He was known as Whispering Death on the cricket field when he was part of the all-conquering West Indian team of the 1970s.

But Michael Holding has spoken out forcefully and eloquently about the systemic racism of the sporting milieu in which he grew up and the horrible abuse which was dished out to him and his colleagues.

Controversy continues to surround the Black Lives Matter movement and the decision of players to take the knee at the European Championship has even been the catalyst for some supporters booing their own team.

In this climate, where one person’s justified protest is derided by others as virtue signalling to ‘Marxism’, even broaching the subject occasionally feels like trying to climb Everest with a piano strapped to your back.

Yet Holding hasn’t lost any of the resolve or resilience which was on display during his 60 Tests for the Windies, during which time he took 249 wickets between 1975 and 1987. After responding to the death of George Floyd last summer with a poignant and sustained oration on Sky TV, the former fast bowler has now written a compelling book Why We Kneel, How We Rise.

It’s not an easy read, but then it’s not supposed to be. There are no pat conclusions or simplistic panaceas for the insidious evil of racial prejudice as Holding investigates in depth the often inglorious history of the British Empire and its many links to the slave trade in Africa and the Caribbean. He is 66 and doesn’t expect the problem to vanish in his lifetime.

However, it’s the sporting superstars who have talked to Holding whose cumulative stories demonstrate the scale of the blight. Olympic and world sprint champion, Usain Bolt, recalled being in London for an athletics meeting and, after walking into a mall, noticing a security guard was following him, then being asked by a woman behind the counter: “Are you sure you can afford it?” when he tried to buy a watch.

American sprint sensation, Michael Johnson, also endured waves of casual racism from his college days, and his account of going to university in Texas, is all the more unsettling because he describes it in such measured terms.

He recalled: “I was targeted, for sure, but I fought back. It might be the n-word or something like that, so you push back. This is what happens, people say these things and I have to stand up and defend myself.

“But is there anything that can be done to stop it? I can stop it in a moment with a fist on your lip, but that’s it. It has taken years, decades even, for me as an individual to recognise that I need to do something about it.

“After my athletics career, I started to feel like I needed to be part of the solution with regard to making change, actively making change. I always felt, as a black athlete, that I had a responsibility to my black community to represent them well and defy the stereotypes.

“But I think back to the discussions I’ve had with my son about how to behave if the police turn up. He’s 20 now, but the first time we spoke about it, he was in his early teens. He’s tall, he’s athletic, he was starting to be independent and go out on his own. And I think back and it’s crazy. At what point did this [worrying about the police] become normal? My dad had the same conversation with me. It’s ridiculous, absolutely ridiculous.”

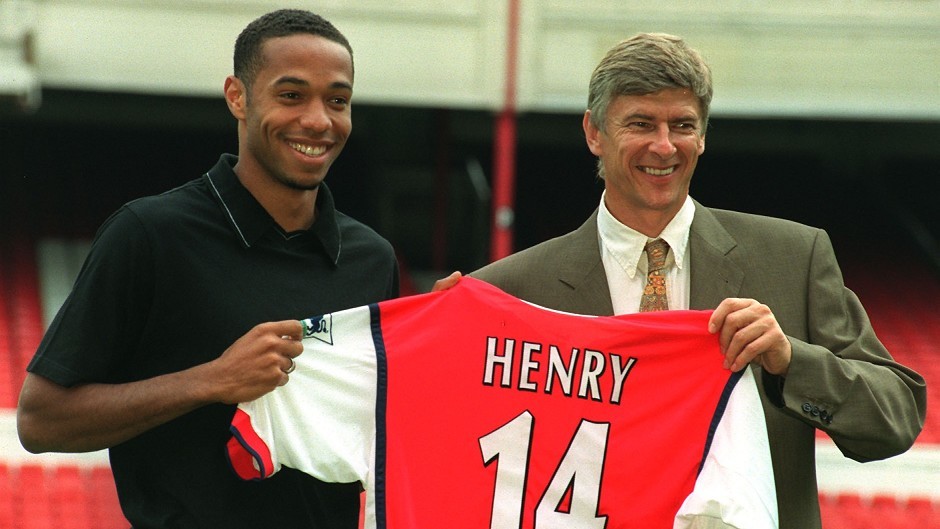

Holding and his interviewees, who also include tennis Grand Slam winner Naomi Osaka, football coach Hope Powell, South African Test paceman Makhaya Ntini and France and Arsenal footballer Thierry Henry, are all convinced that education is the key priority in tackling racism.

This isn’t a white-bashing book for the sake of it: on the contrary, Holding accepts that prejudice stretches beyond the colour of one’s skin in many countries and that attitudes towards women and gay people in some parts of Africa and the Middle East go back to the Stone Age.

But nonetheless, the recollections of somebody such as Henry emphasise why this issue has generated so many headlines. His dad was from Guadeloupe and his mum from Martinique, and he had a “tough but fair upbringing” in a block of flats in the Paris suburbs, known as banlieues, which are still producing sublimely gifted players including wunderkind Kylian Mbappe.

However, it all changed when Henry went to a small community in his early teens. He was warming up for a game with teammates from Senegal and Nigeria. Then suddenly:

“Silence. Nothing. Even the wind stopped. I can remember the look on the faces now, but I didn’t know that look, so I was like: ‘What is wrong with these guys?’ And then it was: ‘Go back to your own country’, and ‘Black this’ and ‘Black that’, ‘Arab this’ and ‘Arab that’.

“My way to answer was to beat them through football without reacting to what they were saying. And I used to look at them in a cocky way. Because that was my only way to show them.”

Holding accepts that not everybody is born with the talent possessed by himself and Bolt, Johnson and Henry. But he will keep campaigning for greater equality, diversity and fairness.

As he concludes: “I don’t expect to be around to see the fruits of that labour and love. It is going to take time. Maybe as long as my six-year-old grandson getting to the ripe age I am now.

“But like my mom said to me, I think I can safely and happily say to him and to you: ‘We’ve got a chance”.

Why We Kneel, How We Rise is published by Simon & Schuster