The announcement by Douglas Ross that he will stand down as Scottish Conservative leader after July 4 falls into the “shock, but not a surprise” category.

The shock is in the timing. In truth, his colleagues expected him to quit – but only after election day, and assuming he won the Westminster seat for which he is standing. To say they are nonplussed by his declaration, in the middle of a fraught campaign, is an understatement.

There will be suspicion on two fronts. First, that the treatment of the popular David Duguid – the sitting MP who was blocked from standing as candidate for the Aberdeenshire North and Moray East constituency, with Ross then stepping in to replace him – has created an internal backlash that forced the timing of the announcement.

Second, Ross’s political opponents will point to new allegations that he used Westminster expenses to cover travel costs for his other job as an assistant football referee. Given the Scottish Tory leader’s key role in unseating Humza Yousaf as first minister, and his attacks during the Michael Matheson expenses scandal, the claims – whether they have any foundation or not – will be rolled out regularly in the coming weeks. Ross will be accused of running away.

There is concern, too, about the impact all this will have on the party’s election performance. The Tories are heading for a heavy defeat at Westminster, but the Scottish party was expected to perform relatively well, perhaps keeping all of the six seats it currently holds.

Insiders are worried about how the resignation will play. “We were on course to hold all we had before all this broke,” one told me. “He should have kept going until the election. Douglas was warned against it, but wouldn’t listen. Poor. Really poor.”

With the leadership suddenly up for grabs, there will unavoidably be manoeuvring during the rest of the campaign. MSPs such as Meghan Gallacher, the current deputy leader, and Russell Findlay, the impressive justice spokesperson, are being talked about as possible successors. It cannot help but be a distraction.

Whatever happens to Ross now, his successor will inherit a fiendishly difficult task. Indeed, the party’s general election thumping will only be the beginning of their problems.

It seems likely that a large majority among the rump of UK Tory MPs to survive the coming of Keir Starmer will be on the right of the party. The leader who replaces the hapless Rishi Sunak is almost certain to come from that wing, too. From this, many consequences will flow.

