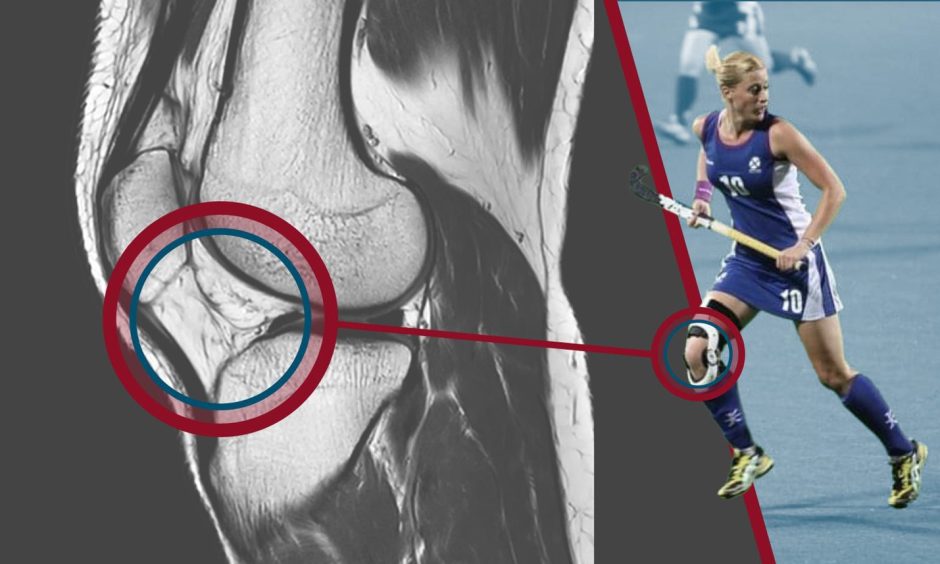

Aimee Clark uses her own experiences of ACL injuries to inform her work as a physiotherapist at the SPEAR clinic in Aberdeen.

We spoke to Clark to find out more about what is involved in the rehabilitation from an anterior cruciate ligament injury as part of The Press and Journal’s special investigation into the growing number of ACL injuries women’s football and how it is affecting players in the north of Scotland.

Research shows female athletes are up to six-times more likely to sustain a non-contact ACL injury than their male counterparts.

Clark, a former hockey player for Scotland, suffered an ACL injury three times – twice in her right knee and once in her left – and damaged the posterior cruciate ligament in her right knee.

ACL injury inspired physio role

Her experiences with the injury “inspired” Clark to become a physio, qualifying in 2013 from RGU and then going on to work for Aberdeen FC for five years.

Throughout her career, whether as a physiotherapist at a clinic or at a club, she has helped several patients – male and female – progress through their ACL rehab.

The priority throughout recovery, Clark says, is hitting specific goals, which is a more effective approach than from when rehab used to be determined by the length of time.

“Back in the day, it always used to be you’re out for nine months, but now it’s more goal focused over a period of time,” said Clark.

“When you achieve a certain goal then you can safely move on the next phase.

“Some people will respond quicker to those goals and that can depend on the amount of time they are working with a physio or their access to gym facilities.”

Clark describes the goals as being in six different phases: pre-operation, initial post-op, proprioception, strength, early sport training and returning to sport.

Such criteria might include reducing swelling, regaining movement in the knee, neuromuscular control, single-leg exercises such as squats and calf raises, and – as recovery progresses – the aim is to be able to compare your affected leg as close as possible to the non-surgical knee.

Recovery from ACL injury can be long and arduous

ACL injury rehab can be a monotonous process where physios like Clark plead patience with her patients as she does her best to keep sessions as engaging as possible.

“Recovery is hard and you can tell in people’s demeanours that they may be finding it difficult or are getting bored,” said Clark.

“It’s about trying to keep the patient focused and the goal in mind is to get back.

“Keeping rehab fun and specific to their sport can help a lot. It can help trying to uplift them because once you do your ACL it can be all-consuming. It can be all you talk about, see on social media or hear on the news.

“It can be a long nine, 10 or 11 months of just that word, especially when they are not playing their sport for a year.”

It’s about trying to keep the patient focused and the goal in mind is to get back. Keeping rehab fun and specific to their sport can help a lot.

Recovery may be goal-led, but time is of the essence as research shows coming back too early – before nine months – increases the likelihood of the injury happening again up to seven times.

Clark also believes there are ways for clubs to safeguard their athletes before injury occurs as she recalled how her former coach adapted his training methods after players had endured knee injuries.

“In order to and reduce it from happening, it would be doing appropriate warm-ups – with regards to plenty of proprioception and banded stuff,” said Clark.

“It’s about trying to get training up to a speed and level of what a competitive match would be.

“If athletes are training at that level more consistently it helps – these injuries happen more in that competitive environment, so it is just ensuring the level of intensity is right and it’s consistent.”

Pain and trauma of injury can cause mental health issues

Clark can relate to a lot of the people who she helps and knows all too well the trauma that can come with suffering such a devastating injury.

The first time she did her ACL in 2006 could not have happened at a worse time, as she was in the midst of preparing to represent Scotland at her first Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, Australia.

“The first time I was 21 years old and it was excruciating pain,” said Clark. “I felt sick.

“It was before I was meant to go to the Commonwealth Games, so I was more devastated about that because it was only a month away.

“And then a year later I was back playing and lunged awkwardly and it was instant. You just know the pain. You feel sick to your stomach.”

The Commonwealth Games did not elude Clark ,though, as she featured for Scotland in 2010 in New Dehli – but she would go on to sustain two more serious knee injuries, with the most recent being in 2017.

And having experienced setbacks during her own sports career because of injury, Clark knows the toll it can have on an athlete’s mental health.

“There is a lot more focus around mental health now when I did my ACL in 2006,” said Clark.

“There wasn’t much resources or consideration for that back then and that’s where I always have a think about my patients about how their mental health is: how are they feeling and how are they coping?”

Although Clark admits in her day job she has not seen an increase in the amount of female footballers seeking treatment for ACL injuries, she agrees it is an area which requires more research.

“Women’s football is growing so they are training more and playing more competitive games,” said Clark, who also used to play football for Inverness.

“I’ve had a patient who wears the new Nike football boots where the studs are designed in a rotation and she says they feel good, so that is a step in the right direction in regards to addressing possible causes.

“It definitely helps if you’ve got the right kind of data and any information or research like it would help a physio.

“We can give that information out to patients and give them advice from it for during their recoveries.”

Conversation