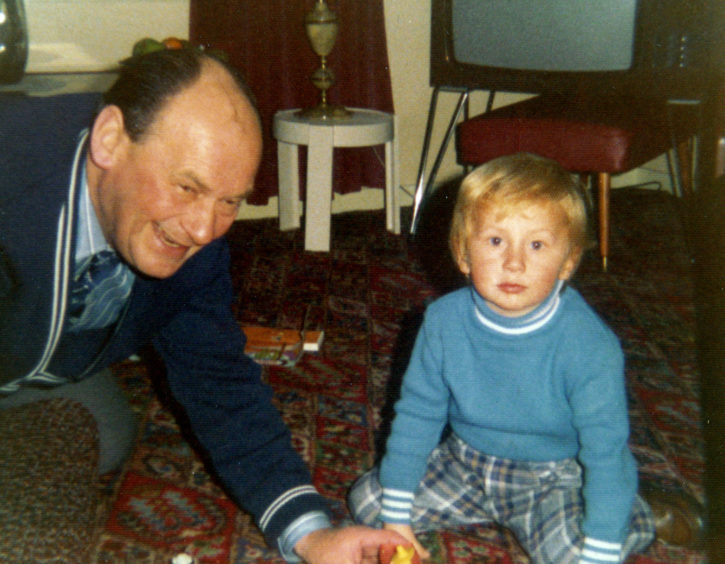

Kevin, aged 4, having fun with his granddad Benny Butler. As a child attending Kittybrewster Primary School, he was a bright and breezy boy – always smiling and tearing around, forever active and a bundle of energy.

Caroline said: “He was a fantastic football player. He loved football and so did his dad, but Kevin kept bad company as he got a bit older. He fell in with a bad crowd.”

Aged 14 and a student at Powis Academy, Kevin’s classmates were stirring up trouble with youngsters from a rival school and, as time went by, things got out of hand.

One night, the feud boiled over. A pitched battle broke out on a secluded field.

Caroline said: “School was very different then compared to what it is like today and, sadly, things like this would happen. On this particular day, two schools got together and had a fight. Kevin was involved in that. It got to the point where firebombs were thrown. The police were involved and the school felt as though they needed to take action.

“I was interviewed by a lady from social work and it was decided that Kevin be put in an assessment centre. That effectively meant he was excluded from school. I was absolutely devastated.

“It seemed unfair to me. Kevin had been involved but so had lots of others and they were making an example out of one person.”

Caroline, who was 41 at the time, added: “I was a young woman myself and was brought up to respect authority. This was the first time I’d ever known someone close to me getting into trouble.”

Kevin went into several assessment centres, all residential. It was an experience Caroline described as “horrendous”.

She said: “I saw him as often as I could, but they didn’t make me feel welcome.

“At one point, one of the members of staff told me it would be better if I didn’t visit often. I was appalled.

“I’m not sure why that was. I can only imagine it was because some of the children in there sadly did not have parents actively involved in their lives and so they were maybe worried about them feeling left out if they saw me with Kevin.”

A damaged individual

Caroline said she believes Kevin’s actions in later life were partly down to the “childhood trauma” he experienced in those assessment centres.

When he turned 16 in 1989, he left one of the centres and returned to the family home. But a chance discovery would change Caroline’s life forever.

“I was in his room and discovered a plastic bottle and a heap of tin foil. I couldn’t think what it was. People just didn’t know anything about hard drugs back then.

“One of my friends was a police officer’s wife and I asked her if she knew what it was used for. I was shocked when I found out it was for heroin.

“Kevin came out of the assessment centres with absolutely no skills whatsoever. He was a damaged individual – you could see that in his demeanour.”

Referring to her husband, who passed away in 2011, Caroline added: “Kenneth tried to get him a job at a printing firm and then at a carpentry company but nothing stuck. He didn’t have the work ethos that most people have. There was nothing saying in his head ‘I want to get up, go out and make something of myself’.

“At the same time, I wouldn’t give him any money, just so he could put a needle in his arm.”

Without any income, Kevin turned to crime to fund his habit, breaking into houses and stealing from shops throughout the last of his childhood years.

Caroline would often get visits from police officers after her son was caught breaking into houses.

She said: “I never allowed him to keep drugs in the house and he would just be out stealing to feed his habit. Police were constantly at the door.

