As the country lumbers on with the restrictions of lockdown, brought about by the first global pandemic in more than a century, the nation seems to have navel gazed into its past as it searches for a chink of light at the end of the tunnel.

Blitz spirit, Keep Calm, Stay Home, Stay Safe evoke a rose-tinted view of our last great national crisis – notably one a good whack of the population didn’t experience – the Second World War.

Even the Queen sprinkled the soothing words of Vera Lynn in her speech to the nation, as the doors of industry closed and pub shutters pulled in March, promising “we’ll meet again”.

But, as with every crisis, there comes opportunity to try something new. As much happened in 1945, as the world emerged from the barbarism of its most deadly conflict.

Timing

The formation of the welfare state was borne on the back of two world wars, which themselves were interspersed with worldwide economic collapse, hyper-inflation, poverty and wage disparity.

It is, arguably, the largest shift in societal, political and economic policy in the democratic age, unmatched before or since.

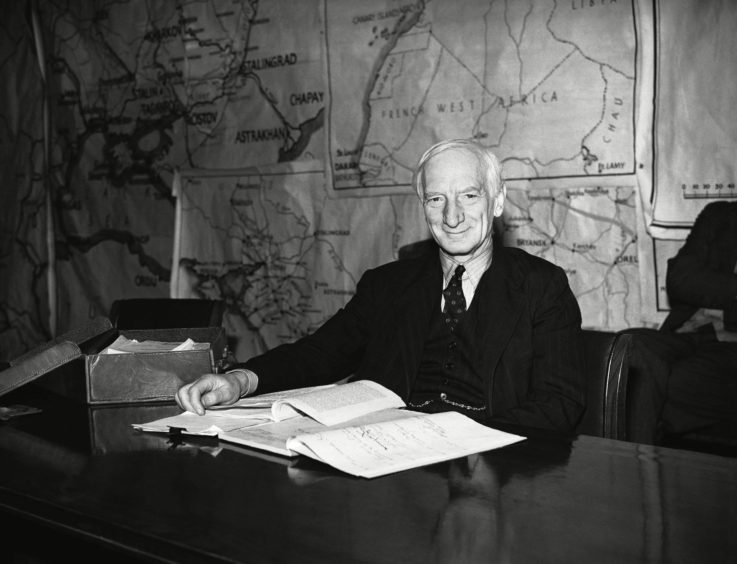

During the Second World War, William Beveridge published his report on the “five giants” which would need to be tackled as part of Britain’s post-war reconstruction – want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness.

As such, the NHS and the Welfare State were created, protecting British citizens from “cradle to grave”.

People suddenly went from having no cover, to protection from disease and ill-health, as well as an income if they became unemployed or unable to work.

The coronavirus pandemic has ground the country to a temporary halt, although economic activity has continued partially at a base level.

Expectation is economic measures like GDP will have crashed once we recover, physically, from the illness, meaning politicians and economists alike are suggesting ways to mitigate the worst on the labour market, stock market and globalised economies.

One such idea, which has been trialled in various countries, but as of writing never formally adopted on a national level, is the universal basic income.

Has the shutdown caused by Covid-19, a truly global pandemic, left as much a vacuum as the Second World War and is universal basic income the 21st Century’s answer to the welfare state?

AUDIO: Listen to the ‘New Normal’ series writers discuss their findings in this special Stooshie podcast

Dr Enkeleida Tahiraj, visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics, is a specialist in the policy and has advised the European Commission, the UN and the World Bank on economic policy.

She notes the upheavals caused by the coronavirus pandemic could act as “drivers” necessary to affect huge shifts in government policy, including the introduction of UBI.

“The catalyst for change in Beveridge’s time was the human and economic costs of two world wars, but also the need for a response to protests arising from the hardships of the inter-war years.

“This would suggest similar social dynamics and major shocks of a magnitude as the current pandemic is, might act as drivers for change in the policy landscape with UBI becoming realisable.

“It is difficult for us to appreciate the impact on people’s lives of the NHS and welfare state after its founding as it started from a different context. It seems unlikely that UBI would have quite the same impact, simply because we have known and relied on these public services.

“So it seems possible to consider that a UBI is more likely to be introduced rather like Universal Credit, albeit reaching everybody and without the problems that Universal Credit continues to have.”

What is universal basic income (UBI)?

At its simplest, universal basic income is a set payment for every citizen from the government, regardless of whether they are considered rich or poor.

Non-taxable, enshrined as a right in law and most importantly not means tested, everyone in the country would receive the base-line salary each month, guaranteeing “money in people’s pockets”, according to campaigners.

The Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland (CBIN) highlight five characteristics which define UBI:

- Periodic – it is paid at regular intervals (i.e monthly), not as a one-off grant.

- Cash payment – it is paid in an appropriate medium of exchange, allowing those

who receive it to decide what they spend it on. It is not, therefore, paid either in

kind (such as food or services) or in vouchers dedicated to a specific use. - Individual – it is paid on an individual basis and not, for instance, to households.

