There’s something magical about watching a great sports star confronting adversity with the attitude they are not remotely interested in the possibility of defeat.

Heaven knows there have been plenty of depressing aspects to life in the last couple of years, but the ability of somebody such as Rafael Nadal to orchestrate heroics in his realm can lift the gloomiest of spirits.

On several occasions, it seemed as if the Spanish maestro would finally have to yield to the relentless pressure which he had placed on his body for the best part of two decades while he battled injury.

His reputation as one of the greats was already undeniable; a tally of 20 Grand Slam titles testified to the myriad qualities which he brought to tennis since he emerged in the early part of the 21st century.

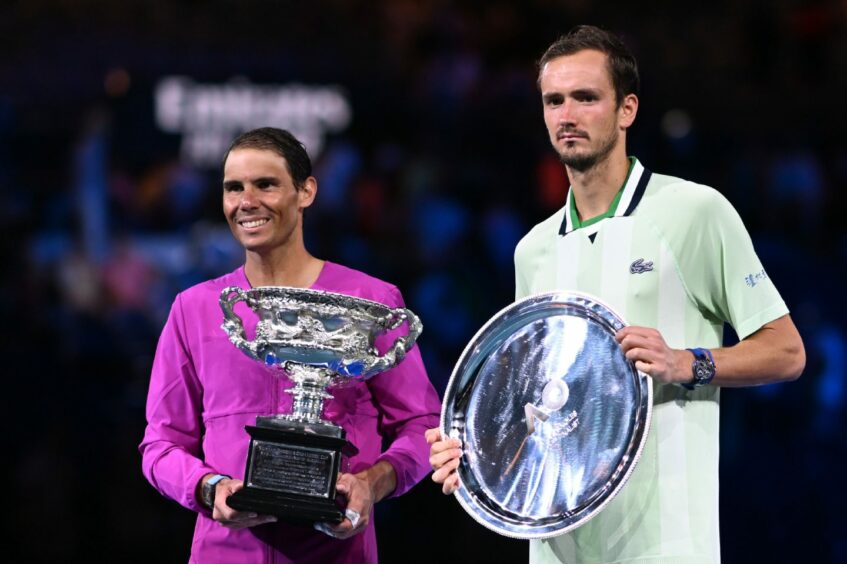

But Nadal has never been content to rest on past glories, or go willingly into the last chapter of his career with a meek surrender. And, as we witnessed during his remarkable performance against Danniil Medvedev in the Australian Open final on Sunday, the scale of his rage can be positively volcanic when he scents he has seized the initiative over any rival.

This was a contest for the ages; a match which lasted nearly five-and-a-half hours, and where Medvedev seemed to have gained an unassailable advantage by winning the first two sets of a fluctuating joust.

Yet, gradually, inexorably, thrillingly, with many glimpses of his reputation as a force of nature, Nadal hunted down his opponent, left him flat-footed and screaming at the crowd in Melbourne, and the tide turned to the point where he could even afford to lose his service game in the climactic set without worrying he may have blown his chance.

