It was hard not to despair watching the morning political programmes and reading newspaper columns on Sunday.

The adrenaline of the election a distant memory, it slowly dawned that Thursday’s poll was nothing more than another battle in the great war for the future of the Union.

Nicola Sturgeon’s triumph, of course, confirmed her dominance of Scottish politics but her failure to make that decisive breakthrough with an overall majority doomed us to a constitutional back and forth over who has the biggest mandate for years to come.

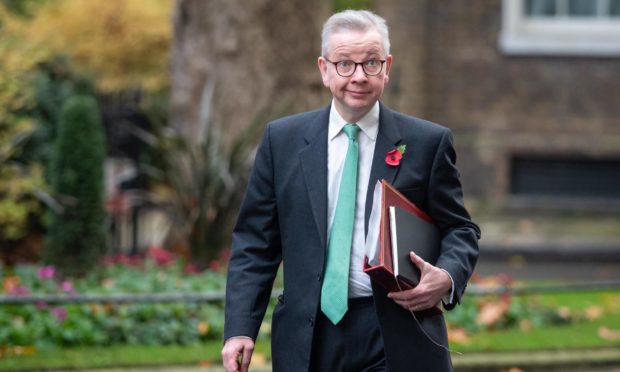

Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove was first out of the blocks with an argument that will no doubt be repeated ad nauseam by his colleagues in every interview where indyref2 features.

Mr Gove advanced that “a majority of people who voted in the constituencies voted for parties that were opposed to a referendum” and that Ms Sturgeon “didn’t secure a majority as Alex Salmond did in 2011”.

The first minister has been unequivocal in her response and has insisted her demand for another referendum on independence is now a “fundamental democratic principle”.

Both sides are agreed for now that the pandemic should take precedence, but don’t imagine for one second that there will be any kind of truce.

Fractious referendum

Battles and skirmishes will continue in Holyrood and Westminster, with the SNP certain to depict Boris Johnson and the unionist parties as “democracy deniers” frustrating the will of the Scottish people.

Number 10 will hammer home that the focus needs to be on the Covid-19 recovery and that now is not the time for a fractious referendum.

Tory apparatchiks will point to Ms Sturgeon’s own remarks during the election campaign, where she stated categorically “if you vote for the SNP you are not voting for independence, you are not even voting for another independence referendum”.

That is all well and good for the short term, but what happens when the first minister decides – possibly as soon as next year – to put in a request for a section 30 order?

The SNP believes that the UK Government’s refusal to even countenance circumstances in which a referendum could be held will make it seem the unreasonable party and will make it clear the Union is not based on consent. That is why many in Westminster are imploring the Downing Street machine to change tack.

Former Scottish Tory MP Luke Graham, who previously ran the Union policy unit in Number 10, warned on the weekend the next few years would be a “slog” for unionists and urged his colleagues to adopt the same approach in Scotland as they have to former “red wall” seats in the North of England.

Mr Graham pointed to the success of Ben Houchen, the Tory Tees Valley mayor, as a model for dealing with the SNP.

Houchen won the mayoralty in 2017 with just over 51% of the vote and on Friday he won with more than 72% of the vote in a region that could never be described as an enthusiastic Tory heartland.

The win was achieved with a bombardment of investment and ministerial attention from Westminster. Carbon-capture projects, private investment, the Teesside airport and a freeport were all announced far in advance of the election.

In addition, most of the Cabinet have visited, with headline-grabbing policies showing the value of delivery.

Such a strategy for Scotland is already in the works, with the controversial UK Internal Market Act enabling Westminster to spend in areas that were previously the exclusive remit of Holyrood.

Talk of road improvements, rail upgrades and investment in green industries has been welcomed, but it remains to be seen whether Union flag-clad infrastructure projects make any difference to the debate – especially given the fact many Scottish voters credited Ms Sturgeon for the UK Government furlough scheme that supported almost a million Scots workers over the course of the past year.

There is also a risk circumventing the devolved settlement through the UK Internal Market Act could end up strengthening the SNP’s hand, with accusations of a Westminster power grab becoming as effective as the Brexit “take back control” message.

Ultimately, it looks as though Mr Johnson and his team have a year or two to work out and plan a strategy to win a second referendum, for the SNP’s historic fourth term has set the clock running on indyref2.

A second referendum is now a matter of when, not if, and those who argue otherwise take the Union for granted.