Scotland’s political leaders were given a taste of future pandemic planning when an infected swan was found dead at a coastal village in 2006.

Newly released cabinet papers from Jack McConnell’s time as first minister reveal how avian flu sparked discussion of school closures, vaccinations and a future response to “panic or civil disobedience”.

The Labour leader said it had been handled professionally once the threat had passed.

But in the cabinet room, environment minister Ross Finnie complained the potentially lethal outbreak had been blown up into a “disproportionate sense of crisis” by some media reporting.

More than a decade on, the Scottish Government was trying to draw on the same flu-based lessons – and facing serious accusations there was a lack of preparation for what the world now knows as the Covid-19 pandemic.

When bird flu landed in the East Neuk

At the start of 2006, public health experts were “closely monitoring developments” of the spread of bird flu and deaths linked to infections in south-east Asia.

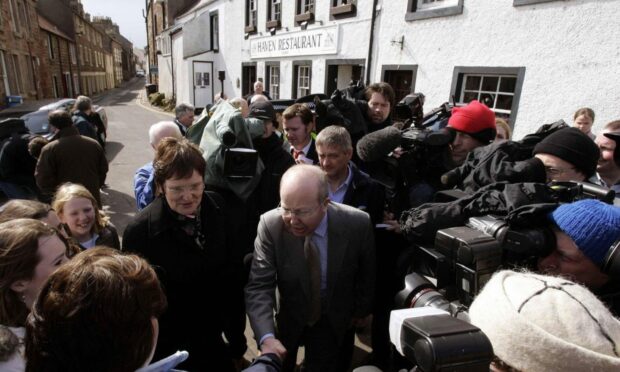

In March that year, a dead swan was found in Cellardyke, Fife.

The swan tested positive for the deadly H5N1 strain of bird flu, prompting the Scottish Executive to introduce an initial 1.8 mile protection zone around the village, further surrounded by a six-mile surveillance zone.

It was the first recorded case of the disease in a wild bird in Britain and it generated headlines across the world.

By 2008, a the World Health Organisation believed 385 people around the world had been infected with H5N1 and 243 of them had died.

Cabinet papers made available under the 15-year rule show that ministers met on April 19, 2006, one day before restrictions were eased in Scotland.

Mr McConnell told his colleagues he was “very impressed by the professional handling of the situation”.

‘Considerable overreaction’

Ross Finnie, a Lib Dem MSP for the West of Scotland, was environment minister at the time.

The minute said: “Mr Finnie said there had been a considerable overreaction to the incident on the part of the media.”

It added: “It was noted that this had been a useful opportunity to test existing procedures and the lessons learned from this would be drawn on in the future.

“It was also noted that the media had generated a disproportionate sense of crisis and succeeded in frustrating the communication of some key messages.

“It was agreed that the MGCC’s (ministerial group on civil contingencies) future thinking should encompass strategies for responding to the potential of the media to generate panic or civil disobedience.”

On schools, the papers state: “Ministers will propose the potential widespread closure of schools and group childcare settings during a pandemic as scientific modelling suggest that this might reduce illness in children by up to 50% and save lives.”

It added: “Few, if any, factors are likely to make it tolerable to knowingly expose children to avoidable, serious risk.”

Were lessons learned?

Th2 2006 papers show parallels to the response to the coronavirus crisis.

They include a push for those deemed most at risk – in that case, poultry workers – to be given an annual vaccination against flu.

The cabinet minutes from February state that the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation recommended vaccinations “to minimise the theoretical public health risk of avian flu mixing with seasonal flu and possibly mutating into a pandemic flu strain”.

At the start of the 2020 Covid pandemic, questions were raised about how far that planning had actually gone.

Three major exercises had been carried out – each finding problems with preparations.

Operation Isis reported “unease” over the availability of protective clothing, operation Silver Swan found gaps in social care and Exercise Sygnus highlighted problems with UK-wide preparedness for an outbreak.

By February 2021, independent public spending watchdog Audit Scotland had published a report identifying missed opportunities including availability of vital protective clothing.

How a fallen Holyrood roof beam raised concern

It was not the only time that year Scotland’s preparedness for emergencies had been under scrutiny.

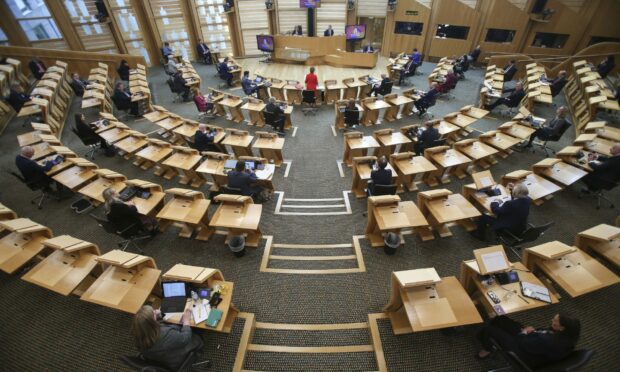

Arrangements for dealing with a pandemic were touched upon by the Cabinet a month earlier when a roof beam at Holyrood led to the evacuation of the chamber – a major embarrassment after the over-budget building was finally opened.

Ministers became frustrated at the handling of temporary accommodation measures elsewhere in a committee room.

The room could only accommodate 90 people and the decision was announced before it had been agreed by the parliamentary bureau.

A note of the Cabinet meeting said: “The way in which this issue had been handled by the SPCB (Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body) raised wider questions about its preparedness to deal with major civil contingencies such as a flu pandemic or terrorist attack.”

Ministers said the episode had “damaged the reputation of the parliament at home and abroad”, and that “public perception of the executive was also being damaged”.