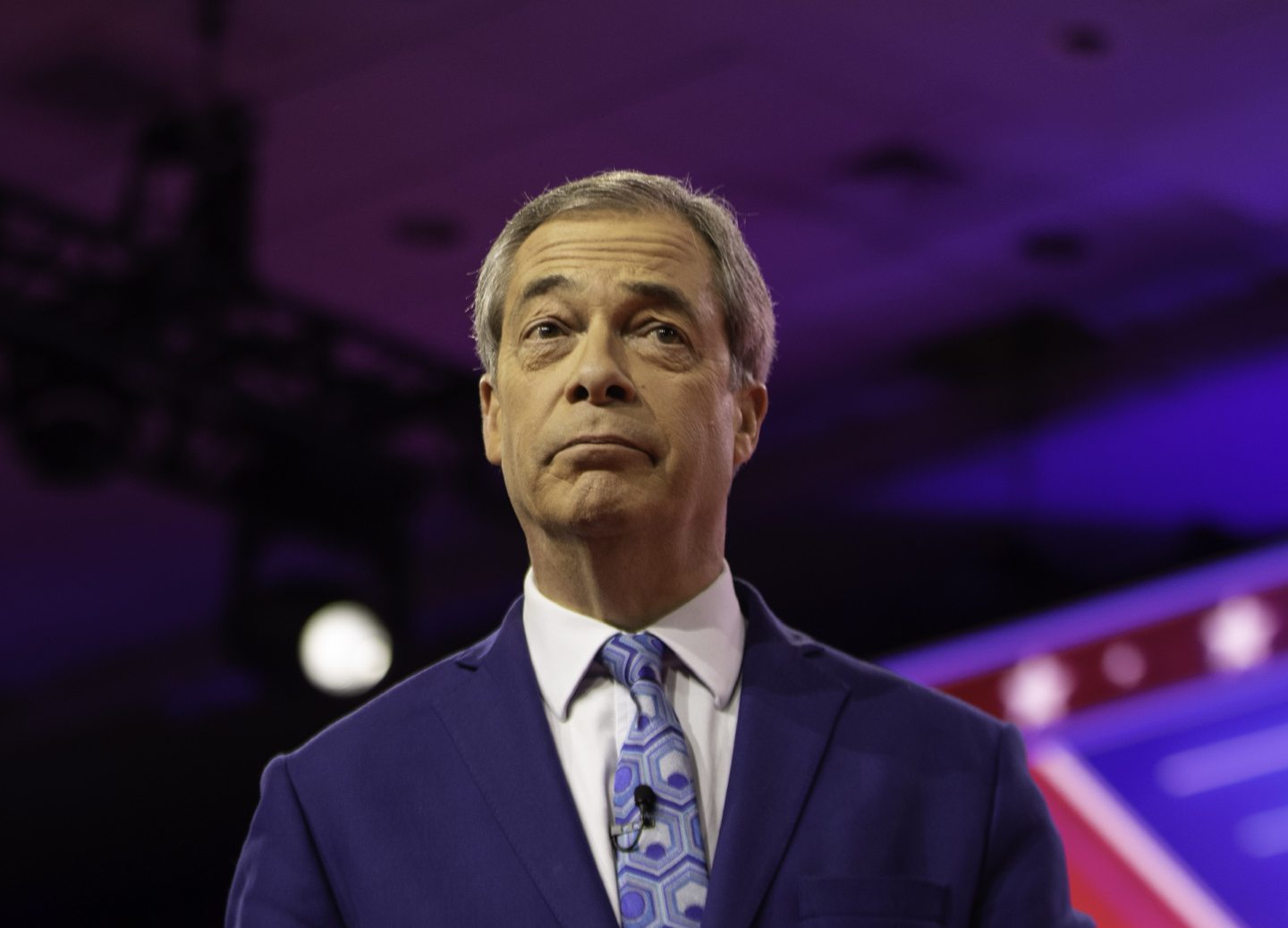

There is every chance that Nigel Farage will finally, at the eighth time of asking, be elected as the member for Clacton, the Essex constituency he is contesting as Reform’s candidate. There are already senior Conservatives arguing that, in the event of his election, he should be absorbed into their depleted party, and perhaps at an elevated level.

If you think Farage has been effective as a political outsider – and, like him or not, he has been one of the most impactful and disruptive influences in recent decades – just imagine the weight he would carry as an official representative of the old, venerable Conservatives. Such a platform would risk legitimising views that have often seemed extreme and even dangerous while spouted from the sidelines.

The era of Farage might be about to get underway

Under a sympathetic Tory leader, the era of Farage might just be about to get properly underway – especially if, as looks highly possible, his grisly ally and friend Donald Trump is re-elected US president in November.

Indeed, the party has been a plaything of the right since Boris Johnson ejected from parliament most of those moderate MPs who disagreed with his skinhead “deal or no deal” approach to securing Brexit. It has been obsessed with stamping down on immigration (though it has failed), how a Britain free from EU shackles can swashbuckle its way into being a global free-trading power (also a failure), and finding the right person to lead us into this future (various trials, all errors).

The success, such as it is, of the party in Scotland has been to stand as separately as it can from all this – it has sought to maintain a centrist One Nation brand of Conservatism.

In a Scotland that overwhelmingly rejected the governments of Margaret Thatcher, and which hardly warmed to Johnson or Liz Truss, it has had little choice. Ruth Davidson was perhaps the apogee of this liberal, inclusive approach. And, coupled with a strident unionism, she used it to take her party into second place at Holyrood, above Labour.

This was all just about possible while sheltering under the UK Conservative umbrella. What happens if the Westminster party now veers significantly right, especially with a devolved election due in 2026?

The new leader of the Scottish Tories, whoever they are, is being dealt a poor, poor hand

The prospect of Douglas Ross’s successor having to get to their feet in the Holyrood chamber to defend whatever extreme policies might be pursued by the new London leadership – even if that leadership is only on the opposition benches – is enough to send a chill down the spines of the candidates.

Imagine defending the appointment of Nigel Farage as, say, shadow home secretary, in charge of immigration and law-and-order policy. Or even just the return of Priti Patel or Suella Braverman to the front bench.

The new leader of the Scottish Tories, whoever they are, is being dealt a poor, poor hand.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation