There was a sense of disbelief about the fashion in which Scotland surged to the Grand Slam in the Five Nations Championship in 1984.

After all, it was the first time they had won the championship outright since 1938. And their only previous Slam had happened way, way back in 1925.

Which meant that precious few people who basked in that earlier success were still around to enjoy the festivities 59 years later.

Yet, with hindsight, the fashion in which Jim Telfer guided his squad to a historic achievement was instructive, as we prepare for the 2020 tournament.

The Scots weren’t favourites at the outset and had to battle past Wales in Cardiff before beating the hosts 15-9. They followed that with a convincing 18-6 win over England and then thrashed Ireland 32-9 – by five tries to one – but even then, nobody in the team was prepared to uncork the champagne prematurely.

Indeed, even as the Scotland players celebrated after securing the triple crown against the Irish – whom they tackle first in Dublin this season – there was a sense their exploits would not be fully complete until they had converted it into a grand slam.

Their indefatigable captain, Jim Aitken, for instance, wasn’t interested in resting on his laurels. “Most of the alickadoos [officials] at Murrayfield thought that was it after the Irish victory. I knew that a couple of them were saying that it wouldn’t matter if we didn’t beat France, because we’d already had a great season,” he declared.

“I replied that it would be a disaster if we lost the last match. We had to finish the job.”

Nobody was under any illusions it would be straightforward. The earlier performances of Les Bleus had left the England hooker, Peter Wheeler, describing them as “unbeatable”. Yet, with Telfer determined to pull off another masterstroke, and such test-class performers as John Rutherford, Iain Milne, David Leslie, Jim Calder, Iain Paxton and John Beattie committed to the cause, there were reasons to be optimistic.

It was a winner-takes-all situation and the Scots knew their opponents would fly out of the blocks and serious questions would be asked of their defence. But these were tough men; a dozen of the squad were from the Borders and had grown up together.

Rutherford recalls: “If you went to Mansfield Park or Netherdale and heard the crowd hurling abuse and their guys getting stuck in, you weren’t afraid of anything in rugby.

“I think there were occasions when we played better than we did in 1984, but we needed to show we could tough it out when necessary and we did.”

The hosts were certainly under the cosh in the early stages, with such talismanic figures as Jerome Gallion and Serge Blanco orchestrating their own brand of improvised magic. Time after time, it seemed as if their artistry would unlock the Scottish fortifications, and Gallion’s try put his side 6-3 in front at the interval.

But, considering how much they had dominated, it was a fragile lead for the visitors. Worse still, from their perspective, they gradually fell foul of the referee, Winston Jones, and Peter Dods was in impeccable form to punish their lack of discipline.

Then, on the hour mark, they lost the influential Gallion to injury in controversial circumstances when he was high-tackled by David [Leslie] at a line-out.

The tussle was poised on a knife-edge, but the Scots moved in front with a try that encapsulated all the qualities they had displayed throughout the campaign.

Telfer declared: “Blanco was caught under a high ball and driven way back. The impetus that gave us was crucial, and we scored from more or less the next line-out.”

Suddenly, Murrayfield erupted in a cataclysmic outpouring of emotion and, although some of the Scots were tired by this stage, the French were dead on their feet.

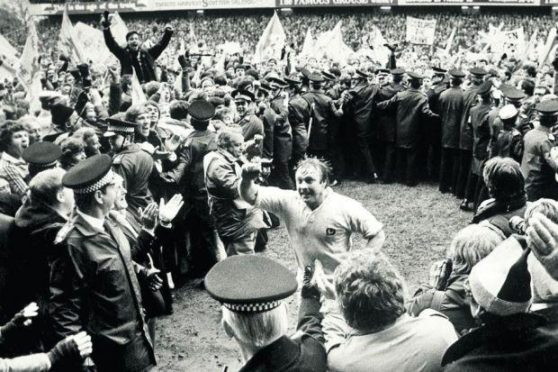

Despite Dods having a swollen eye, his vision was spot-on when he sealed the outcome with his fifth penalty, which sent his side 21-12 ahead. That was enough. At the climax, Aitken’s men leapt with joy and hordes of supporters invaded the pitch.

Rutherford said: “None of us had any experience of winning a grand slam – Scotland has last done it in 1925 – so we were both overjoyed and amazed at the reaction.”

The post-match dinner, by all accounts, was messy. Edinburgh rocked, Glasgow gallivanted, and, suddenly, rugby was all over the news.

It was the start of a golden period for the game in Scotland.