The cheese is out, the wine is poured, and if you’re not careful Christmas will soon resemble a lockdown weekday at Downing Street.

But as you go about your legally-endorsed family gatherings, what better time to take stock of a year like no other?

Well, maybe apart from the one before.

From Brexit, to an election you probably forgot even happened, and on to Boris Johnson’s “work meetings” with nibbles in a pandemic – there was enough in any given day to fill a normal year of rolling news.

Here’s what Scotland’s politicians were up to as we battled Covid and all the rest 2021 could throw at us.

Alex Salmond and a Nationalist split

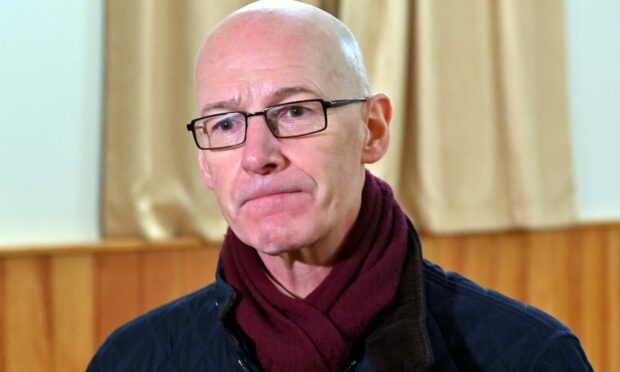

The start of the year saw the beginning of the end of the saga which was the fall-out between Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon.

Not one but two inquiries were launched into the government’s and First Minister’s behaviour on the handling of the complaints into Alex Salmond — who was acquitted of all charges of sexual assault at the High Court in Edinburgh in 2020.

It wasn’t pretty.

Salmond claimed there had been a a “deliberate, prolonged, malicious and concerted effort” by SNP chiefs and the Scottish Government to have him sent to prison.

Ms Sturgeon was eventually found not to have broken the ministerial code over her involvement in the fiasco, meaning she did not have to step down.

The government’s actions were branded “seriously flawed”.

Not confined to Salmond and Sturgeon, deputy first minister John Swinney was subjected to a no confidence vote off the back of the Salmond Inquiry.

Nearly forgotten at the end of it all, again, were the women who made the initial complaints.

The Scottish Government let them down with “serious flaws” and “catastrophic” decisions,

And out of all these ashes, Mr Salmond decided it was time to go for broke and show the mainstream SNP what it had become.

Did someone say “election time”?

All (some) change at the top

With all the excitement engulfing the SNP, it seemed Scottish Labour were meanwhile feeling left out so the party promptly defaulted to type and had another implosion.

Richard Leonard, the mild mannered union man at the helm of Holyrood’s third party, was replaced after another round of infighting.

Step forward Anas Sarwar.

The Conservatives had already done their own coup with Jackson Carlaw replaced by Douglas Ross, the refereeing MP who appeared hell bent on mopping up all the available jobs in Moray.

The Lib Dems kept ploughing on with the fearless Willie Rennie in the driving seat/cockpit/any other available photo-op.

And Greens leader Patrick Harvie kept up his job-share with Lorna Slater – more of whom later…

Super majority or bust

In the wings, Mr Salmond’s fledgling Alba party launched in predictable fashion.

He promised not to split the SNP vote and work with them to form a so-called “super majority” for independence.

His fellow Russia Today presenter George Galloway also decided to throw his hat in for Holyrood, under the All For Unity, pro-Union banner.

It was to the Conservatives what Alba was to the SNP – and neither of the two largest parties wanted anything to do with it.

Both new parties inevitably flopped, despite protestations from Mr Salmond that it was a success just to get registered in time.

Mr Galloway promptly forgot all about Scotland and contested the Batley and Spen by-election later that month. Which he lost.

The election itself did not exactly set the heather alight (thanks, Covid).

But it paved the way for another first for Holyrood – an SNP-Green government.

Just don’t call it a coalition.

Greens for go

Before you could say the word “principle” new ministers Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater found themselves in a tight spot over election promises including the creation of a nationalised energy company.

During the campaign, parties trod carefully and diligently checked opposition photo-ops to make sure the strict Covid rules were being adhered.

There were some rather large breaches, including local MSP and government minister Graeme Dey and deputy first minister John Swinney.

He posted several images to social media of a gathering after asking a group of SNP supporters to help “mark the first day of the Scottish election campaign”.

The gathering, which according to the pictures included at least eight people, some of whom appeared to have travelled from other local authority areas, breached restrictions because of the age and number of people that attended.

Also in Angus, Scottish Labour printed a leaflet on behalf of their candidate which offered to help people in Forfar — a town outside the constituency he was campaigning for.

Graeme McKenzie, the candidate for Angus South, had already apologised for a “clanger” that week after posting on social media he was leafleting in Forfar, which is in Angus North and the Mearns.

A party source suggested the leaflets had been “mistyped” and had intended to say “Forfarshire”, which has not been used as a constituency term since 1929.

