It’s two years tomorrow since Scotland’s cricketers shocked their English counterparts with an unprecedented victory against the No 1 ranked side in the globe at the Grange in Edinburgh.

Even as the dust settled on the heroics of Kyle Coetzer’s team in 2018, some of the responses were tinged with surprise at the fact Jock Tamson’s Bairns were any good at the game, which was deeply frustrating for those of us who adhere to the words of 10cc’s Dreadlock Holiday: “I don’t like cricket – I love it!”

Therefore, praise be for former Test star, Mike Atherton, who has offered the view that his greatest-ever England captain, was actually the Scot, Douglas Jardine, who led his men to success in Australia in the most controversial series in the sport’s history – and whose own ashes were scattered in the Highlands after his untimely death in 1958.

Atherton is an intelligent, perceptive character, so his words carry weight, although it might be too late to convince the sterner critics.

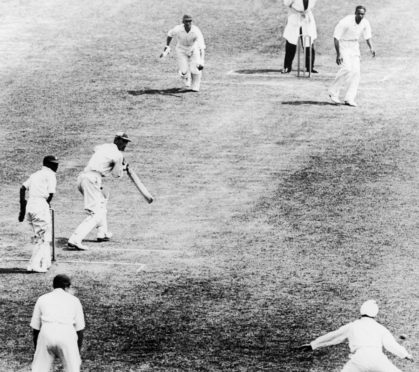

After all, as the architect of the Bodyline tactics which helped England orchestrate a stunning win during the 1932-33 campaign, Jardine’s tactics and temperament inspired fear and loathing, not merely from crowds at various venues, but as far up the diplomatic chain as the Australian High Commission and Westminster.

Even now, when one might have anticipated a calmer perspective, he is, for myriad observers, eternally associated with quintessential English imperialism and arrogance.

And yet, while he may have been born in Bombay on October 23, 1900, his parents, Malcolm and Alison, considered themselves proud Scots to their bootstraps, and their young son was educated in St Andrews, regularly visited the Highlands, and chose the remote beauty of Loch Rannoch as his final resting place.

His children, Euan, Iona, Marion and Fianach, subsequently devoted a great deal of their lives to the care of others – as a committed supporter of Nelson Mandela, Euan settled in Durban and was involved in the political upheaval which swept through South Africa until his premature death in 1997.

I remember speaking to Jardine’s daughter, the late Reverend Fianach Lawry, who was horrified at the fashion in which her father had been vilified.

She told me how she had sat through an ABC-produced TV series, which portrayed her dad as a diabolic combination of Bertie Wooster and Dr Hyde, and admitted to being amazed that so much vitriol had been flung when his only “offence” was, in actuality, a masterstroke which would, nowadays, have probably earned him a knighthood.

Whereas, in the 1930s, even some of the MCC committee members were happy to stick knives in Jardine’s back and both he and fast bowler Harold Larwood were made the scapegoats in the Bodyline affair, with one high-ranking executive saying in a letter to a colleague: “Between you and me, Jardine is insufferable and worse than any German I encountered in the [First World] War. I cannot abide the man.”

Perhaps, in the circumstances, it was hardly surprising the Rev Lawry offered a vigorous denial of the wilder allegations and claimed her father was a painfully shy individual, who never really recovered from the stigma attached to his name as relations broke down between London and Canberra.

She said: “It is a total misrepresentation of the man I knew and the idea he would deliberately set out to hurt players on the other side was anathema to him, but my father was very badly affected by the criticism hurled in his direction.

“He has been accused of supposedly being arrogant and cocksure when the truth was that my dad was a nervous person, who bit his fingernails like mad, and yet, because he wasn’t a great conversationalist at social functions, he wasn’t able to respond to the barrage of personal abuse which wrecked his career.

“It is tremendously sad his name has been linked with one of the most contentious campaigns in sporting history. It’s ironic that nowadays, he would be regarded as a hero by his compatriots, but of course, my family has been affected by what befell him.

“He had high standards, was immensely competitive and refused to be content with coming second when there was a chance of victory.

“But he was never mean or petty, and though he harboured a huge regard for Bradman’s ability, he knew you won’t win anything by sitting back and admiring your opponents. He simply acted in his side’s best interests and the picture which has been painted of my dad is completely unknown to me.”

Jardine isn’t the only Scot to have captained England. Mike Denness, from Bellshill, was given the role in the 1970s and Tony Greig had enough Caledonian ancestry to have been offered a place in the Scottish rugby team. But he was the only man who blunted Bradman’s bravado and masterminded a series triumph Down Under.

His daughter recalled: “For too long, he has been traduced as this win-at-all-costs Englishman, but that is nonsensical. He was ferociously proud of his Scottish heritage and we have all done our best to carry on that tradition.”

ONE LAST THING….Cricket will return across England in the next few weeks, with the Windies tourists arriving for a Test and ODI series.

Given the way the season has been wiped out across Britain, wouldn’t it be a positive move if the English authorities decided to help their Scottish counterparts?

What about inviting them to play ODI matches against England and the Windies? Or even a brace of T20s?

This would at least provide Cricket Scotland with some high-profile coverage for their furloughed players. As it is, the schedule is empty.

So what about it?