It was one of those unbelievable, mildly hilarious, mildly heart-breaking incidents which have summed up Scotland’s faltering efforts on the World Cup stage.

And the fact it involved Willie Miller and Alan Hansen, two of the most gifted footballers who have ever pulled on their country’s shirt, demonstrated another truism. Namely, that nobody has been immune from the thud and blunder which has bedevilled our representatives on the global stage.

It was 40 years ago this week when Jock Stein’s squad launched their campaign in the same group as New Zealand, Brazil and the USSR at Spain 1982.

By today’s standards, the veteran manager had an embarrassment of riches at his disposal. Ten of the 22 men had participated in European finals. Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness, Alan Hansen for Liverpool. Alan Brazil, John Wark and George Burley for Ipswich. Allan Evans for Aston Villa, Joe Jordan and Frank Gray at Leeds and John Robertson for Nottingham Forest.

Then there were another seven players who had won league titles with their clubs. Danny McGrain and Davie Provan at Celtic. Alex McLeish, Willie Miller, Gordon Strachan and Jim Leighton at Aberdeen. And Steve Archibald had picked up the Scottish league at Pittodrie, as the prelude to moving south and securing back-to-back FA Cups with Tottenham Hotspur.

In short, there really were no excuses for these individuals not to make a serious impression on the tournament. And they began well enough with a 5-2 victory over the Kiwis, even if a few nerves started jangling after the minnows reduced the deficit from 3-0 to 3-2 before normal service was restored.

Brazil, replete with class and quality in their ranks, were always going to be a formidable proposition and, although David Narey’s stunner or “toe-poke” (the latter was the late Jimmy Hill’s notorious description of the goal) sent his side in front and the match was all square at 1-1 at half time, a dizzy combination of sweltering heat and sumptuous samba talent eventually consigned the Scots to a 4-1 defeat. A tough lesson, but no disgrace.

That left the Stein brigade with a simple equation. They had to beat the Soviets to advance to the next stage and, on the evidence of what the USSR had already served up, that was by no means an impossible task.

