It’s a long time since Hungary were a force in world football. And you could say the same about Scotland.

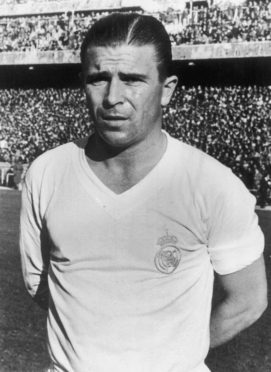

But, once upon a time, Ferenc Puskas, the little maestro with a shimmy in his step and an insatiable relish for life, thrilled everybody he met during a whistle-stop tour of Caledonia.

The two nations will lock horns in a friendly tussle this week and it’s safe to declare there won’t be anybody on the pitch with the mercurial brilliance of Puskas, the “Galloping Major”, who died in 2006.

Yet I was fortunate enough to talk to him, as he looked back on meeting some of the Scottish stars from the Swinging Sixties, including Jim Baxter and Denis Law.

Even in his seventh decade, it was clear his memories of the famous 1960 European Cup final between Real Madrid and Eintracht Frankfurt at Hampden Park would never be erased.

For many people, it was the greatest of all football dramas and Puskas scored four times as the Spanish club demolished their opponents 7-3, en route to a fifth successive trophy in front of 130,000 fans.

Puskas truly was a nonpareil, a character who performed with an infectious joie de vivre. But he never lost his connection with the people who watched him perform.

As he told me, Glasgow was one of his favourite places. “It was remarkable, the amount of affection that the people of the city showed towards us.

“Every time we moved forward, they were shouting and bellowing and encouraging us to keep trying new things.

“Maybe it was because I was a member of the Hungarian team which twice beat the English [6-3 at Wembley and 7-1 in Budapest] or maybe they just enjoyed the way we played the game.

“Whatever the reason, at the final whistle, the Scots were cheering so loudly you would have thought one of their own teams had just become the champions of Europe.

“And I met so many Scottish people that night who were thrilled for us. I loved it and it has stayed with me.

“I think when you are able to look back on evenings such as that one, you never really grow old.”

With hindsight, Scotland’s warm embrace of Puskas was unsurprising.

As one of life’s peripatetic souls, the Hungarian star loved tackling new challenges, visiting bars and restaurants, and accepted every party invitation as if it was his last.

He was slapped down by FIFA with an 18-month suspension for embarking on an unofficial tour of Brazil, as the prelude to arriving at Real Madrid.

And thereafter, he came close to signing for Manchester United in the months after the Munich air disaster in 1958.

He told me: “After I was banned by FIFA, I panicked a bit about what the future might hold. I couldn’t play anywhere, even though Manchester United tried to borrow three of us after they lost all those people in that terrible tragedy.

“I was keen for the move to go ahead – who wouldn’t when you looked at a place like Old Trafford? – but the English FA refused.”

Puskas reminisced about some of his contemporaries and it was obvious he held a high regard for Baxter (“He could do anything with a ball”), Law (“There was nothing of him, but what a talent”) and John White, who was fatally struck by lightning in 1963. (“We were totally shocked by that. He was a genius”.)

But he thrived at a time when individuals were less important than the sum of their parts.

As he stated: “If you ask me what makes a great team, I would answer that it’s essential to build very close relationships between the players.

“That’s how it was at Real in my days. After we had trained, we usually stayed together all afternoon, drinking wine and soda water and beer, and eating good spicy sausages.

“It might not have made us fit, but it built a bond between us, and that was a big factor during our tougher assignments in the European Cup.

“I’ve never believed in filling up your head with tactics and jargon. Looking back to Hampden, it was true that we created the biggest sensation of our time.

“But there was no secret to it. We had excellent players who knew how to keep the ball and pass it quickly, and we were 11 men who always knew where the rest of our team-mates were.

“We went, we won, we came back. It was simple, but it was effective, and we never forgot we were entertainers.”

As a vaunted member of football’s international Hall of Fame, Puskas could hardly have been more modest or self-deprecating.

And it was evident the statistics and baubles meant far less to him than the bonhomie and camaraderie.

His parting words were: “I don’t bother myself with what I might have earned if I had been born 40 years later, that doesn’t matter.

“We enjoyed ourselves immensely and I played football to score goals, not win prizes. The fact that I did both in my time was a bonus.”

No wonder Scotland warmly embraced this talismanic character.