Scotland’s ambulance service is near breaking point, with crews forced to wait up to 24 hours to offload patients into rammed A&E departments and staff being asked to work up to 10 hours without breaks. But how did it get to this point?

In recent weeks, union leaders warned a small sprinkling of snow could see the whole service grind to a halt this winter.

Paramedics and technicians are said to be facing “the most extreme circumstances we’ve faced in over a decade – if not longer”.

The army, firefighters and even taxi drivers are being drafted in to help keep things afloat.

Police officers revealed they were already “routinely” taking patients to hospital.

Here, we look at how it began with hospital wards struggling under the weight of Covid-19 restrictions – then grew as historical frailties and underfunding left exhausted staff struggling to cope.

What are patients facing now?

Health Secretary Humza Yousaf drew anger from MSPs and the public when he suggested people should “think twice” before calling 999 to help the service recover.

Those comments were described as “reckless”, particularly in the wake of reports across the country of people being badly let down in their hour of need.

We’ve reported a horrifying series of examples in recent months.

An 88-year-old man from Montrose with dementia endured a 15-hour wait, despite fears he could be in a large amount of pain with a leg at a “strange angle” after being sent home from hospital following a partial hip replacement.

A woman had to call a neighbour to help rush her husband to hospital and save his life after he suffered a massive heart attack because there was no ambulance available to attend his Argyll home.

He was later taken by helicopter to Glasgow for treatment but only after a further wait because there was no no staff available to drive from the hospital door to the helipad.

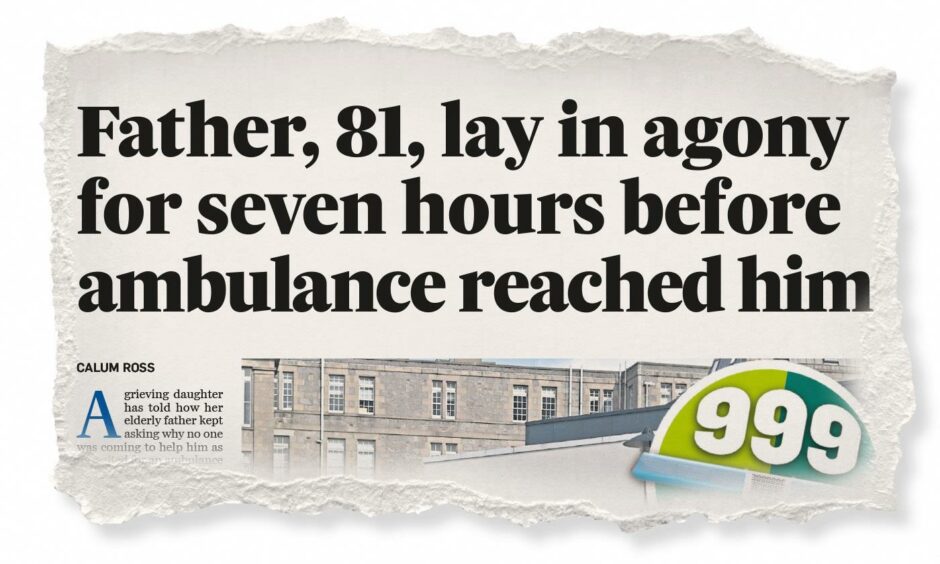

A grieving daughter told how her elderly father in Aberdeenshire kept asking why no one was coming to help him as he waited for an ambulance in “excruciating pain” for seven hours after he fell and broke his hip.

A Covid-positive pregnant woman from Moray was forced to wait more than five hours for an ambulance to take her on a four-minute journey from Aberdeen Royal Infirmary to the maternity hospital. It came after a four-hour wait to be transported from Elgin.

A businessman said a 13-hour wait for an Aberdeen ambulance to take his grieving mother to hospital only ended at 7am the following morning because he pleaded for help on Twitter.

Is this just a problem in Scotland?

Scotland is not alone in having to call in the army to help with its ailing ambulance service, with England and Wales also issuing calls for assistance, but a range of existing issues have also complicated things.

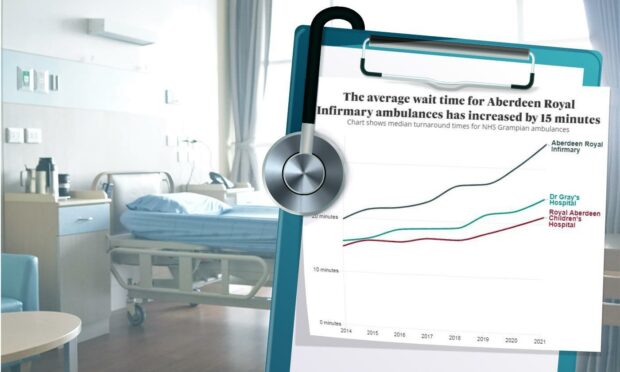

Figures on ambulance turnaround times obtained by us through Freedom of Information legislation reveal a worrying trend stretching back years.

Nicola Sturgeon said the NHS is dealing with “crisis conditions as a result of a global pandemic” and warned last month “this will be the hardest winter the NHS has faced in any of our memories”.