“It frightened me to death – the thought he was breaking into people’s homes and taking their belongings.

“People often think that drug users come from deprived backgrounds but it wasn’t like that with Kevin. Our household went from a situation where having run-ins with authority was unheard of to the police being round all the time. Having something like this happen in the family was an alien concept.”

Caroline recalled the “heartbreaking” day police arrived at her Bridge of Don home with a search warrant.

She said: “They were searching the house from top to bottom. I told them ‘You won’t find any drugs’. Having them rifle through our things was quite humiliating, but I understand they have a job to do.

“It reached a point where my life revolved around Kevin. I would go to work as a nurse, finish my shift, come home and wonder at what point the police would come knocking.”

The procurator fiscal arranged for Kevin to see a psychologist about his pattern of offending and Caroline alleged the professional accused her of burying her head in the sand about his problems.

She said: “I felt everything was being taken out of my hands. Here was a boy, who became a young man, who was driven just by his need for heroin. How was I going to stop that? You can’t lock someone in the house round the clock.”

Kevin’s offending eventually caught up with him and he was sentenced to two years at Polmont Young Offenders Institution – a former borstal dating back to 1911, now designed to hold 760 inmates aged between 16 and 21.

Caroline would drive a 270-mile round trip every few days to visit her son and recalled an “atmosphere of tension”.

She remembered: “They are supposed to help rehabilitate offenders, but it never felt like that happened. The place had a particular atmosphere about it. There wasn’t much incentive for prisoners to engage with any help because drugs were being smuggled in for them.

“I remember one day going in to see him with a huge slice across his face. Somebody had attacked him with a weapon and you could see it had injured him badly. Seeing that was so hurtful for me – seeing that he had been hurt like that.

“He never would say what happened or what it was all about but I got the impression it was to do with taking somebody’s drugs and not being able to pay.”

Another custodial sentence was to follow, this time at Perth Prison – a 630-prisoner adult jail, which once boasted its own ‘execution shed’ that was demolished, having never been used due to the abolition of the Murder Act by the then Home Secretary Henry Brooke in 1964.

Kevin had been convicted of a series of housebreakings in the city trying to raise the cash for his daily heroin fix. He told police about a spate of crimes and was locked up for 18 months.

Caroline said: “His offending got worse when he came out of Perth Prison. I would say part of it was down to not coming off drugs while in prison and part of it meeting new people and learning new tricks of how to offend. He became more bold, which is the exact opposite of what you hope for as a mother, when you desperately want your son to get better.

“There was a change in his criminality. He would say to me he felt so worthless in himself and all he wanted to do was escape his mind.”

An entirely different person

One of Kevin’s most serious crimes came in 1994 when he went into a corner shop in Aberdeen’s Urquhart Road, armed with a knife. During a struggle, the then 22-year-old held the blade to the cashier’s face – an offence that led to him being jailed for six years at Shotts Prison in Lanarkshire – scene of mass rioting involving 100 prisoners just a year earlier.

The shop robbery still plays on Caroline’s mind to this day.

She said: “Kevin as a boy was a fantastic lad. Even through the worst of his offending, I don’t believe he was a nasty person. He cried on my shoulder and said sorry for putting that lady through that awful experience.

“I would have liked to have said to her (at the court case) – ‘I’m truly sorry for what happened to you. It was an awful, life-changing ordeal and it was wrong’ but I didn’t think it was appropriate to approach her.

“When you lose a person to heroin – they become an entirely different person.

“Kevin used to say to me ‘I will never see 30, mum. This is no life, this is an existence’.”

Then everything changed.

Entering his late 20s, Kevin resolved to turn his life around and got himself off heroin while approaching the end of his sentence in Shotts – where he served all of his six-year term.

Upon leaving custody, he enrolled on a methadone programme – using a controlled heroin substitute aimed at helping users regulate and kick their habit.

It worked.

Caroline said: “Kevin was like a new person when he came out of prison that time. It was evident that his whole demeanour had changed. He was confident having conversation.

“Kevin would ask ‘How is everyone in the family? How is granddad and grandma? It was good to see him like that. Heroin makes you incredibly self-centred because all you care about is that next hit. But here was Kevin taking an active interest in his loved ones for perhaps the first time since he was 15.

