They were golfing trailblazers who created pieces of magic and mystique all across the world.

Anybody who has been braving the nightshift hours this week and watching the US PGA Championship at TPC Harding Park in San Francisco can’t fail to have been impressed by this resplendent course, which dates back to the 1920s.

And it was designed and brought to fruition by William Watson, one of the many Victorian Scots with a passion for the game who has left his imprint on the sport in countless different places.

Born in Kemback, near Cupar in 1860, as the first of seven children, there wasn’t a time when Watson wasn’t enthralled by golf and was inspired in this passion by his father, John, who was a member at St Andrews.

As a youngster, he became fascinated with course design and architecture and met his father’s friends who included Judge Martin Koon from Minneapolis.

That led to the Scot being invited to work on an initial nine-hole project in America and Watson, at 38, found himself boarding the RMS Etruria at Liverpool in October 1898 and embarking on a brilliant and remarkably prolific career.

His efforts helped establish the Minikahda Club in Minneapolis and he was subsequently involved in the design, redesign or construction of more than 100 sites across the US, from Virginia in the east to California in the west.

This all happened during a period when most Americans had still to be converted to the charms of life on the links, but the names on Watson’s cv – Belvedere, Hacienda, Interlachen, Annandale, Orinda and Olympic Club – still resonate among those who prefer a twist of traditional Scots whenever they stride on to the fairways and greens.

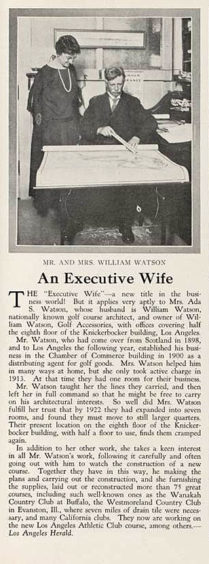

TPC Harding Park was one of his late works, being completed in 1925, but there’s a picture of Watson with his wife, Ada, at the Knickerbocker Building in Los Angeles, demonstrating how the couple transformed their previously all-male domain with her described as “the executive wife – a new title in the business world.”

Watson died in 1841, but left behind a rich legacy and, in the enforced absence of crowds at the first major of 2020, we were able to enjoy the fashion in which the world’s best players were tested in one of his truly transcendent settings.

He’s in very good company. Because, when it comes to creating majestic cathedrals of golf, Scots have always been among the most evangelical pioneers.

That was equally true at Augusta National, the home of the US Masters in Georgia, which will be staged, rather incongruously, in November this year.

Nowadays, the myriad features of this wonderful setting – including the azaleas and the dreaded “Amen Corner” with its rambling creek – have become etched in sporting folklore and are cherished by more than just golfing aficionados.

But they only came to fruition in the 1930s when Bobby Jones, the greatest golfer of his generation, sat down and discussed how to design the Masters course with Dr Alister MacKenzie, a former doctor and camouflage expert, who turned his talents to golf by creating some of the greatest courses throughout the world.

Remarkably, or perhaps not, Jones only considered two candidates for the job of architect in Augusta – the other was Donald Ross from Dornoch, another man whose legacy lives on at such places as Pinehurst No 2, Oak Hill Country Club and the Sedgefield Country Club in North Carolina.

Jones had developed a deep affection for the Caledonian links courses on his travels and considered it perfectly natural that a Scot should be in charge of constructing his fairway to heaven.

MacKenzie, who had served with the Somerset regiment during the Boer War, had been impressed by how his adversaries had adapted their campaign tactics to their terrain and his ideas were always based on the concept of working with nature.

By the time he came to Georgia and shook hands with Jones, he had fine-tuned his signature style and the list of global courses in which he was involved was staggering: from Cypress Point in California, to the Royal Melbourne Club in Australia, and the Old Course at Lahinch in Ireland, to the Portland Course at Royal Troon in Scotland.

Golf is a truly global pursuit in the 21st century, which makes it more difficult for Scotland’s current generation to make their mark in the game, although Oban’s Robert MacIntyre was among the competitors at the US PGA.

Yet, wherever you venture, there are gems to be enjoyed from the innovation, imagination and enterprise of these Scottish trailblazers.

TALKING of which, we should take time to mark the death of Jim Blair, a tough-talking former footballer from Glasgow, who became one of the most significant influences on the development of the All Black rugby team in the 1980s.

The New Zealand media have acclaimed the man who emigrated to Auckland in 1962 and became such an important figure in the country’s rugby’s development.

Former All Black coach, John Hart said: “We developed a totally new approach to skills training under Jim – with backs and forwards working on the same skills, and locks having the same skills as wingers.

“Particularly important was his individual conditioning for positions and people. Traditionally everyone had trained the same. Everyone ran round the field one way, then ran round the other way.

“But he introduced us to gyms and individualised training. And it made a huge difference. I point to him as being one of the pioneers of the game.”

Blair died last week from dementia at the age of 85. But Hart has no doubt that the All Blacks’ inaugural World Cup triumph in 1987 owed plenty to this uncompromising taskmaster.