Earlier this week it emerged Scotland’s accident and emergency waiting times have hit their poorest level on record.

More people are turning up at A&E than at any other point during the pandemic and wards remain under tight Covid capacity restrictions.

On top of that, health bosses say patients are arriving in worse condition than previous years because of putting off treatments during the pandemic.

In August, NHS Grampian, NHS Highland and the Scottish Ambulance Service issued a joint statement detailing the continued struggle to cut down on A&E admissions and speed up ambulance response times.

Is Covid an excuse for deeper problems?

The ambulance service’s chief executive, Pauline Howie, said the easing of Covid restrictions is partly to blame for the increased demand.

She also blamed “lengthy hospital turnaround times”.

However, union leaders and patients have argued Covid is “no excuse” for the current situation. They believe longer-term frailties in the health service have been made worse by the pandemic.

Long-term ‘understaffing’ blamed

Jamie McNamee, Unite union convenor at the Scottish Ambulance Service with 35 years of experience, points to long-term understaffing issues, a shortage of acute beds, out of hours services and specialist medical practitioners.

He said the Covid has been used as a “convenient hat stand” for long-term problems hanging over the NHS.

Official figures from the Scottish Ambulance Service shows the overall staff count, taking in both paramedics and ambulance technicians, has increased year-on-year in every service area since at least 2017.

However, Mr McNamee believes these figures have fallen consistently below what is needed to run the service sustainably and has in the past been covered by ambulance staff working overtime during winter and other busy periods.

He warned that may not be possible this year because crews are already exhausted from tough working conditions and few breaks.

Further data from Public Health Scotland reveals how acute beds have been cut over the past decade, falling from 14,227 across Scotland to 12,869 in March this year.

Grampian – one of the worst affected health board areas for ambulance waiting times – saw the biggest drop off in the number of acute beds, at 27.5%, while there was an 18.5% fall in the NHS Highland area.

Tayside was also worse than the national average, seeing beds cut by 11.2% since 2011/12, with only Fife and Forth Valley seeing an increase – at 15.6% and 23.2%.

What is being done to help?

The health secretary announced last month that hundreds of firefighters, military personnel, students and taxi drivers would help out as part of a package of “decisive and unconventional action to save lives”.

It came after the first minister sent a request for help to the Ministry of Defence.

However, plans for Army drivers to take on emergency calls had to be scrapped after it emerged they do not have the correct licences to blue-light passengers to A&E.

Mr Yousaf told parliament more than 100 hundred military personnel will be deployed, including 88 drivers and 15 support staff, to help support ambulance workers.

Minutes later, the Ministry of Defence stepped in to confirm the real number is 225.

A further 111 workers are being asked to operate Mobile Testing Units in a re-run of last year, when the military supported sites at the height of the pandemic.

Mr Yousaf confirmed some firefighters will be redeployed to help drive ambulances in a bid to get a grip on the crisis, with taxis used in other cases to convey non-seriously ill patients who do not require emergency transport.

He said around 100 second year paramedic students will also be asked to help out in ambulance control rooms, while the number of hospital liaison officers at the busiest A&Es will be increased in a bid to admit patients more quickly.

What happens next?

Mr McNamee said the ambulance service is in a “massively worse” state than previous winters and warned the coming months are looking “bleak”.

Speaking about the outlook for this winter, he said: “I would imagine if we have a small sprinkling of snow, we won’t be far from grinding to a halt.”

David O’Connor, Unison’s Scottish regional organiser for ambulance staff, said workers are enduring “the most extreme circumstances we’ve faced in over a decade – if not longer” as they are asked to work up to 10 hours without breaks.

He pointed to an expected rise in flu cases, a return to nights out over the festive period, the continuing Covid-19 pandemic and existing winter pressures, such as staff sickness, on top of the waiting times crisis.

Opposition parties have called on the health secretary to come up with a plan, warning ambulance crews are now at “complete breaking point”.

What does the ambulance service say?

A Scottish Ambulance Service spokeswoman said staff are working “incredibly hard under sustained pressure” and their wellbeing remains the service’s top priority.

The spokeswoman said lengthy patient handover times continue to be a “major issue” but military personnel are providing additional capacity to assist with service pressure, particularly around lower acuity emergency and timed admissions calls.

She added: “Recruitment and training of new ambulance staff also continues across Scotland at pace to provide additional capacity going forward.”

What can the Scottish Government do?

A Scottish Government spokeswoman said the Covid-19 pandemic “has been the biggest shock the NHS has suffered in its 73-year existence and has heaped pressure on our ambulance service and wider NHS”.

“The health secretary recently set out £20 million of additional funding to help increase ambulance service capacity and improve response times and staff wellbeing,” she said.

“The ambulance service is also carrying out a national review of demand and capacity which will help to ensure they are working as efficiently as possible and have resources in place to meet both current and projected future demand.

“We are committed to supporting this work and recently announced a further £20 million in funding for the review.

“As part of this review, the service will see new ambulances introduced and almost 300 additional staff in place throughout the country. This will reduce the requirement for on-call working in some of our more rural communities.”