The top social worker in Aberdeen says officials “missed opportunities” to prevent historic abuse of children in foster care.

Chief social work officer Graeme Simpson admitted it had been “painful” to hear harrowing evidence given by multiple victims to the long-running Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry.

In Edinburgh on Wednesday, he said “fostering has changed” but there is “learning” is still required.

One area that could be looked at is automatic case reviews after a carer has been convicted of an offence, even if they no longer look after children.

I found it difficult and at times painful reading … and it’s one of immense sadness.

– Chief social worker Graeme Simpson.

Mr Simpson said there was “merit” in considering such a move, after he was questioned on the case of Sheila Davies, who was found guilty of six charges in 2018.

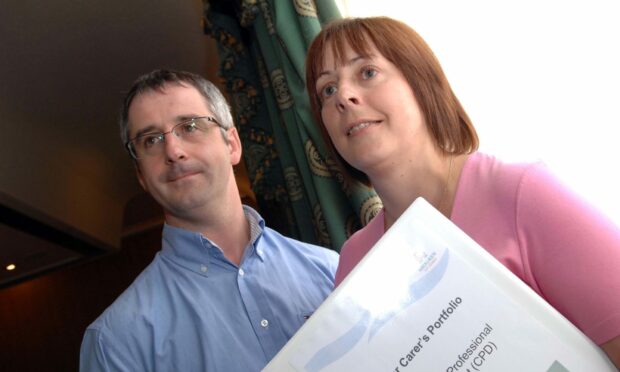

The city council manager was appearing before the inquiry, chaired by Lady Smith, for a second time during the current phase of its probe, which is looking into the abuse of children in foster care.

He was asked to comment on the evidence of multiple victims dating from the 1960s to the 1990s, although much of it related to cases from before he was involved in the service.

Themes included social workers ignoring clear signs of abuse, failing to carry out proper assessments and overcrowding of city foster homes.

Mr Simpson said: “I think I had reflections on all of the evidence witnesses have given.

‘Immense sadness’

“I found it difficult and at times painful reading … and it’s one of immense sadness.

“For me it does reflect that fostering has changed.”

The inquiry previously heard from the victims of William Watson, who was jailed for six years in 2013 for offences relating to two young girls.

He had denied rape and lewd, indecent and libidinous behaviour in Fort William, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire.

But a jury found him guilty of four charges of lewd, indecent and libidinous behaviour towards the children.

Mr Simpson said that if it had been today, Mr Watson’s suitability to continue fostering children would have been reassessed following the death of his wife in 1968.

Asked about a failure to act on reports to social work about Mr Watson’s behaviour, including regularly going out at night, Mr Simpson said: “There’s a missed opportunity there.”

He added: “That would not be what you would expect at all. There should have been further inquiry.”

The hearing has also been told about the case of two sisters who were sent to live in rural Aberdeenshire and were forced to work on a farm at a young age.

‘Almost Dickensian’

Mr Simpson described the circumstances as “almost Dickensian”.

One of the girls, known as “Janet”, had an accident on a piece of machinery, but social work staff failed to intervene.

Lady Smith said: “Nobody seems to have asked the question: what on Earth these girls were doing ‘playing’ on a piece of dangerous farm machinery?”

In evidence relating to another north-east foster carer, a social worker concluded there was “nothing to be gained” by asking questions about bruising and marks on the neck of one girl.

Mr Simpson said: “My reflections are that we didn’t investigate the bruises on the girl’s neck at all.

“No indication of police involvement. No indication indication of medical exam.

“Bruises on the neck are very worrying indeed. It’s a really serious place for bruising to be and causes significant concern.”

Bruising and “grip marks” were also reported in 1980 to social workers in the case of another girl, known as “Sarah”.

But the officials dismissed the concerns, and made remarks condoning physical punishment of the youngster.

Mr Simpson said: “For me, we haven’t been curious. We haven’t been putting the child’s needs at the forefront of our investigations.

“There was no professional curiosity. No concern for the child. Really not acceptable.”

Overcrowding

Overcrowding was another feature to emerge in the evidence, with one case involving an Aberdeen carer who had looked after more than 300 children, and another in which five youngsters shared one room.

Mr Simpson said it appeared like the policy was “any bed in a storm”.

He added: “These are not foster homes, they are almost children’s homes.

“We haven’t served these children well.”

The inquiry discussed Ms Davies, who was found guilty of attacking six youngsters aged between four and 12 between June 1993 and September 2001, at an address on Stornoway Crescent in Aberdeen.

Mr Simpson admitted there was a “cumulation of concerns” about Ms Davies in the 1990s, including the care she provided to older children, her ability to cope and the lack of money being spent on the youngsters.

However, she continued to foster children until she resigned in 2003.

Mr Simpson said: “There is always learning. I feel there is still learning that we as an organisation would want to consider and take on board.”

The top official also admitted that council staff changes and absences may have played a part in some of the failures.

“I have been left questioning to what extent a lack of leadership in the department left us not able to be as attuned to the circumstances as we should have been,” he said.

Conversation