“I’ll never forget – he asked me ‘Will you come to see the GP with me?’ He seemed to have a goal in mind and wanted to make positive moves.

“He was put on a methadone script. A lot of people who move on to it never go off but he came off it completely. I can’t tell you how proud I was.”

As the world moved into the new century, the Butler family were looking forward to a brighter future.

One of Caroline’s fondest memories from that time was taking Kevin to visit her sister in Essex, southern England.

She said: “We had an absolutely wonderful time. I saw a side of Kevin I hadn’t seen since he was in school. My two nephews took him to an Arsenal (football) game. He loved it.

“I was proud of him because he didn’t try to hide his past. He was still on methadone at the time and would openly talk to people about it. He never shied away from it.”

Upon leaving custody, Kevin began to get intimate with a woman he had met through a mutual friend.

He would divide his time between the Bridge of Don family home and his partner’s home a five-minute drive away.

Caroline said: “She had a son. Kevin thought that little boy was the bee’s knees. He became the caring person that he would have been had he never got involved with hard drugs.

“He was so thoughtful towards his girlfriend and would always talk about her in a compassionate way. He knew she smoked heroin.

“One night he said to me ‘Do you mind if I go and see her and spend the night?’ I thought at the time there was no harm in it because he would be okay at her house, especially with her son around.”

Caroline’s trust was tragically misplaced. Rather than heading south-west across the River Don towards the Hilton area of Aberdeen to the home of Kevin’s partner, the couple stayed within Bridge of Don and visited a couple at a house near the Asda supermarket.

Kevin, his partner and the couple socialised that night – until Kevin’s partner made that phone call that every loved one fears.

Caroline said: “She sounded frantic. She told me Kevin had fallen unwell and had collapsed and was lying in the street. I was worried out of my skin.

“By the time I got there, his partner was sat next to Kevin’s body. They hadn’t phoned for an ambulance. She kept saying ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry.’

“They didn’t have Naloxone (a chemical used to revive people who have overdosed) back then so all I could do was give him CPR. I carried on and on but I knew my son was dead.

“The couple’s story was that he had an asthma attack.

“What I know from that night is that Kevin went up to a bedroom and shot up with heroin.

“My view is that Kevin did it deliberately. He had been clean for six months and would have known that going back to his regular dose after that long of a break would have overwhelmed his system.

“I believe he wanted to die. I don’t think he could cope with the world outside. This is what addiction is all about.”

Campaigning for change

Devastated by the loss of her son, Caroline wanted something positive to emerge from her trauma and so she volunteered with community organisation Substance Bereavement Support Aberdeen group.

Caroline said: “It was a lady called Wilma Falconer who started the group. Wilma has sadly passed away now. She was a brilliant lady – full of passion and empathy.

“It was really heart-warming to sit down and for someone to say ‘I know what it’s like. I know what you’ve been through.’ It gives you a well-supported feeling. It helped me considerably come to terms with what had happened to Kevin.”

Over the last 19 years, she has worked alongside other support groups such as Aberdeen-based Alcohol and Drugs Action and Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs and has been a source of support and comfort for recovering addicts and their families.

She has also campaigned for a change in the law.

Caroline said: “Childhood trauma and early-life experience is often the reason why people turn to drugs. I do not believe they should be treated as criminals. They should be supported and we need to look at the root causes.”

She has backed a campaign to decriminalise drugs possession and said she would welcome government-run injecting rooms in the North-east “with open arms” as they would become a safe haven for those affected by addiction.

Caroline said: “The question is not why the addiction but why the pain?

“I truly believe the stigma and reluctance to look at Kevin as a human being who is worthy of being helped was a barrier to his recovery.

“We have lost too many sons, daughters and other family members and I for one will always be advocating better facilities for those affected.”

If you would like to make a comment in response to this series, please email dale.haslam@ajl.co.uk to contact our reporter Dale Haslam.

If you have been affected by any of the themes explored in the articles, you can call a helpline set up by the Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs charity on 08080 101 011. Alternatively, visit sfad.org.uk to find out more about the charity.

Credits

Words and interviews by Richard Prest and Dale Haslam

Graphics by Gemma Day and Roddie Reid

Data visualisations by Lesley-Anne Kelly

SEO by Jamie Cameron

Story design by Cheryl Livingstone