- Universal – it is paid to all, without means test.

- Unconditional – it is paid without a requirement to work or to demonstrate

willingness-to-work.

Think tank and UBI supporters Reform Scotland would want every adult to be paid £5,200 and child £2,600 per year – at a cost of £20 billion for Scotland and £235 billion for the UK treasury.

Proponents argue this could be offset by tax increases, elimination of certain benefits made redundant by basic income’s introduction.

But it is not just the (relatively short-term) cost to the public purse causing advocates to argue in favour of UBI.

Boost to the economy

Reform Scotland’s research director Alison Payne points out it is a method for the government to “put money in people’s pockets”.

If people have money, they in theory are more likely to spend it than not, which could be a quick-term “boost”, especially in local, smaller economies where “cash is king”.

Whether it would have a long-term impact on economic stimulus remains difficult to say, with Dr Tahiraj noting there have been some “extraordinary interventions” by governments worldwide, including the UK furlough scheme.

She said: “UBI could be a continuing stimulus to the economy. It is considered to offer greater cumulative and compounding social benefits over the medium to long-term.

“If introduced as a form of ‘emergency relief’ in a crisis such as the current pandemic, UBI could still offer individuals and households a meaningful level of income protection that would also have a positive stimulus impact when spent in to the economy in any form.

“We have recently witnessed some extraordinary interventions in response to the crisis domestically and abroad, mostly in the form of grants and loans which however is not actually stimulative at this point.

“We can’t jump to conclusions about such impacts of UBI but it is interesting to consider the potential impacts of UBI in the light of measures such as the furlough scheme.”

Social mobility

Unlike Universal Credit and other state benefits, a basic income would be the same in Lochee as it would in Knightsbridge.

Currently, the Living Wage in Scotland is £8.82 per hour, whereas in London it is £10.75 and as such benefits are adjusted for living costs, age or other means tested reasons.

Delivering UBI at different levels across the UK would be too expensive, Dr Tahiraj said, as well as being detrimental to social mobility.

“The case for a universal benefit level lies in its potential as an anti-poverty measure, as it offer greater purchasing power to those in less advantaged areas with lower price levels,” she adds.

“The argument for varying UBI levels is based on the idea it should reflect variations in the regional living costs.

“This rests on a somewhat erroneous conception of equity that anyway is countered by the increased administrative burden and costs of adding criteria checks.”

Freedom to choose

Alison Payne notes a basic income would give people the choice to take-up work in their chosen field, or take time to gain experience in another should they wish.

The “security” of a guaranteed cheque every month would mean people taking the leap into new roles or training programmes, knowing they would not face the risk of being sanctioned or having benefits withdrawn, she added.

“We hear stories of people having to turn down jobs which would give them experience in their chosen fields of work, because of how it would lessen their benefits and push them into poverty.

“With a basic income, this would not be the case.

“In future, it could mean people not working to live, but doing a job they enjoy and value.”

Dr Tahiraj highlights wider benefits at a societal level, allowing people to leave abusive relationships for example as well as arguing for better working terms and conditions.

She said: “With the security afforded by UBI, many people will be able to enter the labour market better equipped and prepared in terms of capital, as well as training and education, ultimately being able to consider a wider range of employment opportunities rather than falling into precarious and substandard contractual relations.

“That is likely to mean companies are required to respond by offering better employment standards, which some might consider undesirable.

“UBI’s potential benefits extend beyond participation in the labour market alone, as impacts have been noticed in regard to the freedom to exit abusive relationships, better health outcomes, household income pooling, among others.”

A disincentive to work?

Critics argue a universal basic income would be a “disincentive” for people entering the labour market.

Scottish Conservative MSP Murdo Fraser highlighted the old Scottish “tradition” of work being “fulfilling”, in his argument rallying against introducing UBI, adding: “I suspect that the great majority of Scots would be more inclined to the view that people should not receive money for nothing, particularly when that comes out of the taxes of those who are having to get out of their beds and work hard for a living.”

Dr Tahiraj points out that when the welfare state was forming in the post-war years, arguments against introducing the benefits system claimed people would stop working.

But, there still is the possibility introducing it could encourage some people not to engage with the labour market.

“We should recognise the possibility that UBI could act as a disincentive to participation in some instances,” she said.

“UBI’s role in the wider strategic and policy framework would need to anticipate this. So, implementation is key here – in terms of benefit level and coverage – as well as how UBI would be positioned regarding both welfare and fiscal policy.”

She added: “There is a tendency to subjectivise this issue and to script morality plays about the indolence of the poor, however the evidence points to this being largely a product of the inter-relationships between welfare and workfare.

“Many of the poor are already in the labour market on some basis and many of those who are not in formal employment do economically unrecognised work (as family members, friends, neighbours, community) that enables others to participate in the productive economy.

