Nothing’s left to chance in preparing for the Olympics these days. Whether it’s providing competitors with Lottery funding and specialist coaches or teaching them about nutrition and psychology, those who reach the medal podium have the benefit of an intensive training programme.

There was none of that in Britain 60 or 70 years ago. And, although a few individuals successfully transcended obstacles, there were others who shot into the spotlight on the strength of their talent, only to have their progress stopped abruptly in its tracks.

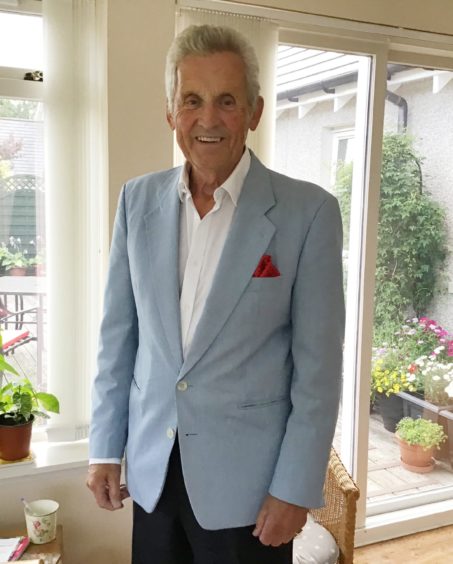

Just consider the case of Ian Black, the remarkable Inverness-born swimmer who turned 80 last month and, for a short time, was considered one of the best, if not THE best in his pursuit, in the build-up to the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

The evidence certainly vindicated those who championed him. Black remains the youngest-ever recipient of the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award and was only 17 when he was presented with the coveted silver trophy in 1958, finishing in front of Bobby Charlton and Stirling Moss; an outcome which the teenager described to the audience as “most unexpected”.

As his country’s first winner, he stepped on to the stage at the Grosvenor Hotel in London to the strains of “Scotland the Brave”, said it was particularly gratifying that the public had chosen the winner and added: “To be held in the affection of the Scottish people, even for a while, is something to celebrate.”

Yet there was a sting in the tail. At exactly the moment when one might have expected the authorities and his school to get behind him in his bid to chase further honours, the doors were slammed shut in his face. It seems incredible, but these were the days of amateurism and the pop-star publicity which surrounded the Aberdeen-based Scot was regarded with suspicion and, on occasion, downright hostility.

This was doubly disappointing because 1958 really was an annus mirabilis for the talented Scot with the memorable nickname The Human Torpedo.

He secured gold medals in the 400 metres, 1,500 metres freestyle and 200 metres butterfly at the European Championships and another three medals – including gold in the 220-yard butterfly – at the British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

The youngster, who wore a MacGregor tartan dressing gown poolside, said simply: “You could say that I had a golden patch – six months in which everything happened.

“But when I won the BBC award, it was still quite new. On Sportsview, [football commentator] Kenneth Wolstenholme produced a voting form, pointed to Nat Lofthouse’s name and said: ‘I am putting my cross here.’

“He was showing viewers what to do, but maybe Scots thought he was also indicating who he thought should win. They didn’t like that. They had other ideas.

“But, basically, I was just a young laddie from the Highlands. There was no such thing as celebrity status. When I got back into Aberdeen on the train – I think it was the Flying Scotsman – there was nobody there, except for a cleaning lady. She said: ‘Well done Ian’ and then it was back to school.

“You have got to understand what it was like in those days. Even football wasn’t on TV back then. Bobby Charlton was a £20-a-week footballer.”

Unsurprisingly, Black’s achievements earned him a significant public profile. As somebody still in his teens, the expectation was that his best days lay in front of him. However, after returning to Robert Gordon’s College, he found himself at odds with the head, David Collier, who stripped him of his prefect’s badge and said later he “deplored the fuss” which he claimed gave fellow pupils “the wrong set of values”.

And thereafter, while he was expected to win gold at the Rome Olympics, his preparation was compromised by a lack of access to training facilities in Aberdeen.

Instead, he was forced to endure freezing water at Stonehaven’s outdoor facility and even travelled to Guernsey to use a tidal pool carved out of the coastal rock with his coach Andy Robb; a stark reminder that this was another time, another place from the current situation where participants have access to the Aberdeen Aquatics Centre.

Even while he was still at primary school, the mercurial Black had displayed precocious talent. At the age of nine, he swam from Kessock to Inverness across the Beauly Firth and, at 14, defeated the Scottish butterfly champion.

But his deflating Olympic experience in Italy was the beginning of the end and he quit swimming soon afterwards when he was just 21. He recalled: “I was a very determined competitor and hated losing – that was maybe my strong point.

“Even though I was nowhere near fit enough in Rome, I still thought that I could win. But the other countries were miles ahead of us on training and coaching and I didn’t want to settle for second best.”

After graduating from Aberdeen University, Black followed a career in education and eventually returned to the city as headmaster of RGC Junior School in 1990.

While he was running a swimming class for beginners, he spotted a young pupil with “talent to beat the world” – none other than David Carry, who subsequently surged to a brace of golds at the Commonwealth Games in 2006.

More than 60 years on from his halcyon period, he has never lost his love for the sport and the benefits of healthy exercise. Who knows what else he might have achieved in his career if he had been encouraged to keep making a splash?