To paint clear regional pictures of how cycling habits have changed before, during and after lockdown, the Press and Journal has analysed the results of the Pandemic Pedal Power survey by local authority area.

In addition, we have presented the comments and regional trends to each local authority and given them the opportunity to respond to our findings.

Here, we examine the results for Aberdeenshire – a sprawling rural area peppered with a number of sizeable towns and off-road trails catering to a variety of cyclists.

What’s happened?

In June, Aberdeenshire Council rolled out measures such as extended pavements and one-way traffic systems in the towns of Banchory, Ellon, Fraserburgh, Inverurie, Peterhead, Stonehaven and Turriff to both promote social distancing and encourage active travel.

The local authority is currently assessing how and when it may reduce or remove some of the changes altogether, depending on local Covid-19 infection rates. However, it has encountered some resistance to the changes among local residents and businesses.

What have you told us?

Aberdeenshire cyclists are most likely to own an average of two bikes, with dedicated road and mountain bikes the most popular choices. Shire residents are also the most likely to own “cyclocross” bicycles, designed to travel off-road as fast as possible.

As for why they cycle, cyclists from this area are most likely to do so for the health benefits, with less than 8% citing it as a convenient way to get around. Aberdeenshire is also the home of the hobby cyclist across north Scotland, with more people here saying they take part in cycling events than across the rest of the areas surveyed.

Cyclists from across the area are least likely to be concerned about dog walkers and pedestrians when out on their travels, and are among the strongest proponents for mandated helmet-wearing and insurance for pedal-pushers.

By and large, locals here feel cycling infrastructure and the funding for it is poor, and 91% say they have experienced “close pass” incidents – with 16% of those experiencing them every time they go out on their bike.

Quality of the roads is a common frustration, with dozens of readers saying potholes were a concern – as was the conduct of other road users.

Lucy Ritchie said: “Road surfaces are pretty bad in places, traffic is dangerous and (there is) zero cycling infrastructure. I have suffered verbal abuse and people using their cars as ‘weapons’ to teach me a lesson on numerous occasions, it’s not very pleasant.”

On infrastructure investment, many commented that they had seen no evidence of any money being spent on cycling provision where they live.

“It is far outstripped by spending on other road users and yet most journeys that people take are only a few miles – perfect for a bike,” wrote Chris Bugg. “It’s an afterthought rather than part of the plan.”

Much like other parts of the north of Scotland, the overall conclusion from local cyclists was that Aberdeenshire needs dedicated cycling infrastructure to put cyclists on a level footing with other road users.

Fiona Cruickshank summed up: “A direct route, properly separated from traffic would be amazing and, I believe, well used.”

Case study: A bike for all the family

Angie Fraser is easily recognised by her neighbours as “the woman with the bike” – and once people have seen her bike it’s easy to understand why.

Mum-of-two Angie is able to take her kids out and about with her thanks to her three-wheeled cargo bike, which has a covered wagon at the front where the front wheel would usually be.

Cargo bikes are common sights on the continent, where families and even postmen use them to move people and bulky objects, but they are a rare sight in the UK.

But with the reassurance of her Dutch husband’s cycling sensibilities to lean on, Angie took the leap and made the purchase. She says it’s one of the best decisions she’s ever made.

“I’ve had it for about a year and it’s great as I can take the kids to school – they love it,” she says.

“We can go to the beach in our wetsuits and then get back on the bike without worrying about getting seats dirty. If more families knew about them and thought about it I think they would use them.”

Given that it is wider at the front than an average bike – around 88cm (34.6in), according to the manufacturer – Angie finds that drivers tend to be more courteous around her than she initially expected. The bike is electric too, meaning hills are never a struggle.

What is a struggle, however, is finding direct routes to where she wants to go. She can access Peterhead using a combination of bike trails and quiet roads – but getting to Ellon via the main roads is out of the question. For journeys like that, she falls back on her electric car.

“People think you can’t use these bikes in Scotland but you can – with routes. The routes don’t need to be off-road – they just need to be safe. It would be lovely if there were more, then I’d feel more confident.”

However, she has been encouraged by the greater number of people cycling in lockdown – and hopes drivers’ attitudes, and the environment, will change for the better in the long term as a result.

She concludes: “When I’m taking the kids to school and people are all driving there with engines running around young children with developing lungs, you know that isn’t right.

“If we were all cycling we wouldn’t have that. I hope this is a watershed moment.”

What is the council saying?

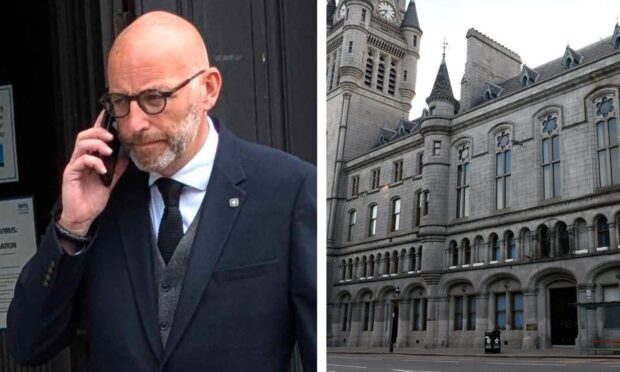

Aberdeenshire councillor Peter Argyle, chairman of the local authority’s infrastructure services committee, says the council would like to build more cycle lanes, but doesn’t have the money to do so.

Responding to the Press and Journal’s Pandemic Pedal Power survey, Mr Argyle acknowledged that the biggest barrier to getting people on their bikes is feeling safe but warned that segregated paths across the area for all were unlikely any time soon.

“As a country, the UK is lagging far behind and there are some real challenges,” he said.

“People really don’t feel safe on bikes which is where the biggest challenge lies

“Just the simple cost of putting in dedicated cycle lanes in Fraserburgh, for 500 metres, is £200,000. In a rural project for 800 metres, it’s £225,000.

“To put in dedicated lanes alongside the roads in an area with 3,000 miles of road? Without very significant change particularly in funding for local government that’s simply not an option.”

Despite this, Mr Argyle insists that active travel remains a “major priority” for Aberdeenshire, and acknowledges that the number of bikes passing his window each day has risen substantially during lockdown.

But with a £60 million budgetary shortfall to address this year and next as a result of Covid-19, cyclists will likely have to wait a little longer for their needs to be met – particularly because, he claims, the system that is used to decide annual lump payments to councils by Cosla and the Scottish Government does not serve rural councils properly.

“We need £20 million a year for school transport but the allocation is somewhere in the region of £3-4 million. In Glasgow it’s almost reversed. There is some great unfairness in the system.

“Without over-egging it the funding is clearly a huge issue when you talk about infrastructure.”

And while he concedes that not every road will have a cycle lane, he says lessons have been learned from the Spaces for People initiatives, such as the unexpected popularity of 20mph zones with town-dwellers.

Projects suspended by the coronavirus pandemic, such as a detailed design of a shared-use active travel path to link Marywell and Aberdeen’s Wellington Road corridor, are also still under consideration.

“I have no doubt at all there will be a huge change in how we do things to reflect the increased use of public transport and active travel. The signs are positive – there’s a growing awareness of the need for change.”