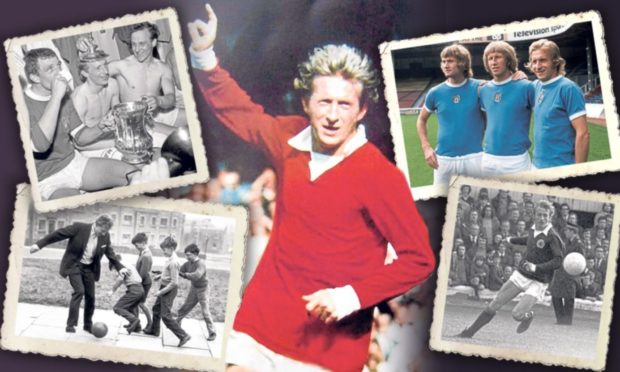

Tens of thousands of people lined the streets when Denis Law was accorded the Freedom of Aberdeen in 2017.

They congregated in such numbers to celebrate a man who excelled for Scotland and Manchester United and orchestrated magical mayhem wherever he ventured: a lad who was called The Lawman and the King of the Stretford End, who visited his roots at regular intervals and helped new generations of youngsters to play the game he loved.

It’s one of the strange aspects of his career that he was never in contention for a place at his home club, Aberdeen, despite showing plenty of potential as a youngster.

But there again, Denis, who has revealed that he is battling mixed dementia, has always blazed his own, idiosyncratic trail on and off the pitch.

It’s a long time since he entered the world in February 1940 and grew up at 6 Printfield Terrace in Woodside, but one of the things that makes him special is how much he has been prepared to talk about those early days as a tenement child.

Although he has performed at the highest level, become the only Scot to secure the prestigious Ballon d’Or (in 1964), won the hearts of the Old Trafford faithful by scoring twice on his debut and broke the hearts of England’s World Cup-winning team a year later at Wembley, there’s not a trace of the pampered prima donna in his personality.

He has never forgotten the grinding poverty he lived through as a youngster and has spoken openly about his mother having to hand in her husband’s only suit to the pawnbroker’s when he went away to sea on a trawler every Monday.

In short, while he might have decamped to Huddersfield, Torino and Manchester, where he still lives, his spirit and his soul have always been in the Granite City.

As he recalled: “I didn’t own my first pair of shoes until I was 14. I could have had free shoes, but they were like big tackety boots and we were too proud to take them, because everybody would know they were handouts.

“Whenever I look back at how we lived when I was a child, it’s probably difficult to explain to the modern generation.

“Our house had no carpet, no central heating and no television. There was a pantry instead of a fridge and I didn’t eat any food during the week except soup and sago pudding, which looked like frogspawn.

I never really got to know my dad as much as I would have liked.”

“There was just one bathroom for the entire family and we’d have a bath every Sunday night, because that was the only time there was any hot water, but none during the week.

“We just got on with it because there was nothing else for it: at that time, all mining and fishing families lived in similar, straitened circumstances and, as a result, I’ve always thought they must be the two hardest jobs in the world.”

Denis never had ambitions to follow in his father’s footsteps. Football provided an alternative, but he didn’t have the sea legs, in any case.

He said: “I went out on the trawler with my dad just the once from Aberdeen harbour.

“It was a beautiful sunlit day and the water was calm when I joined him, but even then, the little boat was bobbing up and down the further out we steamed.

“As I struggled to keep down my breakfast, I remember thinking: ‘Good grief, this is not for me’. I never really got to know my dad as much as I would have liked.

“But I always had admiration for him and others like him, considering that every day these men went down the pits or out to sea, they were risking their lives and working in often terrible conditions to earn a barely adequate living for their families.”

Even as he was growing up in Aberdeen with a squint in his eye that forced him to wear corrective glasses, this little skelf of boundless energy was in thrall to the game with a ball, excelling at keepie-uppie under street lamps in sun, rain or snow.