“My opinion is with UBI it is possible to create a virtuous circle, rather than the somewhat vicious circle that exists between welfare and work currently.

“Therefore the fear UBI would be a disincentive to people from participation in the labour market is misplaced, as if people would no longer want a better standards of living.

“It is not a pattern of human behaviour than when income is raised, one would lower expectations of the standard of living. Quite the contrary is true in fact.

She continued: “UBI appears more likely to encourage people to enter than to leave the labour market since it is unlikely to be set at a level that encourages people to leave the labour market, except for people who wish to radically revise down their consumption expectations.

“(Also) it has the potential to offer a springboard into the labour market, since the benefit should not be counted as taxable income, so people will not suffer a withdrawal rate as they earn more, unlike Universal Credit.”

The right or left thing to do?

The concept has its detractors, politically, on both the left and right. But a universal basic income, and calls to implement one, is more complex than the restrictions of typical political persuasions allow.

Scottish Conservatives fear it would be “cripplingly expensive” to introduce in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic and the Westminster government gave the suggestion short shrift when it was raised in April.

Internationally, the Communist Party of America claim it would lead to an increase in prices if the scheme was introduced there, as well as undermining union power.

Nicola Sturgeon said she had “long been” an advocate for universal basic income, adding the current crisis and disruption caused by the pandemic making the case for introducing it stronger.

She added the usual SNP caveat that tax raising powers to do so were reserved to Westminster, thus making it currently “impossible” for her to carry out her wish.

Finance secretary Kate Forbes added the Scottish Government would pursue introducing a basic income, not because of constitutional politics, but to ease future economic hardship in the event of new crises.

Prominent Lib Dem politicians have called for a basic income to be introduced, including Shetland MP Alastair Carmichael and Scottish leader Willie Rennie and the Scottish Greens have long-heralded the introduction of a citizen’s basic income.

Donald Cameron, the Scottish Conservative’s shadow finance secretary, said: “The idea of a universal basic income would be cripplingly expensive for the taxpayer at a time when it can least be afforded.

“Even the countries that have tried out this scheme seem to admit it’s not workable.

“In addition, this kind of wholesale benefits change would require a massive infrastructure upheaval at a time when the priority must be to rebuild our economy.

“It’s bewildering that the First Minister is talking seriously about this scheme right now, and suggests that she is losing sight of what is most important to Scots at this difficult time.”

Ultimately, as Dr Tahiraj points out, your support or not of UBI tends to be reflected on how you view public welfare more generally.

It would be down to the enacting government on how it was implemented, she adds, which means it could still vary from how it is argued for currently.

Hurdles

Ms Payne and Reform Scotland argue introducing UBI would not be just a case of putting money into people’s bank accounts, but a rewrite of the entire benefits and tax system in Scotland and the UK

“We don’t have the power in Scotland to do this. The power will have to either be devolved or basic income introduced on a UK-wide level,” she said.

“Introducing the basic income is more than just paying everyone a base-level wage, it would require a reconstruction of the entire benefits and tax framework.

“Currently, the Department of Work and Pensions and HMRC do not speak to each other, which makes the current benefit and tax system difficult.

“We have always called for the Scottish Parliament to be able to raise the money it spends, we have elements and levers which help how we support the Scottish economy but the full powers are not there.

“As part of the devolution settlement in Northern Ireland, Stormont has the ability to modify and control its benefit system – it so far has not chosen to and they do not have the ability to raise the money and if they did it would impact on the block grant.

“This could be remedied in Scotland by having full control on tax raising powers.”

The current Westminster government, however, is not convinced.

When the issue was last raised in parliament, Chancellor Rishi Sunak ruled out implementing it as a policy.

He said: “Our schemes benefit many many millions of people, particularly the self-employed scheme which will benefit over 3.5 million people who need it”.

“And indeed the new bounce back loans will also be available to those in self-employment for those with business accounts as well.”

How soon is now?

So has the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent shut-down strengthened the case for a universal basic income? And is it any closer to being introduced, given the support politicians in Scotland seem to be lending?

Dr Tahiraj is not convinced it will be put in place immediately after the virus is suppressed.

But a policy once deemed “unthinkable” is now in routine discussion across the UK political spectrum.

She said: “The crisis has added to the case for consideration of UBI, especially given the risk of another pandemic or a ‘black swan’ event.

“In the absence of another event…it might be expected institutions will continue with the conventional tools they have – perhaps with increasingly unconventional ways of application.

“At this point UBI seems not yet significantly nearer adoption in the short-to medium term at UK level, especially given misconceptions and mis-categorisations among policy makers about what actually constitutes a UBI.

“Recent debates on the controversy regarding an emergency targeted cash transfer scheme implemented in Spain highlight this.

“The devolved authorities are however, further ahead in their thinking. Governments will try to get back to ‘business as usual’, but there will be increasing interest now UBI, the policy proposal that was ‘unthinkable’ only few months ago, might have been shown to be possible, if not necessary.”