In these coronavirus-stricken circumstances, music can be a great release. Musicians are holding virtual sessions and online music tuition continues.

Another thing that the spread of Covid-19 has failed to halt is the hunt for relatives of a north-east piper, whose most famous composition is said to have been the inspiration for Bob Dylan’s `The Times They Are A-Changing’.

Dylan’s famous song has a particularly apposite title, given the uncertainty associated with these troubling times.

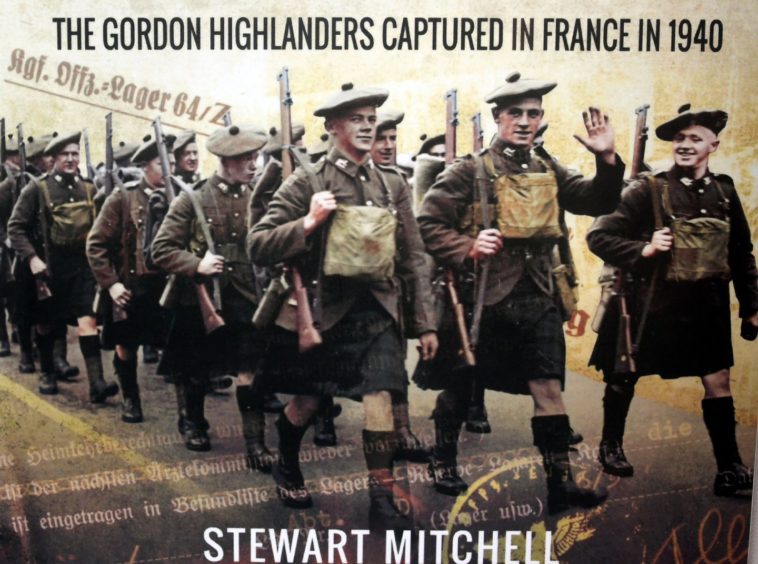

Less familiar than Dylan’s anti-establishment lyrics is the story behind its tune and the role played by James Robertson, a Pipe Major in the Gordon Highlanders who was familiar with a far more aggressive form of self-isolation than we are experiencing today.

It has been strongly suggested the song’s melody can be traced to a tune written by Robertson in 1915 when he was languishing in a Prisoner of War Camp having been captured by the Germans at Bertry, France.

Robertson, also known as Robbie, named his composition “Farewell to the Creeks” as he yearned for the inlets on the Banff/Portsoy coastline, where he was from.

He had good reason to be homesick. He wrote the tune in solitary confinement, having been banished there on account of his determination to make life difficult for his captors.

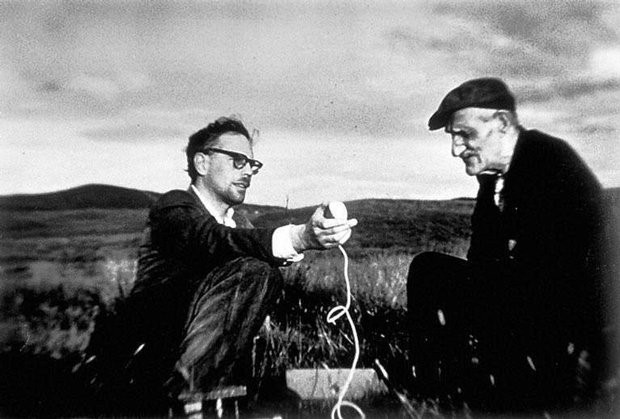

After the war, the tune became a great favourite pipers and pipe bands. Today a ground-breaking oral history project is trying to trace Robertson’s descendants to get permission to publish old tape recordings of conversations between the piper and the famous folklorist and poet Hamish Henderson.

Before the reel-to-reel recordings were made in the in 1950s, Henderson had played an important role in popularising Robertson’s composition. He took the tune and gave it memorable lyrics to fashion one of the great wartime songs

When Henderson was an intelligence officer in Sicily during the last War he was driven to the small town of Linguaglossa, where he heard the massed pipe band of 153 Brigade, made up of the Gordons and Black Watch.

“When they struck up again, the march turned out to be one of my favourite pipe tunes ‘Farewell to the Creeks’ composed during World War One by Pipe Major James Robertson of Banff,” Henderson recalled many years later.

“And while I listened to it, words began to form in my head – particularly one recurrent line ‘Puir bloody swaddies are weary’…..And they were too. I knew that shortly they were going home, presumably to take part in another D-Day in north-west Europe.”

Within moments Henderson had written the verses to the song, which was to become known as the Banks O’ Sicily (The 51st Highland Division’s Farewell to Sicily) and which begins: “The pipie is dozie, the pipie is fey, He winna come roon for his vino the day.”

Robert Wallace, a piper and journalist who runs the website Piping Press, knew Henderson before he passed away in 2002.

“Hamish had a wonderful way with language in that Robert Burns tradition. He turned a great pipe tune into one of the great anthems of the Second World War,” Wallace said. “The Banks O’ Sicily encapsulated how the soldiers felt, much more than the sort of kitsch and romantic stuff that came out of the conflict.”

Dylan enthusiasts and musicologists believe the singer/songwriter heard the ‘Banks O’Sicily’ on visits to the UK and lifted the tune for his song. They point to an interview in which the musician claimed it was influenced by an “old Scottish folk song”. Although Robertson’s composition is more modern than that, the similarities between the two melodies are striking.

Through his website, Wallace has made pleas for members of Robertson’s family to come forward so that the old recordings can be published for an oral history project Tobar an Duachais – Kist o Riches.

The project, which has already made available online several thousand hours of Gaelic and Scots recordings, is a collaboration between Sabhal Mor Ostaig, Edinburgh University’s School of Scottish Studies, the National Trust for Scotland and BBC Alba.

Project Director Floraidh Forrest has described the tapes, which were recorded in the Commercial Hotel, Turriff, as a “wonderful”. The piper describes how he came up with the tune in jail and reminisces about life in the north-east.

“These recordings bear testimony to an extraordinary man who had led a fascinating life and we would love to be able to share them with everyone,” Forrest added.

After leaving the Army, Robertson was the janitor at Banff Academy and a special constable. He taught many young pipers. Although renowned as a strict teacher, he inspired devotion from his pupils. He is remembered in the Gordon Highlanders pipe music collection as a man of “boundless humour and bonhomie”.

So far the search for his relatives has thrown up a distant cousin, but the project team hopes to come up with a more direct connection. The piper had a son, who was last heard of in Fochabers. But it is not known if he is still alive.

Anyone with information that might assist the project can get in touch with Fraser McRobert, at fm.smo@uhi.ac.uk, who is in charge of seeking permission for material to be published.

If successful, listening to a conversation between two great Scottish cultural figures about the genesis of a great American song would be a welcome distraction from the coronavirus.