Saturdays were reserved for Aberdeen Lads Club duty – at least, after he had finished representing his school.

There were few community facilities in the early 1950s but he and his friends weren’t deterred by any obstacles in their path.

He said: “The club didn’t have a youth team when we arrived on the scene so, along with a next-door neighbour, Sid Thompson, we formed our own and called it the ALC Colts.

“It was an under-16 side and, needless to say, we were skint. But we used to go round the houses in Printfield selling raffle tickets to buy some shirts and socks.

The furthest we had ever been as a family was Stonehaven so this was a huge adventure and a shock to the system for everyone.”

“Talent abounded in our area and there were some interesting characters at the club, including John ‘Tubby’ Ogston, who went on to have a fine career in professional football with Aberdeen and then Liverpool and Doncaster Rovers.

“With so many talented, enthusiastic lads around, it was no wonder that Aberdeen Schoolboys and the Lads Club were successful.

“Even as young as under-12s, we were doing well, reaching the final of the Scottish national competition, and we played at Motherwell’s Fir Park, which was my first experience of being away from home – we couldn’t afford holidays – and playing on such a big ground.

“We also reached the under-15s final and I played with Alex Dawson, who went on to make a name for himself with Manchester United.

“He was a major talent and nobody was surprised when he headed off to Old Trafford.

“He was a tank of a centre forward and he actually broke into the United team after the Munich disaster in 1958, and helped them reach the FA Cup final that year.

“After that, he moved on to Preston where he became known as the Black Prince of Deepdale.”

Denis didn’t have any vast ambitions in these formative years.

He was hardly any threat to Hercules or Adonis and, as he recalled: “I was only a little boy, undernourished, under-developed, and weighing in at eight stone with a terrible squint. But then the chance came out of the blue to go for a trial with Huddersfield Town.

“Their Scottish manager, Andy Beattie, had a brother called Archie who lived a mile or so up the road from us in Aberdeen and occasionally watched our junior matches.

“It never occurred to me at the time whether Aberdeen FC would be interested in signing me or giving me a shot.

“Archie would keep an eye on up-and-coming players in the region and send the promising ones down to his brother to have a look at.

“I didn’t even know where Huddersfield was. The furthest we had ever been as a family was Stonehaven, so this was a huge adventure, and a shock to the system for everyone.”

Denis freely admits that all the honours, plaudits and prizes he achieved during his illustrious career followed a distinctly underwhelming arrival in the West Riding.

Andy Beattie was waiting on the railway platform, took one look at the youngster, and remarked: “The boy’s a freak. I’ve never seen a less likely football prospect’.

“I could understand why. I was 15, stood between my brothers, George and John, and I was 5ft 3in, with round glasses correcting a squint and a huge boil on my cheek which was an angry red and about to burst.

“I must have looked a right miserable bag of bones.

“But I was down there for a week, the football we did was mostly five-a-side practice matches, and they wanted to see how comfortable I was on the ball and whether I was as weak and fragile as I looked. And I wasn’t, I can tell you that.”

Soon enough, Denis was offered a contract and the rest, as they say, is history. It still seems curious that nobody at Pittodrie ever spotted his potential, but they didn’t.

As he said later: “The only trials I was involved in were at Huddersfield and, as for being offered a place at Aberdeen FC, I can state categorically there was not a single word from that direction.

“If Aberdeen had a scout, he was elsewhere at the time.”

Eventually, even as Denis thrived on the field, he received an appointment back in his home city to have corrective surgery on his eye and although the bandages made him look like the Invisible Man, the procedure brought a massive transformation.

He said: “It completely changed things. For the first time in a decade, I could look at anybody without my glasses and knowing my eyes were straight. I was ecstatic.”

Denis has never shirked a challenge in his life and has enormous admiration for the NHS.

He might have “good days” and “bad days” in the future and football’s links to dementia have cast a blight on too many players from his generation.

But he will have the good wishes of everybody in football and the north-east public.