I didn’t think I would ever feel so relieved that the only serious football injuries I ever had were broken bones.

My (un)promising player career was cut short when I was about 21 years old thanks to a broken nose, sustained by taking a knee to the face during a match.

It was the second bone I had broken during my time as a goalkeeper, with the first being a broken wrist from saving a free-kick when I was only around 12.

I felt quite cool rocking up to school in my purple cast after breaking my wrist and being able to tell my class-mates about my goalkeeping heroics.

But I can’t say I felt the same about having two black eyes and a dodgy looking nose when that blow to my face happened several years later.

Injuries are part and parcel of football and I have had my fair share of staved fingers and sprained ankles, but nothing more serious than a fracture.

And, of course, fractures are serious, but I knew when they happened I could be back playing after six weeks or so… I could have even played with a broken nose by donning a Batman-esque mask if I had so wished.

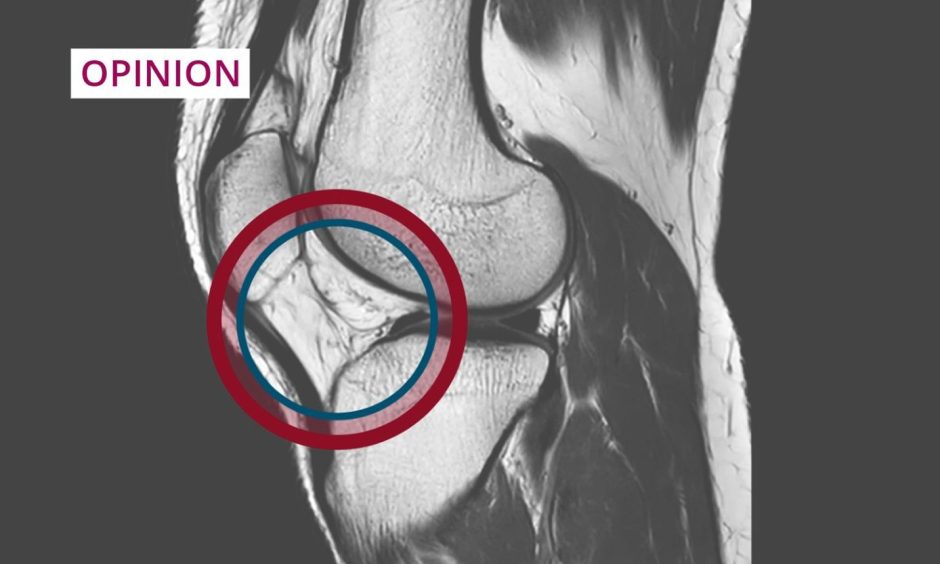

ACL injuries a physical and mental blow

The same can’t be said for those players who damage their anterior cruciate ligament.

When a player goes down with an ACL injury, they are staring down the barrel of at least nine months of rehabilitation.

I have spent the last month or so in my job as a sports journalist researching, reading and speaking about ACL injuries as part of The Press and Journal’s latest women’s football investigation.

I spoke to four north players who have been through it: from the excruciating pain to the mental toll of being sidelined from the sport they love.

It was clear when I spoke to all of the players how much it had affected or was still affecting them – the exasperation in their voice clear when they spoke about the rehab milestones they have or were yet to hit.

Although I have not suffered an ACL injury, I can relate to the feeling of fear about returning after being on the sidelines.

My broken nose called time on my playing days. I broke it as I dived at the feet of my opponent to get the ball, which I got, and she followed through in her running motion and her knee collided with my face.

The injury depleted my confidence. I had the fear of it happening again, so I was reluctant to do the things goalkeepers have to do to do their jobs properly.

I knew it was a freak thing and chances are it wouldn’t happen again, but the fear was still there.

For those who sustain ACL injuries, they don’t have the luxury of such rationale.

With those injuries often occurring via non-contact and the result of something as endlessly repeatable as just changing direction.

Having done their ACL already, there is a chance it could happen again and there’s not much they can do – other than mentally prepare.

And even if I was to get an injury like a broken nose again, I could decide to play on and take the right precautions to protect the injury or accept a six-week absence from playing.

I may have had the same fear about returning from an injury, but the mental and physical stakes for those who have done their ACLs are completely different beasts.

‘More than just a sports injury’

Everyone’s rehab will be different but the common thread is the physical landmarks they must reach through in arduous recovery, while having to navigate the mental rollercoaster of being sidelined.

I did not want this project to only be a call for more research, as much as it is needed, but more an opportunity to highlight how these experiences are more than just a sports injury.

Karen Mason told me how the pain affected her quality of life and her day job as a teacher.

Rachael Boyle said how all she wanted was to be able run around with her kids again, while 17-year-old Kaylah Cruickshank – whose senior career has barely started – could not yet comprehend the rehab she was about to endure.

Of course, more research needs to be done to find out more about why these injuries keep happening and what can we do to safeguard players.

But I hope by working on this project the players I spoke to felt listened to and their experiences validated, while others better appreciate – like I now do – the resilience and strength they must have to get themselves back on the pitch.

Conversation