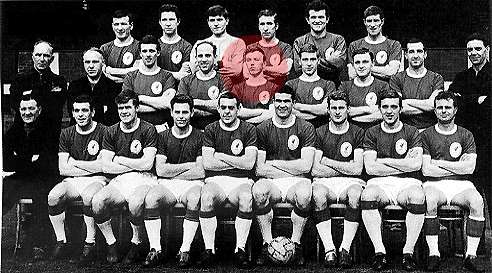

He was one of the Shankly Sons who followed in the footsteps of the Busby Babes, on a long and winding road from Torry to Tranmere Rovers, via Liverpool and Port Elizabeth.

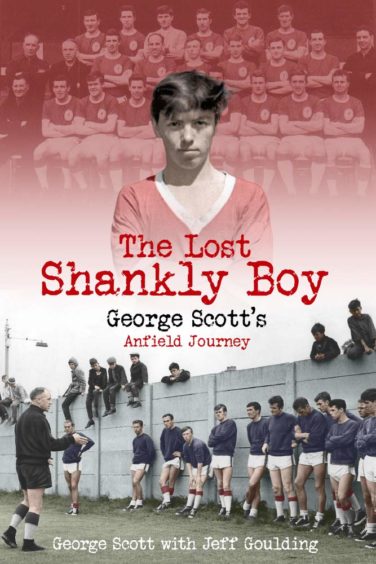

And, even now, 60 years after George Scott left the Granite City at just 15, against his parents’ wishes, and journeyed further than he had ever gone before to Merseyside, there’s a sprightly tone in his voice when he talks about his peripatetic football career, which he has chronicled in an autobiography The Lost Shankly Boy.

It’s a compelling story, which includes an extraordinary array of anecdotes about Scott staying in digs with Anfield legend Tommy Smith, returning to Aberdeen FC and running rings round Rangers great John Greig, being employed as a security guard in a South African shanty town and working as a sales rep when he met Hollywood star Elizabeth Taylor.

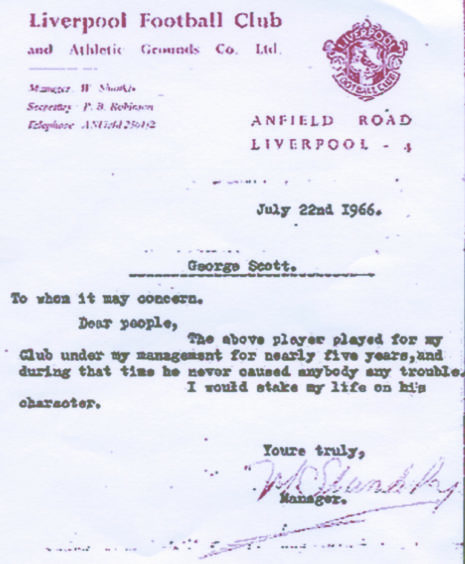

And there is even the reference which Liverpool’s legendary manager, Bill Shankly, wrote for him after the youngster sustained a serious cruciate ligament injury in 1966.

It’s on official club notepaper and states: “Dear people, George Scott played for my club under my management for nearly five years and, during that time, he never caused anybody any trouble. I would stake my life on his character.”

Scott clearly thought the world of Shankly and, amid the Swinging Sixties, that passion was reciprocated, even though the north-east player couldn’t quite break into the First XI in an age where there were no substitutes.

He said: “I was in the squad for the FA Cup final in 1965 [when Liverpool beat Leeds 2-1] and Shanks later described me as the 12th best player in the world.

“He had this aura about him which made you realise why he gained such an exalted reputation. You always felt his presence even before you saw him and he had a way of building you up.

“I remember he came up to me and said: ‘By heavens George, you’re looking fit. I heard you scored four for the reserves on Saturday. Well, there was a lad in the other side who is going to play for England and he never scored at all.‘

“He was talking about Alan Ball. These comments and the way he treated you properly had a way of giving you a positive lift.

“Bill Shankly was amazing – probably the greatest football man who ever lived – and he looked after me long after I had left the club.

“I always said five years with Bill was worth ten years at any university.”

Scott, who had been recommended to the Anfield club by his school caretaker Jim Lornie, returned to his roots and received a signing-on fee of £1,000 at Pittodrie, which he spent on a new car, and drove it out of the garage in a spirit of giddy exhilaration.

Why not? He was still just 20 and made an instant impact in his early days at Aberdeen.

He recalled: “I had supported them since childhood, so I was determined to prove what I could do and I scored on my debut after just 13 minutes against Clyde.

“Next up were Rangers and our supporters were thrilled when we beat them 2-0 at Pittodrie in front of a crowd of 28,000. There were nine Scottish internationalists in the visiting team that day, including the Scotland captain Greig, but I remember putting the ball through his leg while nutmegging him and hearing him chasing me and asking in very strong terms the name of the hospital I would prefer to wake up in if I ever did it again.

“I felt really confident about my future, but sport can be cruel and when I suffered the cruciate injury, I was released at the end of the season in the summer of 1966. I was out of work at 21, having left school at 15, with nothing to fall back on and no qualifications.”

Scott has never been afraid to embrace fresh challenges. After receiving his prized reference – which was printed with one finger on Shankly’s little typewriter – he worked in a biscuit factory, before joining South Africa Premier League team Port Elizabeth City.

He and his fiancé Carole were married on July 30 1966 – the same day England won the World Cup – and he enjoyed significant success in the Cape as the league’s leading scorer.

However, he was appalled at the pervasive influence of apartheid in the country – “I would play football in the streets with the local black kids, but was told not to, because it wasn’t the done thing and wasn’t ‘right’, and seeing such racism up close was shocking” – and the couple came back to the UK in 1968.

That led to Scott joining Tranmere and although he continued to prosper on the pitch, he realised he needed to search for another job once he had hung up his boots.

Once again, the Shankly testimonial proved invaluable when he attended an interview with Nestle at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool city centre. He was hired on the spot and subsequently enjoyed his tryst with acting and political celebrities.

He said: “Elizabeth Taylor was promoting her perfume at the Ritz in Paris and I was there with some other sales guys. While she was chatting to us, her personal assistant came over and told her that she had a guest.

“Well, it just happened to be Henry Kissinger. We sat there in disbelief as he walked in and they started talking. It was a brief taste of a totally different world.”

Scott is a blithe character, somebody who has just recovered from five-way bypass surgery in hospital and, although he lives in Liverpool, he still relishes his links with Aberdeen.

He concluded: “I loved being involved in football and so much of it is about being in the right place at the right time.

“I enjoyed working on the book as well. And I know it will be available in Waterstone’s in Aberdeen. Hopefully, it will spark a few memories in my home city.”

The Lost Shankly Boy is published this week by Pitch.