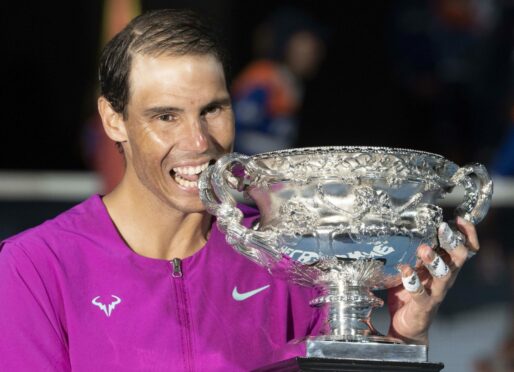

He’s at 21 and on his own

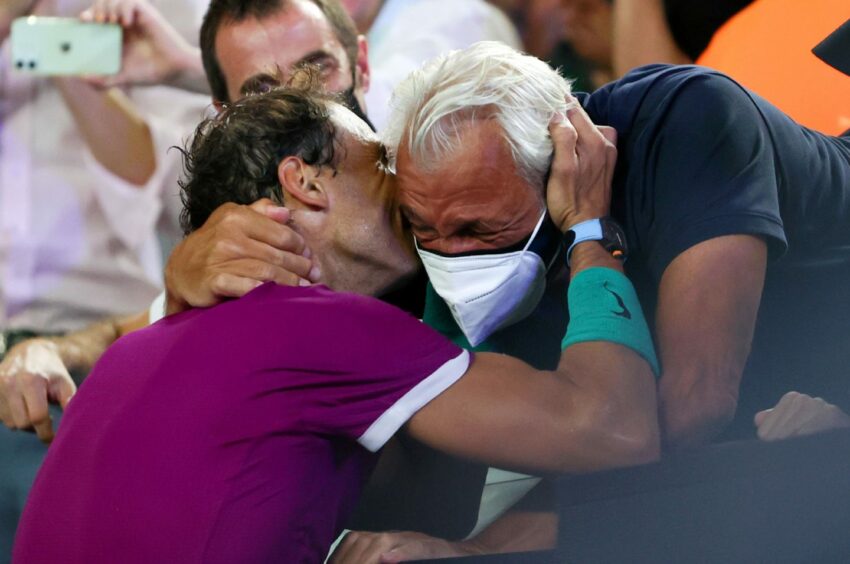

At 35, and having only recently returned to the court after a protracted scrap with injury, it was unsurprising that he slumped into a chair during the post-match speeches from the tournament organisers and sponsors – and the Raging Bull even looked close to falling asleep during the press conferences – but his name is up there again at the summit of the leaderboard with 21 titles.

Indeed, on the evidence of his pyrotechnics Down Under – which contrasted starkly with the increasing controversy over Novak Djokovic’s travel arrangements as the prelude to arriving in Oz in early January – there is no reason why Nadal won’t be the favourite for the French Open in May.

After all, that’s the surface on which he has been almost unbeatable throughout his career. Somebody even joked a couple of years ago that Rafa would win the US election if it was held on clay and the statistics bear out his enduring dominance, given his triumphs at Roland Garros in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020.

He gained the first brace of these Slams as a teenager and I’ve never forgotten the phone ringing at my then home in Falkirk early in 2007 and being wished a good morning from (his uncle) Toni Nadal, who was with his nephew and happy to act as an interpreter while I carried out an interview.

Often enough, these situations are fraught with issues and nuances which are lost in translation. But that was irrelevant here. What immediately became clear was the drive, determination and durability of the youngster.

It was all about work, work, work, about pushing himself harder, expressing himself and doing himself justice at venues such as Wimbledon and Flushing Meadows. Even then, he was in hot pursuit of Roger Federer, and well aware of the threat posed by two other teenagers, Djokovic and Andy Murray.

Control was the secret weapon

Yet, without a sliver of egotism or arrogance, he argued that his priority was to keep improving his own standards rather than worrying about what others might do; something over which he had no control. And, as somebody who has OCD and must bounce the ball a set number of times before any serve, occasionally infuriating opponents and umpires alike, the key was control.

But there was another aspect. As he said: “The glory is in being happy. The glory is not winning here or winning there.

“The glory is in enjoying practising, enjoying every day, enjoying working hard, and always trying to be a better player than before.

“And it is in believing the people who are with you and listening to those who have more experience”.

It’s a straightforward approach, based on the philosophy that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains. Even now, at a juncture where his cv suggests he has nothing left to prove, the fire burns brightly and he is still targeting new milestones and pursuing ambitions.

It would have been very easy for him to capitulate when he was trailing Medvedev, especially after spurning several opportunities in the second set.

Yet, by living in the moment, and erasing the past, Nadal continues to defy the critics who claimed as long ago as 2015 that he was nearing his sell-by date.

Eventually, it’s inevitable that challengers such as Medvedev, Alexander Zverev and Stefanos Tsitsipas will bring about the changing of the guard.

But not yet. Not while Nadal is behaving like Lazarus on an adrenaline rush!