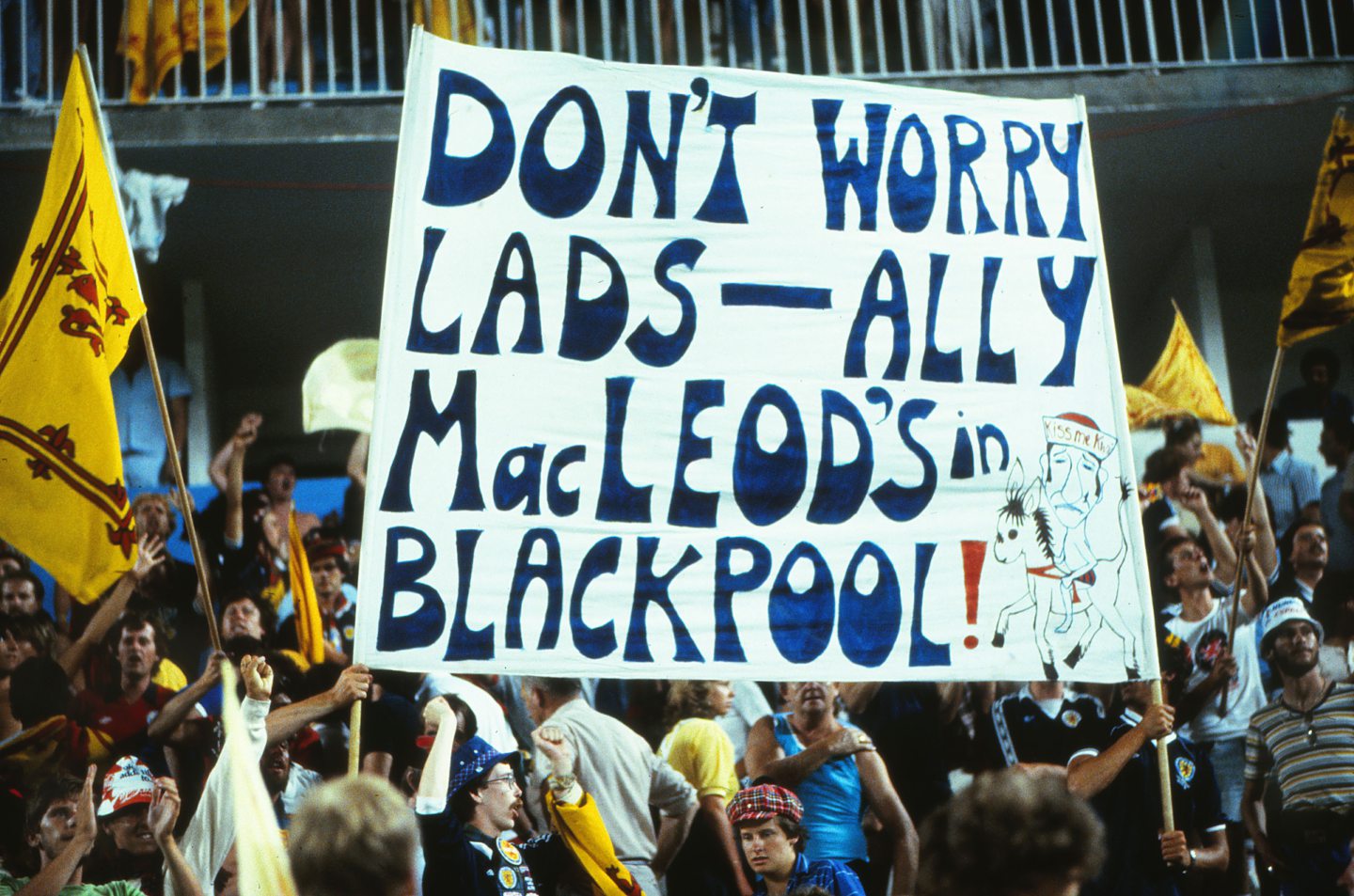

The Tartan Army billed the contest as “Alcoholism v Communism”, their number was boosted by the arrival of James Bond himself, Sean Connery – who sat in the crowd with his compatriots – and there was the usual blend of optimism and trepidation as the fans arrived at the stadium in Malaga.

In the early stages, things went swimmingly, with Jordan opening the scoring after 15 minutes, and there were plenty of hints their opponents were no world-beaters, but Scotland couldn’t orchestrate too many clear chances and the match became a tense war of attrition. Stein urged his troops at the interval to focus on keeping possession and pressing their rivals, but even these vastly experienced performers were unable to shrug off their anxieties.

It was torture watching that second period. There was a sense of inevitability when Aleksandre Chivadze equalised on the hour, but it was symptomatic of the contest that he unwittingly swerved his shot past Alan Rough despite failing to strike it properly. One or two of the Scots looked disconsolate, others shook their heads and let their shoulders slump, and it was almost as if they were preparing for the roof to cave in. Sadly, their fears were justified.

And yet, it was still remarkable when Miller and Hansen, normally two of the most dependable, classy defenders in Europe, conspired to collide with each other in the 84th minute; a calamitous mix-up which allowed Ramaz Shengelia a clear sprint on his way to slotting the ball past Rough.

Perhaps, with hindsight, Stein should have partnered Miller with his stalwart Dons colleague McLeish, who was on the bench along with the likes of Dalglish. But, to be honest, it was the sort of once-in-a-million-years debacle which appeared to be de rigueur for the Scots in World Cup combat.

If that was frustrating, the final scenes were increasingly maddening for those of us on the periphery. Souness surged forward with time running out and levelled the score at 2-2 and, once again, there were precious slivers of hope. Thereafter, Scotland poured forth like The Charge of the Light Brigade and might have stolen the spoils as they swarmed round their adversaries.

Why, you might ask, couldn’t they have done this much earlier in the tussle and built up the sort of momentum which might have shattered the Soviets’ spirit? But, when it happened, it was too little, too late, a lot of sound and fury which signified nothing but their elimination.

Elsewhere in the competition, England topped their group and Northern Ireland beat Spain to win their section, which merely reinforced the feeling that the Scots were their own worst enemies 0 the kings of wishful thinking.

After all, this was their third successive World Cup since 1974 and their record read: Played 9, Won 3, Drawn 4 and Lost 2 (against Peru and Brazil), which should have reaped a bigger reward and hinted at a lack of mental toughness.

Still, these were the days when we actually qualified!