John Swinney was also caught out, after he posted a picture on social media showing him meeting with four other party activists while out leafleting for May’s Scottish Parliament elections. He was then heavily criticised for “deleting the evidence”.

Election done, let’s save the world

Scotland surprised no one this summer by winning one point and scoring one goal at their first major football tournament in 22 years, but many feared the looming COP26 climate conference summit in November was setting the nation up for a bigger embarrassment.

With 2021 hindsight, COP26 went ahead smoothly. But the weeks leading up to the event were fraught with fears the whole experience could be a banana skin for everyone, from a refuse collectors to the first minister.

President Joe Biden, Greta Thunberg, Sir David Attenborough, Leonardo di Caprio and other dignitaries all descended on Glasgow, to varying degrees of welcome.

But before it could kick-off, Glasgow’s refuse workers threatened major industrial action, in a city already thought to be “in need of a clean”.

Not wishing to miss-out, the country’s train drivers also promised to strike, which would have ground the country and its public transport system to a halt — hardly a shining example of a green leader.

Probably most glaring was the economic and environmental cost of transporting massive, bio-diesel generators across the country to hotels and staying-places of the COP attendees, so they could charge their vast fleets of electric vehicles.

In the end, COP secretary Alok Sharma cried as he apologised for a “watered down” climate deal, before saying he was actually just tired. Aren’t we all.

The long-term impact will be keenly felt in our small corner of the globe.

Oil used to the basis of a Scottish economy – now mainstream politicians are considering how to turn off the taps.

Tory own goals

The oil policies might well be useful for Conservatives looking to hold on in the north-east, particularly.

But the party had a shocker across the UK as the year went on.

In December, the Conservatives lost a seat they had held for 200 (!) years in the North Shropshire by-election.

Triggered by the resignation of Owen Paterson, the Tories suffered a 34% swing to the Lib Dems, the highest turnover since the Major government in the early 90s.

Paterson resigned following a massive stooshie in parliament after an investigation by the Commissioner for Parliamentary Standards accused of breaking lobbying rules for MPs.

Rumours started flying that Boris Johnson wanted a change to the rules before his own “wallpapergate” investigation got underway.

MPs came under further scrutiny for their second jobs, including Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross, who “forgot” to include a number of registered interests and his earnings.

The way in which people were awarded peerages came under further investigation, including a new Scotland Office minister — who is also a failed Scottish Conservative candidate.

Businessman Malcolm Offord, who worked in financial services and donated money to the Tory party, was announced as a new junior minister at the Scotland Office in September. What luck.

A neverendum?

It might feel like several generations have passed since we were asked to vote on Scotland’s constitutional future, but it’s only been six years.

But in that time a lot has changed, not least Brexit.

As sure as the sun rises every day, Scotland’s political calendar was marked by constant calls for another vote – and constant arguments it is just too soon.

The election returned a pro-independence parliament, but the dial hasn’t shifted much either way over the year in public attitudes.

Ms Sturgeon still says she wants a referendum soon – so 2021 can go down as just the latest year where we were marched up the hill, and back down again.

Remembering David Amess

It was a rough year for party politics with constant bickering and point scoring on everything from global trade to never-ending culture wars.

The nonsense was abruptly put in sharp focus by the horrific killing of Conservative MP David Amess.

This senseless death was a wake up call at the scale of a national problem.

It’s also a reminder that, despite our light-hearted look at the trials and tribulations of UK and Scottish politics, this is an uncertain time.

The tensions of economic gloom, growing intolerance, a horrific global health crisis and bitter partisan splits, all conspired to create a sometimes toxic political atmosphere.

The Covid challenge for a new year

This was a year bookended by Delta and Omicron, and shot through by the ongoing global trauma of the Covid pandemic.

Named for the variants in the Coronavirus strain which ground the world to a halt in 2020, Delta put a stop to New Year celebrations in January.

The way things are shaping up, it looks as if Omicron is about to do the same for 2022.

Back in January 2021 we were in lockdown, unable to meet inside with pubs closed and restaurants shuttered.

The ray of light offered by the vaccine did not shine into view until later, meaning a cold, bleak winter period for many.

Schools were closed from the Christmas holidays until March and exams were again cancelled for secondary pupils.

It was not all doom and gloom, however.

Roll up your sleeves

The country’s beleaguered NHS — pushed to its limits by the first, second and third waves of Coronavirus and anticipating an overwhelming backlog of operations and non-Covid procedures — rolled up its sleeves, told us to do the same and set about making sure everyone who could get a vaccine did.

This monumental effort saw concert halls and live event venues taken over by hoards of doctors, nurses, medical staff, dentists and students as part of a collective show of community in the face of quite overwhelming odds.

The process was not always smooth, bad weather and kinks in planning saw some left out in the cold.

As of December, more than 80% of eligible adults had received their first dose, almost 4.5 million people.

Just short of four million have their second, and the booster programme saw a peak of 69,000 per-day before the year was out.

With that in mind, maybe 2021 also exposed the best of us too.

Hopefully, our review of 2022 will build on that as we all look forward to a happy new year.